URL = (copy/paste - the blue text - into your Internet browser.

http://voyager-press.com/blog/1942-post-wwii-british-merchant-bono-family-archive-shantung-china/

© by courtesy: Mr. Bernhard Lauser, FRGS (bernie@voyager-press.com)

1942 – Post WWII British Merchant Bono Family Archive – Shantung, China

Posted on April 17, 2019 by admin

Bono Family Archive

Four POWs who Survived Captivity

at Weihsien Concentration Camp

Shantung WWII

Excellent Primary Source Content

Japanese Martial Law

POW Camp Life

Post-War Communist Controlled China

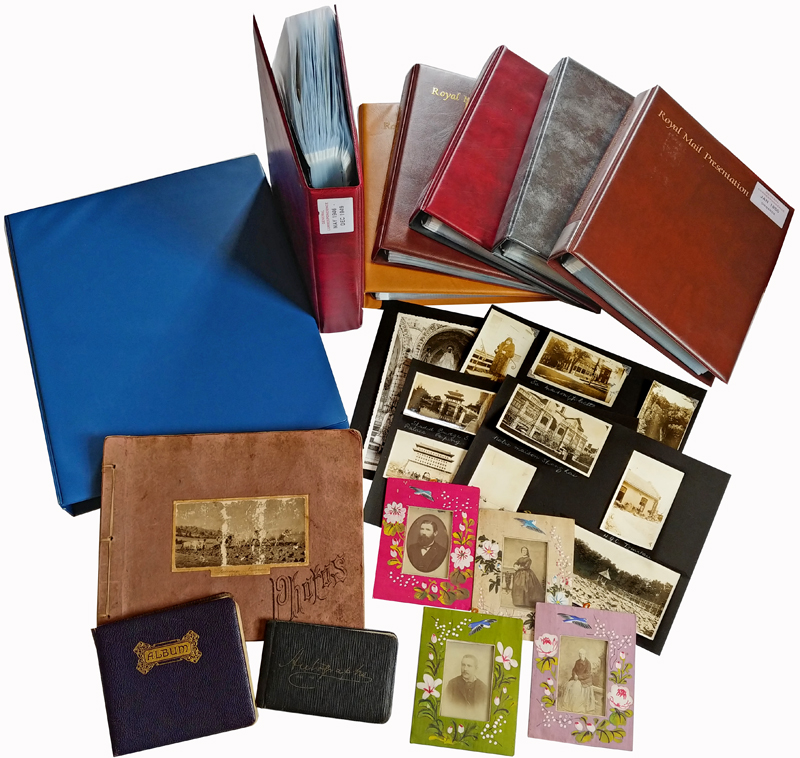

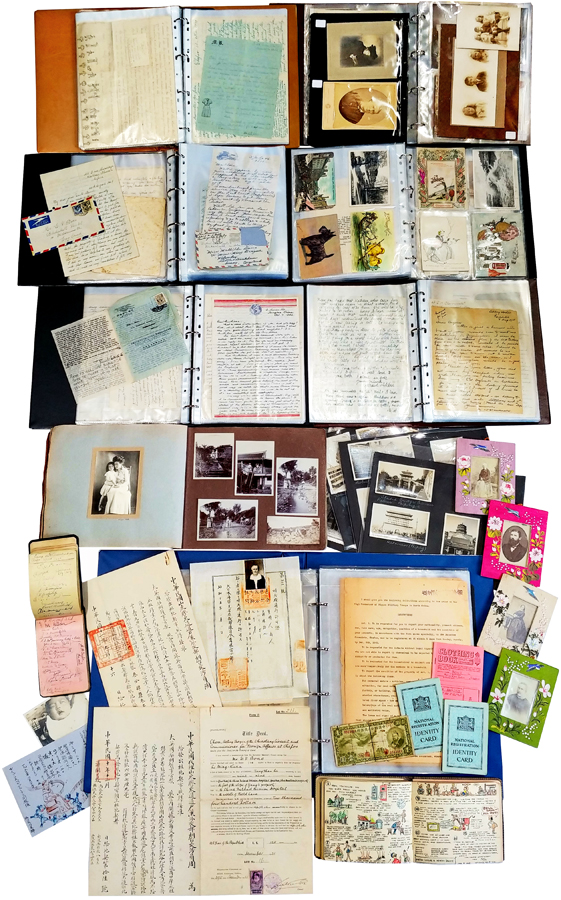

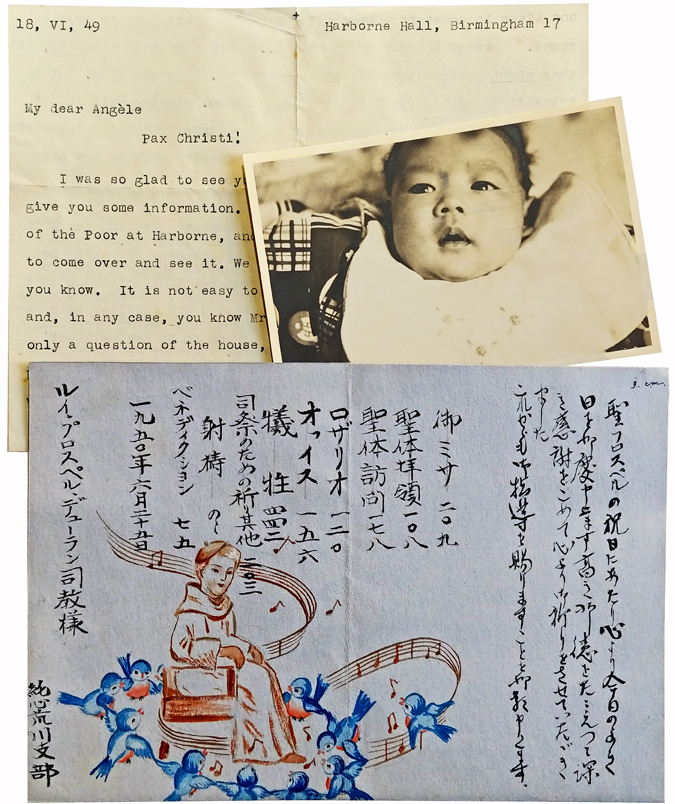

[China], circa 1905-1975. Bono family archive of British merchant Émile Victor Bono, Esq., who served for a number of years as and Chinese Maritime Customs Examiner at Wuhu, and his three children, who were interned with him at the Weihsien [Shantung] POW concentration camp during the second World War, largely tracing the lives of the three siblings, featuring documents concerning their captivity and their lives following the event. Archive consists of some 345 letters mostly in manuscript and some in typescript, 169 photographs approximately half of which are in an album, 2 sketch journals used as album amicorums of sorts and featuring numerous autographs of POWs at Weihsien collected while interned there, several wartime documents detailing the regulations imposed by the Japanese, assorted personalia such as identification, title deeds and details of homes built by the family in China, and some ephemeral items. Text is in French, English, and occasionally Chinese. All items contained and preserved in plastic sleeves house in three-ring binders, with the exception of the photographs. The lot overall in very good condition.

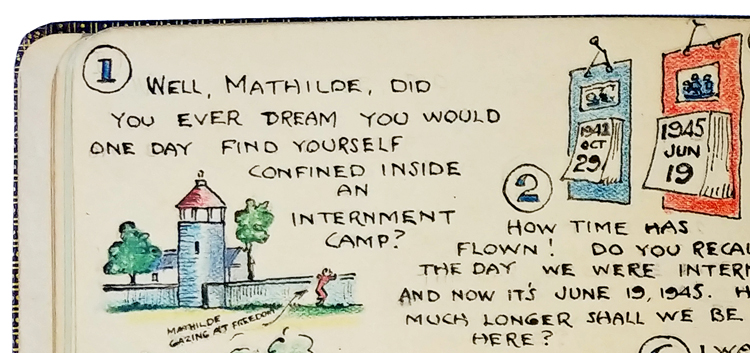

