February 20, 2014.

The establishment in Weifang,

known as Weihsien

Concentration Camp, was the

largest Japanese camp in China.

It housed prisoners from

many countries during World

War II. Most of the internees

endured three years there.

Rotten meat

Edmund Pearson, 78, a

retired Canadian engineer and

businessman was among the

internees. Although he was

just 6 years old when he was

interned, he remembers everything.

Fearing the internees could

make contact with the outside

world or even escape, the Japanese

covered the walls with

electrified wires and set up

searchlights and machine guns

in the guard towers. The camp

was under military management

and the internees were

forced to wear armbands displaying

a large black letter to

indicate their nationalities —

“B” for British, “A” for American,

and so on.

“We were there as a family

and lived in a small room with

no sanitary facilities. I have

many memories of the camp,

such as being counted by the

Japanese three times a day,

attending school, being hungry

most of the time. I was 6,

but still had to work. My job

was that of a bell ringer, waking

people for the first roll call.

The latrines were awful because

we moved from flush toilets to

‘squatters’,” Pearson recalled.

“We very seldom had meat,

and when we did it was often

rotten. We had a lot of eggplants,

to the extent that afterward

I could not eat eggplant

until I was in my 30s. As children

we still had school, but

the teenagers also had jobs.

My older brother worked as a

cobbler,” he said. “Coffee and

tea was reused, over and over.

We arrived in late fall, around

October, so our living quarters

were very cold.”

Pearson remembered that

the adults made young children

eat powdered eggshells to prevent

rickets. “They got eggs on

the black market and the shells

had to be saved and powdered.

There’s nothing worse than

eating a spoonful of powdered

eggshell,” he said.

British writer Norman Cliff

was 18 when he entered the

camp. In his memoirs, he said

that every effort was spent

acquiring fuel, food and clothing.

“The fortunes of war produced

some strange situations,”

he wrote. “One fine British Jewish

millionaire could be seen

working regularly through a

pile of ashes behind the kitchen,

and a leading female socialite

could be seen chopping wood.

Our bodies were tired from

long hours of manual labor. We

often went to bed longing for

more food. Two slices of bread

and thin soup were hardly a satisfying

supper after a day spent

pumping water and arraying

heavy crates of food.”

Loss of dignity

Some people have called

Weihsien camp “the Oriental

Auschwitz”.

“Because of the poor sanitary

conditions and the shortages of

food and medical care, several

people died in the camp. But

still I don’t agree with calling it

‘Auschwitz’ because there was

no slaughter there. That’s the

truth. Japan mainly wanted to

humiliate the allied countries,”

said Xia Baoshu, 82, a Weihsien

camp researcher and former

president of Weifang People’s

Hospital.

Mary Taylor Previte, 81,

who later served in the New

Jersey General Assembly, was

interned at the age of 9.

“The second day after the

attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese

soldiers appeared on the

doorstep of our school. They

said we were now prisoners of

the Japanese. I remember so

well when the Japanese came

and marched the school away

— perhaps 200 teachers, children

and old people — to the

concentration camp. I will

never forget that day. A long,

snaking line of children marching

into the unknown, singing

a song of hope from the Bible,”

she said.

“Separated from our parents,

we found ourselves crammed

into a world of gut-wrenching

hunger, guard dogs, bayonet

drills, prison numbers and

badges, daily roll calls, bed

bugs, flies and unspeakable

sanitation.”

A time of heroes

For Previte, the story of the

camp is one of heroes, hope and

triumph. It shaped her life.

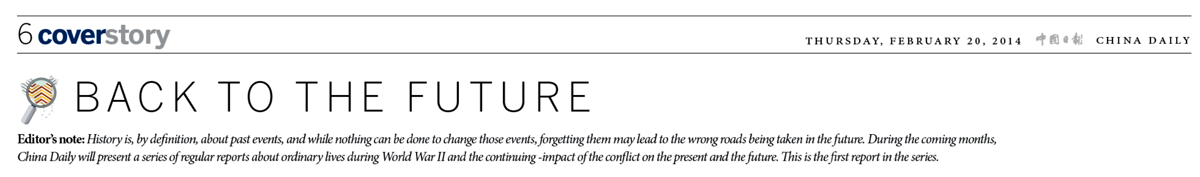

“Weihsien is a story of Chinese

heroes — farmers who

risked their lives to smuggle

food over the wall to prisoners

— we called it the ‘black market’

— and those who brought

us food so generously when the

war was over,” she said.

Xia recalled: “Some peasants

operating the black market

were caught red-handed and

tortured. Some were killed.

The camp was closely guarded.

Apart from the Japanese, only

Zhang Xingtai and his son, who

cleaned the latrines, could enter

and leave the camp freely. They

took many risks to help internees

deliver important messages

and also helped Arthur W.

Hummel (called Heng Anshi

in Chinese) to escape,” he said.

Zhang Xihong, 84, Zhang

Xingtai’s youngest son, remembered

the aftermath. “After

Heng escaped, the Japanese

immediately caught my father

and brother. They were heavily

beaten and tortured, but neither

gave in. They were finally

released because of a lack of evidence.

They came back with

injuries and blood everywhere.

They are heroes in my heart,

because my father never regretted

what he had done,” he said.

Zhang’s story was echoed

by Wang Hao, director of the

Weifang Foreign and Overseas

Chinese Affairs Office.

