STARS IN THE SKY

by Father Patrick J. Scanlan

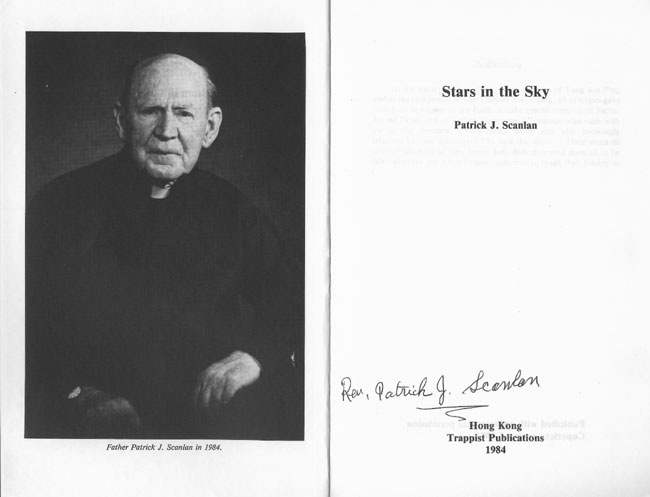

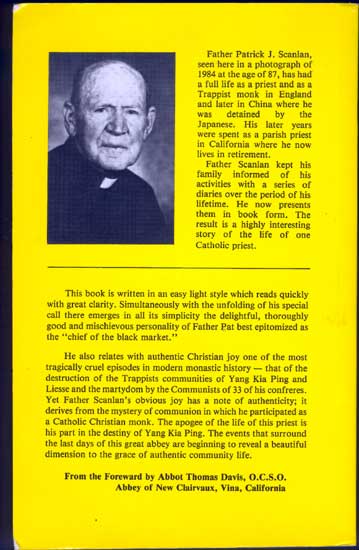

Father Patrick J. Scanlan, seen here in a photograph of 1984 at the age of 87, has had a full life as a priest and as a Trappist monk in England and later in China where he was detained by the Japanese. His later years were spent as a parish priest in California where he now lives in retirement.

Father Scanlan kept his family informed of his activities with a series of diaries over the period of his lifetime. He now presents them in book form. The result is a highly interesting story of the life of one Catholic priest.

This book is written in an easy light style which reads quickly with great clarity. Simultaneously with the unfolding of his special call there emerges in all its simplicity the delightful, thoroughly good and mischievous personality of Father Pat best epitomized as the "chief of the black market."

He also relates with authentic Christian joy one of the most tragically cruel episodes in modern monastic history ― that of the destruction of the Trappists communities of Yang Kia Ping and Liesse and the martyrdom by the Communists of 33 of his confrères. Yet Father Scanlan's obvious joy has a note of authenticity; it derives from the mystery of communion in which he participated as a Catholic Christian monk. The apogee of the life of this priest is his part in the destiny of Yang Kia Ping. The events that surround the last days of this great abbey are beginning to reveal a beautiful dimension to the grace of authentic community life.

From the Foreword by Abbot Thomas Davis, O.C.S.O. Abbey of New Clairvaux, Vina, California

STARS IN THE SKY

By Father Patrick J. Scanlan

excerpt ...

DIARY 6

OUR LONG INTERNMENT

After our dinner on March 17, 1943, the Priests and students of Yang Kia Ping were reading quietly in the study room. Suddenly from outside there arose the murmur of many voices, followed by the trampling of heavy military boots, as a company of Japanese soldiers swarmed through the corridors and into the yard. The Canadian, the Dutchman, and I were immediately summoned and told to be ready to leave in half an hour for an internment camp.

Three soldiers were told to follow us. If one of us seemed to be delaying, the soldier in charge of him tapped him on the rump with the flat side of his bayonet, saying in Chinese, "Kuai, kuai dee" (Hurry up!). Chinese troops were in force in the hills, and the Japanese wished to get away as soon as possible.

In the midst of the soldiers, we walked through the Abbey gates, while the whole Community, assembled on either side, looked on in silence. Three workmen carried our bags and bedding. As we passed around the mountain path, Father L'Heureux said to me, "They are taking us on the feast of your patron Saint." It was Saint Patrick's Day, and Father had many times heard the story of the dilemma of my birth.

At the Japanese outpost, we found two lorries waiting. We climbed in, and the drivers started at once. Father Drost was in one lorry with half of the soldiers; Father L'Heureux and I were in the other. It was about 3:00 P.M. For hours the trucks sped along, bumping over the rough mountain roads. Unlike the day we were taken to Hwailai, Father L'Heureux did not speak to the soldiers, nor did they speak much among themselves, but as on that day, all the time they clutched their rifles. I had refrained from eating before I left the Abbey, and was not sick this time in the lorry. I was very cold, though. Darkness set in, and above us the stars shone down from the blue sky. They seemed to be saying, "Do not be troubled; all this will pass."

At about ten o'clock, we reached a railway station, and we three Priests with an officer and two soldiers climbed stiffly down from the lorries. Hardly a word was spoken. We had to wait over an hour for the train, and we were very tired. The officer and the soldiers left us in a small waiting room, where a kong, well warmed by the fire burning underneath, looked very inviting. Father L'Heureux, taught by the experience of his missionary days, advised us not to lie down, saying that they always avoided these public kongs when travelling, because there were usually lice on them. He sat up stoically, with his shoulder propped against the wall. We were worn out, and I lay back for a few minutes and then sat up again. Father Drost looked exhausted ― we had had nothing to eat; it was long past our bedtime, and the many hours' drive in the springless lorries had been very trying. Even the soldiers seemed tired. For a time Father Drost leaned against the wall, but finally he stretched out full-length on the kong and stayed there until the officer came for us. That rest on the kong was to have for Father Drost very serious consequences.

After about half an hour on the train, we reached the town of Suan Hua Fu, and walked to the soldiers' quarters. A pot of sukiyaki (a Japanese dish of meat and vegetables combined) was cooking on a fire placed on the table, and at the officer's invitation we helped ourselves with the chopsticks and drank a little sake (Japanese rice wine). When the clock pointed to midnight, we stood up, and they showed us our rooms, where we rested well, sleeping far into the morning. Near midday, the officer took us to the Seminary, where the Chinese Bishop, Monsignor Chang, lived with the students and their professors, the four Belgian Priests who were also to be interned. Students from the Seminary served our Masses, then we joined the Bishop and Priests at dinner. Next day the officer came, and took the seven of us to the train, and after an hour we reached Kalgan, the capital of Mongolia. There in the church compound we found a crowd of Belgian Scheut missionaries assembled for the same purpose as ourselves.

We soon met Father Joseph Nuyts, who was both an Apostolic Delegate and the Scheut Provincial of Siwanze. Our Abbey had already found in him a most faithful and reliable bulwark in our troubles. Now we were to have never-to-be-forgotten proofs of his kindness, sympathy, and help. From that day, through all the time of our forced inactivity, he remained our benefactor, a kind adviser, and most reliable friend. He treated us as his own. I refrain from going into details, much as I would like to.

During the afternoon, more priests arrived on horseback and in lorries. They were all strong men; some of them looked like giants, as they were wrapped in great sheepskin coats, and wore fur hats, the sides of which stuck out like wings. A load of Belgian Sisters also drove up ― the Canonesses of Saint Augustine. They were sitting on the floor of the lorry. The Priests raised a cheer and hastened to help them alight. They all looked strong, healthy sisters, and they needed to be, for Mongolia, with its long, frozen winter, is a very difficult mission.

Next morning, the Japanese marched us to the railway station. There we saw a trainload of more Scheut missionaries, Priests, and Sisters drawn up at the platform. They were strong and cheerful men and women, whose splendid physique made it possible for them to carry on their evangelization of the people, despite the great winter cold; despite, too, the sandy desert with its veering winds, its shifting sand dunes, and those yellow sandstorms that surprise the traveler on the way, enveloping him in darkness that may last for days, and taking toll of many a human life. As we drew close, their hands fluttered through the windows in welcome. All these Priests and Sisters felt keenly their being torn away from their people, amongst whom they were doing so well, but now cheerfulness was the order of the day, the watchword for us all.

