THE BOXER REBELLION

Future Chinese officers at school in Tientsin.

There were reports of Imperial troops joining the rebels.

THE BOXER REBELLION

December 1999, By Norman Cliff

This month sees the centenary of one of the most famous times of martyrdom in China ...

Mildred Cable once observed: 'The year 1900 holds the same significance as does the Flood in Old Testament chronology. All China mission history dates before or after 1900'

Missions in China had been going for six decades of the 19th century when the Boxer Rising took place. There were 85,000 Chinese Christians in some 60 Protestant societies, and church buildings and institutions were just beginning to reach a fraction of the population.

The Rev. Sidney Brooks, an SPG* missionary, 24 years old, had been trained for his future work at St. Augustine's College in Canterbury. After his arrival in north China, he had a dream that he was back at his college looking on the cloistered wall of the Memorial Chapel at the list of graduates who had been martyred on the various mission fields. As he gazed at the space under the last name on the list, his own name began to appear.

On the last day of 1899, Brooks had dinner with his sister in Taian, Shandong. Returning by foot to his station at Pingyin at night-time he was waylaid by a band of young toughs. He tried to run ahead of them but men on horseback chased after him, and he was beheaded. He was the first Boxer martyr.

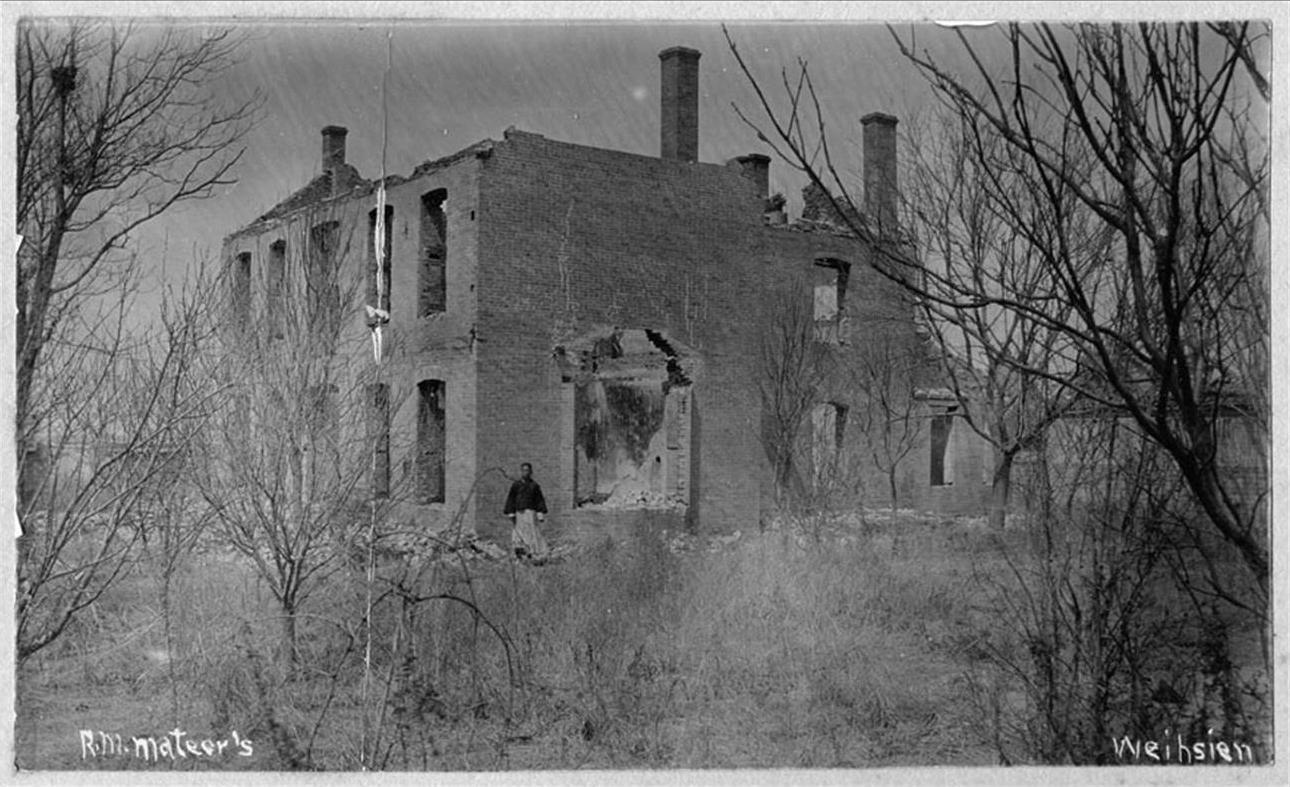

Destruction

The Boxers, teenage boys wearing red sashes, worked their way from Shandong north China to Hebei, Shanxi, Manchuria and Mongolia, killing Christians and destroying Christian churches and homes wherever they went. Large-scale massacres took place at Baoding in Hebei .and at Taiyuan in Shanxi. At the latter town, no fewer than 77 Christians were executed in front of the provincial governor, Yu Xian. Two of the missionaries preached to the onlookers while they were awaiting execution.

In the ten, months of the Rising, 188 Protestant, missionaries (including children) were killed, 115 of this number relating to the China Inland Mission and the Christian & Missionary Alliance. 47 Catholic missionaries were killed. Probably as many as 30,000 Chinese Christians were massacred. Thousands more were injured or had their homes and farms burned down.

In Beijing , diplomats, missionaries and journalists were under siege in the Legation Quarter for eight weeks, from mid-June to mid-August 1900. They were finally rescued by an international army from nearby Tianjin. 1,000 foreigners and 3,000 Chinese had survived on limited quantities of rice and horseflesh. Regrettably the Allied forces looted the ancient City of some of its historic treasures.

