LIFE magazine

December 1943 ...

The Japanese ship "Teia Maru" (ex- s/s ARAMIS of the French: Messageries Maritimes) moored at Mormugao for the civilian exchange operations. The s/s GRIPSHOLM can be seen in the background, just behind the harbour's cranes.

The s/s GRIPSHOLM, a few months later ...

... from Don Menzi's scrapbooks:

AMERICANS' RETURN

LIFE'S TEAM BRINGS STORY OF REPATRIATE HOMECOMING

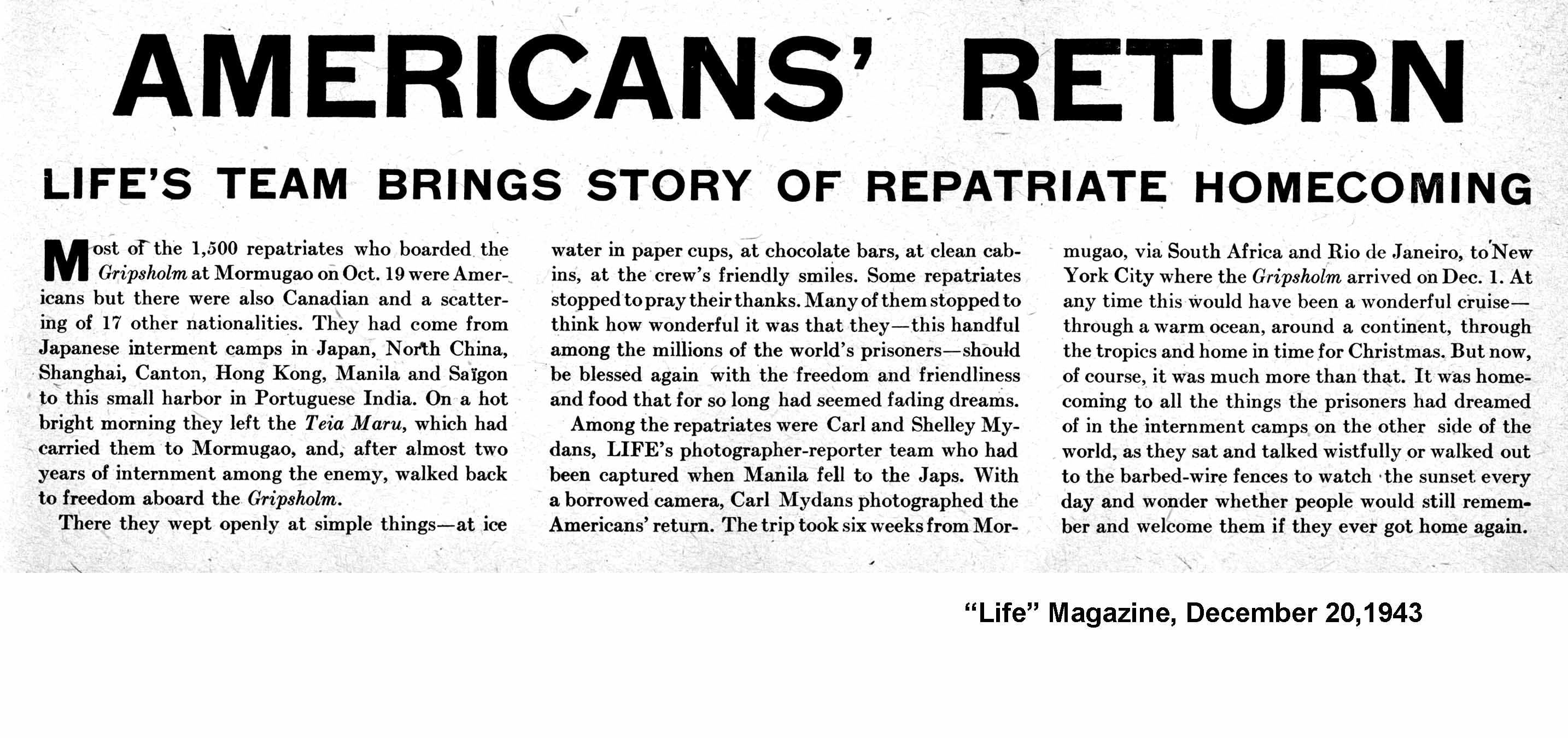

Most or the 1,300 repatriates who boarded the Gripsholm at Mormugao on Oct. 19 were Americans but there were also Canadian and a scattering of 17 other nationalities. They had come from Japanese internment camps in Japan, North China, Shanghai, Canton, Hong Kong, Manila and Saigon to this small harbor in Portuguese India. On a hot bright morning they left the Teia Maru, which had carried them to Mormugao, and, after almost two years of internment among the enemy, walked back to freedom aboard the Gripsholm.

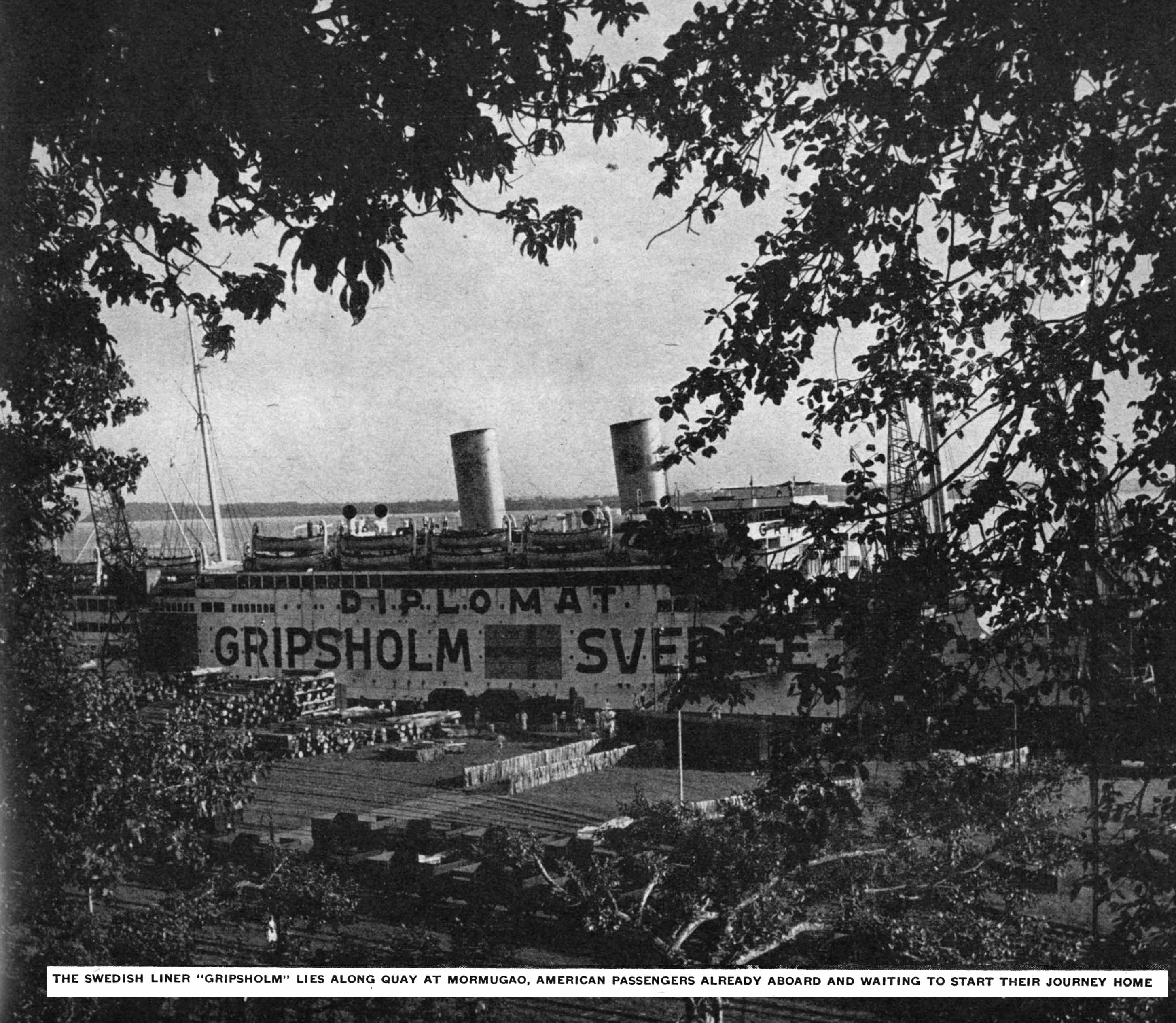

There they wept openly at simple things—at ice water in paper cups, at chocolate bars, at clean cabins, at the crew's friendly smiles. Some repatriates stopped to pray their thanks. Many of them stopped to think how wonderful it was that they—this handful among the millions of the world's prisoners—should be blessed again with the freedom and friendliness and food that for so long had seemed fading dreams.