When all were packed into the train, we started for Peiping. There were over two hundred in all, if we include in the count the few Protestant missionaries with their families and the lay foreigners. A few Japanese officers and soldiers accompanied us, but they left us to ourselves and were seldom seen.

The Japanese said that we must provide our own food until we reached the camp. We three from Yang Kia Ping had brought only a few loaves of bread and some bottles of altar wine, hence we would have been hungry on the long train journey were it not for Father Nuyts. When he and another Scheut Father went along the corridor with large baskets, tossing out sandwiches, the sausages, the cakes and the tea, we received the same as the rest. "Distribution was made to each according as he had need."

At Peiping we changed trains; it was then getting dark. We slept as well as we could, and it was still night when the train ran through Tientsin. Then came the long run south to Tsinan, the capital of the province of Shantung. From there we turned east to the stopping place, Weihsien. From the Weihsien station, Japanese lorries carried us to the camp some miles away. The journey from Kalgan had taken a little over thirty hours.

The Japanese guards stationed at the camp met us at the gate and herded us into a large field nearby. We soon learned its name ― the Sports Field. There we were formed into lines, and every man answered to his name, called out by the officer who had taken us from Yang Kia Ping, and who was in charge of the train from Kalgan. Then the governor of the camp, or "commandant," took over. He spoke English very well. He had been the Japanese Consul at Honolulu for several years. He passed among the priests and asked for an Englishman, and I was pointed out. He handed me a long printed paper, and said he wished me to read it out to the newcomers. Most of the Priests knew some English; though very few were able to understand it all. I glanced over the two sheets, then I was helped on to a table. The Priests crowded around and listened intently to "The Rules of the Camp for Enemy Nationals."

These rules regulated our whole day, the hours for rising and going to bed, the times for meals and for lights out at night.

Committees were to be formed, for we were to be self-governing, under Japanese surveillance. No intercourse was allowed with the Chinese, either outside or inside the camp. All money was to be handed in, and we were to receive a monthly allowance of 200 Chinese dollars. We were to buy from the camp canteen only, and we had to do all the work necessary for the cleanliness and upkeep of the camp, and so forth.

When I had finished the reading and climbed down, the Governor thanked me and motioned me to keep the paper. He had reason to be pleased, for I had given out its contents with as grand a voice as I could. I enjoyed reading out the rules to these tough missionaries, and when I glanced occasionally, I saw many a grin on their faces, as they listened to my eloquence.

Shortly after I had finished, the lorries arrived with our luggage, and by the time each had sorted out his own, it was quite dark, and we were ready for our first Japanese-provided meal. Alas, it was bread and tea! Ladies from among the few hundred internees already there served it and were as nice as they could be. They said many a "We're sorry!" when refusing the requests for more, but they added a note of hope ― "You'll get more tomorrow." More what? More bread and tea!

That and the following night we slept on the floor. On the third day, almost all the internees from North China had arrived in the camp, and it was possible to assign to different groups the quarters that their numbers called for. Father L'Heureux, Father Drost, and I were given our permanent abode, a small room near the end of a long building that stretched down the southeast side of the enclosure wall. Two Belgian Trappists, from the Monastery of Our Lady of Liesse, near Chengtingfu, were also interned. They occupied the end room. We three had the second room. Our camp life had begun.

I will now attempt to describe the Weihsien Concentration Camp. The Japanese had found a very good place, though it would have had to be about four times as large if we were to live there in accordance with European ideas of hygiene and comfort. It was, or had been, a University, built and run by an American Protestant missionary society.

On the north side were several large two-storied buildings; these had been the residential quarters of the Protestant missionaries and their families. These houses with the adjoining gardens and grounds were now taken over by the Japanese, and were "out of bounds" for the internees.

On the south side, there had been a large and well-equipped three-storied hospital, but this had been plundered and ransacked by the Japanese soldiery to such and extent that it was completely unfit for use. The committee of the internees immediately began to repair it, and after a month of hard work, part of it was ready for use. This hospital saved many lives. We were fortunate, too, in having several skilled, doctors among the internees, also some skilled nurses among the Sisters.

On the east side, not far from the entrance gate, where the Japanese guards watched by day and by night, was a large assembly hall for the students. This proved a great boon for the internees. When we used this hall for amusement, we called it The Hall; when it was used for Divine Service, by common consent of all denominations, it was known as The Church. To the northeast of this building, there was a large playing field. It soon became popular as the Sports Field, or the Sports Ground. Both these places, the Church Hall and the Sports Field, entered much into the lives of the internees and played a big part in keeping up both morals and morale.

As I said above, our quarters were at the end of the long row of houses by the southeast wall beyond which was a road, and on the other side of the road there were a few Chinese homes. This was to prove very convenient, as you will hear later.

The rest of the space within the walls was built over with a large number of long, low buildings, divided, for the most part, into single or double rooms. These were arranged to form "streets," or "blocks," as we called them. A yard was lying in front of each row of houses, all of which faced the same way. These rooms were occupied by families, or others who could form small groups, such as Father L'Heureux, Father Drost, and myself.

Scattered here and there were a few large two-storied buildings, probably used by the students for their classes. These were occupied by the Sisters, the bachelors and married men whose families were not with them, and the maids ― both "old maids" and girls whose families were not in the camp. These buildings were really no more than dormitories, for each person had no more than a few feet of empty space before his bed.

To the Scheut Fathers, the largest group in the camp, was given one wing of the hospital. Three large low buildings served as refectories. Each had a kitchen attached to it where our meals were prepared. Japanese guards not only passed about through the camp, but they also occupied a three-storied building in our section, and from there they could see over most of the camp. A few soldiers also always watched from lookout points built on the wall, for there were Chinese guerrillas not far away. This wall, built of stone, was about seven feet high, and the space it enclosed comprised five or six acres. This was our camp. It contained over 1,700 internees, of whom about 300 were Priests and 160 were Sisters.

The Japanese left it to the internees themselves to settle on what houses they were to live in. A committee was formed in which the Priests were well represented, and the division, when finally made, gave general satisfaction. Everyone then became busy, fitting up beds and arranging rooms, all providing for themselves what comfort they could. Some had brought much with them, some very little. When we were leaving the Abbey, we had been allowed to take away with us a very limited amount, for there would not have been room in the lorries, already closely packed with soldiers. There was nothing to do but to spread our mattresses on the floor of our room, but after a few days the Scheut Fathers noticed it and gave us three camp beds. They had brought a good supply of useful things with them.

The Priests first thought of providing for their daily Mass. It was not becoming to celebrate in our sleeping rooms unless we were excused by real necessity, so permission was sought, and easily obtained, from the Commandant to put up altars in the hall. Small tables that had been used by the students were plentiful, and we got together about fifty. Some Priests left their things locked up in a corner of the hall; others of us each morning took along what was necessary for saying Mass. After a few minutes of preparation we were ready to start, and when finished, we would stack the tables in a corner out of the way.

We had not been in the camp a week before Father Drost's health began to give us cause for anxiety. Tall and very thin, this earnest young Dutch priest had found the conditions at the Abbey very trying to his delicate constitution; the food especially did not contain sufficient nourishment for him. It was only to be expected that he would be fatigued by the week's strenuous travelling, and also for the few days after our arrival, when we were so busy arranging our new quarters. We thought he would brighten up again when conditions became more settled, but on the contrary, he became worse. He was listless and without energy to do anything, but he kept trying to drag himself about, giving us what help he could. I advised him to lie down, but he would not. Later, he began to rest a little, then would get up and do something. Father L'Heureux spoke to him seriously, and told him he was not doing well in refusing to follow my advice, seeing that I was the senior, but Father Drost answered that he hoped by keeping going, he would shake off his indisposition.

