REPRODUCED AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES

REQUIRED

By Department’s Special Division Memorandum of August 26, 1943

Released: January 4, 1944

From Samuel Sobokin, American Consul November 9, 1943

On board GRIPSHOLM, Date of mailing: December 1, 1943.

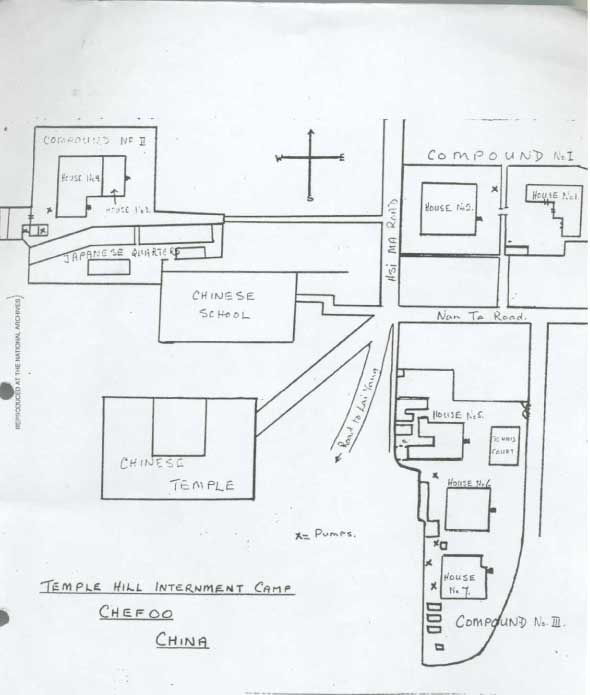

INTERNMENT OF AMERICANS AND ALLIED NATIONALS AT CHEFOO, CHINA, IN TEMPLE HILL COMPOUNDS.

Chefoo, China

Temple Hill Internment Camp

Temple Hill Internment Camp

I - INTRODUCTION

American and Allied nationals at Chefoo, China with certain exceptions were not interned until October 29, 1942, and November 4, 1942. On the latter date all those connected with the China Inland Mission were interned while the others were interned on the earlier date.

The China Inland Mission conducted a large school at Chefoo, and on its premises, on November 4, 1942; there was a total of 239 men, women and children who were, interned.

The other residents interned in Chefoo numbered 119, composed of missionaries and their families and members of the business community. Only one exception to the internment order was made by the Japanese; an invalid Greek girl, her mother and grandmother, were exempted.

On Thursday morning, October 29, 1942, the Japanese military visited the homes of the American, British, Dutch, Greek and Norwegian citizens, except those living in the China Inland Mission, announcing they must leave and be at house No. 2 of the Presbyterian Mission (Kidder House) in Chefoo by 12 o'clock noon. Some were notified as early as 8 a.m., others after 11 o'clock, and all were told to be at the location by noon. They were instructed to take their money, clothes, food, and bedding; this latter may include a mattress but not a bed. Some were told to leave most of their clothes as they would be back in four, or five days.

On Thursday morning, October 29, 1942, the Japanese military visited the homes of the American, British, Dutch, Greek and Norwegian citizens, except those living in the China Inland Mission, announcing they must leave and be at house No. 2 of the Presbyterian Mission (Kidder House) in Chefoo by 12 o'clock noon. Some were notified as early as 8 a.m., others after 11 o'clock, and all were told to be at the location by noon. They were instructed to take their money, clothes, food, and bedding; this latter may include a mattress but not a bed. Some were told to leave most of their clothes as they would be back in four, or five days.

Others were not allowed to take much bedding. There was no uniformity about the amount of baggage permitted. Transportation to the camp was arranged by the individuals as best they could, rickshaws chiefly being used.

The residents of the C.I.M. compound were notified by the military to be ready for moving in a week's time. This gave opportunity for packing and sorting of personal effects for the disposition of such things as seemed impractical to move. Beds, springs, cooking stoves, and almost all other furniture, were not permitted to be taken. Dishes, cooking utensils, clothing, a very few heating stoves, mattresses, and other bedding (pukai's) and limited quantities of books were packed and transferred by hand carts and by trucks (the latter being furnished by the Japanese authorities.) Expenses for carts and rickshaws were paid by the mission authorities.

Strict examination was made of all things taken out of the compound, and some things were turned back as not being permitted. Some few babies' beds were permitted, and a very few chairs (possibly a dozen at the most.) At the C.I.M. compound our own servants helped with the packing and loading, but at the arrival at Temple Hill only the barrow men and cart men were allowed in and permitted to assist.

Consequently our own men and older boys were kept busy in moving the various loads. In the confusion attendant upon arrival in new quarters, quite a number of boxes and loads were miscarried, and many of these never arrived at all. With the exception of the use of the army trucks, all expenses for the transfer were paid by the internees. No limit was given about the quantity of food taken in (the Japanese at this time were not assuming any responsibility for the feeding of the center). In the same way personal money was taken in by the internees, and no questions asked by the Japanese; the same applied to clothing and personal effects, except for cameras, typewriters and radios.

The internees were registered by the Japanese military as they entered the compound gates of the camp at Temple Hill, and the first internees were assigned by the Japanese to particular rooms in the houses in compound No. 1.

Organization of Camp,

Upon arrival at the Temple Hill Compounds and the installation of the internees in the houses there, the Japanese authorities directed the internees in each of the houses to form their own administrative organizations. The Japanese made it plain that the responsibility for the internal administration rested on the internees themselves and that the internees would also have to support themselves; that is, the maintenance of the internees would be the responsibility of the internees, not themselves.