Among the repatriates were Carl and Shelley Mydans, LIFE's photographer-reporter team who had been captured when Manila fell to the Japs. With a borrowed camera, Carl Mydans photographed the Americans' return. The trip took six weeks from Mormugao, via South Africa and Rio de Janeiro, to New York City where the Gripsholm arrived on Dec. 1. At any time this would have been a wonderful cruise—through a warm ocean, around a continent, through the tropics and home in time for Christmas. But now, of course, it was much more than that. It was a homecoming to all the things the prisoners had dreamed of in the internment camps on the other side of the world, as they sat and talked wistfully or walked out to the barbed-wire fences to watch the sunset every day and wonder whether people would still remember and welcome them if they ever got home again.

"Life" Magazine, December 20, 1943

The Swedish Liner "GRIPSHOLM" lies along quay at MORMUGAO, Americam passengers already aboard and waiting to start their journey home.

THE FIRST MEAL on the Gripsholm had everything that the repatriates used to dream of in the internment camps. There was white bread, butter, tomato juice, cold ham and roast beef, turkey, potato salad, vegetable salad, hard-boiled eggs, cheese, cucumbers, pickles, olives, fruit salad, iced tea with lemon. The people cheered as the stewards set out each new dish. They ate warily, mindful of the dangers of overeating. And they laughed all the time so that they wouldn't cry.

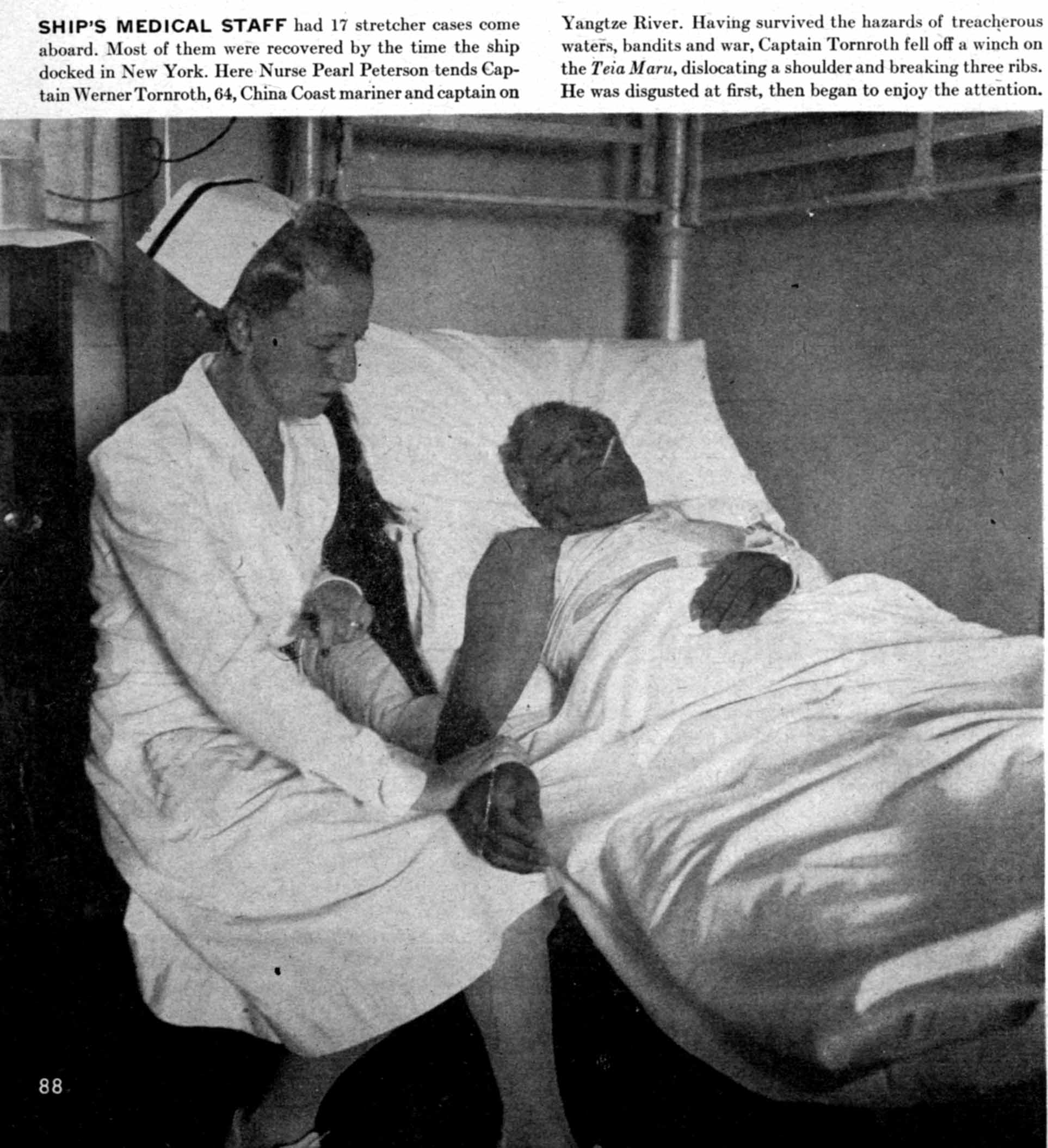

SHIP'S MEDICAL STAFF had 17 stretcher cases come aboard. Most of them were recovered by the time the ship docked in New York. Here Nurse Pearl Peterson tends Captain Werner Tornroth, 64, China Coast mariner and captain on Yangtze River. Having survived the hazards of treacherous waters, bandits and war, Captain Tornroth fell off a winch on the Teia Maru, dislocating a shoulder and breaking three ribs. He was disgusted at first, and then began to enjoy the attention.