A Sunday morning came, and we saw father preparing to go to the Church for the public Mass ― a high Mass with a long sermon. We begged him to go to bed instead, but he was not willing. He left the Mass rather early, and when Father L'Heureux and I walked down together to our room, we found that he had thrown himself on the bed without taking off his overcoat. We said nothing, but left the room and spoke together in the yard. Father L'Heureux said, "You get Dr. Geens. I'll stay with Father."

I soon found Dr. Geens, a Scheut Father, and a very able doctor who had been in charge of the General Hospital at Ta Tung, in North China. I will add immediately that he was as grand a Priest as he was an excellent doctor. He got his instruments, and we returned to the sick man. Father L'Heureux and I waited outside. Dr. Geens came out with a grave face.

"Your brother," he said, "has typhus. Why did you not call me before? We cannot do much for him; he must just fight it out himself. They seldom recover, especially the young men." He returned with some medicines, and sent two Belgian Sisters to nurse him.

Typhus is a very terrible sickness. Young men, and those the strongest, are its first victims. Father Leyssen, Scheutist, Rector of their major Seminary in Mongolia, wrote an excellent little book, The Cross over China's Wall. On page 71, he writes, "Today nearly 200 graves of Scheut Fathers may be counted in China and Mongolia, and most of them were dug to receive the victims of typhus."

This disease at one time looked as if it would destroy the prosperous Scheut missions in Mongolia, until a professor in Peiping discovered an inoculation that rendered those that received it practically immune from its attack. Typhus is got from the bite of lice, and Father L'Heureux and I always thought that Father Drost got the lice on him the night we waited at the station when we were being taken to the Japanese headquarters at Suan Hua Fu. Father, tired out, had laid back on the kong. That was why I explained those details so minutely.

Doctor Geens told Father Drost of his danger, and the invalid at once sent for his confessor. That night we watched by him in turn. Oh the evening of the following day, as Father Drost continued to sink, he was carried to the hospital where a room had been hastily prepared for him. The hospital was not yet in working order, yet he had every care, Dr. Geens and the Sisters being in constant attendance.

The next evening, Dr. Geens sent me word that Father should be anointed. He was very low; he did not seem to be suffering, but the spark of life in him was very faint. He lay calm and peaceful with a white blanket of the Sisters drawn up around him. He was quite ready to die and seemed to be taking the business of dying with the same quiet willingness as he had done his religious duties and the other events of his life. Being the senior, it was my sad privilege to confer on him the Sacrament of Extreme Unction. Father L'Heureux and the two religious from Our Lady of Joy stood around answering the prayers. Throughout, Father was quite conscious, but very, very low.

After the anointing, we remained in the room, but the Sister on night duty asked us to leave. She said his mind would be more at peace if he were left alone. So, silently, we left the hospital. We did not expect to see him alive again. Dr. Geens and the Sisters had much experience of typhus cases, and they held no hope of his recovery.

Early next morning, Father L'Heureux and I went to the hospital. We met the Sister in the passage near his room. She smiled and whispered, "He took a turn for the better during the night. His temperature is going down."

"Deo Gratias," we both murmured.

From then on the patient never relapsed. Day by day he improved, and after a fortnight he was able to walk back to his room. One of us had nearly dropped out, but we were all together again.

However, Father Drost's sickness was by no means over. He was a very weak man and needed great care for a long time. For six months his complete recovery remained in doubt, and after that he had a long period of convalescence lasting a year or more. Father L'Heureux arranged with Dr. Geens that the Sisters would come to see him daily, but only for a visit. Father himself wished to be the nurse. As a Jesuit he had learned some first aid, and he was very handy with the sick. For months Father L'Heureux looked after Father Drost. At first, it took up all his time, and in order that he might be free, I asked the Internees Labor Bureau not to call on him for any work. After a few months he was given some light work ― helping the ladies to prepare the vegetables.

There were two young French-Canadian Jesuits in the camp, and these were friendly with Father L'Heureux. They often came to our room to see him and occasionally gave him some of the tinned food that they had brought with them from Tientsin. Most of this, Father gave to his patient. It was very welcome too, for the lack of good food certainly retarded Father Drost's recovery.

During Father Drost's sickness we said Mass in our room in order to give our invalid the consolation of hearing Mass and of receiving Holy Communion. After about a month, he was able to say Mass again, first in our room, then one fine morning we took him to the Church. He said a short Mass in black, after which Father L'Heureux took him back to the room. Taught prudence by his grave illness, he now did whatever Father L'Heureux told him. The month of May brought sunshine and warm weather. Sometimes Father Drost sat out in the sun on a folding chair, which a Dutch Father had lent him. When tired, he lay on the bed that Father L'Heureux daily put out in the yard for him. Father L'Heureux had the comfort of seeing his patient slowly, indeed, but surely growing stronger.

Now I will give you a general idea of our camp life, then some details which you will find more interesting. We rose early, at least most of the internees thought so. Soon after sunrise, a man passed through the camp vigorously ringing a large hand bell. Soon after, the Japanese guards went to different parts of the camp for the roll call. This was the big event of the day. Everyone not actually confined to bed by sickness had to be outside his hut, as the guard passed along with a paper in his hand indicating the number of people in each house and in each section. In response to the excited calls of warning of those already in the yard, people who were lovers of the blankets would make a last minute rush when the guards were approaching. A song composed in the camp commemorated it: "Roll call; roll call! The roll call gets you up!"

The next event was breakfast. This usually consisted of bread and tea; later on, the women became very clever at making up a mixture from the scraps left over from the preceding midday meal ― if anything was left over. For the Cistercians bread and tea was the usual morning meal; for most of the people it was a starvation diet.

Almost all had some work assigned to them, and about half an hour after breakfast they went to their various jobs for a couple of hours. Occasionally during this time, especially at the beginning, there was a general roll call. Everyone had to assemble in the Sports Field and line up according to number. Each had his name and number marked on a piece of cloth, and this he had to pin to his coat or dress when going to the roll call. These general roll calls were very trying. Often we had to stand in lines for hours. The guards had difficulty in counting us. They would count the several long lines, compare notes, then count again. The old people and the infirm found the long stand very difficult. Once an old lady fainted. As we got to know our way about, many made small folding chairs which they carried to the Sports Field, and when not actually under inspection sat down. It was during these long roll calls that our Japanese masters came in for a great deal of criticism.

Dinner was at one o'clock, and from all over the camp the people could be seen making their way to the three kitchens. Each carried his own cup or mug, his spoon and fork ― if he happened to have brought them with him to the camp ― and also a plate, or better still, a small bowl or basin in which to receive his portion of food. Some had tiny bowls; others had dishes large enough to hold the portions of many. We brought what we could get.

After dinner, especially when the warm weather set in, most had a sleep for an hour or more. Then work began ― from about half past two until five o'clock. We were determined not to become despondent in our captivity, so we organized games that proved a great help and became very popular in the camp. The games were generally played in the afternoons, and all who could arranged their work so as to be able to attend the games. The players, if unable to finish their work in time, changed hours with others on the same job, or got someone to take their places.

As things settled down, most managed to have tea and something to eat about four o'clock, and for this purpose they took home with them some of the few slices of bread given out at meals. Besides the very modest quantity that could be obtained in the camp canteen, we soon learned to supplement our rations from the bountiful supplies offered by the Chinese outside the wall. This I will tell you about later.

Before six o'clock, all changed their working clothes and again gathered up their utensils and took their places in the long queues in front of the kitchens. This supper was often a disappointment for the provisions given out for it from the store were neither abundant nor certain.