“The supply of food to the

camp dwindled and the internees

suffered a lot from longterm

hunger. The local people

donated more than $100,000, a

lot of money at that time, to buy

food, medicines and necessities

that they managed to send into

the camp to help the internees

survive the toughest periods,”

he noted.

Hopes of survival

Pearson said the children

were lucky because the adults

quickly formed a camp committee.

They restarted the

school, hospital, and church,

and even set up an entertainment

committee that put on

oratorios, plays and ballets.

Cheng Long, a professor

at the Beijing Language and

Culture University, has just

returned to China from the US

where he interviewed surviving

internees. “The deeper I

research the history, the more

I am interested in it. I found

that even in such harsh conditions,

the internees maintained

a positive attitude toward life.

The Japanese didn’t allow the

band to practice, so instead

of making a sound, they kept

practicing by gestures in the

hope of playing on victory day.

Even under such hardship and

without freedom, their paintings

still featured bright colors

— flowers, green trees and blue

skies,” he said.

The respect shown for education

moved Sylvia Zhang,

a post-doctoral researcher at

Shih Hsin University in Taiwan.

“Even in the camp, the teachers

still followed strict teaching

guidelines just like in Britain.

They held the Oxford Local

Examination in the camp for

higher-grade students to help

them deal with the changeable

future. It’s the reason that many

of the child internees were successful

after liberation,” she said

Previte said that although

children from her school were

separated from their parents,

the missionary teachers and

adults did everything they

could to protect them.

“The teachers would never

let students give up. They insisted

on good manners. We could

be sitting on wooden benches

at wooden tables in the mess

hall and eating the most awfullooking

glop out of a soap dish

or an empty tin can, but those

hero-teachers kept repeating

the rules: Sit up straight. Do not

stuff food in your mouth. Do

not talk while you have food in

your mouth,” she recalled.

Liberation

“The Japanese army was losing

ground in most of China in

1945 and victory was almost

assured, but the news was

blocked. It wasn’t until the US

arranged rescue planes to liberate

the camp on Aug 17, 1945,

that people knew their days in

hell were over,” said Cheng.

Liberation came as a surprise

to Previte. “It was a hot and

windy day. I was sick with an

upset stomach in the hospital

when I heard the drone of an

airplane over the camp. Racing

to the window, I watched

it sweep lower, slowly lower,

and then circle again. It was a

giant plane, emblazoned with

an American star. Beyond the

treetops its belly opened. I

gaped in wonder as giant parachutes

drifted slowly to the

ground. People poured to the

gate to welcome the heroes. All

the internees were celebrating

liberation and we even cut off

pieces of parachutes, and got

their signatures and buttons to

cherish,” she said.

The long years of malnourishment

affected the children’s

physical development. Even

after 70 years, the experience

of the camp can provoke nightmares

among former internees.

Pearson said that after being

so hungry for more than three

years, he will eat almost anything

now.

“I am obsessed with food,

so I do all the cooking. More

important, the camp experience

made a very strong

impression on me. It took a

long time before I could deal

with the Japanese, even though

as an adult I went to live in

Hong Kong with my family

and had to do business with

the Japanese. The people are

fine, but the government has

never acknowledged what they

did to us,” he said.

“I am obsessed with food,

so I do all the cooking. More

important, the camp experience

made a very strong

impression on me. It took a

long time before I could deal

with the Japanese, even though

as an adult I went to live in

Hong Kong with my family

and had to do business with

the Japanese. The people are

fine, but the government has

never acknowledged what they

did to us,” he said.

Previte said conflict is a

catastrophe that destroys

everything. “War and hate and

violence never open the way to

peace. Weihsien shaped me. I

will carry Weihsien in my heart

forever.”

Contact the author at hena@

chinadaily.com.cn

Of those interned

in the camp, the

only person I am in

contact with is my

cousin who was born there.

As you can imagine, we survivors

were children at the time,

and our parents decamped all

over the world afterwards.

I returned to the camp in

2005, when the city of Weifang

decided to host a week of

meetings for the survivors.

Only

seven

buildings

are left,

one being

a block of

rooms like

the one

in which

I lived,

although

it’s not

the same

one. Even though the buildings

are now surrounded by

the city, I recognized them all,

even those in which the Japanese

lived. I remember one of

them especially well, because

my brother and I would steal

coal from the basement. I also

recognized the hospital where

I had my tonsils removed.

Mostly, my feelings were pride

at the accuracy of my memory

after all these years.

I was 70 in 2005 and I was

surprised that the city had

built a memorial wall with all

of our names inscribed on it.

at the accuracy of my memory

after all these years.

I was 70 in 2005 and I was

surprised that the city had

built a memorial wall with all

of our names inscribed on it.

Edmund Pearson spoke with

He Na.

I remember one of the US

internees told me that

Weihsien camp is not

only a part of Chinese

history but also a part of US

history too. The unique history

of Weihsien camp has

provided a connection with

the rest of the world.

To allow more people at

home and abroad to know

about this history, including

key events and how people

helped each other to survive

the hard times, the Weifang

government attached great

importance to the investigations

into the history of the

camp. Staff members are in

a race against time to collect

information and stories 70

years after the event because

most of the internees have

died.

Also, the government is

drawing up a long-term plan

for the camp, and we hope to

restore some of the buildings

and to make the few buildings

that still stand into a campthemed

memorial park.

Next year will be the 70th

anniversary of the end of World

War II, and a series of memorial

activities will be carried out.

One of the most important will

invite survivors to return to

Weifang, where seminars will

be held to further study the

period.

Wang Hao spoke with He Na.