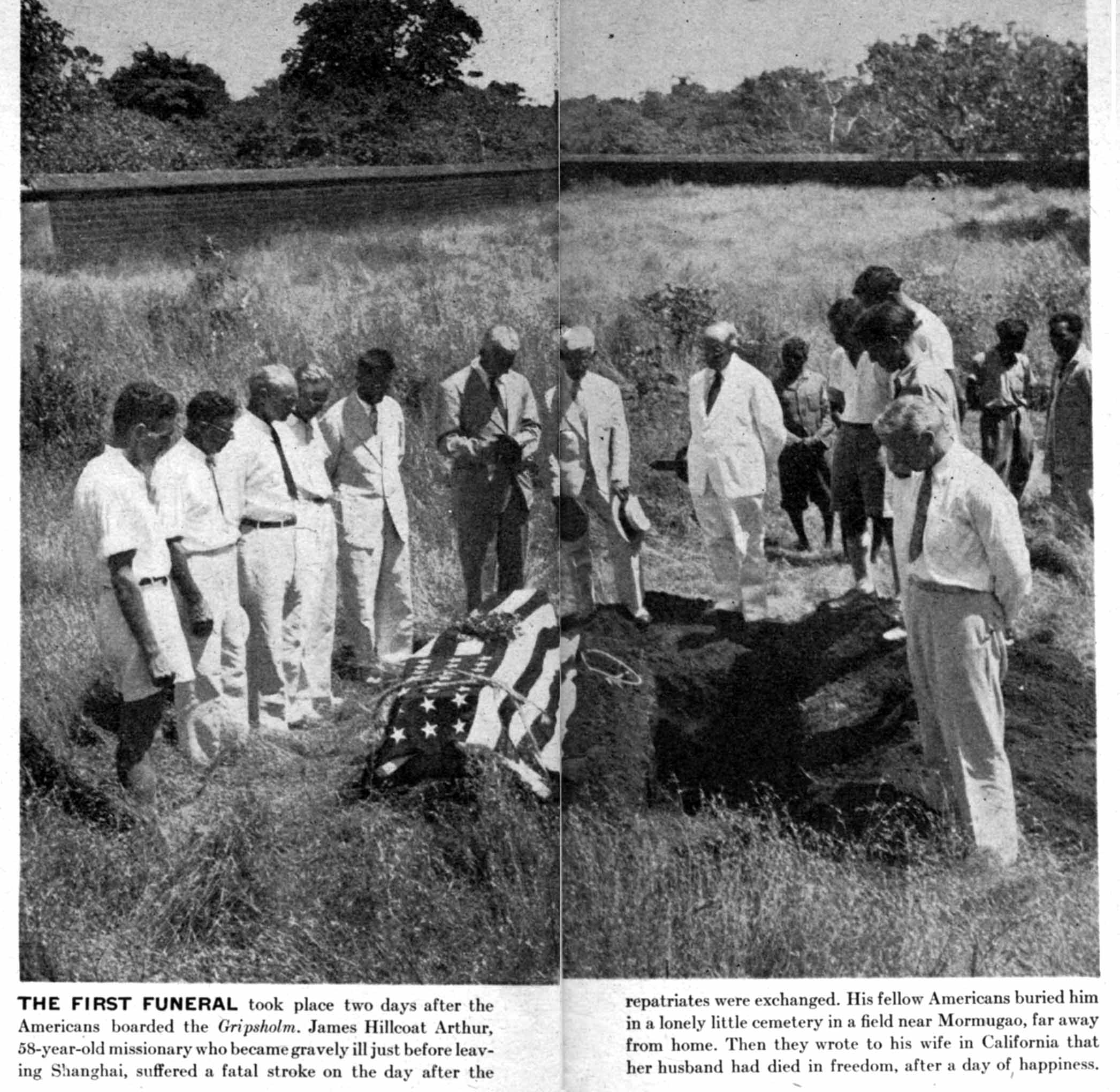

THE FIRST FUNERAL took place two days after the American boarded the Gripsholm. James Hillcoat Arthur, 58-year-old missionary who became gravely ill just before leaving Shanghai, suffered a fatal stroke on the day after the repatriates were exchanged. His fellow Americans buried him in a lonely lilt le cemetery in a field near Mormugao, far away from home. Then they wrote to his wife in California that her husband had died in freedom, after a day of happiness.

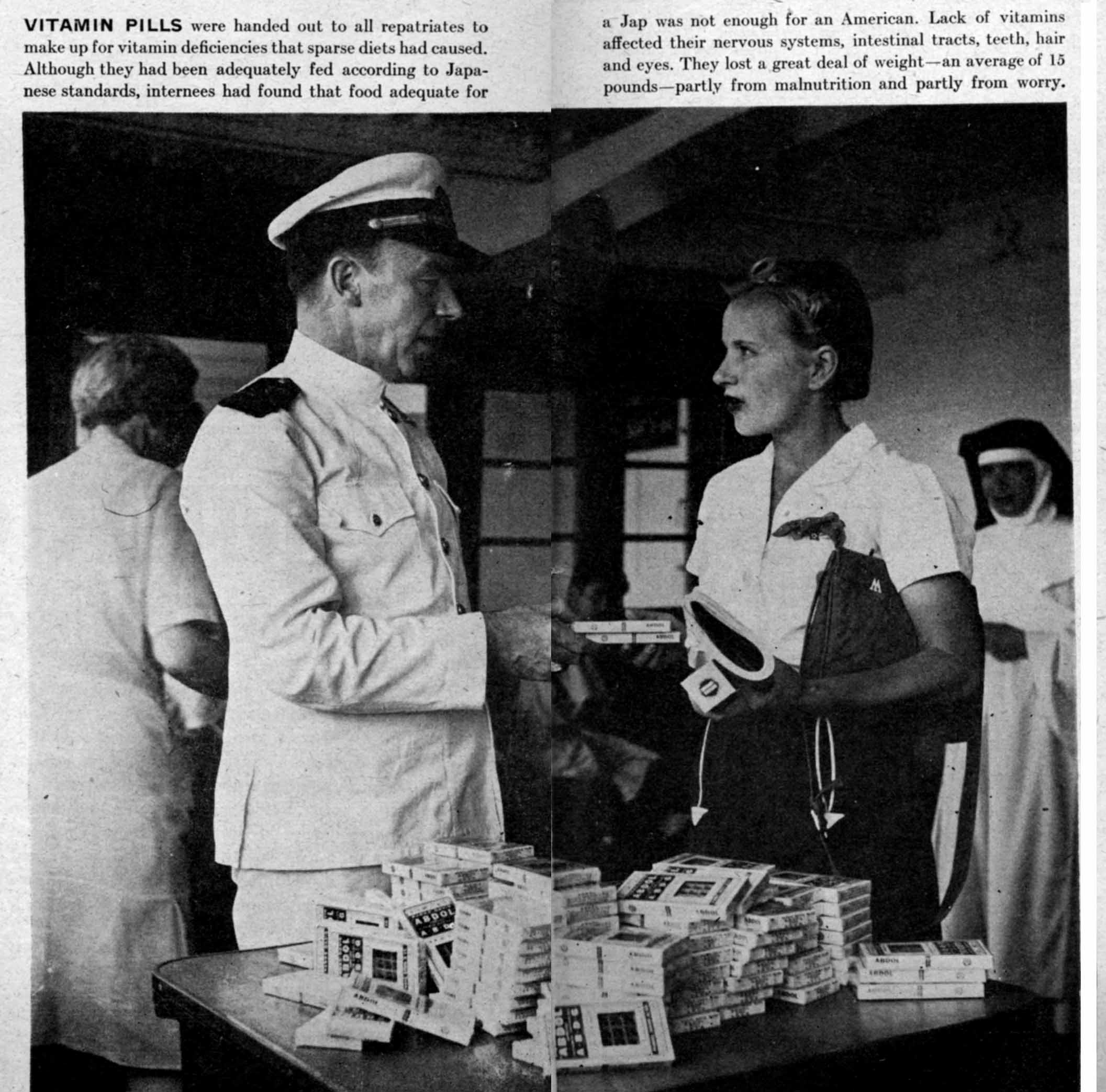

VITAMIN PILLS were handed out to all repatriates to make up for vitamin deficiencies that sparse diets had caused. Although they had been adequately fed according to Japanese standards, internees had found that food adequate for a Jap was not enough for an American. Lack of vitamins affected their nervous systems, intestinal tracts, teeth, hair and eyes. They lost a great deal of weight—an average of 13 pounds—partly from malnutrition and partly from worry.