Causes of the rebellion

What were the causes of this violent outburst of murder and destruction? The Boxer Rising is widely thought of as a purely anti-Christian drive to challenge the progress which missions were making among the nation's populace. But the causes go far deeper than that.

First, there was the religious and missionary problem. Both Protestant and Catholic missionaries had committed acts of cultural arrogance: There had been cases where Protestant missionaries had invaded temples during religious ceremonies and denounced the worshippers as idolaters, and when given temporary accommodation in a temple, dismantled the shrine and buried the idols.

But the policies of Roman Catholic missions were considerably more aggressive. For example, in Shandong, they had taken undue advantage of the privileges of extra-territoriality, which gave foreign consuls jurisdiction over their own nationals and also over the Christian converts. By admitting whole clans and villages into the church, people of bad character escaped lawsuits and discipline. This had caused much bad feeling among the populace. French historian Henri Cordier has claimed that this was the principal cause of the Boxer Rebellion.

In addition to the religious factor, there was the political one. Britain, France, Germany, Portugal and Japan had been competing for spheres of influence in China, and the 'cutting of the melon' had left the nation feeling exposed to foreign control. J. O'Connor states: 'China felt itself to he in the position of a corpse laid out on the international dissecting table.'

Economics & the weather

Then there was the important economic factor. Conditions of drought, famine and destitution had worsened. Unemployment was rising steadily. Local industries had been adversely affected by the importation of foreign cotton and oils. Carters and boatmen had been thrown out of work through the use of railways and ships. There had been repeated crop failure, and the drought was attributed to the anger of the gods at the disturbance of 'feng shui'.** It was alleged that German mining and railroad building activities had disturbed the ancestral graves. Prior to the drought, there had been an excess of rain in 1898. The breaking of the banks of the Yellow River, 'China's Sorrow', resulted in death or financial ruin to millions of peasants.

Fourthly, there were social problems. Chinese Christians were seen as inherently suspect because they had loyalties outside the village. Under the Unequal Treaties, they could go to the missionaries for assistance in village disputes and court cases. They absented themselves from the processions in honour of Chinese deities. Their refusal to contribute towards the upkeep of shrines and temples, placed a heavier financial burden on others. This defiance of tradition gave rise to feelings of anger and indignation.

After the Rising

The Boxer Protocol of 1901 imposed some heavy indemnities and punishments on China. Ten high officials were executed and 100 others punished, and US $333 million was to be paid to Western organisations over a period of 40 years. Most missionary societies refused to accept any compensation for loss of life or property. Some accepted funds for the rebuilding of churches and schools. Missionaries had the task of trying to restrict unreasonable claims by their Chinese Christians.

After the Rising, there was the enormous task of reconstruction and rebuilding of churches and institutions after the havoc and destruction. The relatively young church had lost many members in the slaughter of Christians. Some who survived left the church altogether, afraid of further crises in the future. But in spite of losses in membership, there was unprecedented growth in the opening years of the new century. For example, the British Baptists lost 700, but by 1910 had more than recovered this number.

But what of the Christians who had recanted during the rebellion? Dr. H.R. Williamson describes the experience of the British Baptists, which was typical of that in other societies. 'When the missionaries came face to face with their brethren, and realised more clearly the nature and circumstances of the ordeal through which they had passed, the 'warmth within the heart' melted 'the freezing reason's colder part' ...in most cases, public confession of recantation was required; periods of discipline were imposed, and the great majority were eventually restored to the fellowship of the church.'

A new age

After the Boxer Rising, China moved into a new age. The old civilisation and its outdated methods collapsed, and the nation was determined to adopt Western technology and thinking. There was a complete reorganisation of government departments, and of the Army and Navy along Western lines. The Manchu Emperor abdicated, and at last the Chinese were in control of their own land. In 1912, the Chinese Republic was proclaimed.

The youth of China were now eager to adopt Western ways and thinking. This included learning about Christianity. The missionaries found more doors open than they could manage. With many wishing to join the churches, it was difficult to identify which applicants were doing something 'fashionable' and which were genuinely wishing to follow Christ. All the societies, in addition to rebuilding past institutions, enlarged their operations to cater for the new growth of interest in Christianity. K.S. Latourette states that whereas in 1898 there were 80,682 Protestant Christians in China, by 1915 there were 268,652. The heyday of missions was to be in the period from 1900 to the 1930s.

At the time of the massacres, Hudson Taylor, at the head of the mission which had lost the most missionaries, was convalescing in Davos, Switzerland, incapacitated after a period of strain and overwork. The tragic news from China was arriving in a succession of telegrams. Jennie Taylor tried to break the news in gentle instalments to her invalid husband. Bowled over from the heavy losses of workers, Taylor could only say: 'I cannot read, I cannot think, I cannot even pray. But I can trust.'

Four months after the rebellion was over, Hudson Taylor wrote: 'God has made no mistake in what he has permitted. His interest in the spread of Christ's kingdom is greater than ours. Our hearts cannot but ache for the places left empty and for the shepherdless Christians . . . We trust our omnipotent Lord, and are sure that his tender heart would not have allowed such trials had there

been any easier way of securing the fuller triumphs of the gospel.'

* Society for the Propagation of the Gospel --- now: the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

** FENG SHUI is the science of wind and water on good luck.

Dr. Norman H. Cliff is a retired minister of the United Reformed Church.

His parents worked in the China Inland Mission, as did his maternal grandparents and great-grandparents (Broomhalls).

[click here]