Émile Victor Bono, Esq. (1873-1963) was a merchant, and also a Customs Examiner for the Imperial Maritime Customs at Wuhu, then Chefoo, following in his father’s profession. In 1942 he was taken to the Weihsien Concentration Camp by the Japanese as a POW, along with his three adult children, Albert, Angèle, and Mathilde, all of whom were in captivity there for over 33 months. After long surviving the as a POW in a Japanese internment camp, he died in 1963, in Kidderminster, England.

He was born in China on 8 March 1873 into an affluent family. His father being British Maritime Customs examiner at Kiu Kiang, Charles Victor Bono (1839-1900), and his mother being a Chinese woman, who together had a home, as well as business interests in Kiu Kiang [Jiujiang]. Émile, who preferred to go by his middle name Victor, had a special liking for the tranquility of inland Kiu Kiang, where he likely spent part of his childhood years, and returned often in his adult life. He was in Amoy in 1896, by this time engaged to a French woman in Paris named Léontine Emilie Viau (born circa 1869/70, died 1942). By December 1901 he was settled and working in Wuhu. After much detailed planning, Léontine arrived in China in October 1902. For her first few years in the Far East, until around 1905, she stayed near “Victor’s” mother in Kiu Kiang. Finally, “Victor” and his wife were settled in Wuhu by 1906, and in Chefoo after that.

E.V. Bono and family were captured as POWs on 29 October 1942 and held captivity at the Weihsien concentration camp [Shantung]. According to documents in the present archive, by October 1944 Mr. Bono had been assigned the job of ‘warden’ in the internment camp. An application for Red Cross Supplies found herein and dated 12 February 1945 states that he was then 71 years of age. The Bono family’s internment, as well as the hundreds of other POWs, lasted until 17 August 1945, when American paratroopers liberated the camp. Their time in captivity had been 33 and a half months.