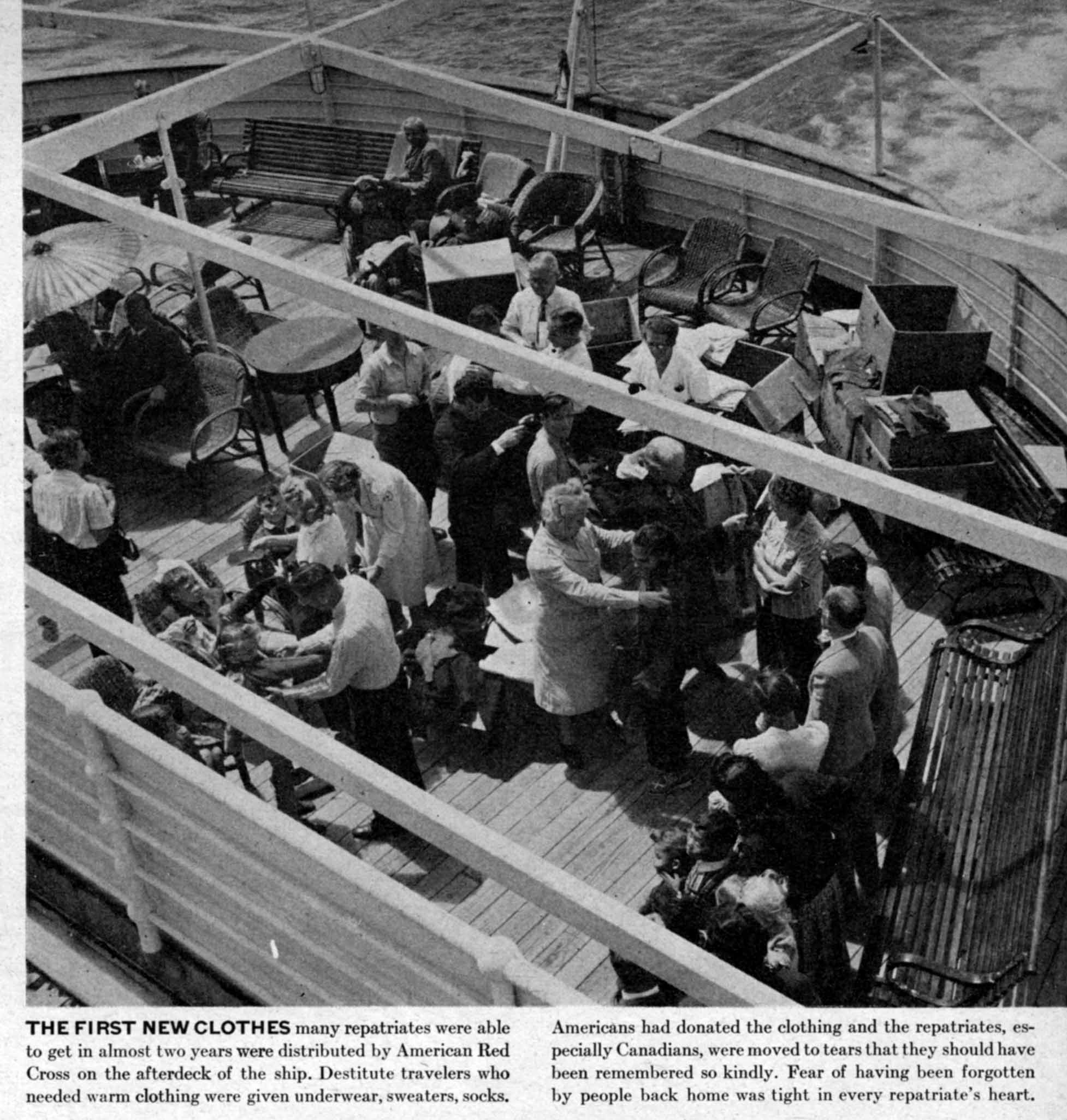

THE FIRST NEW CLOTHES many repatriates were able to get in almost two years were distributed by American Red Cross on the afterdeck of the ship. Destitute travelers who needed warm clothing were given underwear, sweaters, and socks.

Americans had donated the clothing and the repatriates, especially Canadians, were moved to tears that they should have been remembered so kindly. Fear of having been forgotten by people hack home was tight in every repatriate's heart.

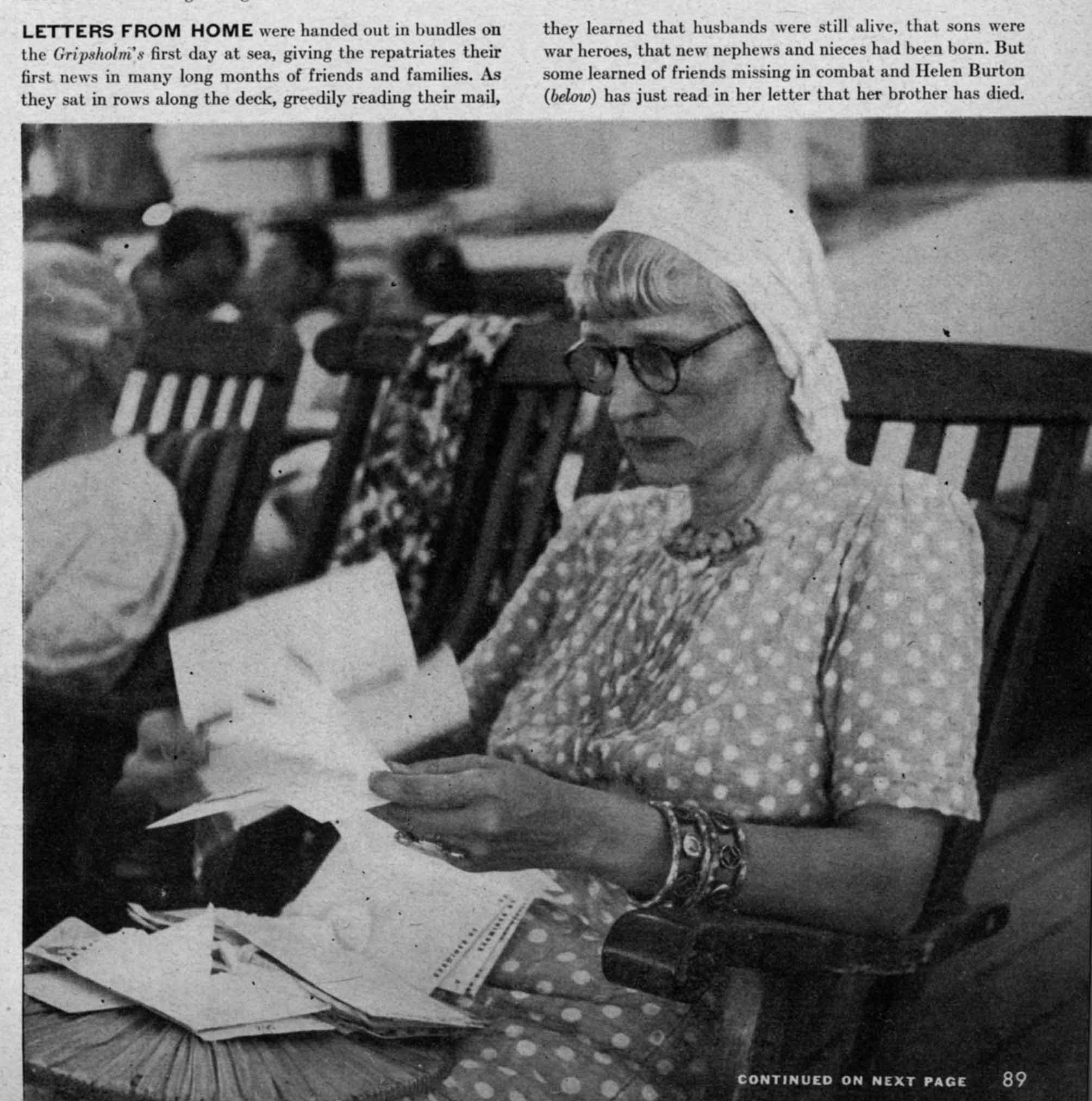

LETTERS FROM HOME were handed out in bundles on the Gripsholm's first day at sea, giving the repatriates their first news in many long months of friends and families. As they sat in rows along the deck, greedily reading their mail, they learned that husbands were still alive, that sons were war heroes, that new nephews and nieces had been born. But some learned of friends missing in combat and Helen Burton (above) has just read in her letter that her brother has died.