There were accordingly set up administrative committees in each of the houses in which the internees were lodged. While it might seem that so many committees were unnecessary, household economy in each particular building and the fact that the seven houses were situated in three compounds separated from each other, passage between which was not permitted except by pass, required the installation of these several committees.

Japanese Control

The Japanese military designated a Japanese commandant for all three compounds. He was situated at Japanese headquarters in the city. For about a week Japanese soldiers guarded the compounds day and night; thereafter their places were taken by Chinese policemen. In the initial period the commandant visited the compounds fairly frequently, but with the passage of time his visits became less and less frequent, and with the result that the internees' urgent problems were neglected, since the internees could not leave the compound without a pass, the commandant being the only one who issued the passes; and the internees had no means of communicating with the commandant.

In March, 1943, a Japanese commandant was installed in one of the camp compounds (No. 2) in charge of all three compounds. This commandant was the head of the Japanese consular police detailed to guard the compounds. This change resulted on the one hand in obtaining more prompt consideration of certain camp problems, while on the other hand there was a stricter enforcement of the regulations: roll call of the internees was made twice a day.

The Temple Hill Internment Camp at Chefoo was disbanded when the internees were transferred on September 8, 1943, to the camp at Weihsien, Shantung, China. A total of 296 men, women, and children made the journey to Weihsien by steamer and rail.

Early in August, 1943 Mr. Kosaka, Chief of the Chefoo camp police guard, informed the Catholic priests in the camp that they were to be transferred to Peking. This information prompted an internee to ask the chief if this meant that the Chefoo internees were to be sent to the Weihsien Camp. The Chief of Police replied that he had not intended to mention it, but since he was asked, he would state that the transfer was under consideration. Within a few days he informed Mr. P. A. Bruce, Principal of the China Inland Mission Schools, that all the internees were to be moved to Weihsien in September in four groups, one group per week. When asked the reason for the transfer to Weihsien, he replied that it was a measure of economy for his government. Asked what could be taken by the internees from Chefoo to Weihsien, he said that he would make inquiry. Later, he informed the internees that they need not take kitchen utensils, beds, mattresses, chairs or crockery, as all of these articles were provided by his government for the internees at Weihsien.

The group of Americans who were to be repatriated in 1943 left Chefoo for Weihsien ten days before the other internees were moved. On learning from them that the Chefoo internees had been instructed not to bring the above mentioned things, the Weihsien Camp internees at once took up with the Japanese authorities the urgent need of telegraphing to the Chefoo internees that they must bring all their equipment. A promise to do so was made, but official word to that effect was never given to the Chefoo internees. However, through private sources in Tsingtao those internees still in Chefoo learned of the desirability of 'taking' with them the articles above named.

Fortunately, many internees at Chefoo doubted the word of the Japanese authorities, and took all they could. They, however, were hampered by the selfish restrictions laid down by the Japanese guards and by the physical possibility of getting ready so much baggage on such short notice, for instead of being moved in four groups, one group each week, the remaining internees were sent off from Chefoo to Tsingtao on one steamer after ten days’ notice. As the ship had very limited cabin accommodations, most of the 300 internees slept either in the hold or on the deck. They had been told to take food for the trip, but in moving the baggage from the camp to the ship, many bedding rolls and food baskets were put in the hold under the heavy baggage and could not be secured. After 24 hours on the ship, they were herded on to the train at Tsingtao, and reached Weihsien hungry, thirsty, dirty and weary. (The ages of the internees ranged from 3 months to 89 years.)

Their baggage was sent by freight from Tsingtao to Weihsien, and was criminally looted en route. The looters seemed especially to want heavy clothing, shoes and bedding. Evidently several pieces were opened at a time and a choice made. Rejected items were worn often returned to wrong pieces of baggage. The loss of bedding and clothing was a very serious matter to some families, in view .of the impossibility of replacement.

II - LOCATION.

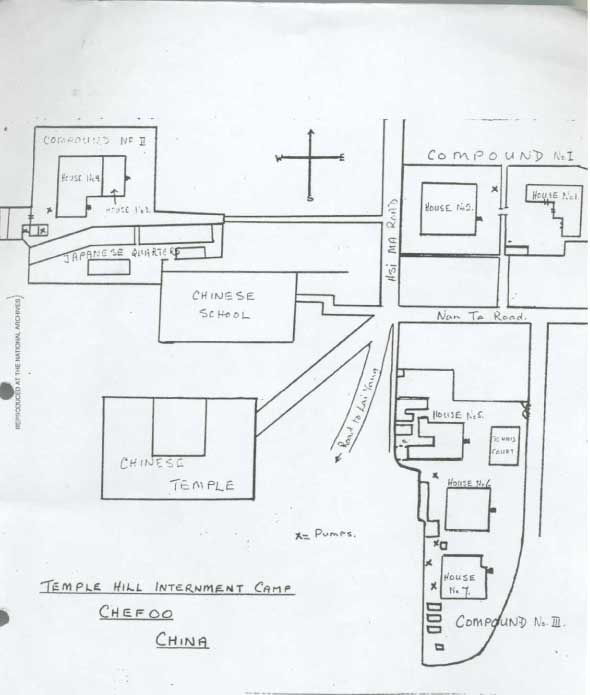

Name and exact location of camp with description of distinguishing features or surroundings (so as to be identifiable from the air):