Mr. Bono’s wife Léontine died before he and their children were taken as POWs. The final mention of her being alive, in the present papers, is on an assessment document produced for the Japanese invaders, dated 3 January 1942 at Chefoo. In this, she is described as “an invalid, bed-ridden… requiring a special diet… Doctor’s occasional attendance and medicines, with resultant expenses.” Léontine died of her illness, in their Chefoo home, in the coming months on 7 October 1942, only three weeks before her husband and children were taken captive by the Japanese on 29 October 1942.

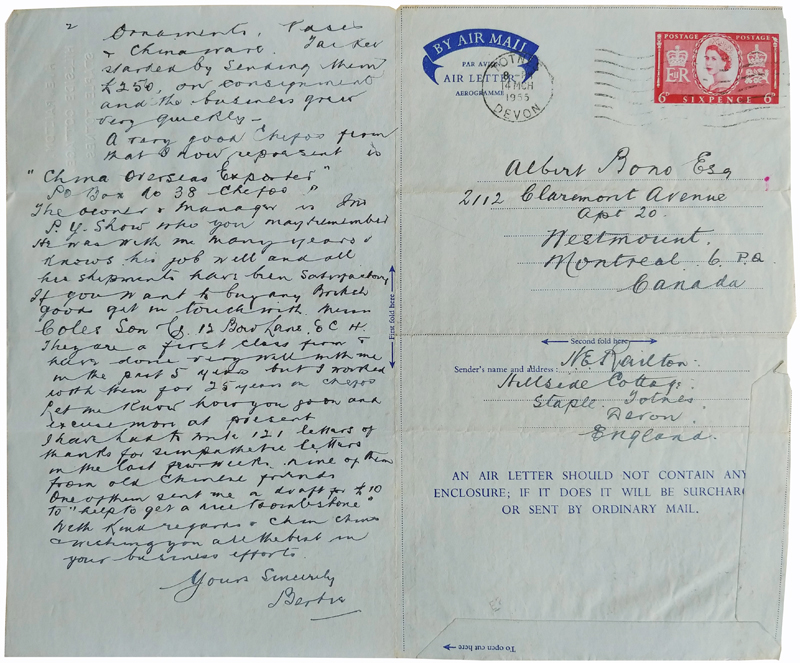

Albert was a merchant in China, settled in Canada sometime after the war, and later pursued matters of compensation from the family’s sufferings under Japanese occupation, and as POWs. Angèle pursued a career in the medical field, possibly as a nurse, and in 1954 accepted a post offered to her by the Ministry of Health, for employment at Wolverley Camp, 2 miles north of her home at Kidderminster. Mathilde, too, was employed at Wolverley Camp.

The Weihsien concentration camp, also known as the Weixian Internment Camp [Shantung], situated in the coastal city of present-day Weifang, Shandong province, was the largest World War II Japanese camp in China. It held 2,008 people from more than 30 countries, 327 of these prisoners being children. Most of the internees endured three years there.

In 1941, Japanese invaded China. Foreigners were forced to wear armbands identifying their nationality, to observe curfews, etc. Internment camps were quickly established, and within a year, all Allied Westerners in Japanese-occupied China were interned in camps.

The Weihsien camp was under full military management; the walls were covered with electrified wires; the guard towers were equipped with searchlights and machine guns. Families lived in small rooms with no sanitary facilities. Living quarters were very cold most of the year. Internees were counted by the Japanese three times daily. Children worked, even the young ones performing menial tasks. Due to horribly unsanitary conditions, shortages of food and lack of medical care, several people died in the camp.

Local Chinese peasants became heroes; farmers risked their lives to smuggle food over the wall to prisoners, creating the so-called ‘black market.’ Others took many risks to help internees deliver important messages, and also helped Arthur W. Hummel (called Heng Anshi in Chinese) to escape. Those who were caught were beaten and tortured. Even after the war, some locals continued to bring food so generously to those who had been displaced and lost everything.

The Japanese army was losing ground in most of China in 1945 and victory was almost assured, but the news was blocked. It wasn’t until the US rescue planes hovered over Weihsien camp and massive parachutes drifted slowly to the ground, that the internees knew that captivity was no more. On August 17, 1945, the Duck Mission Team, comprised of these six men and a young Chinese interpreter jumped out of a B-24 aptly named “The Armored Angel” to liberate some 1,500 Allied civilian prisoners. The latter poured to the gate to welcome the heroes, and their own freedom, at long last.

Today, at a nearby location, a public square houses a 20-meter memorial sculpture that depicts a group of foreigners holding hands with Chinese people. The base of this monument is covered by carved Chinese characters that spell the names, ages, professions and nationalities of 2,008 internees.

