China, World War II

A mother cut off from her own youngsters.

We thought the children were safe, there on the coast of China — safe from anything. Until the Japanese invaders came.

James and I were Free Methodist missionaries, a husband-and-wife team, deep in the Chinese province of Honan. Our four children were in the Chefoo School in Shantung Province, 1000 miles away. My husband had attended that school. His grandfather, James Hudson Taylor I. had started it. The school had known four generations of Taylors, and the teachers were more family than not.

My father-in-law Herbert Taylor was there in Chefoo, too. I felt as if the children were in their own home, safe and snug. I was an American, my husband was British. We'd long been missionaries. So it seemed to me that the children would be safe anywhere in the world.

Then suddenly the Japanese swept into China. Mortars screamed overhead. Bombs plunged to the earth, maiming and killing people. Entrapping and scattering people. We were cut off! It was impossible to get back to Chefoo.

Pushing farther inland from the east, the Japanese overran Honan in 1939, and James and I ran for our lives. I was six months pregnant at the time. We escaped to the town of Fenghsiang, far, far inland, on the western border of Shensi. But my thoughts were constantly in Chefoo.

How could I have known when I married into the Taylor family, missionaries to the Chinese since the 1800s that this was how life would turn out? I had melded into their ways: of teaching and loving and sharing with the Chinese, of riding bicycles or walking or hiring the jolting horse-drawn carts, of eating with chopsticks and sleeping on a mat atop a large brick bed. China was home, and when the war came, disrupting the lives of the Chinese, splitting apart families, it did the same to the Taylors.

I sent frequent letters to Chefoo, telling the children where we were and somehow, miraculously, a few letters came to us from the children: They'd had Sunday dinner with Grandpa. Kathleen, 14, had earned another Girl Guides badge. Jamie, 10, had breezed through his exams. Mary had just celebrated her ninth birthday. John, eight, had been sick, but was much better. And, briefly, there had been some ground skirmishes between Japanese troops and Chinese guerrillas, but the school had escaped harm, and the fighting subsided.

I would take out the children's letters and reread them until they became frayed at the edges. I agonized over the lack of news. "James," I would say, "do you think the children are all right? It's been so long since we've heard anything."

With his quiet faith, James reassured me. But I saw the worry in his eyes. And I knew that his very human fear for the children's safety was just as great as mine.

I pictured them over and over — the times we had spent together reading and talking and singing around the organ. I remembered them the way they looked the day James and I left Chefoo — Kathleen in a navy blue jumper and white blouse, her long, wavy hair falling past her shoulders; Mary with her blond bob and pretty blue eyes; our sons, so young and full of promise.

"Heavenly Father, keep them safe," I prayed. "Watch over Grandpa Taylor."

The air raids sent us running for shelter day after day. Epidemics and disease raged among the Chinese soldiers. In parts of China, food was so scarce because of drought that people were eating tree bark. In the midst of this, with missionaries helping with relief programs, passing out food and clothes to refugees, James and I started the Northwest Bible Institute to prepare young people for the ministry. Somehow, we knew, God's work had to go on; and we spent long hours developing a curriculum and pre- paring teachers, then enrolling students.

One day, after teaching a class, I was just entering our house when the newspaper deliveryman came. The paper's large Chinese characters announced: "Pearl Harbor Attacked. U.S. Enters War." As I absorbed the news, I realized why there had been a long silence from the children. Chefoo had been in the Japanese line of attack.

"Oh, dear God," I whispered, "my children, my children. . ." I knelt beside the bed. Not even tears came at first, just wave after wave of anguish.

As the fear penetrated deeper, I remembered the horror stories of Nanking — where all of the young women of that town had been brutally raped. And I thought of our lovely Kathleen, beginning to blossom into womanhood. . .

Great gulping sobs wrenched my whole body. I lay there, gripped by the stories we had heard from refugees — violent deaths, starvation, the conscription of young boys—children—to fight.

I thought of 10-year-old Jamie, so conscientious, so even-tempered. "What has happened to Jamie, Lord? Has someone put a gun in his hands? Ordered him to the front lines? To death?"

Mary and John, so small and so helpless, had always been inseparable. "Merciful God," I cried, "are they even alive?"

Kneeling there by the bed, pleading with God, I knew without any doubt at all that I had no other hope but God. I reached out to Him now, completely. "Please help my children. Let them be alive, please!" Then, as if in a dream. I drifted back to a time when I was a girl of 16 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. I pictured our minister, Pa Ferguson, sitting there telling me words he had spoken years ago: "Alice, if you take care of the things that are dear to God. He will take care of the things dear to you." That was Pa Ferguson's translation of "Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness: and all these things shall be added unto you." (Matthew 6:33) It was his way of making his point to the teenagers he was working with.

In the stillness of the bedroom, I pondered Pa Ferguson's words. Who were the ones dear to God? The Chinese to whom God had called me to minister. And who were the ones dear to me? My children.

I did not know whether my children were dead or alive, nevertheless a deep peace replaced my agony. This war had not changed God's promise. With that assurance, I felt the aching weight of fear in my stomach lift.

"All right, God," I said finally. "John and Mary and Kathleen and Jamie are in Your care. With all my heart I believe that You will guard them. I know that You will bring us back together, and until that day comes. I will put all my energy into Your work. I promise."

We had a pact. God and I, and I knew He would keep His part of it. And I must keep mine.