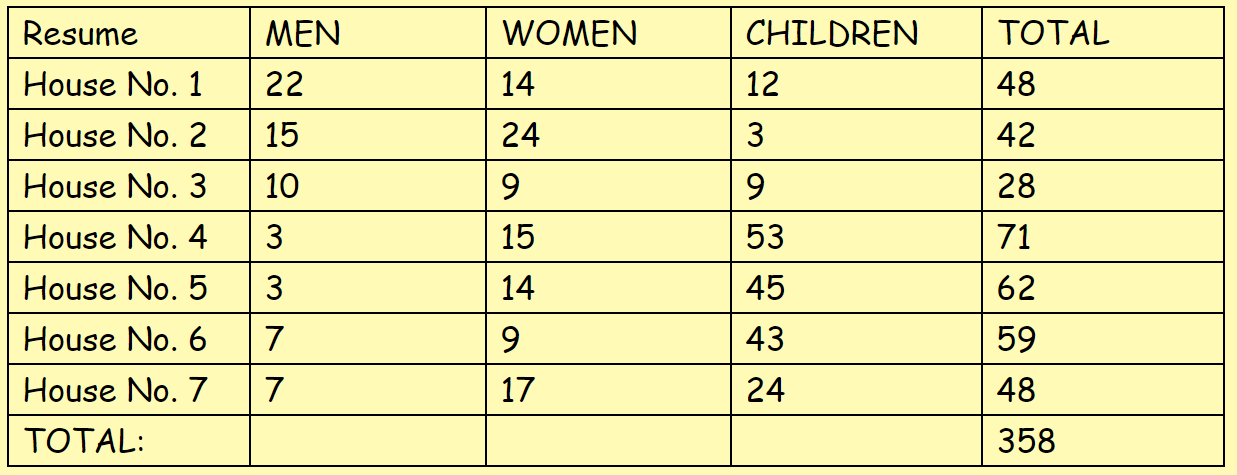

Number of internees broken down by sexes, nationality, race and age-groups.

The official name of the internment camp was "Chefoo Civil Assembly Center", and as stated previously, was located in the compounds of the American Presbyterian Mission on Temple Hill. Seven residences with servants’ quarters were used. These residences are on the north, east, and southeast side of the hill which itself is the northern end of a ridge of high hills bounding Chefoo on the east, south and west. It is easily distinguished from the air by its being at the western end of this ring of hills, by a large temple with two high flagpoles, set garden in the southeast, and by a large tile-roofed two-story school building on the northeast of the hill. On the eastern slope of the hill, more than half way down, are the three large buildings of the Temple Hill Mission hospital, set in a large well enclosed yard. Lower down on the north-eastern slope is an octagonal church with grey tiled roof and belfry at the northeast corner of the church. This Chefoo camp is now closed as the internees were transferred to Weihsien early in September, 1943.

III - DESCRIPTION.

Description of premises (photographs if possible) kind of buildings (e.g. barracks, abandoned factories, and school or college buildings); estimate of square and cubic feet per internee; lighting and heating facilities (hours when available); kind and amount of bedding provided. Beds and nets.

The internment camp at Chefoo was located in the private, foreign style, dwellings of the American Presbyterian Mission. These houses consisted of five single family houses and one two-family house, making two residences, arranged in three groups or camps.

Group I

... consisted of the Dilley and Kidder houses, known by the internees and Japanese as houses No. 1 and No. 2 respectively. These two houses, together with servants' quarters and small garden, were enclosed within a compound wall, (compound No. 1).

Group II

... consisted of the two-family house known as the Brown-Irwin house, and designated in camp as houses No. 3 and No. 4. This house together with servants' quarters was also enclosed within a compound wall (compound No. 2).

Group III

... consisted of the single family houses known as the Berst, Young and Lanning houses and designated respectively as houses No. 5, No, 6 and No. 7. These houses, together with servants' quarters, were likewise enclosed within a compound wall (compound No. 3). The townspeople, were located in houses No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3, while houses No, 4, No. 5, No, 6 and No, 7 were occupied by the China Inland Mission group. Photographs and plans of these houses may be obtained from the Presbyterian Board for Foreign Missions, 156 Fifth Avenue, New York City.

