APPENDIX

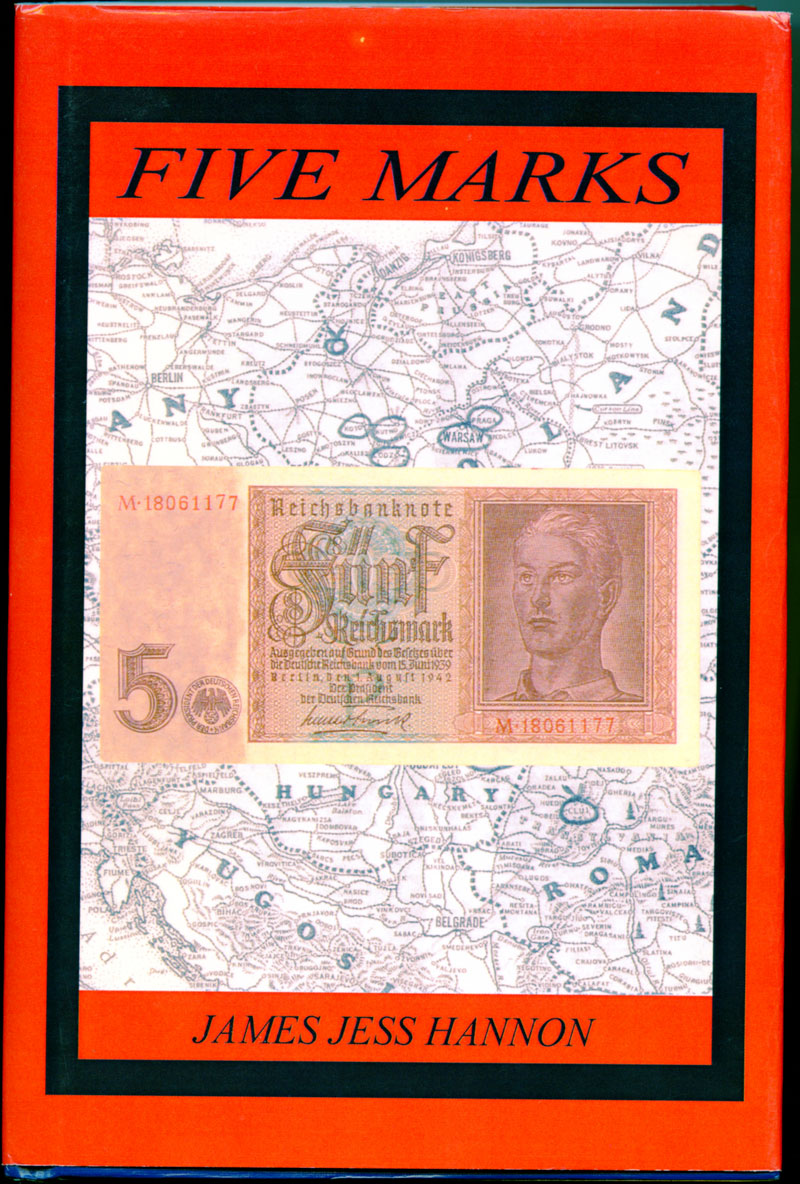

A copy of a printed book, `Majdanku', translation Maidonek, was given to me by Basiz Zygmunt, a man who gave me a hot meal and shelter for the night in the town of Lublin.

Basiz pointed across the valley and said, "Maidonek — death camp — more than a million people went up that stack and floated down everywhere — black snowflakes contaminated the air, the streets, public places, school yards, church yards, markets, our homes, our clothes, our minds — one day, translate this book into English."

That `one day' came 57 years later in May of 2002. The pictures are also from this book, `Oboz W Majdanku' described in my Chronicle, FIVE MARKS.

I was there, February 1945, overwhelmed by the ghastly slaughter house just as the German's left it in the month of August 1944 described in detail in FIVE MARKS

James Jess Hannon

BORYS GORBATOW

THE CONCENTRATION CAMP

AT MAJDANEK

(Obóz w Majdaku)

FOREIGN LANGUAGE PUBLISHING HOUSE

MOSCOW 1944 |

DECLARATION

BY GERMAN GENERAL MOSER

TO THE RED ARMY COMMAND

Lieutenant General Moser, Former commandant of the 372nd Field Command in Lublin

DECLARATION

I, Hilmar Moser, was born in the year 1880 in the town of Langenorla (Rosa district). I have served in the Germany army since 1902. I was promoted to the rank of major general in 1935, and that of lieutenant general in 1942. I have been recipient of all German decorations and awards for service in combat.

For 42 years I have been a conscientious soldier, I have taken part in two world wars, and have been seriously wounded.