After supper the people amused themselves in various ways until ten o'clock, when the electric lights were switched off in the camp and everyone had to remain indoors. We know it is the usual thing for men and women to give themselves a few hours of relaxation and pleasure in the evenings; the internees did so too, and with the deliberate intention of keeping bright and cheerful, because we were in circumstances in which it would have been easy to lose courage. The leaders did their best to arrange interesting programs to give the internees a few hours’ enjoyment. Concerts, dancing, lectures, gramophone selections, community singing ― all had their turn. The priests played a big part in the drawing up of the amusements program, as they did in organization of sports. In fact, after a few months, the Fathers' concerts on Sunday nights were the most popular event in the camp. People also invited their friends during the interval after supper and whiled away the evening together. Some minutes before ten o'clock the electric light was dipped for a few seconds as a warning. Then there would be a rush to get back to one's house before the lights were turned off ― not only to avoid going home in the dark, but to avoid the guards also.

Before beginning to write more in detail of our camp life, I wish to say that we were not badly treated by the Japanese. The rules of the camp were reasonable enough, and if we kept these, we were given no trouble. Had the meals been better, or even if we had been allowed to buy extra food from the Chinese, there would have been no friction, or at least very little, between us and the Japanese. The great majority of the internees, consisting of Americans, British, and in many cases their Russian wives, were accustomed to a good table. They had been enjoying large salaries in the Customs service or different companies by which they were employed; and so for these people the few thin slices of bread, with a speck of butter, was a starvation ration with which to begin the day. The dinner, too, that was served in the camp was not half a dinner to them, both as to quantity and quality, and supper was only a little better than breakfast. Men and women were losing weight, and many had heavy work to do.

When, therefore, Chinese appeared outside the wall with eggs, peanut oil to fry them in, sugar, jam, honey, fruit, and poultry, you can guess what happened. Soon a brisk trade was going on over the wall. We had been strictly forbidden to have any relations with the Chinese, and if the Chinese had relations with us the Japanese suspected us of plotting against our captors, or at least it was considered an unfriendly act. Still, the hungry internees thought the danger worth running, while the Chinese were willing to risk their lives for a few dollars’ profit. The guards at first merely seized any goods that they saw an internee buying, but gradually they became stricter. Then it became a contest between them and us, both sides organized. The buying went on and a rift took place in the hitherto good relations between the Japanese and their prisoners.

For a time, most people bought what they wanted for themselves, but soon it became necessary to leave the buying in the hands of a few. As I have already written, our hut was built against the wall, and beyond it was a road, on the other side of which lived a Chinese family with a garden and trees round their house. There was no place in the camp better suited for buying over the wall. For some time business went on ― the "Black Market" it was called ― mostly in the hospital grounds, and here the guards concentrated their attention on stopping it. People were hungry, the Japanese prohibition did not oblige in conscience, and it had become difficult to buy elsewhere ― so I began buying from the family opposite our hut. This family happened to be Christian, but Protestant, and of the same name as myself ― K'ang (my Chinese name). At first I made it a rule to buy for sick people and children only. For a month or so, I kept to this restricted circle; then, as others had to stop buying on account of the increasing vigilance of the guards, and people really in need begged me to get things for them, my business extended until I was buying for people all over the camp. Father L'Heureux did a little buying on his own, but his time was well taken up with our invalid, Father Drost. I was able to keep Father Drost well supplied with much good food he would otherwise have been without. One day, Father L'Heureux came in laughing with a few pounds of plums. The Chinese boy, who brought them to the wall for sale, perhaps through fear or because of his excitement over the danger of the deal, had asked only two dollars for them. Probably his parents had told him to ask twenty. At any rate, Father had mercy on him and counted him out twelve.

This was a very good price, seeing that the Chinese asked much more for their goods than the actual price.

As my purchases increased, several internees, including two young American Priests, helped me. Some nights we got over the wall many thousands of dollars, worth of foodstuff, clothing, and general items. We had to be very quick ― one or two received the goods over the wall, at least another carried them into the house nearby, and several were on watch for the guards at different places. I received many a pleased and knowing smile when I happened to walk through the camp in the mornings, and saw and heard the eggs I had bought sizzling in the peanut oil on the small stoves that the people had built up in their yards. The Japanese had started a canteen in the camp where a limited amount of things could be bought. It was very little ― for instance, two eggs a week ― but it served a useful purpose in that the Japanese could not tell which food was bought over the wall.

A community of Sisters once sent me down word that they were in need of sugar. I asked a Chinese to bring 200 pounds. Yes, he would bring it the following morning at seven o'clock. He brought it, and he had another 100 pounds hidden nearby. I took the 200, and the man hid in a field. Two Priests were waiting about. It was a Sunday morning when they took their soiled linen to the Sisters for the next day's wash. They wrapped some of their dirty clothes round the bags of sugar and carried all of them down the street and past the guardhouse to the Sisters. One of the Priests quickly returned with the money and said the Sisters wanted the remaining 100 pounds of sugar. I waved to the man, and within a few minutes the third bag was handed over, the money passed back, and everything around the wall became quiet again. For nearly two months we bought at that place without the guards knowing anything about it.

Now let me tell you the rest of the story about my Black Market activities. It became increasingly difficult to buy over the wall. One or more of the internees was a spy, giving information to the Japs. When they did catch me at last, they said that they knew all about it, but they wanted to catch me themselves. One spy was an old American Protestant missionary who had married a Chinese. Only after two years was he found out.

Most of our business had to be done at night. Sometimes we got across thousands of dollars (Chinese) worth of food, clothing, and other useful things. The Japanese became very vigilant. Later, a notice was posted forbidding us even to go near the wall under threat of being shot. Guards patrolled the walls with rifles. One night they passed around on the outside and came along just as we were giving our orders to a man outside. He ran, and they chased him shouting, but he was too quick for the small Japs, and as he turned down a lane, they fired a revolver after him. After that, we kept quiet for a few nights. Generally, we got the food over the wall after ten o'clock, when the lights in the camp were turned out. At midnight a man returned for the money and our orders for the next night. As the weather was warm I moved my camp bed into the yard, and the man used to climb the wall and wake me up. There was barbed wire along the top of the wall, and in order to save his clothes from being caught on the wire, the man used to climb over in a bathing suit. One night I was expecting him and got up and waited near the wall. Guards were prowling about, and I did not want him to come over the wall, for he would have been shot on sight. He appeared, standing on a small ladder about five feet long, which he had brought with him; I stood on a box. We had spoken only a few words when I heard the guards coming down the yard behind us. They had me in a corner. I quickly whispered to him, "The Japs; the Japs are coming!"

I jumped down and began to walk about the yard. The guards came up. "What are you doing here?"

I said, "I'm attending to nature."

They said crossly, "Why not go to the proper place?" (It was just across the yard).

I asked innocently: "Isn't against the wall all right?"

They began searching about the yard to see if I had got anything across. They talked among themselves and stood about. I went and got into bed with my boots on and laced up! They were no detectives! I hoped very much they would go away, but they stood about and in silence too. Then what I feared happened. Slowly and cautiously, my man's head appeared above the wall. The silence in the yard had led the man to think that the Japs had gone. One of the guards gave a roar, jumped onto the box, and fired. He missed and I heard the man running for his life around a bend in the wall. The guards pulled me out of bed. and each holding me by the wrist began to lead me to the guardhouse. My mind was working furiously. I was likely to be searched, and in my pocket was a packet containing $500, the list of goods we had just bought checked off as correct, and a note saying what we wanted the next night. How to get rid of it?

The senior guard helped me. He spoke to his companion, who released my wrist, and turned back toward our yard. I saw afterwards that he had turned my bed upside down to see if I had secreted any purchases there. Outside Kitchen number three were a number of tables where the ladies prepared vegetables. As we passed one of these, I staggered and fell to the ground with a groan near the table. I quickly pulled out the small packet, threw it under the table, and staggered to my feet. I raised my arm, the guard grasped my wrist, less firmly I thought ― perhaps out of compassion for my fall ― and we continued on to the guard house.