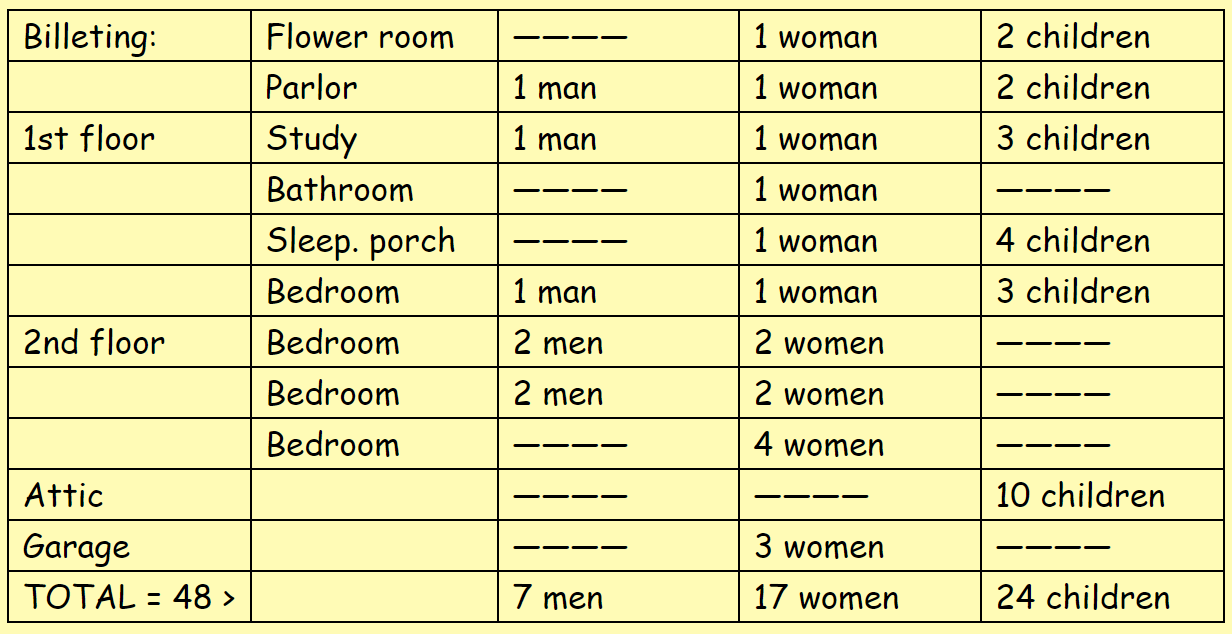

(** pages 5, 6 and 7 = missing !? ** BILLETING)

IV - COMPOUND

HOUSE NO.7

Description:

A large foreign style stone house; first floor has three rooms, flower room, kitchen, bath; second floor 4 rooms, sleeping porch, 2 baths; has good basement, attic, and garage.

HEATING

Houses Nos. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 were equipped with central heating but all except houses Nos. 3 and 4 used small stoves in various rooms for reasons of economy.

The houses used were the usual type of missionary foreign style. Residence No. 4 was a large bungalow with a fairly adequate heating plant, an extensive attic which was used as a dormitory for 36 girls. In the other houses the heating was provided by stoves (a few being brought over). There were grates in some of the rooms. In most cases bedrooms were unheated, but stoves were placed in halls and in common rooms. One house had a hot air furnace, but this was not used as it was in need of major repairs.

The internees paid for the fuel out of their comfort allowance provided after January 27, 1943. Prior to this time the “??? (smudge)” fuel with their own personal funds.

Most of the residents and schools had good supplies of coal at their original residences, but none of this fuel was allowed to be brought over to Temple Hill. Upon arrival at Temple Hill there was some supply of coal on the premises for which payment was made to the owners.

LIGHTING

Electricity was supplied from the city current, which was usually available 24 hours a day, and paid for, by the group of internees in the several houses.

BEDS AND BEDDING

With the exception of a few beds which were found in the houses upon arrival, beds were made on the floor or upon trunks and boxes, which had been brought along. There were no mattresses, beds, bedding or nets provided by the Japanese. Permission was given for bringing our own mattresses and a very few people had folding cots.

Neither beds, cots, mosquito nets nor bedding was supplied by the Japanese authorities at any time. The internees supplied mattresses and bedding from their homes or borrowed from their follow internees. At the China Inland Mission Compound in Chefoo there were left 500 beds which the Japanese refused the members and school children (the mission conducted a large school for children of missionaries residing in the interior) to take to the Temple Hill Internment Camp.

V - SANITATION

Facilities for washing, bathing, laundry, sewage and garbage disposal, etc., number and kind of toilets, supply of toilet paper.

WATER SUPPLY

Chefoo has no water works system. Water is supplied from wells by hand pumps. In the Temple Hill Compound all water had to be pumped by the internees from wells; 100 to 190 feet deep.

WASHING AND BATHING FACILITIES

Schedules had to be arranged for each of the seven houses for bathing. The water supply and the number of persons permitted only one bath per week. Where it was possible water was heated in the bath rooms. Otherwise hot water had to be carried up from heating stoves in the basement. The daily provision of hot water was also made through the basement water heaters.

TOILETS

In each compound there was a septic tank which had been built by the mission for family use only. These were entirely inadequate for such large numbers and were not used after the first few days. In each house there were two or three commodes for the use of women only. Commodes for the men were placed in the out-houses. All these were emptied and cleaned several times a day by men of our sanitary squad. The contents were dumped into large covered crooks in the garden. These were emptied daily by the city sanitary coolies. Pits were dug and lined with brick and concrete in all but one of the gardens. These we thought to be septic tanks, but the work was never completed. Toilet paper was purchased by each house from its regular house allowance, or by individuals.

SEWAGE

Kitchen and wash water was drained into deep pits dug in the garden by internees. This was far from satisfactory. Repeated requests by house No. 2 were made to the Japanese Chief of Consular Police for direct underground drainage to street sewer drain. This was finally completed just one month before the camp was moved to Weihsien. As there were flies in very large numbers the garbage disposal proved a very real problem. Deep pits were dug by the internees into which garbage was dumped and covered over with ashes several times a day.

SCREENS

All the houses except House No. 1 were screened. Those belonging to House No. 1 had been destroyed, and the authorities took no interest in replacing these. Flies were such a menace in that house that the internees themselves bought screens for the kitchen. Great pride was taken by the internees in keeping their yards clean and attractive.

LAUNDRY

Individuals or families did their own washing in the laundry room of each house or out of doors. For the first five months some were able to send their laundry out to their servants. A public laundry did some work for the internees but the service was irregular, expensive and unsatisfactory. Privately owned wash tubs and boards were turned over to the house for general use. Water for each house was pumped into tanks by our own men from deep piped wells on compounds. Hot water was supplied by native-made water heaters. Additional hot water could be purchased from a Chinese shop near the compound gate.