I have no reason to gloss over or cover up the monstrous crimes of Hitler, I consider it my duty to tell the whole truth about the "extermination camp" built by the Hitlerites near Lublin, along the Chelm highway.

At the end of November 1942 I arrived in Lublin as commandant of the 372nd Field Command.

My predecessor, General von Altrock, along with his field command, was transferred about three weeks later to the East. In briefing me about his duties, he informed me that there was a concentration camp at Lublin run by the SD [Translation's note: SD—Sicherheitsdienst — Security Police]. He started that according to military regulations, the commandant of a field command, being a representative of the Armed Forces, was strictly prohibited from visiting the camp or inquiring about what went on there.

Shortly thereafter, General of the Infantry Heinicke, commandant of the Military District of the General Government [Translator's note: Official name given to German-occupied Poland] arrived in Lublin; the field command was directly under his jurisdiction.

He repeated the regulations that Gen. Altrock had told me about, and reiterated the strict prohibition against concerning myself with what was happening in the concentration camp.

Among other things, he told me. "What's going on there is like molten iron you don't want to touch it!"

In the first phase of my tenure I made every effort to familiarize myself with the area under my jurisdiction. Later I attempted to gather factual information about the concentration camp. I learned the following:

The camp extended several kilometers along the Chelm highway and several kilometers into the adjacent terrain. I estimate it covered about 30 square kilometers. Some direct railways spurs led from the main RR station to the camp. On the outside it was surrounded by an ordinary barbed wire fence, with a guard house a short distance inside.

I don' t know when the camp was built;

I don't know that while I was in Lublin it expanded considerably.

On one occasion, while inspecting potential sites for construction of the "Lublin Defense Zone" fortifications, positions that ran along the east wall of the concentration camp (outside the enclosure), I was also about 30 meters inside the camp enclosure with some other officers, who were in charge of the construction project.

I had no intention of visiting the camp itself, which, as I mentioned before, was strictly off-limits for the reasons stated above.

Nonetheless I found out a great deal about what went on there.

Everybody in Lublin called it the "concentration camp" or the "Jewish camp," since in the beginning its inmates were mostly Jews; later there were representatives of a wide range of nationalities, so-called political criminals, including Germans.

During the winter of 1943-44 a large number of prisoners were put to death there, including, I was appalled to learn, many women and children.

The number of deaths reached the hundreds of thousands.

The victims were either shot or gassed to death.

More than once I was also told that the condemned were forced to do extremely arduous work, depleating their strength, and that as they worked they were severely beaten.

I was also appalled to learn that the victims were tormented and physically tortured before being put to death.

In the spring of that year a large number of bodies were exhumed and burned in specially built ovens, clearly to erase any trace of crimes committed on Hitler's orders.

The huge ovens were built of bricks and iron; they constituted a large-capacity crematorium. The stench of death drifted into the town from the east, so that even the poorly informed citizenry knew what was happening in that horrible place.

I obtained information about the dreadful camp through conversations with the following persons; General von Altrock—my predecessor, commandant of the field command; General Renner, former commander of the 174th Reserve Division in Lublin; Major Gleisner, commander of the 991st Landwehr Rifle Battalion; Doctor Klaus and Osor, chiefs of the Regional Provisions and Farm Resources Group, and Major Hartmann, who for five years was my adjutant and confidential aide.

I personally asked Major Hartmann to find out what was happening in the camp, and he provided me with detailed information.

The most compelling validation of the information I received was the foul odor that I myself was so often witness to.

I have no words to express my revulsion at these incredible atrocities and I believe that any decent German should renounce a government capable of ordering such organized mass murder.

Evidence that the operations of the extermination camp were directed by. Hitler's authorities can be drawn from the fact that Himmler himself visited the camp when he came to Lublin in the summer of 1943.

I consider it my duty as a general and a soldier with 42 years in

the army, a combat veteran of two world wars, a survivor of serious injuries, and the last commandant of the Lublin district field command—to cooperate in bringing to full light all the atrocities that were perpetrated in the concentration camp. I call upon all members of the military forces under me in Lublin to gather together information on all the crimes they know about that took place in the Lublin extermination camp.

Lt. Gen. [Hilmar] Moser

August 29, 1944

THE POLISH-SOVIET COMMISSION

ON MAJDANEK

(Polpress communiqué) |

Near Lublin in the Majdanek extermination camp the German occupiers perpetrated the mass murder of Soviet prisoners and Poles, French, Czechs, Jews, Belgians, Hungarians, Serbs, Greeks and immates of other European nationalities.