The officer on duty at night and the few guards who were waiting to relieve others were there. I was charged with buying over the wall. I stated my case: "I was standing near the wall. A Chinese looked over it from outside. There was no connection between the two." The officer was inclined to believe me, but the guard insisted. I said as little as I could. I wanted to delay, for I knew that help was coming. My slowness to defend myself beyond denying the truth of the charge seemed to puzzle the officer. Suddenly the door opened, and there walked in the man elected by us to represent us with the Japanese, Mr. McLaren, accompanied by the senior Priest, and an Indian whose knowledge of Japanese caused him to be frequently used as an interpreter. As soon as I was taken, some Priests had quickly gone and summoned these three. As for Fathers L'Heureux and Drost, although my arrest took place just outside their door, they knew nothing of it until the next morning. Mr. McLaren, a tall, athletic Scot, listened to the charge against me. He had great dignity of manner, and when he said to the officer in his quiet, impressive way, "That is not so bad," I knew all would be well.

They talked through the interpreter for half an hour, then the officer said that I could go, and they would call me up another time. That was just saving their face, and meant I was free. The senior priest came part of the way to our hut, and when he left me, I walked to Kitchen number three and fumbled about in the dark under the tables until I found the parcel of money and notes. The next morning, Mr. McLaren told me that when I left the guardhouse, the officer asked why I did not make more effort to explain my case. "Oh," said Mr. McLaren, "he is a silent Cistercian; they are not supposed to speak." His words were repeated through the camp and caused much amusement. The officer also said to Mr. McLaren that I certainly had a very innocent face!

The Black Market went on, but we were more careful. One evening, I alone received a box of eggs over the wall when I heard the guards coming. I put the box back against the wall of our hut, put the eggs into it, and then sat on top with an open Breviary in my hand. The two guards were in good humor. "You can't read by that light," said one.

"You will ruin your eyes," said the other.

"Oh, no," I said, "my eyes are exceptionally good." I am sure that they were slightly suspicious. They half-guessed the Breviary was only a hoax.

"Go on," they said, "let us hear you."

The light was fading fast, and I really could not read the small print. I fitted the breviary before me at a correct distance from my eyes and began to read slowly and distinctly, line after line. But it was a psalm that I knew by heart. The guards departed, and I removed the eggs to a safer place. Some people had followed the guards and listened from around the corner. These now went and told the story ― with additions or not, I do not know. At any rate, I heard it back many times, but so exaggerated and in so many different versions that I hardly recognized it as an account of what had happened.

The members of my band as well as other Fathers had many close escapes. They caught me at last. It happened like this. We placed a large order with the people opposite our hut and made every preparation. Two young men from Tientsin helped me at the wall. Others carried the things away, while a number of Priests and laymen watched for the guards. Our big order had been got across the wall and was being carried away when I heard girls' voices softly calling: "Father Scanlan, Father Scanlan!"

The warning came too late. Several girls were sitting under a tree in our yard, and one of the watchers began to talk to one of these girls. A Japanese came along, and only when he had passed the man who should have been on watch did the girls see him. I heard the calling and walked around the corner ― a ten-pound package of sugar in one hand and a packet of fourteen tins of jam in the other ― and met the Japanese face to face. He gave the usual Japanese grunt and stared at me; then he made me a sign to remain there and himself hurried around the corner. My companion was there, both hands full also. The guard, gathering up all he could carry, started off at once with him to the guardhouse. When they came around the corner, the guard looked for me, but I was gone. It was mean to desert my companion, but I knew all these things would have to be paid for. I guessed too that I would soon be joining him. At any rate, I got busy. I ran with the two parcels to another block where a friend for whom I bought things lived. His wife had tuberculosis. I rushed in and dropped the goods on the floor. "Hide these," I gasped. "The Japanese have caught me."

Without further explanation, I pulled off my black robe, threw it and the girdle behind the man's bed, and rushed out the door dressed in a white shirt and trousers that had been given to me in the camp. Clothing was hard to get. I raced back to the yard and gathering up in my arms the few parcels that remained on the ground ― the girls had taken away some ― I hurried to the room of the Dutch Lazarists. "eggs, honey, jam," I called out, and immediately was surrounded by the Fathers. They began leisurely to examine the goods, and I said, "See you later."

I gasped, and hurried back to my room. Most of the things were saved, and I sat on the bed and waited. Within a few minutes, a guard came to the door, looked at me carefully, and made me a sign to follow him. When we entered the guardhouse, I saw my companion standing silent in a corner. The officer charged me with buying over the wall, and this time there was no escape. I was caught. Mr. McLaren, the senior priest, and the interpreter came along, but all they could obtain was that I should be tried before the Commandant. We knew him to be more lenient than the junior officers. I was allowed to return to my room.

Two days later the Commandant sent for me. The same three internees were present as when we had been in the guardhouse. To the question of the Commandant, I acknowledged that I had been buying, and the Commandant gave the sentence. "Two weeks of solitary confinement," he said.

When the internees heard my sentence, the joke went around. A Cistercian sentenced to solitary confinement! "Why," they said, "he has been living that way the last twenty years!" They called it "The Perfect Punishment." I was surprised at the mildness of the Commandant. I even had a feeling that he was friendly toward me. When I entered his office, he looked carefully at me; then he lowered his eyes and did not raise them again from the paper before him.

He told me I could have my dinner, then I must go to jail. The internees called it "A jail within a jail," but it was not so bad after all. After dinner, our procession set out for the Japanese compound. There was a Japanese officer, Mr. McLaren, the senior Priest, the interpreter, and myself. Behind us came three or four laymen carrying my bedding and other things. A small stone house with two rooms stood about twenty yards from the officers' room. Here, in the smaller of the two compartments, I passed ten days. The officer locked the door, and they left me to myself.

I expected to receive reduced food rations, but Mr. McLaren and another internee, accompanied by the guard, brought me the same food as was given in the kitchens. Once a Mr. ---- brought along my food. He had been the chief of police in, the British zone in Tientsin. He was a big fat man, and his voice was agitated as he said to me, "Keep up your pecker." (Have courage.) I grinned when I noticed the agitation of his voice, because it was likely he was thinking he could have been in jail too. Although elected as one of the camp officials, and for "discipline." too, he carried on a quiet Black Market of his own in another part of the camp. One morning he received a fowl over the wall, but it got loose and ran squawking down the yard. The neighbors all helped, but it was Mr. --- who succeeded in catching it and smothering its squawks in a pair of pajamas. A few minutes later the guard appeared for roll call, and Mr. --- was solemnly standing before his door. He had wrung the bird's neck and thrown it under the bed.

The food was much better than I expected to receive. In fact, I was better fed than at any other time in the camp. The three kitchens took it in turn to send along my rations, and when it was found that the Japanese did not examine the bowls, I was sent many good things. Fried eggs and cakes, made from my own buying, sweets and fruit got from the canteen. Gradually I amassed extras; I had more than I could eat. At first, some of the internees stole along and talked with me through the window, but the Japanese found out and kept watch. Then began a series of adventures for three boys of the camp. Dennis Carter and two other boys visited me daily, and often several times a day, bringing me anything I wanted and exchanging notes for me with people in the camp. They enjoyed the danger, but in my eyes they were little heroes. Had they been caught by the Japanese, they would have been well beaten. Dennis was seen and chased a few times, but he managed to get away. It was forbidden to go into the part occupied by the Japanese. The youngest of them used to climb a tree just inside the Japanese compound and there, hiding in the thick branches, would give an agreed sign to the other two coming along as to whether or not there were Japanese about. One day a guard saw the two boys coming toward the compound and waited about. They could not pass, nor could the boy come down from the tree. Only in the evening did he get away.

The Commandant said that, with the exception of my Breviary, I was not allowed to take any books with me to jail. Mr. McLaren said that he thought it would be all right for me to put a book or two in my pocket, and this I did.