VI - FOOD AND CLOTHING.

Facilities for and method of preparing food. Sources and handling of food. Food and clothing provided by Japanese. Relief supplies from International Red Cross; gift packages. Purchases of food and clothing by internees with their own funds. Post exchanges and canteens. Influence of local food situation on diet provided by Japanese.

Preparation and cooking of food was done entirely by the internees. At one time a tentative promise was made that Chinese help might be provided to do the roughest work, stoking, cleaning of pots and pans, etc., but this was never permitted. The internees were divided into shifts, who took on responsibility for these tasks on definite days.

Everyone had his or her own task. The work problem was a major one, as there were a large number of young children. School classes were carried on in an abbreviated forms and considerable time was needed by adults, for teaching classes.

In the same way, several adults had to give considerable time to the oversight of wardrobes, particularly as so much of the clothing was in a bad state and would normally have been replaced.

The kitchens were supplied with stoves intended for family use, but in two or three of the houses a second stove was obtained. However, the cooking of the food required real planning. The kitchens were equipped with utensils brought to the camp by the internees and by utensils bought or improvised. By the time the camp was moved to Weihsien most kitchens were well supplied.

All preparations, cooking, and serving of the food was done by the women of the camp who were divided into groups which did cooking, dishwashing, and house cleaning in rotation. Each of the houses had its own kitchen, and in most of them the meals served were ample, nourishing, well-balanced and appetizing.

Aside from supplies brought into the camp by internees nearly all food was purchased directly from local merchants, who secured passes to enter the camp from the Japanese authorities. At first they came in at any time without permission, but after Jan, 1943, they were always accompanied by guards who checked the items with the invoices.

Prices were higher than market prices but through competition, checking with Chinese friends and the real cooperation of the Chief of the Japanese Consular Police, who were able to keep them within reason. It is worth noting that on one occasion when we were overcharged the chief of police forced a refund. When one contractor gave us bread that would not keep 24 hours without souring the Chief of Japanese Consular Police changed the contractor and severely warned all contractors.

At all times we were able to secure on the market ample supplies of beef, pork, fish (in season), cereals, peanuts, vegetables, and fruits. Chicken was at times as cheap as beef and afforded a welcome change in diet. Bread was secured at first from local bakeries, but as local supplies of flour ran low it deteriorated in quality and increased in price. Later when the Japanese sold us ample quantities of second grade flour, we contracted with local bakeries to give us 60 pounds of bread per bag of flour weighing 49 pounds at a cost of FRB$23, per bag equivalent to US$3.68. Usually we got very good bread. Plentiful supplies of second grade milk could be obtained from the local dairy. All milk was boiled before use. Milk was apportioned in the various houses in different ways. Considerable milk, butter, and cheese were purchased by individuals.

From October 29, 1942, until January 27, 1943, food was purchased with the internees' own personal funds. At the end of January the Japanese military authorities undertook to provide each internee with a sum of FRB$4.00, the equivalent of US$00.64, per person per day. Flour, sugar, corn meal, some rice and fuel, were sent in by the authorities and the cost of these commodities was deducted from the amount provided for the support. After the Japanese arranged for the feeding, Chinese compradors (under Japanese oversight) were allowed to come in and take orders from the housekeepers. The ladies in charge displayed a great deal of ingenuity in making the money stretch over the need and in making the food appetizing. The amount of sugar received was rationed to one pound per person per month. In some cases no sugar was used on the table and this sugar was used to make jams and marmalade for use on the bread.

Certain supplementary purchases could be made through the compradors for people who required special or extra food ― such as liver (for those on liver diet) ― and extra fruit and eggs. Soap was very expensive, but toward the end of the internment the Japanese authorities furnished both toilet and laundry soap at nominal prices; viz: two cakes toilet and two pieces laundry soap (small) for each person, at 25cents per cake. As Chefoo is a fruit-growing district, fruits of most kinds were usually procurable; also a good variety of vegetables could be secured. These were fairly good; but not the usual best quality as our buying was limited to the compradors who were allowed in and who, therefore, were largely in control of price and quality.

No comfort money was taken or received by the C.I.M. group at Chefoo, its own personal funds being used for any extras that were obtained. Upon arrival at Weihsien, those C.I.M. members who were listed for repatriation were told that they must accept comfort money for August and September, but when the group reached Shanghai it was told that this money was not forthcoming, although receipts for the money had already been signed at Weihsien.

RELIEF SUPPLIES

No clothing or shoes of any kind were sent in, nor were any gift parcels brought in or received.

PURCHASES WITH OWN FUNDS

Practically no restraint was laid upon the internees in the purchasing of food, clothing, drugs, etc., with their own money. Ladies and men's tailors, shoemaker and a laundryman had passes for free entry into camp, although after May they had to be accompanied by a guard. A man selling fresh fruit was allowed in every two, or three days in the summer. No clothing was supplied to the internees by the Japanese at any time.

From October 29, 1942, the first day of internment of the group until January 27, 1943, the internees had to support themselves. By January 27, less than half of the members of houses Nos. 1, 2, and 3 were able to pay the assessments.