In view of the fact that the Germans carried out mass murders of Soviet prisoners in that camp, the Polish Committee for National Liberation approached the Soviet government with a proposal to create an Extraordinary Polish-Soviet Investigative Commission to investigate the German crimes in Lublin and to appoint its representatives to the Commission: Prof. M. Graschenko, Prof. Prozorovski and Prof. D. Kudriavtsev.

The Extraordinary Polish-Soviet Commission was headed by Mr. Witos, vice chairman of the Polish Committee for National Liberation. The members of the Comission—Rev. Dr. Druszyñski, Prof. Bialkowski, prosecuting Magistrate Balcerzak of the Appeals Court, Prof. Of Forensic Medicine Szyling-Synagalewiez, and a representative of the Polish Committee for National Liberation, Dr. Sommerstein (Poland), Prof. Graschenko, Prof Prozorovski and Prof. Kudriavtsev (USSR) — proceeded to investigate the German fascist crimes in Lublin with the aim of identifying and disclosing the names of the organizers and direct perpetrators of said crimes.

Lublin, August 17, 1944.

Reczpospolita

THE CONCENTRATION CAMP AT MAJDANEK |

When the wind blew from the direction of Majdanek, the citizens of Lublin closed their windows. The wind brought a foul odor to the town. You couldn't breathe. You couldn't eat. You couldn't live.

The wind blew from Majdanek and filled the people with fear. Black, foul smoke poured steadily from the smokestack of the camp's crematorium. The wind carried the smoke to the town. The heavy stench of death hung over the people of Lublin. There was no way to escape it.

The Poles called the Majdanek crematorium "The devil's ovens" and the camp was known as the "death factory."

The Germans showed no restraint in occupied Poland. They wanted the Poles to smell death every day, because fear helps control rebellious spirits. All of Lublin knew about the "death factory." All of Lublin knew that in the Krebecki forest Russian prisoners of war and Poles from Lublin Castle were being shot. Everyone saw the trainloads of doomed victims being brought here, to the camp, from very country in Europe.

Everyone knew the fate that awaited them the gas chamber and

the oven.

The wind from Majdanek tapped on the windowpanes, "Poles, think about the devil's ovens, think about death! Remember that there is no life for you—there is only insert existence, impermanent and desolate. Remember you are merely raw material for the devil's ovens. Remember, and tremble!"

The foul odor hung over Lublin. The foul odor hung over Poland. The foul odor hung over all of a Europe tortured by Hitler's henchmen.

The foul odor was the weapon with which the Germans planned to suffocate humanity and rule the world.

"Dachau No. 2" was what the Germans first called the SS forces' concentration camp at Lublin. Both in terms of magnitude and

operations, the "death factory" at Majdanek far outstripped the horrors of Dachau.

We found ex-prisoners of Dachau, Buchenwald and Auschwitz there.

"Things are much worse here!," they said, "Much worse...!"

The death factory covered twenty-five square kilometers with all its facilities: prison yards or compounds, spaces between them, gas chambers, crematoriums, trenches where shootings took place, gallows for hangings, and a brothel for the German camp guards.

The camp is located two kilometers from Lublin, close to the Lublin-Chelm highway. In the distance you can see its guard towers. The barracks are all identical lines up with mathematical precision. Each is clearly marked with a distinctive "address" placard. All together they form a yard (called a "field"). There are six "fields" in the camp, and each is its own world, separated from the neighboring world by barbed wire fencing. In the center of each field was a prominently positioned gallows, used for public executions. All the roads in the camp are paved; the grassy areas are well manicured. In front of the German administration buildings there are flowerbeds and wicker lawn chairs for relaxation in the bosom of nature.

In the camp there are workshops, storerooms, a water plant and an electric lighting plant. One facility was used to store canisters of "Zyklon" for the gas chambers. There were yellow labels on the canisters: "Special—for Eastern Areas" and "To be opened by trained personnel only." There is a shop where they made clothes hangers. The hangers bore the SS insignia. They were distributed to the prisoners before entering the gas chamber. The victims themselves had to put their clothes on the hangers.

Cabbages grew profusely in the camp's yards. Plump and inviting. But they were inedible. They were nourished by blood and ashes. The Germans strewed the ashes of the crematorium victims over the yards. Their gardens were fertilized by human ashes.

The whole camp gives the impression of an immense factory or a large industrialized farm. But for the foul odor, even the crematorium ovens have the appearance of small electrical smelting furnaces. The German company that produced the ovens designed them with a look

to the future by mounting serpentine coils onto the pipe to proved a constant supply of free hot water.

Thus the factory, which seems inconceivable, but which existed in reality, was a death factory. A death mill. Everything here, from the quarantine facilities to the crematorium, was designed for the annihilation of human beings designed with rule and compass, blueprinted and discussed with German physicians and engineers as if the projected facility were a slaughterhouse.