The days were very monotonous. I had brought a Mass kit and celebrated every morning, without a server and with the kong for an altar. After Mass and my Office, there was nothing to do, so, I asked for some other books, and I read or sang the day away. At night the guards passing by going on watch used to rattle the chain on my door or tap on the wall to see if I were there, and I had to call out to them. In the daytime they sometimes looked through the window. This was large, not made of glass, but the big opening was partly closed by thick wooden boards a few inches apart. At the back of my room was a small opening that might also be called a window. It was about a yard long and a foot high, closed in by bricks built in, a few inches apart. I was able to remove one of these bricks, and it was through this opening that the boys handed me in things. I hid the books when the guards came to the window or the officer came at meal times. One day, a guard came up quietly and through the window saw me reading. He glared at me and went off; he could not get in as the door was locked, and apparently only the officer had the key.

The next morning, about eleven o'clock, I heard the sound of many footsteps outside, and on looking through the window, I saw the Commandant, the officer who had the keys, Mr. McLaren, and an interpreter coming toward the room. The officer picked up the two books that I had brought with me, but fortunately those given me by the boys were beneath the blankets. On the floor at the bottom of the kong were small boxes containing fruit, boiled eggs, and sweets. The Commandant examined them carefully, but he said nothing.

Meanwhile, Mr. McLaren said to me, "He asked did you have books. I forgot you brought those two." The guard who looked through the window must have complained. Then through the interpreter the Commandant explained that it was forbidden for me to read and that he would take away the books. He would return them to me later. Then he said, "There is another matter. You are singing."

"Of course," I said. "Isn't that all right?" The interpreter, a half-Japanese, but interned because he had British citizenship, explained that in Japan a prisoner must keep absolute silence, and the officers in the building nearby considered I was making light of them by singing. Already word had passed through the camp that I was so pleased to be again a solitary that I passed the time singing my prayers. I confess it was American songs I was trying to sing.

The Commandant interrupted the interpreter to say, "If he stops singing, I'll let him out a little before the time."

I was pleased to hear I had a chance to shorten my time, but still more pleased with the friendly attitude of the Commandant, so I protested that I had no intention of mocking the officers by singing and that I would certainly not sing any more. They left the room, and this time it was with a feeling of relief that I heard the key turning in the lock. It was an unexpected visit, and I was left wondering why the Commandant was so easy with me. He could have objected to all the food in my room, but he only asked me not to sing, with a promise of a reward if I obeyed. He had showed no displeasure at all, but I heard later that after they left my room, he told Mr. McLaren that he was a liar for saying I had brought no books with me.

Three days later, at about the same time, I again heard voices, and the same party approached, but without the commandant. All were smiling, even the officer. I had been in jail ten days., and because I had stopped singing, they had come to free me four days before my sentence expired. The next day the Commandant sent down the books he had taken from me. After I left the camp, I heard that he was a Catholic. He never attended Mass in the camp, but there was sufficient reason for him not to do so under the circumstances in which he found himself. Now I understand why he had been so lenient with me.

The internees of Kitchen number one were seated at dinner when I walked in. They gave me a great ovation. The shouting and singing were heard in the other two kitchens, though they were some distance away. I spent the next afternoon going around the camp with Dennis Carter as my guide to pay a visit to all who had sent me sweets and prepared special food for me while I was in jail. On the following Saturday all the interned Australians and New Zealanders invited me to a tea party, where we had quite a feast, with songs and speeches. The women managed to make some cakes for the occasion, mostly from material that I had bought over the wall, and the priest in charge of the making of the bread baked them. They were very good. I sang a song about Australia, which I had composed in jail. The Australians praised it, but a Canadian Priest to whom I sang it one evening said the words were all right but the music was terrible.

Then I thanked the three boys who had been the messengers. I invited them to my room, where I had prepared a really good spread, some friends in the camp having made up some special dishes for us. I myself prepared three pounds of plums, which I had bought the evening before I was caught. There was too much food for the occasion, but the boys did their best to finish it. I never saw boys so gorge themselves in my life. When they could eat no more, they lay about the room puffing. They simply could not swallow any more. After a rest they went for a walk around the camp and returned in the evening and again helped themselves. Dennis had one sister, older than himself. The family were Anglicans, but Kathleen had become a Catholic and Dennis followed her later. The day after the feast I asked his sister how her brother was. She answered rather crossly, "The little animal! When he got into bed, we had to tuck him in, or he would have rolled out onto the floor."

During the weeks that remained of camp life in Weihsien, I was invited to tea all over the camp. From that time, I did little Black Market activity ― only when we had some special need. The internees themselves asked me not to do it. They were afraid that if I were caught again, I might be sent down to Tsingtao, the port on the tip of the Shantung Peninsula. Here the Japanese had several foreigners imprisoned, and they were given a very rough time. I was not allowed to forget my Black Market activities. Even years later, I was reminded of it again and again. It occasioned much fun, and we often laughed over the escapades we had with the Japanese when trying to get the food over the wall. So that is the end of the story of the Black Market.

Washing our clothes was a difficulty. Things were so inconvenient, and even soap was wanting to many of us. I bought much soap and many washing boards over the wall. Some American Sisters offered to wash the clothes of the three Trappists from Yang Kia Ping, but on condition that I carried the water. I began to bring the water, but they complained to Father L'Heureux that the water was not half hot enough, also that I was sometimes late. Father L'Heureux said nothing to me about the complaints, but he offered to help me, and I was very glad to have his help, The Sisters' washing hour was my busy hour over the wall. It soon happened that my helper was doing all the work himself. I heard afterward that he used to see about the fires (though this was another man's job), so as to have the water nearly boiling.

When the Sisters arrived, the tubs were full and soiled linen was spread over the top to keep the water hot. When the Sisters were ready to start, Father lifted off the coverings and departed. I can imagine the scene as Father lifted off the clothes and the steam went up, delighting the hearts of the hard-worked Sisters. Father would extend his hands, give the Sisters a little bow and a smile, and then take his departure. It would be the same display of politeness as that which won the favor of the Japanese Governor at Che Lu Hsien and of Colonel Watanabe. The Sisters once brought him down a cake that they had managed to make. He gave most of it to Father Drost; I do not know what became of the remainder. I know I received none, and I thought it prudent not to ask for any.

The internees had to do all the work necessary to keep the camp going. Chinese coolies were employed only on the carts ― bringing in the food supplies and carrying away the refuse from the dump heaps. An "Internees Labor Bureau" was set up to regulate the work. There were bakers and blacksmiths, gardeners and cooks. Some pumped the water; some had to keep the closets clean, and others the streets; some unloaded the coal carts and carried the coal to the kitchens. Lighter work was preparing the vegetables and cleaning out the refectories. The Priests soon became recognized as the best workers in the camp, and it was they who did the heaviest work. They were skilful too; they were accustomed to turning their hands to almost anything on the missions. On that account they had a great advantage over the seculars, most of whom were used to coolies doing the work for them. The Sisters, too, soon gained the same good name as the Priests. By common consent, an American Sister was put in charge of all the kitchen arrangements, regulating supplies for the meals, and so forth. Both Priests and Sisters were very popular. On the other hand, the Protestant missionaries, especially the men, were married and had their families with them. Consequently, unlike the Priests and Sisters, they were kept busy providing for their own.

Because of the work and of the uncertainty of being able to buy clothing, we soon abandoned all pretence of keeping ourselves "dressed." Men often worked stripped to the waist, and the Priests during work time were not much better dressed. In summer women discarded all they could, not only for comfort's sake, but in order to make their clothes last as long as possible. As time went on, more and more people had to go barefoot.