At this time they owed the food merchants, carpenter and blacksmith considerable sums of money. After the Japanese took over our support ― and not until then, Mr. Egger, the Swiss Representative, paid one month's relief, and started to pay comfort money as from December 1, 1942. With these funds in hand, all internees with one exception were able to pay up all back assessments. Beginning with January 27, 1943 the Japanese paid us more or less regularly FRB$4.00, equivalent to US$0.64 per person per day to cover all expenses: food, light, heat, repairs, replacements, hospitalization, etc. After March 1943, they sold the internees one half bag of flour and one pound of sugar per-person per-month and later added soap, all of which were sold at very, reasonable prices.

VII -

MEDICAL AND DENTAL CARE.

Availability of physicians and specialists. If Japanese physicians assigned to camp, their professional ability and training. Hospitalization outside camp, whether in occidental or oriental hospitals, quality of treatment and care. Who pays fees?

Officially the medical care of the internees was in charge of the Japanese Public Health Doctor of Chefoo, who before the war had been friendly with the doctors of the mission hospital. As he was very busy he asked the interned medical missionaries to care for the sick and report cases of illness to him. He visited the camp when called and at other irregular intervals, sending internees needing hospital clinic treatment or hospitalization to the Temple Hill Hospital two blocks away. This hospital though nominally under Japanese supervision, was staffed by four Chinese doctors and the Chinese nurses; both graduates and students, who had been there when the hospital was under the mission control. They were all well qualified to treat and nurse the internees. Most of the time the four mission doctors in the camp accompanied their patients to the Hospital but during the last two or three months this privilege was denied with a resultant interruption in the close coordination of medical treatment.

During the latter part of the internment, a Japanese doctor made weekly visits and consulted with our doctors about health, and in a few cases made personal examinations. The whole group was vaccinated, and inoculated against cholera, and before travelling were inoculated against typhoid fever. In a few cases, patients who needed special nursing and diet were treated and cared for. In Temple Hill Hospital, which was adjacent to the camp, one maternity case, several dysentery cases, blood tests, and similar treatment? One patient, who needed special lung deflation, was given treatment from time to time in Temple Hill Hospital, and later in the Japanese Hospital in the city where the necessary treatment could be secured.

VIII -

SUPERVISION AND INSPECTION

Swiss Government Officials.

International Red Cross.

Vatican delegates.

Local relief societies.

Are internees permitted to speak to Swiss representatives without witnesses present? Are local residents permitted or willing to visit internees? Presentations taken by Japanese during such visits.

Mr. V. E. Egger, the Swiss Representative of American and British interests in Shantung, with Head Office at Tsingtao, was in Chefoo on the day of internment and was notified by the American Relief Committee of the concentration. He was present at the camp when the internees were being assembled and he did what he could for the internees, but was unable to alter the plan of the Japanese for the assembly, nor get any concessions for necessary baggage or equipment. He was allowed to come into the camp but was watched closely by a military guard at all times. Mr. Egger returned to camp from time to time to supply the internees with comfort money, give information and get data regarding repatriation. He helped materially in getting permission for individuals in camp to return home for clothing, bedding, etc., that might still be in their home, which in nearly every instance were found to have been looted. On nearly every occasion when he came to camp he was supervised by a guard who understood English, and when thus escorted he was, not permitted to hold private conversations with any of the internees. At times the supervisions were not rigid and on one occasion he was permitted by the Chief of the Guard to have lunch with the internees without a guard.

One German family in Chefoo was very friendly with the internees and rendered valuable assistance in procuring food and clothing for many from the local market. Chinese friends and servants were permitted to talk with the internees at the gate until May, 1943, when the Japanese attempted to cut the camps off from all local contact both foreign and Chinese. Until that time the internees were permitted to have Chinese servants outside the camps who would purchase special food in the market, and who were permitted to collect and return laundry each week. Most off these conversations were supervised by the local Chinese Police who were very friendly when the Japanese were not present.

At no time was the Chefoo camp visited by a representative of the International Red Cross, except by Mr. Egger, the Swiss Representative. Likewise the camp was not visited by any Vatican Delegate or any representative of local relief societies.

IX -

WELFARE AND RECREATION.

Facilities for recreation. Comfort allowances. Personal funds (loans etc.). Passes and temporary releases. For what purposes issued and to what extent. Package lines. "Vacations".

No facilities for recreation of any kind were provided by the Japanese authorities. Courts for deck tennis were made in the gardens of each of the three groups, and group No. 3 had a regulation tennis court which was used for tennis, hockey, and other games. Additional sports and garden equipment was promised by the Japanese Consul, but this never materialized. Other forms of entertainment and amusement were organized in the various houses by the internees. Plays were written and produced, lectures were given, and two orchestras were organized. Courses of study for the community children were given in the various houses until about June when permission was given for them to attend the classes of the China Inland Mission School, in No. 3 compound. Courses of study for adults in home nursing, cooking, and modern languages proved very popular.

The internees were fortunate in having a goodly number of books in the private libraries of the homes occupied by the camp, which were freely used by all. After March, 1943, the various houses were supplied with copies of the Peking Chronicle (later charged to the account of each house) which came with fair regularity. No other papers or periodicals came into camp.

In connection with the schools, a series of lectures and concerts were given by internees, (very informally) but no inter-compound activities were permitted. On Sundays two services were held regularly by each group. For these, detailed notes of the addresses given had to be submitted to the Japanese authorities several days before the Sunday. The Japanese had to approve these notes, but no case where such notes were not approved is recalled. On one or two special days a very few selected persons were permitted to come from one compound to the other in order to take part in the program.