The Germans did not succeed in destroying the camp when they retreated. They were only able to burn the crematorium building, but the ovens themselves remained intact. A table on which the murderers stripped and robbed their victims also survived. Half-carbonized skeletons were also preserved in the "corpse dump." To this day a nauseating odor of burnt human flesh permeates the crematorium.

The entire camp has been preserved. The gas chambers. The barracks. The storerooms. The gallows. Barbed were entanglements with alarm systems, dog paths. Even the dogs, Germans shepherds, were left behind. They stare warily from their kennels, perhaps bored by the inactivity. They now have no one to attack and mutilate.

Some prisoners managed to evade the hands of the murderers. There are witnesses, many witnesses. And some of the murderers were caught.

We spoke to them all.

"I lived through it!" says a rescued prisoner, who himself does not understand how he survived.

"I saw it!" says a witness who himself does not understand why what he saw didn't drive him insane.

"We did it," say the murderers blankly.

Every word of what we're about to relate can be confirmed by documents and testimony of witnesses and of the Germans themselves.

Finally we can rip the veil off Majdanek and reveal to the whole world the story of Lublin's "extermination camp."

Extermination camp. Vernichtungslager.

International death camp.

Over its gates might well have been emblazoned "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here. Ye shall never return."

Trainloads of doomed prisoners arrived here from all parts of occupied Europe. From occupied areas of Russia and Poland, from France, Belgium and Holland, from Greece, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, from Austria and Italy, from other German concentration camps, from the Warsaw and Lublin ghettos. To be annihilated.

Here, in the remote eastern corner of Poland, it was possible to do the things that the Germans might have found difficult to do in the West. Here they finally put to death all who had managed to endure and survive the hard-labor regimes of Dachau and Flossenburg. Anyone who was still alive, who breathed and could crawl, but could no longer work. Anyone who opposed the invaders. Anyone sentenced to death by the Germans. People of many different nationalities and ages—men, women and children. Poles, Russians, Jews, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Italians, French, Albanians, Croatians, Serbs, Czechs, Norwegians, Germans, Greeks, Dutch, Belgians, Greek women with shaved heads, with numbers tattooed on their arms. Blind martyrs of the underground "Dora" factory where the "V-1" missiles were made. Political prisoners from German camps with red triangles on their backs, ex-convicts with green, "saboteurs" with black, sectarians with purple, Jews with yellow. Children—from babes in arms to adolescents. Those under 8 were put together with their parents. Eight-year-olds and even "delinquents" were assigned to common barracks. Children reached adulthood very early in the German death camps.

How many hundreds of thousands were murdered in that international death camp? It is hard to say. The ashes of the cremated victims were scattered over the fields and the neighboring countryside by the wind.

But a terrible reminder remained.

Behind the crematorium there is an enormous storehouse. Heaped to overflowing with shoes squashed, crumpled, compacted into

piles hundreds of thousands of shoes, boots and slippers.

The victims' footwear.

Tiny baby shoes with red and green tassels. High-fashion women's shoes. Ordinary kneeboots, warm old women's boots.

Footwear of people of different ages, wealth, social status, nationality. Stylish Parisian women's shoes beside the boots of a Ukrainian peasant. Death leveled them all. The owners of this footwear were similarly packed into a common grave to die.

It is appalling to look at those piles of shoes. They were all once worn by human beings. They walked on the earth. They trod the grass. They knew the boundless sky was above their heads. They breathed, worked, loved, dreamed... They were born for happiness as birds are born to fly.

Why did they become victims of this unspeakable tragedy? Why did death cut them down? Suddenly they're gone... The wind had dispersed their ashes... Only dead shoes, crumpled and torn, cry out, as only dead objects can...

What motivated the Germans to keep these dreadful souvenirs? Why did they collect and preserve them here?

We found the answer in a remote corner of a barrack. Collected there were stacks of shoe parts: soles, heels, uppers. All neatly sorted with German precision. All neatly separated into lots.

They were all bound for Germany.

Like ashes over the countryside, like the heat from the crematoriums to the coils. Blood on shoe soles doesn't smell!

Only the Germans are capable of that!

The assistant administrator of the camp was an SS man named Tumann. Witnesses say that he was never without his huge German shepherd.

Germans love dogs.

They love to play with them, feed them, spar with them. They quickly find a common language with dogs. Crematorium chief Munfeld had a well-behaved little dog. The chief of the Russian POW compound amused himself playing around with a favorite mastiff.

SS man Tumann never missed a single shooting, not a single execution. He especially liked to take part in them himself. If a car headed to witness an execution was full, he would jump onto the footboard just to get there.