After the light breakfast followed by the morning work the dinner hour was punctually observed. At the three kitchens, the queues of hungry waiting people stretched down the streets, every one falling in place as he came ― be he Bishop or Reverend Mother, or the head of the British coal mining company, or the Lord Mayor of Tientsin ― each took his place in the line the same as the poorest man or the children. Each grasped the all important bowl, his knife and fork, and his spoon. Sometimes there was a delay. The Japanese soldier in charge of the stores, to whom we gave the name of "Gold Tooth," was not very strong in English. Some claimed, too, that he was mentally deficient. At any rate, if he failed to understand what was asked for by the representatives of the three kitchens, he would fly into a fit of anger, drive all from his presence, lock up the stores, and depart. Some discreet person would then be sent to smooth his ruffled humor, and it was a few times only that it was necessary to have recourse to the Commandant. On such days dinner would be delayed. The longest I remember was three hours; some of the people returned to their rooms; others kept their places in the queue, but seated under the trees on the pavement.

Dinner consisted of meat, vegetables, and bread. Everything was strictly rationed. Sometimes the women managed to prepare a "sweet" of a kind. Only a little meat was given; sometimes there was none at all, for it was difficult for the Japanese to obtain a regular supply. As we filed past with our plate or bowl, one, generally a lady, marked our meal tickets; another gave the piece of meat; another the potatoes or potato; another the spoonful of cabbage or some other vegetable. We passed on, and another lady handed over the two or three thin slices of bread. Then to your place to look cheerful, whether you felt it or not, which you usually didn't. Occasionally there was a little left over when all were finished. Then a spokesman would shout, "Seconds for vegetables ... " and there would be a rush till the second message came, "No more seconds," and those who were disappointed would saunter back to their places.

The Commandant allowed us full use of the Sports Field, and there we could run and shout as much as we liked. The guards themselves played the American game of softball, and on a few occasions they even challenged a junior camp team to a match. They did not do well; it was not their national game. However, for us the sports were a great success; they had a very good effect on the spirits of the internees. The game of softball was the greatest attraction both for players and spectators. Many teams were organized. There were two senior teams ― the American Fathers and the Tientsin laymen. There were four second-grade teams. One was picked from the laymen of the camp, men who were "old sports" but now getting on in years. Of the other three, two were formed from Dutch and Belgian Fathers, and the remaining one was a team I raised from among those who helped me one way or other with the Black Market. We were called the "Black Marias." We dared not take the name of the Black Market team, because the Japanese read the notices. I was the captain of this team, and I made up by my enthusiasm what I lacked in skill, speed, and agility. Some games were lost, and some we won. When our pitcher (bowler) was unable to come, I took his place. My experience on the cricket field stood me in good stead.

The girls also formed several teams and played among themselves. 'Their winning team even had the astonishing hardihood to challenge my team ― the "Black Marias." We did not deign even to answer them.

Some really great games were witnessed between the senior teams. One of the Fathers, Father Wendy, the captain of the American team, who was as fine a priest as he was an accomplished sportsman, was said to be one of the best softball players in America. Two or three other Fathers were good enough to have played in the American national softball teams. The American Fathers usually won, but it was generally only after a great tussle. These Fathers were the favorites, and as for the poor neglected Protestant parsons, I do not know if one of them played in any team.

Some of the senior games were played immediately after supper. The days were long, and the cool of the evening was suited to the sport. Almost all the camps used to repair to the field and scenes of the greatest enthusiasm took place. It was a relief to the people to have an opportunity to relieve their pent-up feelings, and the excitement of the game made them forget for a time the difficulties of their concentration. Men, women, and children shouted, blew whistles, and rattled tin cans loaded with stones; supporters leaped into the air when their side scored a run; there were cheers and counter cheers; young men and boys rushed from one side of the field to the other to get a better view.

I asked Father L'Heureux to play on my team. He declined, saying he had never played softball in Canada. Tennis was the only sport he went in for, or rather, I should say, it was the only exercise he took. The two Jesuit Fathers, who also played, used to come for him. They left their tennis rackets and balls in our room, and Father L'Heureux used to take them when he was free and have a game. People said that he was the best player in the camp. This surprised me, for among the young people, there were many good players. He and the Jesuit Fathers ceased to play when the hot weather set in, probably because the girls who also used the courts were rather scantily clad.

I had good proof of how athletic he still was. One evening, when buying over the wall, I happened to drop a one hundred dollar note into a basket, which along with some wrappings, I threw over the wall. I thought the money was gone. The wall was seven feet high, and besides, it would have been extremely dangerous to scale the wall. Had one of us been seen outside by the guards, he would have been severely punished, perhaps even shot on sight. When I entered our hut, I told Father L'Heureux that I had lost a one hundred dollar note. He asked me to show him where I had thrown the basket. He looked about, examined the wall, and without a word and without help, he grasped the ledge of the wall, drew himself up, and swung over. I ran back to see if there was a guard coming. When I returned, he was already back in the yard, and with a little laugh and much shortness of breath, he handed me the one hundred dollar note.

Now I wish to dwell at more length on the part the Priests played in the camp. I already wrote of it in the account of our week at Hwailai, when telling the story of how Father L'Heureux caught me doing elocutionary gymnastics in the company of the Protestant missionary ladies.

Although the 1,700 internees differed in religion, in rank and state of life, in education and fortune, we were brothers in distress, and all realized the necessity of charity and mutual help ― of trying to make oneself all things to all men. The Priests did this, and soon they became the moral leaders of the camp. The Sisters, too, by the willingness with which they put their experience and all-round knowledge of the management of affairs, and their hard work, too, at the service of all, were universally admired and respected. Not only religious services, but also work and play benefited by the energy and organizing genius of the Priests. I have already written of the popularity of the American Fathers' softball team, and of the Sunday evening concert given by the Dutch and Belgian Fathers. The American Priests also had a band, and it was a picture to see some of the Sisters as well as laymen seated on the stage and playing with them. I remember seeing a priest playing with the Salvation Army band on the Sports Field.

This active cooperation on the part of Priests and Sisters not only helped very much to keep up the spirits of the camp, but it also kept up the standard of morals. Many in the camp were not interested in morals, and during the period of their long, forced inactivity, there was grave danger of morals becoming openly flouted. To give a single example. An actress from Tientsin one night at a concert made an exhibition of her bare legs. Next day we quietly made it known to some of our lay friends that if the concerts in the hall did not keep up to a certain standard, the Priests would not be able to attend. As we expected, the words were passed on and it was enough. There was nothing objectionable after that.

Generally, Father L'Heureux did not join with the other Priests in organizing the different activities of the camp, nor did he take part in them. For the first two months his time was taken up looking after Father Drost, and in any case, he and the other two Cistercians from Liesse thought that we ought to live as quietly as possible. However, on one occasion he was appealed to, and now I will tell you how he responded.

About twice a week, the young people held dances; American negroes supplied the music. Sometimes these dances were not very nice. Some wished to counteract this and proposed the holding of folk dances. It was the women and girls who did the organizing, but when they met on the first evening, it was found that few of them knew the dances well enough, and they did not even make a start. A notice was put up, asking anyone who knew the dances to go along and act as teachers. I had been taking no interest at all in the matter, when, one evening, a Priest passing by called out to me, "Go up to the tennis court and see your brother dancing." I went at once and this is what I saw. A number of girls were dancing with an equal number of Priests, and Father L'Heureux was in the midst of them ― in fact, he seemed to be directing the operations. I looked at him in astonishment, for I did not know there was a step in him. No one had volunteered to help the girls to get a start with the folk dances, and some Dutch and Belgian Fathers along with Father L'Heureux had stepped into the ring from among the crowd of spectators.

The Priests could do it very well, and when I arrived, the dance was in full swing to the music of an accordion-piano played by an American Father. Naturally, my attention was mostly given to Father L'Heureux. He danced gracefully; his body as well as his feet kept time with the music. He put out one foot, then the other; he advanced and swung his partner's hand over his head; they circled about, and he danced backward. Occasionally, he had to wait for his partner and put her right. He did it all with so much smiling solemnity that he could have been giving a lesson in church ceremonies.