THEY WERE A VARIED GROUP

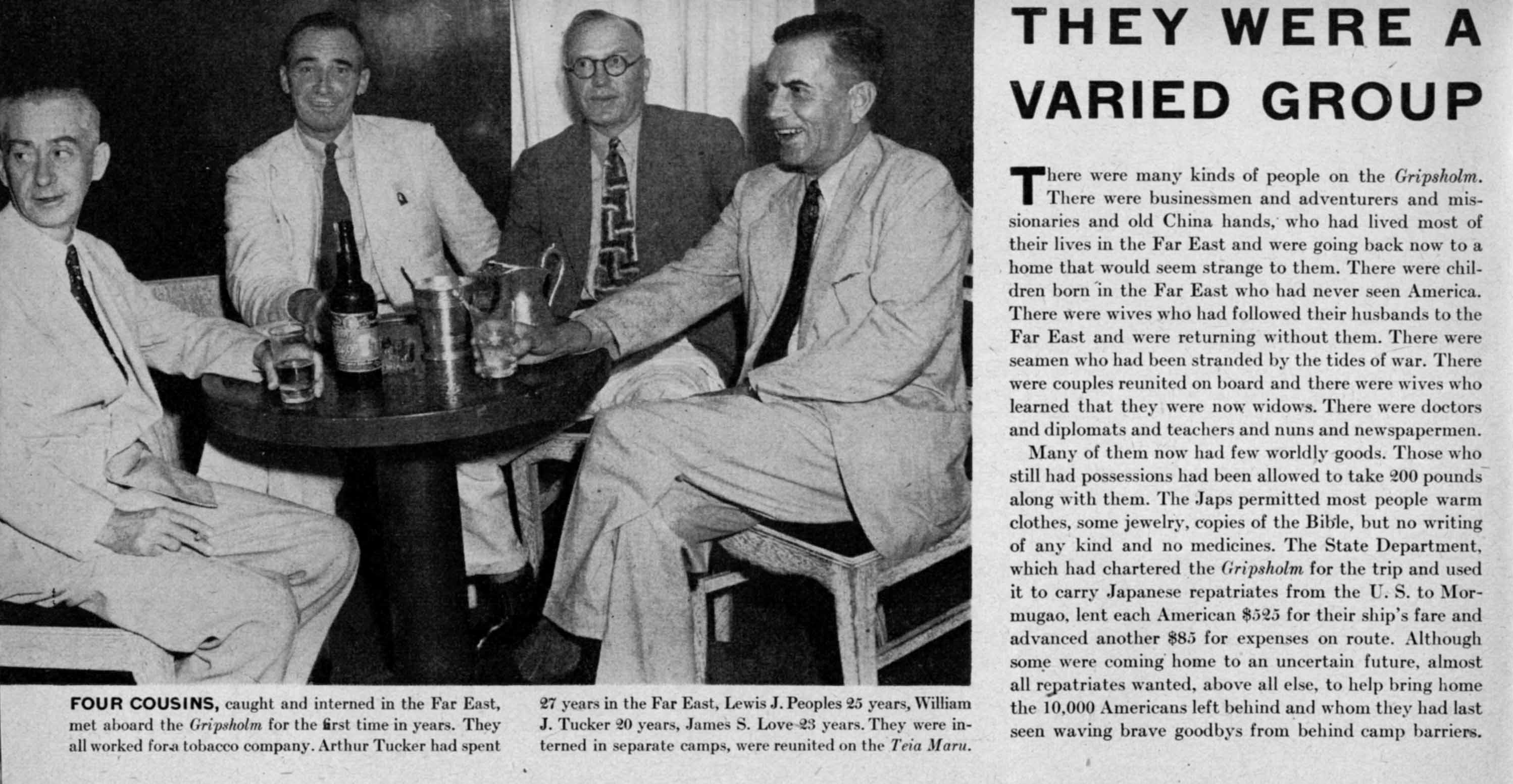

FOUR COUSINS, caught and interned in the Far East, met aboard the Gripsholm for the first time in years. They all worked for a tobacco company.

Arthur Tucker had spent 27 years in the Far East, Lewis J. Peoples 4.5 years, William J. Tucker 10 years and James S. Love 13 years. They were interned in separate camps and were reunited on the Teia Maru.

There were many kinds of people on the Gripsholm. There were businessmen and adventurers and missionaries and old China hands, who had lived most of their lives in the Far East and were going back now to a home that would seem strange to them. There were children born in the Far East who had never seen America. There were wives who had followed their husbands to the Far East and were returning without them. There were seamen who had been stranded by the tides of war. There were couples reunited on hoard and there were wives who learned that they were now widows. There were doctors and diplomats and teachers and nuns and newspapermen.

Many of them now had few worldly goods. Those who still had possessions had been allowed to take 200 pounds along with them. The Japs permitted most people warm clothes, some jewelry, copies of the Bible, but no writing of any kind and no medicines. The State Department, which had chartered the Gripsholm for the trip and used it to carry Japanese repatriates from the U. S. to Mormugao, lent each American $525 for their ship's fare and advanced another $85 for expenses on route. Although some were coming home to an uncertain future, almost all repatriates wanted, above all else, to help bring home the 10,000 Americans left behind and whom they had last seen waving brave goodbyes from behind camp barriers.

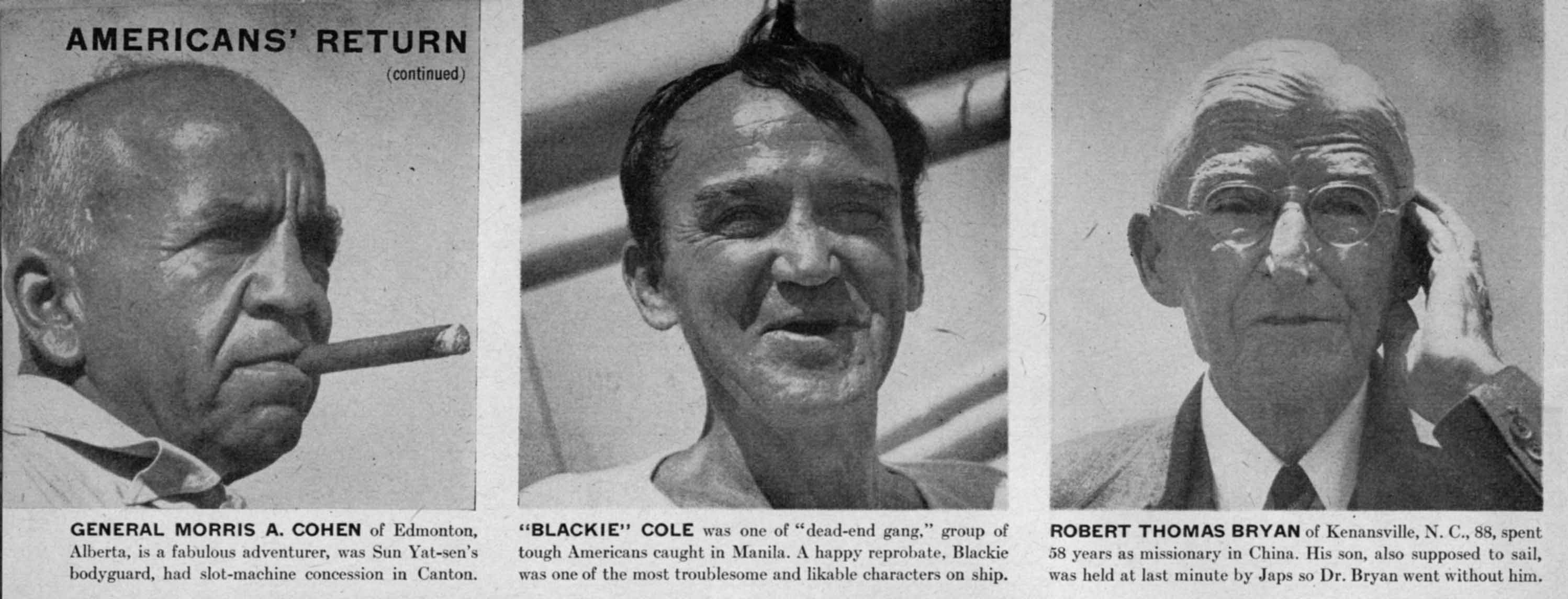

GENERAL MORRIS A. COHEN of Edmonton, Alberta, is a fabulous adventurer, was Sun Yat-sen's bodyguard, had slot-machine concession in Canton.