Crematorium chief Munfeld even lived in the crematorium. The foul odor that was stifling the entire city of Lublin didn't bother him a bit. He maintained that the smell of burnt bodies was pleasant.

Munfeld loved to joke with the prisoners.

Encountering them in the camp, he would inquire in a kindly voice, "Well, how are you, my friend? See you soon at my little oven?" Than, slapping the terrified victim on the shoulder, he would say, "Oh no, don't worry; I'll have the oven nice and warm for you."

The he would walk away, with his dog at his side.

Witness Stanislaw Galan, from a nearby village, who, with his wagon, was mobilized for work in the camp, stated, "I myself saw Oberscharführer [Translator's note: There is no one-to-one equivalency between U.S. military ranks and those of WWII Germany. Chroniclers conventionally leave the names of these ranks in the original German. Oberscharührer was a rank roughly somewhat higher than `Staff Sergeant.'] Munfeld grab a four-year-old little boy, lay him on the ground, stepped with one foot onto the child's leg, holding it down, and then pulling the other leg so as to split the unfortunate child in two. This I saw with my own eyes; the child's innards spilled onto the floor..."

After tearing the child apart, Munfeld tossed him into the oven. Then he petted his little dog.

When Munfeld left the camp to take a new, highly responsible post, he didn't take his little dog with him. He bade him a fond farewell and tossed him into the oven. Even here he remained true to his nature.

SS Man Theo Schollin, whom we have captured, had a very modest job in the camp: he was in charge of the storehouse. It was he who took the clothing from newly arrived prisoners. Then he examined them stripped. He told them to open their mouths. He had a special pair of nickel pliers, with which he extracted any gold teeth he found.

Before the war Schollin worked in a slaughterhouse: he was a butcher. Called into the army, he was immediately released, because Germany needed workers in its slaughterhouses.

In 1942, however, he was re-drafted and assigned to this camp. Now they needed butchers here.

Schollin stands in front of us now and weeps. He was captured. An SS man's tears! How loathsome those tears are!

Schollin did not weep much in former days. The Germans in the camp at Majdanek loved to laugh and play practical jokes.

Here is one of their "great" practical jokes: An SS man would come up to a prisoner, any prisoner, and say, "I'm going to shoot you right now!"

The prisoner would pale, but readied himself for the bullet. The SS man slowly took aim, first at the victim's forehead, then heart, as if deciding the best target. Then he would snap, "Fire!" A shot rang out.

The prisoner's body shuddered, his eyes closed.

The prisoner was struck in the head. He lost consciousness and fell. He came to a few minutes later, however, and saw German faces staring down at him: the one who had "shot" him, and the one who, unseen, had struck him from behind with a club.

The SS men were laughing so hard they had tears in their eyes.

"You died," they shouted at their victim, "You died, and now you're in the Great Beyond. And guess what? WE are in the Great Beyond, too! We, the Germans! The SS!

Yes, Hitler's fiends were convinced that heaven and earth both belonged to them.

All they had to do was exterminate half the population of Europe. Burn them in a crematorium.

They built the Majdanek camp with tremendous effort and energy over a period of three years. That was the first stage of construction.

The camp was built by the prisoners. They drained the mud and dug the pits and trenches.

They knew that they were building their own prison. Barracks in which to perish. Tangled barbed wire to prevent their escape. Gallows on which to hang. A crematorium in which to burn. The German system: Those doomed to die dug their own graves!

The camp grew on the bones and blood of the prisoners. They died while working, they died in the barracks. In the winter they froze to death. They dropped from starvation.

Every day during evening roll call, they were lined up for inspection. Those who could hardly stand were ordered to lie down on the ground. They lay down. They knew that meant death. They could no longer get up.

They lay there in the field all night. In the morning the dead and the still-living were dragged away by hooks, either to the crematorium or to be burned on pyres, Hindu style—a layer of wood planks, then a layer of bodies, a layer of planks, a layer of bodies...

Hauling the bodies of the dead was the job of the other prisoners. Anyone who refused to do so was shot on the spot. Conversations were short here in this extermination camp. Here human life was cheaper than a bullet. They killed you here with iron rods.

Prisoners were also sent to work in the crematorium. Those whose minds had become dulled or broken were preferred for this job. They were given generous amounts of vodka good long gulps. Drunk, muddled by the heavy stench of death, they bustled around the devil's ovens. They knew that within a month they, too, would make the trip to the oven. They were officially called "unreliable witnesses" by the Germans.

One way or another, sooner or later, they knew that the oven would devour them. There was no escaping from the camp. All they heard was "Hurry up! Move!" And they slaved at those cursed ovens, numbing their spirits with vodka.