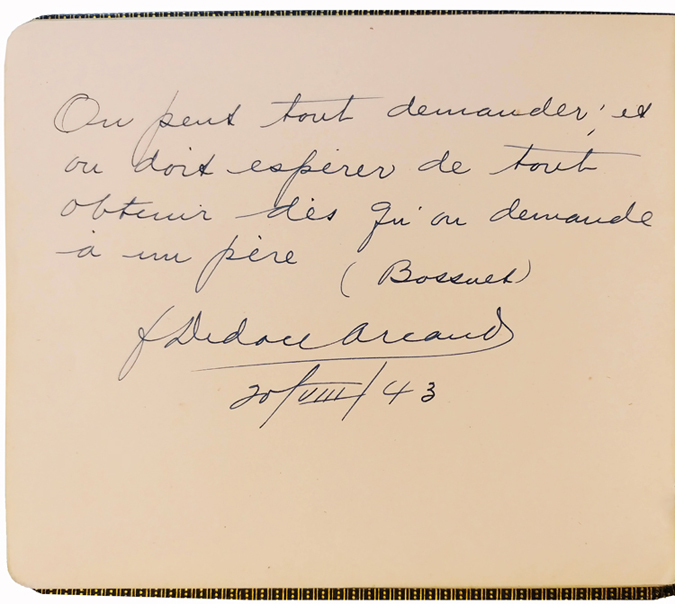

The prisoners’ names include renowned politicians, artists, scientists and even sportsmen, including Raymond Jaegher – a foreign-born adviser to Chiang Kai-shek; Father Didace Arcand who would be martyred by his ill-treament during captivity by the Chinese Communists a few years later; the Reverend W.M. Hayes – president of the former Huabei Theological Seminary; Arthur W. Hummel, former US ambassador to China; and British athlete Eric Liddell who won the 400m gold medal at the 1924 Olympic Games.

A thorough list of Weihsien POW captives is available on this website:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/RonBridge/habitants/weihsien02.pdf

E. Bono named is on the list of ‘inhabitants’ at the Weihsien POW camp, as are his son Albert J. Bono (born 13 November 1906), his daughter Angèle (born 18 April 1910), and his daughter Mathilde (born 26 February 1913). His wife Léontine is not named on the list as she had died ten months prior to their captivity.

Also found online, “The Report of Real Estate”, registered to Japanese military authorities on 5 January 1942, states that he was a retired merchant, age 68, his residential address being No.7, Field Lane, Chefoo.

Following are some highlights from the archive:

Documents and personalia concerning Japanese occupation in China and the Bono family’s captivity as prisoners of war, held at the Weihsien concentration camp for over 33 months:

⚈ Notification Order [First week of January 1941], requiring foreigners to wear a distinguishing band on their left coat sleeve. [In 1941, under Japanese occupation, foreigners were required to wear armbands identifying their nationality, and to observe curfews. A year later, internment camps were established and filled.]

⚈ Small manuscript notice of a motorcar being confiscated by Japanese military for their use

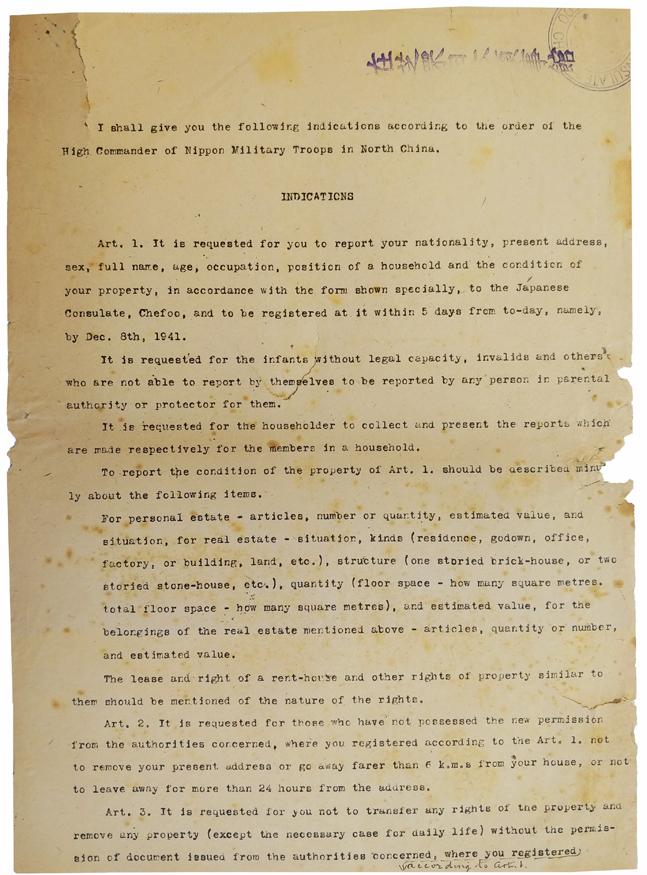

⚈ A proclamation issued on 8 December 1941 by the "High Commanders of Nippon Military and Navy Forces in North China", ordering that all British and American subjects to register with the Japanese government, and to further report their property and assets in China which required an itemized list of every possession including articles of clothing and every household minutiae

⚈ A proclamation issued on 10 December 1941 by the Japanese Consulate requiring all American and British people to provide a detailed list of all property movable and immovable, together with Mr. Bono’s fastidiously detailed inventory of personal belongings including his private residence, offices leased, and all contents within, each list with monetary estimations as required.