Passes and Vacations.

No vacations were suggested or allowed. During the first few months of internment passes were issued by the military authorities, allowing some internees to return home to get clothing, bedding, coal, and household utensils. Some were able to get essentials but many found their homes already badly looted. Most internees were allowed to make several such trips. Mr. Paradissis (a Greek) and his sister-in-law were given permission once each month to return to their home where Mrs. Paradissis, their invalid, daughter and elderly grandmother were confined. Passes were issued on request to visit the dentist. Internees were given passes to visit the other two groups in the Chefoo camp about once in two weeks. Usually passes could be obtained for particular cases to attend the Out Patient Department of the hospital.

The medical committee of the internees held an emergency pass to the hospital in case of accident or serious illness. All visits outside the camp with passes were made under, guard.

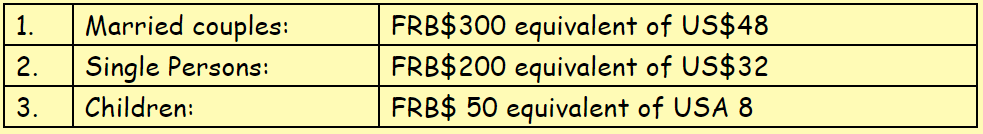

Comfort Allowances and Personal Funds.

Up to October 29, 1942, the initial date of internment in Chefoo, money for the maintenance of Americans and allied nationals in Chefoo with the exception of the China Inland Mission group was provided from a fund of FRB$25,000 equivalent to US$4,000 which the Japanese Consulate deposited with the Yokohama Specie Bank in Chefoo. Periodically beginning with the month of January, 1942, the Japanese Consul paid over to the American Mutual Aid Committee and to the British Mutual Aid Committee in cash withdrawn from the fund in the Yokohama Specie Bank the amounts indicated by the two committees, as required for the living expenses, of the nationals whose names were submitted with the amounts required for each.

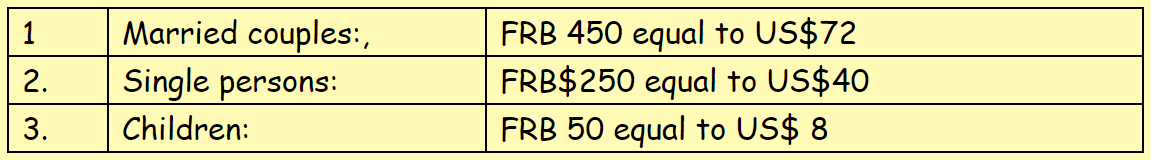

The two committees then distributed the cash to their nationals on the following schedule:

Following this schedule, payments were made on February 17, 1942, for the months of January and February. Similar payments were made in March, April, and May, 1942, when the original allotment of FRB$25,000 set aside for relief by the Japanese was exhausted.

No information was given by the Japanese to the Committees in regard to future repayment.

A delay occurred in the advancing of relief funds by the Japanese following the exhaustion of the FRB$25,000 in May, 1942. Negotiations which contemplated that the Swiss Consul in Tsingtao would take over the matter of relief funds for American and allied nationals in Chefoo failed for lack of Japanese assent thereto. However, after further negotiation and much urging, the Japanese advanced additional funds for June and later for July and August, 1942. These payments were greatly delayed, that for June being made in July, and that for July and August being made in September. No further relief was paid by the Japanese authorities.

When the internees were placed in the camp on October 29, 1942, no relief funds for the months of September and October, 1942, had been given to them from any source. The internees maintained themselves thereafter until January 27, 1943, when the daily allowance of FRB$4.00 (U.S. $O.64) was provided by the Japanese. However, in January, 1943, through the good offices of the Swiss Consulate in Tsingtao the internees were granted relief allowances for the first full month of internment, i.e. November, 1942, as follows:

For the four months following November, 1942, the Swiss Consul in January, 1943, then provided the internees with "Comfort Money" on the basis of FRB$50, (US$8) .per person per month. Thereafter the "Comfort Money", was paid regularly each month up through May, 1943. In June and July, 1943, the "Comfort Allowance" was increased to FRB$150 ($24.00 U.S.) per person. The "Comfort Allowances" for the months of August and September were not paid to the internees until after their transfer to the Weihsien Camp. Those of the internees, however, who were to be repatriated in 1943, requested that their August and September "Comfort Allowance" be remitted by the Japanese at Weihsien in part to the St. John's Camp at Shanghai, where they were to be lodged temporarily prior to their embarkation, and in part to repatriation vessel "Teia Maru". They signed receipts at Weihsien for the August and September allowances, but in fact only that part remitted to them at St. John's Camp in Shanghai was received; the portion directed for them on board the vessel was never received.

Those nationals attached to the China Inland Mission were offered the same amount in comfort allowances and relief allowances, but declined to accept the money on any basis, inasmuch as it is the policy of the China Inland Mission and the members thereof not to obligate themselves financially.

X - COMMUNICATIONS

How often letters and cards may be sent by internees; restrictions on length and contents. Regularity of receipt of mail. Transit time. Particularly important are facts which may be quoted indicating where, delays may have occurred.

The internees in Chefoo were permitted to send one Red Cross letter per person per month. These were sent out with Mr. Egger of the Swiss Consulate at Tsingtao, none being sent directly through the Japanese. Mr. Egger brought a small number of Red Cross letters into camp, and occasionally one would be brought in by a Japanese Consular representative. Later it was required that a list be prepared by each internee of those to whom they would wish to send letters and from whom they might expect letters. 100 word letters were permitted to be sent, after censoring and rewriting, to those on this list. No other provision for communications was provided. Descriptions of the camp, location, number of internees, living conditions and certain activities were the chief items deleted by the Sensor.