So it went, each day — taking care of the things dear to God. Like the day at the house of Mr. Chang, whose body and mind were devastated by disease. "He will not let anyone near the house," his wife warned.

I walked to the window and called, "Mr. Chang, we have come to pray for you. You can be healed. Please let us come in." And he did! He turned his life over to God. And I knew that God was watching over my children.

There were times when I rode into the hills with our new baby Bertie strapped on my back and held open-air meetings with people in remote villages. "This is for You, Heavenly Father," I would say in prayer, "because these are Your children, dear to You." And I knew that He was caring for my children, too.

And in the compound, when I worked as a midwife delivering babies, I would say to God, "Thank You for letting me deliver this child." And I thanked Him for delivering my children from harm.

In time we received word that everyone in Chefoo School had been captured and crammed into a concentration camp in Weihsien along with 1300 other captives. But we had no way of knowing, from day to day, whether the children were alive.

People would say to me. "You have such great strength, Alice, carrying on, yet knowing that your children have been captured."

And I would say. "My strength is God's strength. I know He will not forsake my children. I know this'."

Through it all — the scarcity, the sickness, the dying, through the bombings when I didn't breathe until I heard the explosion and realized I was still alive — I did what I knew God wanted me to do. I took care of the Chinese. I passed along His Word to doctors, to army officers and troops, to students, to parents and grandparents. Over and over. Day after day.

In spare moments after school I began sewing clothes for Kathleen and Mary.

"What is that you're making, wifey?" James asked, using his usual term of endearment.

"Some pajamas for the girls, James, for when they come back. I hope I've judged the sizes right."

He was silent. Just looked at me.

Then one Sunday morning, as I held services in a village 20 miles from Fenghsiang, one of the students from the Bible Institute appeared in the crowd, pushing my bicycle, and announced,' "They say that the Japanese have surrendered!"

The crowd burst into excitement. But for days, confusion reigned. Families had been torn apart, homes demolished, records lost or burned. Communication and transportation were haphazard. People groped for life and roots.

I longed to hear some word, just to know... And as I sat one September evening in our home during a faculty meeting, my mind wandered once more to the children. Again I pictured them as I had seen them last, waving good-bye. I heard their voices, faintly, calling excitedly … then I heard their voices louder. Was I imagining this? No, their voices were real!

And they came bursting through the doorway. "Mommy, Daddy, we're home, we're home!" And they flew into our arms. Our hugs, our shouts filled the room. We couldn't let go of one another. It had been five and a half long, grueling years. Yet, there they were — thin, but alive and whole, laughing and crying. Oh, they had grown! But Kathleen still wore the same blue jumper she had worn when I last saw her. It was as God had miraculously preserved the children and returned them to us.

Later, medical checkups showed their health to be excellent. There were no emotional repercussions, and when we went to the States a year later, our children were two years ahead of students their own age.

While many in Japanese concentration camps suffered horrors, the children of the Chefoo School were spared. They received dedicated care from their teachers, and when there was not enough food to go around, the teachers helped the children gather wild edible plants. They continued their lessons and they attended church. Jamie looked after Grandpa Taylor, who was flown back to England after the war. And today Jamie—James Hudson Taylor III — works with Overseas` Missionary Fellowship in Singapore.

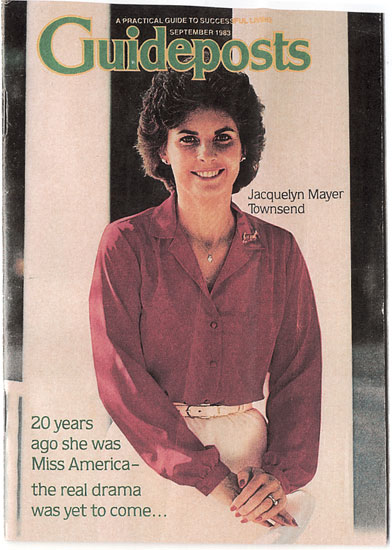

For our family, that advice from Pa Ferguson long years ago will always hold special meaning. I pass it along to you, for it is truly so: “If you take care of the things that are dear to God, He will take care of the things dear to you.”

e thought the children were safe, there on the coast of China — safe from anything. Until the Japanese invaders came.

Mary Remembers the Day …

I will never forget that sight — large yellow and white poppies floating down from the sky. American paratroopers dropped to the ground, and like a great human sea, all 1400 captives swept out of our concentration camp to meet them!

Grandpa Taylor was on the first plane-load flown out we four Taylor children were on the second. We were flown to Sian, 100 miles from home. A Chinese friend of Father's took us by train to within 15 miles of Fenghsiang, then hired a cart and began driving us in the rain down the rutted road. It was dusk.

But the mule was too slow for us, and we jumped off the cart and raced ahead, sloshing barefoot through the mud until we met one of our parents' students, who led us through a moon gate, then across the Bible school compound. We saw our parents through the window, and we ran stumbling and shouting, "Mommy! Daddy!" through the doorway and into their arms.

Years ago, Mother had taught us to sing Psalm 9.1: He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty... " God had been with us those five and a half years. And the night he brought us back together was like a dream come true. No, it was even more; it was a promise come true.

Mary Taylor Previte

will never forget that sight — large yellow and white poppies floating down from the sky. American paratroopers dropped to the ground, and like a great human sea, all 1400 captives swept out of our concentration camp to meet them!