The object of the dance was a great success. Not only were the folk dances started, but the priests also made it known what kind of dances they liked, and incidentally, what kind of dances they did not like. When Father came into our room, I said to him, "I never thought you could do it."

He said simply: "I learned that with Denise." It was the second and last time that he spoke that name. I remembered it was the same person he told had me about when we sat close together on the kong at Che Lu Hsien ― the girl who had been the friend of his youth, and for whom he had evidently so much esteem and regard.

Another result of the good relations between the Priests and the laity was that many Protestants attended the grand High Mass that was celebrated every Sunday in the "church." So many attended that some of the priests stayed away in order to leave room for them. Several Protestants began to take instructions, and within a few months there were several Baptisms; "drifted" Catholics were reconciled to the Church; marriages were put right. The cheerful, willing spirit of the Sisters and Priests drew the attention of all. Many said, "I never thought Priests and Sisters were like that."

We were not without our difficulties. Among other things, the supply of Mass wine and candles was very uncertain. During Mass one candle was lighted, and that from the Sanctus until after the Priest's Communion when it was again extinguished. The amount of wine that would ordinarily be used for one Mass had to last a fortnight or more. For Confessions, we chose any quiet spot; the several Bishops among us decided that any place could be legitimately used. People went to Confession walking up and down the road, sitting on a fence, or lolling on the ground while watching the games on the Sports Field.

Our concentration camp was probably the best in the Far East; the Black Market was the only sore spot between the Japanese and the internees. It was a pity the Commandant refused to make arrangements for the provisioning of the camp, and to allow the internees to buy from the Chinese. The reason given for our not being allowed to buy over the wall was that we would obtain firearms. This was true, but the Chinese could have been permitted to enter at a certain time daily and their goods examined at the gate, as other things were. Once the guards searched a young Chinese at the gate, and they found his padded trousers from the knees to his boots packed with eggs. He was subjected to the water treatment. This was a favorite torture of the Japanese. A soldier held the victim's nose and another poured gallons of water down his throat. He could not refuse to swallow, because he had to open his mouth to breath. When his belly was swollen like a barrel, the soldiers often kicked it, stepped on it, and jumped on it. Occasionally, a man died under this treatment, but generally he recovered and was none the worse for his big drink. Sometimes, rice was first poured into the man. This made the ordeal much worse, for the water caused the rice to swell in the poor fellow's stomach.

As I have already written, the provisions given out for supper were meager and uncertain. Often we came away hungry. One evening there was almost nothing to eat, and all were discontented. After leaving the kitchen, many gathered outside the doors, dispirited and discouraged. They complained among themselves that the Japanese made them work but would not feed them. That week a group of Dutch Priests were the cooks. They too were hungry, and they had the added disappointment of having to prepare so little for us. Suddenly from the kitchen came the sound of song. It was in a language we did not understand. Then the word went round, "The Dutch Fathers!" And how they did sing. Song followed after song, and with a swing and vigor that delighted us all. They were not hymns, but popular Dutch songs. Crowds gathered in front of the buildings, and it was remarkable how it cheered them up. The songs had a message for them, "Don't be downhearted, we won't be downhearted!" People began to smile, and they dispersed, feeling better.

A lecture was arranged for every Tuesday night in the big room called Number 25. Every subject got its turn, from religion to travel in the jungle. I was asked to speak on the Trappist life. Whether it was due to my notoriety as a Black Marketeer, or to the interest felt in our unusual kind of life, the room was crowded and the doors were closed before I began. A few weeks later, I was asked to speak on the same subject, and again the doors had to be closed before the time to begin. Our life of silence was a riddle to the people; there was an audible gasp among the listeners when I said that, during the first ten years of my Cistercian life, that is, until I was appointed Master of Novices, I had observed almost perpetual silence, speaking only to the Superior on necessary matters.

Father L'Heureux rarely went to these entertainments. Moreover, being a French-Canadian, his English was not perfect. Of the other three, Father Drost was always under doctor's orders, and the two Priests from Our Lady of Joy were Belgians. Only one of them was studying English.

Among the notices which I was asked to read out on the evening of our arrival in the camp, there was one which aroused an especial interest and pleased us. It was that we would be allowed to write a letter once a month ― subject, of course to Japanese censorship. In practice, this good intention of the Commandant fell through. Naturally, he wished to have the letters read over before he sent them out, but he could not find Japanese who could read them. There was quite a variety of languages: English mostly, but also French, Dutch, Greek, Russian, Indian, Chinese. At first, some letters were dispatched, but as time wore on, our post became more and more uncertain. Some letters were passed to Chinese outside the wall with a good tip, asking that the letter be posted in small villages some miles away, so that there could be less danger of the Japanese detecting our secret post. It was dangerous but successful, and it happened more than once that Chinese servants came from afar, for instance, Peiping or Tientsin, with a letter in reply or with money or something else that had been asked for. I received some answers in this way over the wall and handed them to the addressees.

Our incoming mail was more regular. These letters were also opened by the Japanese. The writers knew that they could write about their homes, and so forth, and must not report war news. But it was war news that we wanted. Gradually the internees and their friends outside devised a language of their own by which they gave and received information about our camp affairs and about the war. I saw one cleverly written letter by which we knew that British planes had begun to bomb Germany. The planes were pigeons that flew into a troublesome neighbor's garden. Hopes of peace were written of as doves. Later, either the writers became too bold, or spies in the camp gave information, for the Japanese found out what was going on. Some of the writers were beaten up, and the safest course was not to write at all. I did not see Red Cross letters received in the camp. We wrote some, but I do not know if they were ever sent out. I was back in Peiping several months when I received my first wartime letter. It was from my brother Mick. Always audacious, he addressed it to the Red Cross in Japan, and it was readdressed to me in China. I was immensely pleased with it.

This account of our life in Weihsien would not be complete without a few words about rumors in the camp. These played quite an important part in our daily drab existence. Ask an ex-Weihsien internee if there were any rumors passed about in the camp, and he will surely smile. There were many ways of hearing things or half hearing them: perhaps the Japanese were overheard speaking among themselves; perhaps someone saw a newspaper that was wrapped around the supplies that the coolies brought in the carts to the canteen; perhaps it was shouted to us from beyond the wall; The possibilities were endless.

Of course at that time the future was shrouded in doubt. Some held that Japan would win the war, especially when we heard that the German armies were pushing farther and farther into Russia.

What did the rumors tell of? The greatest variety of things; there was an army of Chinese irregulars not far away, and they intended to seize the camp and set us free; the Weihsien internees were to be taken to Japan and interned there; England was about to sue for peace; a revolution had broken out in Russia; America and England were about to set up a new "front" in South China by means of troops flown over the Himalaya Mountains (!); a Japanese army had landed in Australia, and so forth.

These rumors passed through the camp like wildfire. They proved to be false, time and time again. Still, we were eager to hear the next one. We would ask what was the latest news ― that meant, the latest rumor. We did not know but that it might be true. If the rumor told of something to our advantage ― well, well, you never know, we said to one another, it could be; and we lived on in this way, from day to day, always anxious to hear something that might show us that the end was coming, that our internment would be soon over. Anything that aroused our hopes we grasped and welcomed ― though we knew in our hearts that it was an idle grasping at a shadow. Our forced inactivity and complete ignorance of what the future had in store weighed heavily on all.

There was one rumor that proved to be true. The Priests, and still more, the Sisters, had reacted nobly to the difficulties of their internment. Led by the example of the seven Bishops, they had tried to make themselves all things to all men, and the results of their efforts had decidedly raised the standard of the camp and enabled the people to face more courageously the long, dull days. Still, the camp environment was trying to them. It was not their life, and none of the internees were more out of their surroundings than they were.