⚈ Manuscript translation in English, of Martial Orders declared 21 December 1941, being “Japanese instructions for foreigners”, eg. wearing an armlet at all times for “protection and control”, minors to further carry a passport at all times.

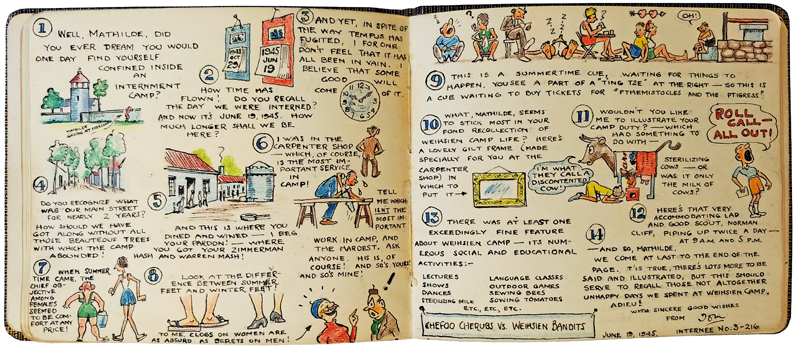

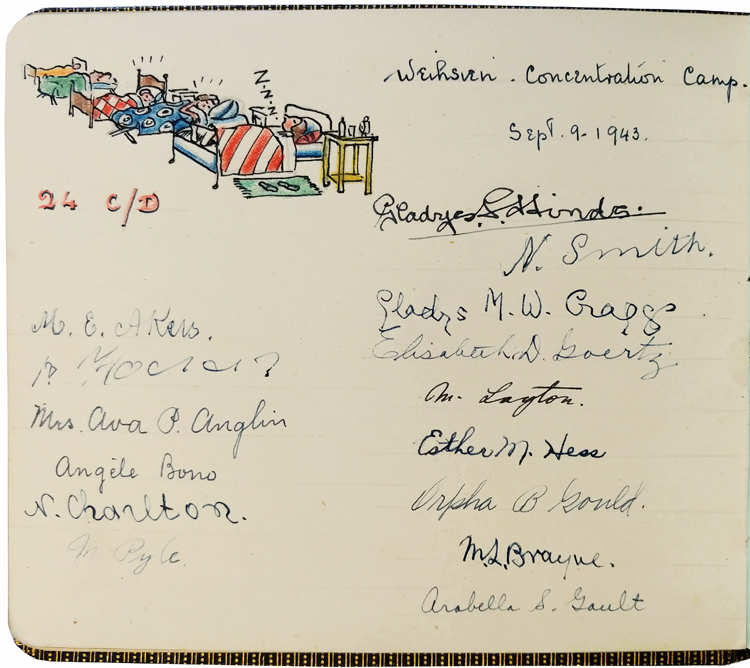

⚈ Two sketch journals which contain manuscript passages, darwings and autographs, made by several POWs at captives at the Camp during their captivity, including manuscript drawings, and one remarkable double-page illustrated caricature chronicle of the 33 months made by a fellow internee. Several internees have signed these volumes including the now famed martyr Father Didace Arcand.

⚈ A notice from the British Section of the Chefoo Mutual and Committee, 26 March 1942, providing instructions for applications from anyone desiring repatriation.

⚈ Typescript correspondence between Mr. Bono and the Japanese Army Discipline Office, concerning accusations of over-stocking coal dust within his ward.

⚈ A typescript copy from a firsthand account, humourously describing a scene at kitchen No. 2 at the Weihsien POW Camp.

⚈ 1947 papers concerning a POW Claim filed against the Japanese for losses and damages from the war

⚈ Post war claims including a register of loss or damage submitted circa 1947 by Mr. Bono, and a later enquiry into war compensation for POWs in the form of a letter written in 1954 by his son Albert J. Bono.