"BLACKIE" COLE was one of "dead-end gang," group of tough Americans caught in Manila. A happy reprobate. Blackie was one of the most troublesome and likable characters on ship.

ROBERT THOMAS BRYAN of Kenansville, N. C., 88, spent 58 years as missionary in China. His son, also supposed to sail, was held at last minute by Japs so Dr. Bryan went without him.

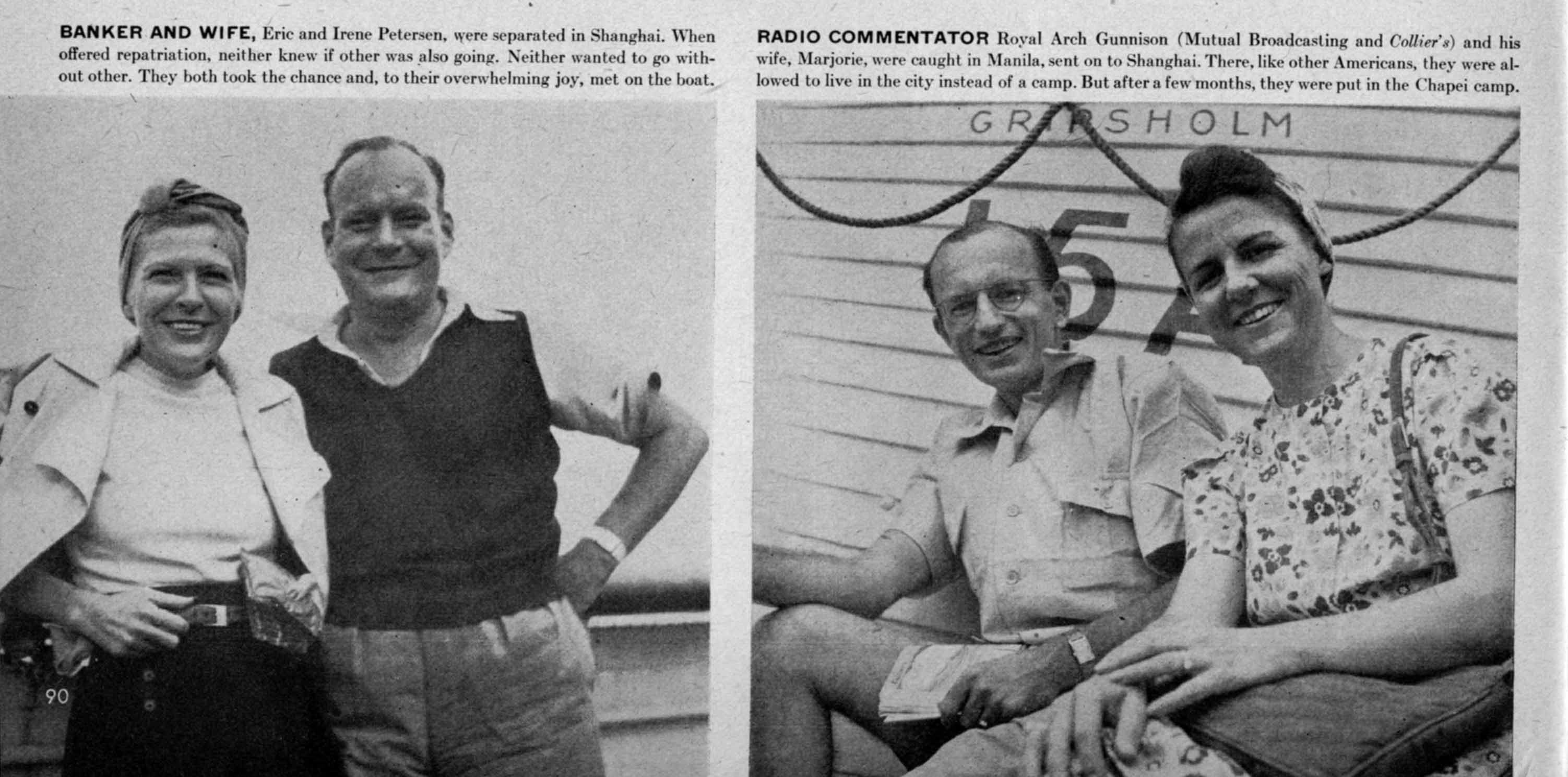

BANKER AND WIFE, Eric and Irene Petersen, were separated in Shanghai. When offered repatriation, neither knew if other was also going. Neither wanted to go without the other. They both took the chance and, to their overwhelming joy, met on the boat.

RADIO COMMENTATOR Royal Arch Gunnison (Mutual Broadcasting and Collier's) and his wife, Marjorie, were caught in Manila, sent on to Shanghai. There, like other Americans, they were allowed to live in the city instead of a camp. But after a few months, they were put in the Chapei camp.

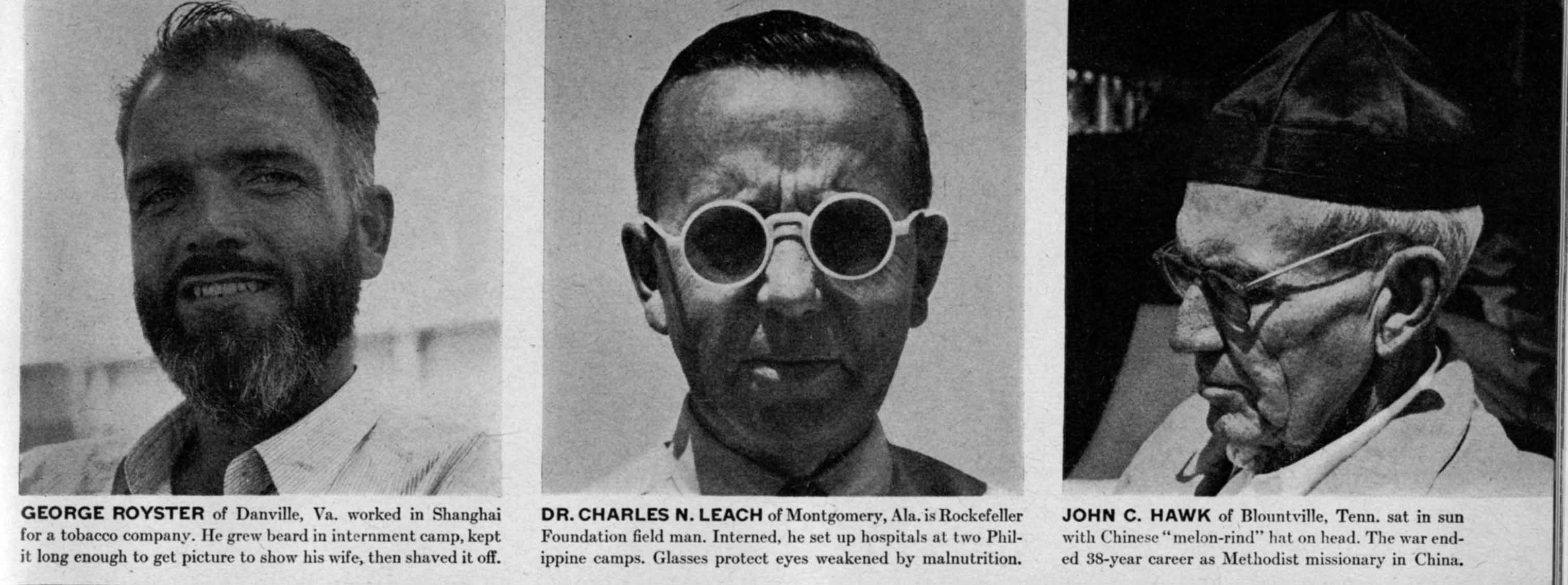

GEORGE ROYSTER of Danville, Va. worked in Shanghai for a tobacco company. Ile grew beard in internment camp, kept it long enough to get picture to show his wife, then shaved it off.