Letters could be sent by the International Red Cross, but these, were very long in coming. For instance, Red Cross letters mailed in U.S.A. in November and December, 1942, reached camp in Weihsien on September 14, 1943. A card definitely stamped as received in Chefoo by the Post Office in February, was not delivered until four months later, and this was merely a greeting card with no personal message on it.

Until May, 1943, when the Japanese became aware of this avenue of communication, English letters in Chinese envelopes and, addressed in Chinese were frequently delivered surreptitiously by the Chinese Postman, and replies were sent through similar channels. This constituted our main contact with Free China and our home country.

XI - LABOR

What kind and where performed. Voluntary or paid for; mode of payment, that is money or kind, food, etc. If wages paid for with money, what could be purchased? What compensation to those who were injured during course of labour.

All work was done by internees. Pumping water, building fires in kitchen and rooms, all cooking and preparing of foods, dish-washing, laundry (with a few exceptions, large pieces could be sent out to Chinese laundries, but these were subject to very close inspection and the work was not very satisfactory).

Repairs (except a few repairs of pumps and plumbing, which required iron workers) were done by our internees, including making some furniture. A few carts of water were brought in daily by coolies to supplement that pumped from the wells, and coolies were provided by municipal authorities to remove the night soil. Aside from these, no help was permitted. For a time tailors and shoemakers were allowed in to take orders for new shoes and for clothes. Also, a few amahs came and took away some mending and sewing.

The internees were not asked to do any labour outside the camp, but all the labour inside was performed by them. Labour groups composed of men, women, and the older children were appointed by the house executive committees and their work designated. Every internee except the aged, sick and very young was in one or more labour groups. No servants were allowed by the Japanese, so the question of pay was not considered.

XII - PUNISHMENT.

Penalties prescribed for Americans, particularly for attempts to escape. What proceedings for accused. What disciplinary measures rather than penalties prescribed by quanjudicial proceedings.

No occasions requiring punishment or discipline arose. On one occasion, long before internment, two boys wandered over the bluff and came upon some fortified place. They were held overnight but were not mistreated and were discharged the following morning.

When the Japanese Consul took over charge of the camp from the Military, the Chief of the Japanese Consular Police was given charge of the camps. This was a fortunate choice for all internees as this man really had the interests of the camps at heart. He was limited in his powers, but he did all that he could for us. He won the respect and admiration of all who dealt with him.

XIII - SUPPLIES FOR INTERNEES.

What supplies sent by Red Cross or other organizations reached camps; nature of supplies, date of arrival, method of distribution. What possessions were taken away from internees without receipts being given?

No Red Cross or other relief supplies reached the Chefoo Camp.

When the internees left their homes they were allowed to take very limited amounts of necessities and no receipts were given for the things left in their homes. All keys had to be surrendered to the Military. Looting started in most of the houses at once. All bicycles in the camp were confiscated in March, 1943, when the Japanese Consular Police took over the guarding of the camp. No receipts were given.

Musical instruments, furniture, bicycles (quite a number owned by the school-boys), books, cameras, radios, wall pictures, were taken and no receipts were given.

There were at least 500 beds left at the compound of the China Inland Mission in Chefoo at the time when members of that mission were interned in October, 1942. These missionaries were not allowed to take any of the beds to the internment camp at Chefoo and consequently suffered considerable discomfort. No beds were available during the entire period of internment in Chefoo from October, 1942, to September, 1943, except those found on the promises at the Temple Hill Compounds. These premises were simply the simple foreign style one family residences of missionaries. The morning the internees left the Chefoo Camp on their journey to Weihsien in September, 1943, Japanese trunks were waiting at the gates of the camp to remove equipment which the Japanese would not permit internees to take or which had to be abandoned.

The worst crime was the wholesale looting of the baggage of the internees during the transfer to Weihsien and while under the care of the Japanese. The looters seemed to want especially man's winter clothing, shoes, and bedding, though women's clothing was also taken. Evidently several pieces were opened at a time and a choice made, for in repacking the rejected articles they often returned them to the wrong pieces of baggage. Some lost all their winter clothing, a very serious loss. Even the baggage of some repatriates was looted between Chefoo and the ship at Shanghai.

XIV -

PERSONAL TREATMENT OF INTERNEES.

In general, it is desired to know whether any internees have been exposed to violence, insult or public curiosity.

With but one exception, no one was exposed to violence, insult, or public curiosity. On one occasion when a group of men from the camp were taken to the beach to fill bags with sand to be brought to the camp for air-raid precautions, the guards accompanying this group left their revolvers at headquarters and were armed only with the customary short sword.

One internee, a widow of a British missionary, who herself had a Chinese mother, and who had many contacts among the local Chinese, was discovered to have received some letters from Chinese friends and was taken over to the guards for questioning during which she was struck by one with a cane. She suffered no more than the nervous reaction of the incident.

In the beginning of the internment, the camps were under the charge of the military, and there was little order or system in the oversight. Later on the Consular authorities took over this work and responsibility. The oversight was more strict, but the methods were more regular. Compound gates were kept locked and roll call was held morning and evening. With a few exceptions ― several aged people, one invalid, and a new born babe ― all were required to appear at roll call.

***