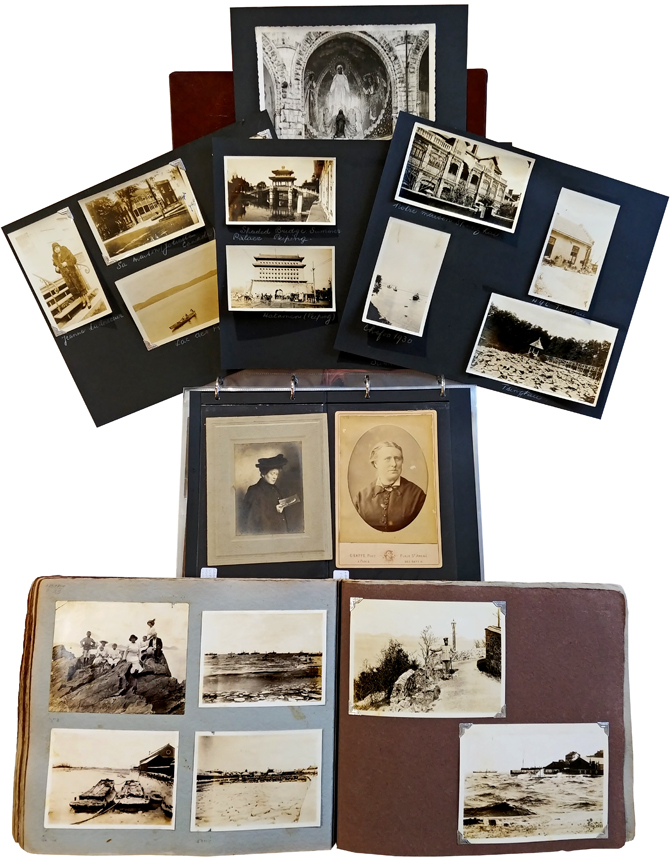

Family Photographs Spanning Multiple Decades

⚈ An early family album with numerous photographs taken in Chefoo, featuring Mr. Bono, his wife Léontine, and their young children. There is another child, Shai, born circa November 1905 and possibly the daughter of a servant. A few scenes capture family sojourns and what appears to be scenes from Mr. Bono’s work at various ports as Imperial Maritime Customs Agent. Altogether 86 photographs; sizes vary.>

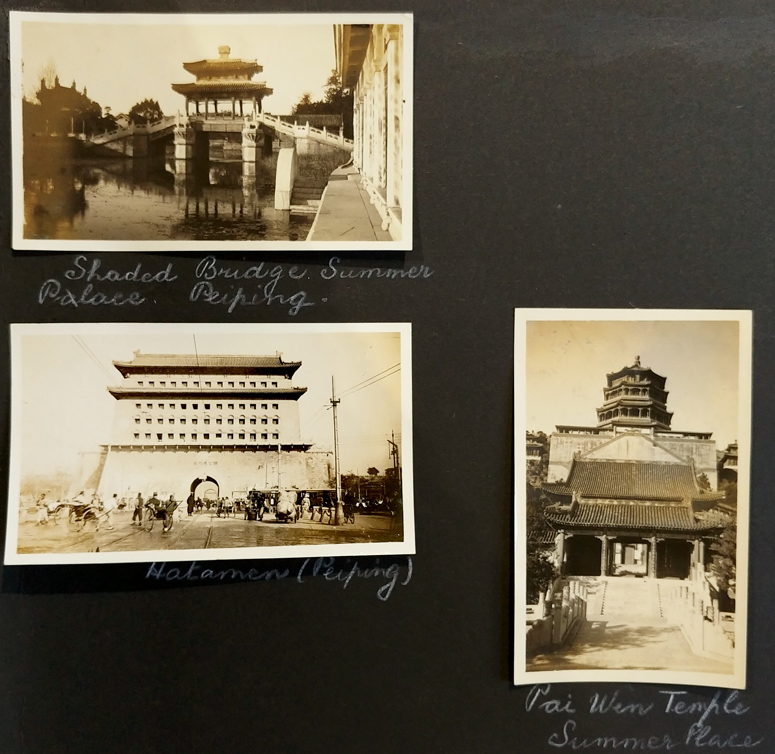

⚈ Snapshot images including the Zhengyangmen gate at Peiping, the Summer Palace bridge at Beijing, a park lake at Tsingtao, a magnificent home in Shanghai, and the Chefoo harbour, this lot numbering 7 photographs mounted to two black cardstock leafs.>

⚈ Portraits, carte-de-visite photographs, and more snapshot scenes of family and friends, spanning several generations, including Léontine’s mother, Léontine as a child, Emile Victor Bono in his aged years, sisters Angèle and Mathilde in their later adult years back in England, and even Albert’s yacht “Fleur Chinois,” these all of different formats and sizes, 72 in number.>

⚈ 4 portrait carte-de-visite photographs produced in France, presumably of Léontine’s family, each framed in a hand painted Chinese silk frame with cardstock backing, protective glass cover over image, and small string for hanging. Each frame measures approximately 11,5 x 15 cm, in very good, original condition.>