Within a month all of them had been sent to the gas chamber and then... to the oven...

The insatiable ovens devoured everyone. The smoke poured out continually. In one day the five ovens incinerated 1400 bodies.

The Germans wanted to expand the camp. They dreamed of a gigantic death mill. If they had had their way they would have shoved all of Poland into the crematorium.

With a crushing assault, the Red Army put an end to the fiendish work of the cremation ovens.

The time had come for settling of accounts and retaliation.

Persons who entered the Majdanek camp ceased to be human beings. They became objects to be destroyed. They were robbed of

their valuables, their clothing. They were robbed of their names. Each was issued a tin number tag on a wire collar, which they had to wear around their neck at all times, and a striped prisoner's uniform. On the jacket of the uniform was painted a read, black or yellow triangle and a letter indicating the prisoner's nationality, "P" for Pole, "F" for French. Nationality determined the relationship of the guards toward the prisoner. Prisoners could forget their own names in the camp, but the guards never let them forget that they were a "Slav pig," a "Polish ox," a "Russian swine" or a "Jew."

With their tin number tags around their necks, the wire collar digging into their skin, the prisoners moved along their agonizing journey from quarantine to the crematorium. The journey could be very short. Or it could drag out over long months—months of slow, agonizing death. But it always led to Oberscharführer Munfeld's devil's ovens.

There was no escape.

Some convicts, who had been sentenced to hard labor in Italian sulfur mines, were sent to the camp. It is said that those sulfur mines are the most terrible places on earth, but the Italian convicts had survived them. Then they were sent to the camp at Lublin. Here they died quickly. The machinery of the Majdanek death factory cranked relentlessly, ruthlessly, inexorably.

It started with the quarantine.

New arrivals had to go through quarantine in the infirmary barrack for contagious tuberculosis. The twenty days of "quarantine" was sufficient even for the very strongest. They became acutely infected and carried the disease out with them to the common barracks.

In the single month of March 1944, according to data from German documents in the camp office, 1,654 people died of tuberculosis. These included 67 Italians, a large number of Poles, Russians and Czechs, as well as Albanians, Yugoslays, Greeks, Croatians, Slovenians, Serbs, Lithuanians and Latvians.

Tuberculosis was not treated in the camp. Here, instead of treatments there were beatings. But the camp infirmary was sparkling clean, especially for German press correspondents and photographers and for the constantly expected "international commissions" who, as it turned out, never came. On the doors were neatly printed signs such as "Pharmacy" and "Operating Room," even though there were not even the most basic medicines or rudimentary medical instruments in the camp.

On the other hand, these items were not really necessary. Among the prisoners the word was: Don't go to the infirmary. No one who went to the infirmary ever returned to the barrack.

If you wanted to prolong your life on this earth, you had to conceal any illness.

There was a medical scale in the infirmary. At times the prisoners were weighed. Germans love order. They very carefully recorded in a book: weight of an adult prisoner: 32 kilograms.

Thirty-two kilograms! This was the weight of the prisoner's bones wrapped in dry yellow skin.

The prisoners received a "soup" made of grass cut in the yard beside the barracks. With bitter humor, the Majdanek prisoners called the grass "vitamin SS."

More prisoners died of starvation than from tuberculosis. People dropped while working, and the SS men beat them with iron rods.

In their evening reports, the doctors did not mention the deaths that occurred during the day. The dead were not removed. The living lay on the same bed boards as the dead, even right next to them. The following day the living prisoners got the deceased's food rations.

A person imprisoned in the "extermination camp" could be killed by anyone belonging to the administration of the camp: potato patch supervisor Müller and the lowest-level prisoner crew foreman (kapo). The kapo competed with the SS men in terms of zeal. Killing prisoners was not considered a crime; on the contrary, it was proof of competence, it fell within the sphere of duty.

The SS men boasted in front of the Gestapo men about their heroic feats in the camp. The Gestapo men did the same thing.

Every SS man, every kapo had his own method of torture. One preferred to kick the victim in the throat with his boot, another liked to dance around on the victim's stomach. A thin, bony SS woman from the women's compound flogged women with a whip. She whipped them on their breasts, their genitals, their buttocks. Her whip

struck their bodies with a lewd swishing sound. A sadistic psychopath, she flogged women to death.

Among the SS there were also lovers of cruel jokes. Some set dogs on the prisoners, other amused themselves at the pool. They forced the prisoners to jump into the water, and when they surfaced, they were struck over the head with a club. If the prisoner did not drown, he was ordered out of the water and to get dressed. He had to dress in three seconds. If not, it was jump into the water again, again a blow on the head, again three seconds to dress... And so on, until the victims either died in the pool or dressed in three seconds. Obviously, in most cases they died.