D R. CHARLES N. LEACH of Montgomery, Ala. is Rockefeller Foundation field man. Interned, he set up hospitals at two Philippine camps. Glasses protect eyes weakened by malnutrition.

JOHN C. HAWK of Blountville, Tenn. sat in sun with Chinese "melon-rind" hat on head. The war ended a 38-year career as Methodist missionary in China.

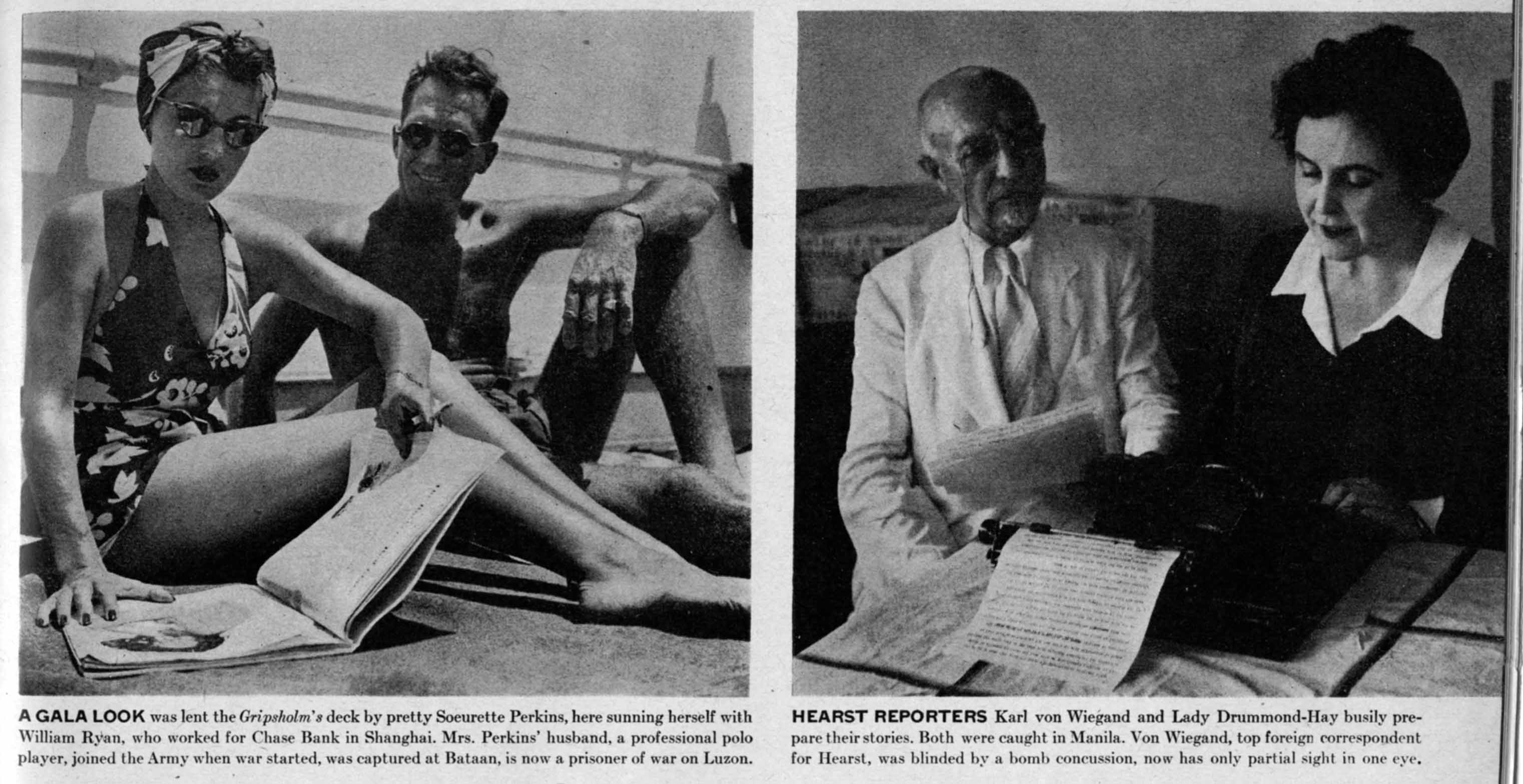

A GALA LOOK was lent the Gripsholm's deck by pretty Soeurette Perkins, here sunning herself with William Ryan, who worked for Chase Bank in Shanghai. Mrs. Perkin's husband, a professional polo player, joined the Army when war started, was captured at Bataan, is now a prisoner of war on Luzon.

HEARST REPORTERS Karl von Wiegand and Lady Drummond-Hay busily prepare their stories. Both were caught in Manila. Von Wiegand, top foreign correspondent for Hearst, was blinded by a bomb concussion, now has only partial sight in one eye.