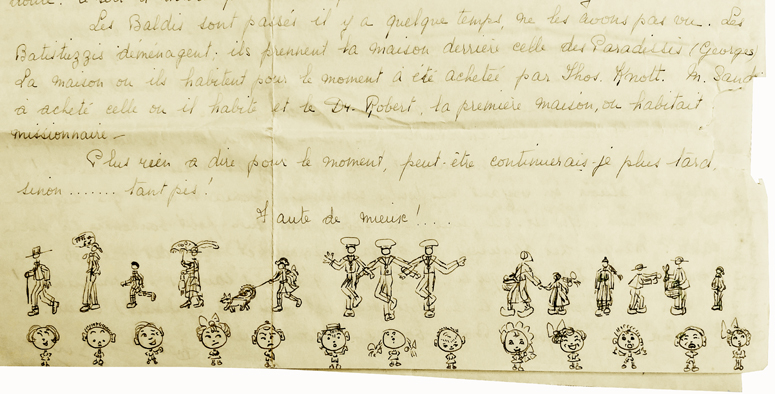

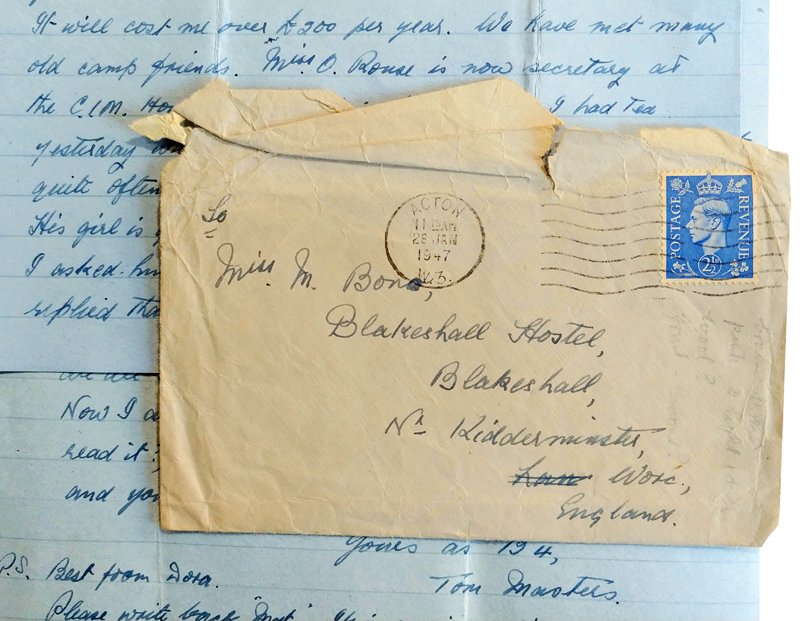

A voluminous archive of correspondence, which essentially traces the lives of Mr. Bono’s three children, who were interned at the same POW camp as he had been during the Second World War. The letters begin with several letters penned at Chefoo by Léontine Bono addressed to her daughters Angèle and Mathilde from 1930-32, which reveal much about their personal lives in China prior to invasion and captivity by the Japanese. Correspondence amongst family, including extended family, resumes after the war. Especially interesting are the many letters to Mathilde and Angèle from friends in China from 1946 to 1949, who frequently discuss the state of affairs there after the war, as well as the whereabouts of some who were fellow internees at Weihshien Camp. This includes a letter to Mathilde from Tom Masters, possibly the former POW who drew the caricature chronicle in her album amicorum, whose letter of 26 January 1947 explains that he had recently left China to return home to London. Some in English and some in French.

A few excerpts from the post-war letters to Mathilde and Angèle:

Letter from Tsingtao 9 May 1946. “… about your former home Chuyung Kwan No. 9 I am afraid it wouldn’t seem very much like home to you now… it is being taken over by a Chinese… coming and going inspecting the rooms, taking a list of all the furniture… It seems that they are going to turn the place into s boarding house.”

Letter from Tientsin [Tianjin] 31 October 1946. “… right at this moment the Nationalists are trying to take Chefoo from the Communists… Chefoo has taken an awful beating and it isn’t the place it used to be… but there is one thing here – we have no rationing, and if you have the money you can buy anything…lots of ways to make money and the honest way is the hard way… quite a number who made a pile during the war has had that pile taken away by the present powers… thrown in jail… Chinese jail is something to remember for a long time if you can get out alive… the Communists are quite active near Tientsin… they have 2 American marines and 1 Italian as prisoners…”

Letter from Tsingtao, Holy Ghost Convent, 8 April 1947. “… our sisters have had to leave the convent and are all here like the Novices ‘in refuge.’ The railway between here and Tsinan is ruined again and the Reds are rampant all over the place…”

Letter from a fellow POW, writing from 12 Hunan Road [Nanjing?], 9 January 1948. “… I have kept all those poems you wrote to me while at the Red Cross… After camp life, I had enough of lining up and wearing cast offs. At least now if one has money, it is possible to get something new without coupons.”

Letter from a fellow POW (same as above), writing from 12 Hunan Road [Nanjing?], 6 March 1948. “…Quite a lot of excitement prevails here at present over the idea of being able to return to Chefoo… the Chinese General of the 8th Army, General Li Mi, had said… that he could not understand why the old residents of the port had not long ago returned to repair their houses and resume business… Our Chinese friends in Chefoo say not to be in a hurry yet to return and that we had better remain in Tsingtao… Since receiving this advice we have learned that both sea-ports of Longkow and Weihaiwie are again in Communist hands and are pressing nearer to the outskirts of Chefoo. General Li Mi passed through here two days ago en-route to Nanking: rumour has it to confer with Chang-kai-shiek on the possible evacuation of Chefoo by the Nationalists.”