Wladislaw Skowronek, a wagon driver, reports, "I saw with my own eyes a German SS woman bring six children to the crematorium, two little boys and four little girls. They were tykes four to eight years old. Munfeld, the chief of the crematorium, stripped them naked, shot them with his revolver and tossed them into the oven. I happened to see it because I was bringing some boards to the storeroom."

Reports Wieslaw Stopywa, "I saw what they did to my friend Czeslaw Krzeczkowski. He was 42 years old and a powerful man. But he was not standing straight in the lineup, so a Gestapo man started to beat him. He kicked him in the stomach with his boot... then with a rod... Then he jumped up and down on his stomach... But Krzeczkowski was still alive. He was a strong man. The Gestapo man grabbed a rod with a sharpened end and plunged it into Krzeczkowski's throat, then tugged upward and ripped his face. Krzeczkowski was still alive... His whole body was twitching. They put him on a stretcher and took him to the crematorium.

Piotr Denisov reports, "I saw an SS man kill a prisoner. I'm an engineer from Lublin. I was working in the camp laying sewage pipes. This SS man was guarding prisoners. He was a young guy, 19 or 20. He had a delicate, girlish face. I would never have taken him for an SS man. He singled out a young, strong Jewish fellow and ordered him to lower his head. The fellow obeyed. Then the SS man started beating him on the neck with a club. The Jew fell down. "Take him away!" ordered the SS man. They dragged him away, face down... over the frozen ground. There was snow on the ground, and it was stained with a trail of blood. But the Jew was still alive. So the SS man took a 60-kilo section of concrete pipe and threw it onto the Jew's back. And again, and again. I heard the horrible cracking of bones... and a scream. I started to scream myself. I didn't want to watch, but I couldn't force my eyes away. The SS man walked over to the Jew, opened his eyelid with the club... dead. Then he lit up a cigarette. And he had such a sweet girlish face!

It's not difficult to kill a person. All you need is an iron club. But you can't exterminate humanity.

That was precisely the maniacal idea that drove Hitler. Exterminate all humanity that he didn't like—the unsubmissive, the great of spirit, the freedom-loving. Or at least exterminate everything human in occupied Europe.

In order to accomplish this massive assault on humanity, the Germans needed gigantic, mechanized death factory complexes like the Lublin camp.

It's impossible to kill millions of people with automatic pistols. You need an enormous complex of all possible means of extermination known to man.

This is exactly what they built at Majdanek—a mass-production death factory.

Victims were shot in the forest, in the trenches. They were flogged to death with whips. Attacked by dogs. Bludgeoned with clubs. Their skulls were crushed. They were drowned in water. Stuffed into trucks and gassed—Pack `em tighter! Tighter! They died of starvation. They died of tuberculosis. They suffocated in gray concrete chambers, packed to the maximum. Two hundred fifty, three hundred—Pack `em tighter! Asphyxiated by Zyklon. Poisoned by chlorine. Observed through peepholes as they twitched and shook in their death throes. A new gas chamber was built. Asphyxiated. Burned on pyres. Burned in the old crematorium. Forced one by one through the narrow doors. Stunned by an iron rod on the head. Tossed into an oven. The dead and the living. The unconscious. Cram as many into the oven as possible—Pack `em tighter! Tighter! Bodies hacked to pieces. Watched through a blue windowpane as their bodies shriveled and incinerated. Killed singly. Killed in groups. Whole truckloads. Eighteen thousand at a time. Thirty thousand at a time. Assemble groups of Poles from Radom, Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, Jews from Lublin. Rush them through the camp. Surrounded by dogs and riflemen. Flogged with whips, Move! Move!

Long lines of Jews filed through the camp, to the fifth "field." Silently. In rows. Holding hands. Children clinging to their parents. Silently. Silently.—"Hurry up!" "Let's go! Move!" The Germans drove them on. The dogs barked. The whips hissed. The lines quickened their pace. The ones toward the end of the line pressed upon those in front. They ran. They stumbled. They fell. They lost their breath.

Suddenly all the loudspeakers in the camp began to blare. Lively foxtrots, tangos. The camp froze in terror. Everyone knew: today there will be large-scale executions. The tractor revved its engine. The rumba replaced the foxtrot.

In the fifth field the doomed prisoners undressed. Down to bare skin. Everybody. Men, women, children. They were forced over to the trenches. Move! Hurry up! They lay down in the trenches, body-tobody. Submissively. Resigned to their fate.—Tighter! Squeeze together! shouted the Germans. The people squeezed close together. They became entangled with each other. Arms, legs, heads no longer belonged to anybody. They existed separately, crushed, broken. Smothered. On top of the first layer a second. Then a third. The loudspeaker blared foxtrots. The tractor started to rumble. The whole trench was now filled to the top with a living, pulsing, groaning human mass, screaming at their executioners. The SS men sprayed the trench with automatic gunfire.