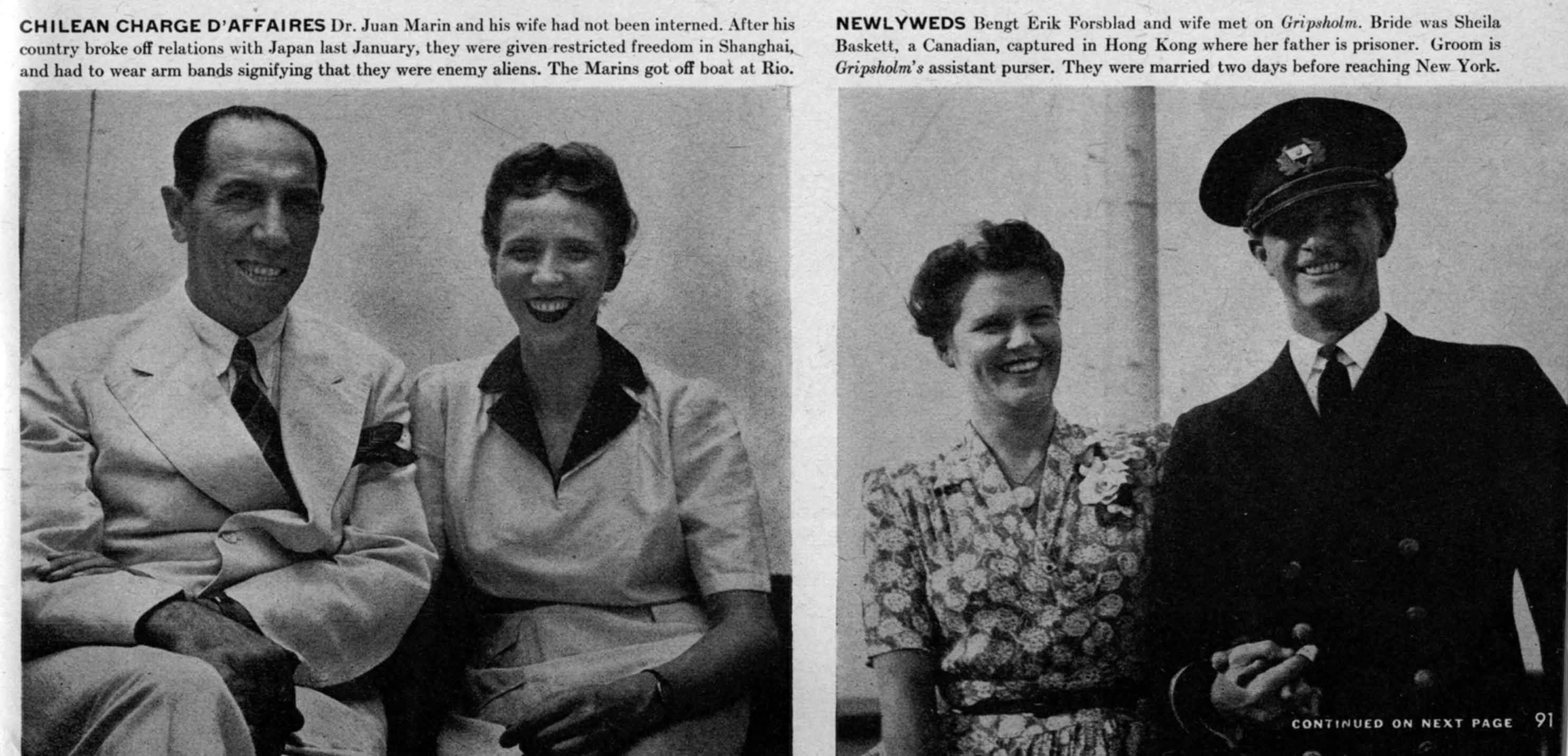

CHILEAN CHARGE D'AFFAIRES Dr. Juan Marin and his wife had not been interned. After his country broke off relations with Japan last January, they were given restricted freedom in Shanghai, and had to wear armband signifying that they were enemy aliens. The Marins got off boat at Rio.

NEWLYWEDS Bengt Erik Forsblad and wife met on Gripsholm. Bride was Sheila Baskett, a Canadian, captured in Hong Kong where her father is prisoner. Groom is Gripsholm's assistant purser. They were married two days before reaching New York.

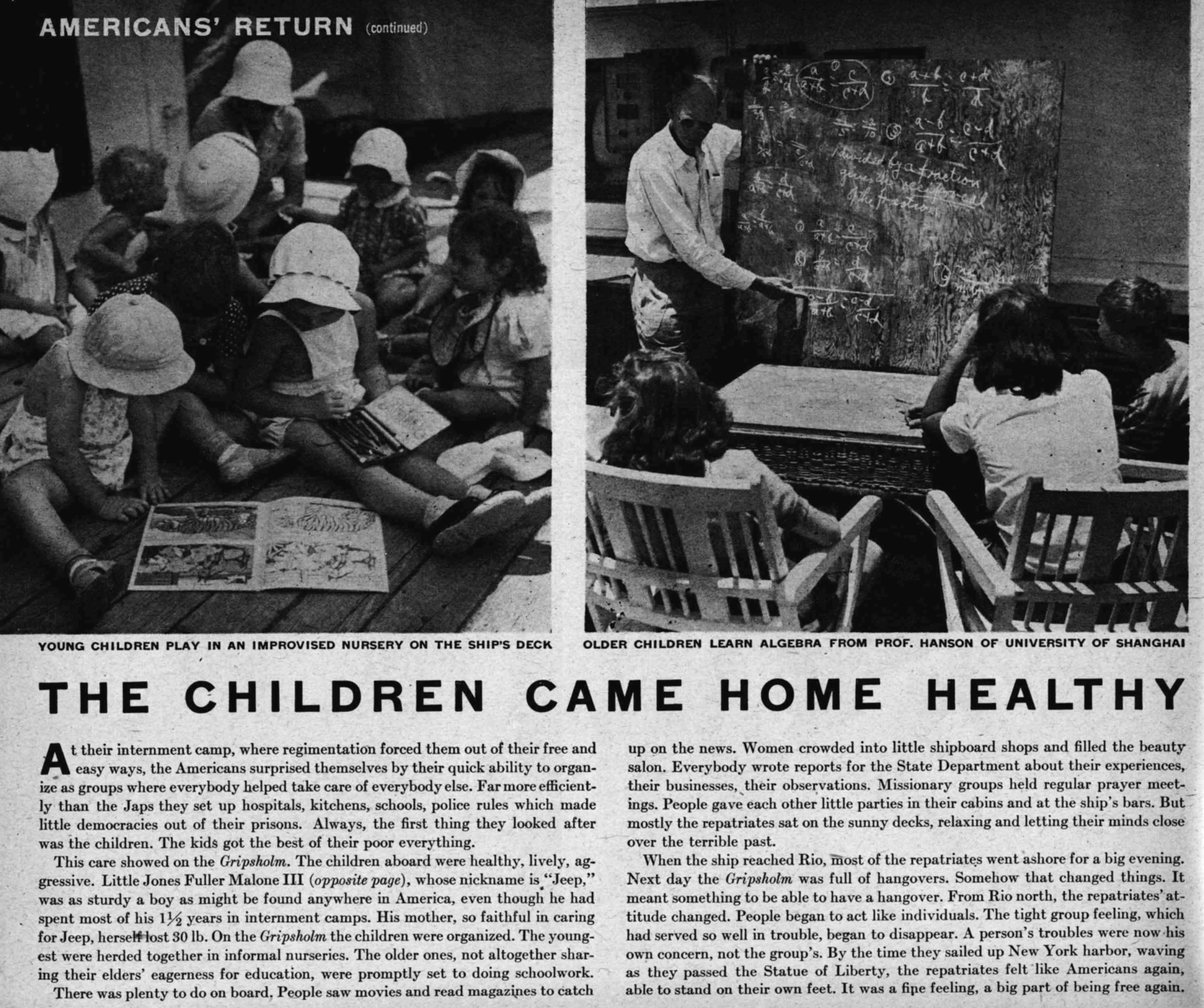

THE CHILDREN CAME HOME HEALTHY

At their internment camp, where regimentation forced them out of their free and easy ways, the Americans surprised themselves by their quick ability to organize as groups where everybody helped take care of everybody else. Far more efficiently than the Japs they set up hospitals, kitchens, schools, police rules which made little democracies out of their prisons. Always, the first thing they looked after was the children. The kids got the best of their poor everything.

This care showed on the Gripsholm. The children aboard were healthy, lively, aggressive. Little Jones Fuller Malone III (opposite page), whose nickname is "Jeep," was as sturdy a boy as might be found anywhere in America, even though he had spent most of his 1½ years in internment camps. His mother, so faithful in caring for Jeep, herself lost 30 lb. On the Gripsholm the children were organized. The youngest were herded together in informal nurseries. The older ones, not altogether sharing their elders' eagerness for education, were promptly set to doing schoolwork.

There was plenty to do on board. People saw movies and read magazines to catch up on the news. Women crowded into little shipboard shops and filled the beauty salon. Everybody wrote reports for the State Department about their experiences, their businesses, their observations. Missionary groups held regular prayer meetings. People gave each other little parties in their cabins and at the ship's bars. But mostly the repatriates sat on the sunny decks, relaxing and letting their minds close over the terrible past.

When the ship reached Rio, most of the repatriates went ashore for a big evening. Next day the Gripsholm was full of hangovers. Somehow that changed things. It meant something to be able to have a hangover. From Rio north, the repatriates' attitude changed. People began to act like individuals. The tight group feeling, which had served so well in trouble, began to disappear. A person's troubles were now his own concern, not the groups. By the time they sailed up New York harbor, waving as they passed the Statue of Liberty, the repatriates felt like Americans again, able to stand on their own feet. It was a fine feeling, a big part of being free again.

CAROLA BOXER, 2 years old, daughter of Writer Emily Hahn, was born in Hong Kong. Her father, a British colonel, was captured, is still a prisoner there. Carola speaks only Cantonese and Mandarin Chinese.

GRETCHEN WHITAKER, age three weeks, was born aboard the Teia Maru off Singapore, with eight Japanese nurses and one Japanese doctor in attendance. She has birth certificate in Japanese and English. Her father was U. S. vice-consul in Manila.

LINDA JEAN WATKINS, 17 months, was born in occupied Manila. Linda's mother, Ellie Watkins, last saw her Navy-officer husband on Christmas Eve, 1941. Twice she got reports that he was dead. On Gripsholm, she learned that he was still alive.

/logo.png)