Letter from Tientsin [Tianjin] 6 February 1948. “Tientsin and the rest of China is really getting from bad to worse… supposedly clearing the Palus from the Shantung Peninsula, but now fighting is breaking out there again. Weihaiwei is surrounded. The situation in Manchuria is pretty bad, but the Nationalists swear they won’t give it up… The Palus are always just outside the city limits, and we have had curfew from 11.30 to 6 am… No more dancing… no more hunting… We certainly are working under tremendous handicaps here… Kowloon and Shameen riots… student riots in Shanghai… Chefoo is still in the Nationalists hands… seems all foreigners have left. The Palus are pretty rough on Missionaries…”

Letter from Tientsin [Tianjin] 22 March 1949 – a firsthand account of the Tianjin Campaign

“… Before the trouble started we had a meeting of all the British Residents when it was decided to evacuate any non-essentials who were willing to leave. Most of the big firms evacuated the families of employees with contracts. The rest decided to remain to save their businesses… we who stayed in Tientsin are all safe though we have passed through some rough time, the situation got bad when Fu Tao Yi decided to evacuate Tongshan – the coal center – Chingwantao the Port was evacuated & looted by the Nationalists. Then at the beginning of the year, Tientsin was under siege… fighting in the suburbs… machine guns & heavier heavier stuff all through the night… plate glass show windows were smashed… one shell hit our neighbour’s chimney & exploded in our yard… the next morning the Palus came in & in their word ‘Liberated the town?’… plenty of resistance in places… lots of loose ammo lying about… hand grenades & land mines… Sunday was a day of rejoicing… ‘Down with American Imperialism – Capture Chiangkai Shek alive – Long Live Mao Tze Tung’… The Palus immediately took control… changed the currency… they control practically everything… All the Jews in Tientsin are leaving for Palestine…”

End Excerpts.

Family Documents, Personalia, Ephemera

• Birth certificates of his daughter born in Chefoo, 1910

• Emile Victor Bono’s National Registration Identity Card and Medical Card

• Angèle’s Bono’s National Registration Identity Card

• Two title deeds for land leased at Chefoo in December 1922, English and Chinese text, completed and signed in manuscript

• Building plans and all related papers for a home constructed at in 1931

• Detailed plans and receipt for a summer house constructed in 1934

• Two passports stamped and numbered, made in China circa 1940-42, each with photograph affixed to recto, one for Mrs. Léontine Bono, the other for her son Albert.

• Angèle’s small sketch journal / album amicorum, with entries made by herself and many friends from 1920s-70s (mentioned above in the captivity related documents)

• Mathilde’s sketch journal / album amicorum, with entries dating circa 1928-1965 (mentioned above in the captivity related documents)

• Angèle’s manuscript account of her post war voyage from Tsingtao to England, via Colombo, the Suez Canal, and Port Said, having departed on 25 March 1946 and arriving in May.

• Correspondence concerning misdirected luggage of both Emile Victor Bono and his daughter Miss Mathilde Bono, during their journey from China to England in 1946. The luggage was mistakenly sent to Belgium, finally located and returned one year later.

• A Chinese 1 Yuan paper currency note printed in 1938. Issued by the Japanese Puppet Provisional Government of North China in Peking (Beijing, Pekin) led by Wang Kemin (Chairman of North China Political Council): Federal Reserve Bank of China. Front featuring the portrait of Confucius (551-479 BC, Kong Fuzi, Kong Qiu, Kongzi; Lao Tzu, Laotse, Lao-Tze, Lao-tsu), Chinese philosopher, founder of Taoism, as well as a mythical legendary Chinese dragon, steamship and junks at sea. Verso features the Liao dynasty XIIth century 13 story pagoda tower known today as the Temple of Heavenly Peace (Tianningsi) and is the oldest standing building in Beijing. Material: Mitsubishi paper made from Manila kemp and kraft pulp.

• Emile Victor Bono’s personal Clothing Ration Book with most tokens unclaimed. [During the war it became difficult to import cloth from abroad and British clothing manufacturers had to use what material they could get to make parachutes and uniforms for the Armed Forces rather than civilian clothing. As a result, clothes had to be rationed from June 1941 onwards. Every man, woman and child in Britain was issued with a ration book containing magenta, olive and crimson coupons. In 1941 each person was allowed a maximum of 66 coupons per year, which was equivalent to one complete outfit. Clothes rationing continued until 1949, and food rationing until 1952.

The Imperial Maritime Customs dates back to June 1854, when the Chinese authorities accepted a need for a foreign Inspectorate of Customs to oversee the operations of the Chinese Customs Houses in Shanghai. This need was partly driven by the rampant smuggling and corruption resulting from China’s increasing trade and commerce, and partly to ensure that all the tariff revenues were collected consistently at the trade ports.

Wuhu became a treaty port in 1877. Most of the core area alongside the Yangtze River was ceded in the British concession. Trade in rice, wood, and tea flourished at Wuhu until the Warlord Era of the 1920s and 1930s, when bandits were active in the area. At the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War, part of the Second World War, Wuhu was occupied by Japan on 10 December 1937. This was a prelude to the Battle of Nanjing, ending in the Nanjing Massacre.