And all five ovens in the crematorium opened their greedy jaws. They were frantically overworked. Day and night. Fourteen hundred bodies every 24 hours. Not enough! They crammed more bodies into the ovens. Instead of six, they stuffed in seven bodies at a time. The temperature was increased. 1500°C. Not enough! They accelerated the incineration process. 45 minutes, 30, 25. The bricks in the ovens began to deform under the incredible heat. The cast-iron baffles melted. The crematorium's smokestack ceaselessly spewed out its billows of ashes. The black stench of death permeated the camp.

The wind blew the foul odor over the entire surrounding area.

Was it possible to survive the death Camp?

Some sought death themselves, to shorten the terrible agony. They threw themselves against the electrified barbed wire and died, blackened and contorted.

Engineer Denisov told us of another case of voluntary death: Two prisoners approached an SS man and asked to be hanged. "Hang us!"

The SS man looked at them with surprise and smiled.

"Sure. Be glad to."

He tied a noose, put it around the neck of the first one, placed him near the trench, gave the ends of the rope to two helpers and, telling them to hold on tight, he struck the prisoner in the back of the knee. The prisoner fell into the trench, trembled a few times in the noose and expired.

Immediately the second prisoner walked up to the trench. He loosened his collar, put the noose around his neck, lunged forward and followed after the first prisoner.

On a barrack wall we found scribbled, "Vanya Ivanov tried to kill himself and failed, and it was his own fault." Someone else, as if responding to the first, wrote, "If one could only die in such a way that one's death would bring some good!"

Was it possible to escape from the camp?

We heard of the "mutiny of the shovels" and of the "escape of the eighteen." Both of these actions involved Russian prisoners, and what they illustrate most of all is the Soviet Russians' spirit of dedication to the struggle for freedom.

The "mutiny of the shovels" took place in the Krebecki forest, where a group of Russian POWs from the camp were working. Seventeen Russians killed the German guard with their shovels and escaped.

The "escape of the eighteen" happened later. It was preceded by an actual meeting in a barrack. Question: to try or not to try an escape. Eighteen opted to try, fifteen opted to stay.

The eighteen decided to flee during the night. Those who remained promised not to betray them, and did riot. Throwing five

blankets over the barbed wire entanglements (which were not yet electrified at that time), the prisoners climbed over them and escaped.

That same night the Germans took the remaining fifteen out of the barrack and shot them.

I know of one more case of an escape. It was a Jew from Lublin named Dawidson. He escaped at the moment when they were being taken out of the camp to work. He knew that if he tried to escape they would shoot him. But he also knew that they would shoot him if he didn't try to escape. He didn't have much of a choice. He took off running, expecting a bullet in the back of his head. But the bullets missed him. He got away.

A Polish family who knew him gave him shelter. For two years and thirty days—until our armies marched into Lublin the Poles concealed the Jew in their attic and fed him. The entire two years and thirty days he crawled around so that no footsteps would betray him or the family that was concealing him. For the entire two years he never saw anyone, didn't talk to anyone. They brought food to him in the attic, and that was all. He forgot how to talk. He got used to no daylight. But he survived. We saw him.

And, just like him in his attic, thousands of people in the camp also lived with uncertain hope...

On a barrack wall in the camp we found a drawing made with a blue pencil. No signature. No words. The drawing was that of an ordinary Ukrainian landscape. How much bitter longing that picture held, for home, for freedom... how much hope!

Thus, even here in the death camp, people didn't lose hope... And they placed their hope in the Red Army.

And the Red Army didn't let them down.

Nowadays thousands of people from Lublin come to Majdanek. They come to look at the dreadful camp.

For three years it was a nightmare for them. For three years they had breathed in the foul odor of the camp's ovens. For five years they lived under the Germans' whip.

The death camp had been enveloped in foul stench and secrecy. Now there are no secrets. Here are the devil's ovens. Here are the trenches where the prisoners were shot. Here are the remains of the half-charred bodies in the crematorium.

The people look and do not weep. They have already wept all their tears—there are no more. The crowd cries out.

Germans are working in the trench. They were captured in the camp. The butchers have been ordered to dig up the bodies of their victims.

Their shovels strike the earth with a hollow sound. The Germans work silently. They merely tremble with fear at the furious shouts of the crowd and lower their heads toward their shovels.

The crowd cries out.

The shovels strike the ground. A woman screams in horror. A little child's foot protrudes out of the lumpy clay mass.

"Murderers!" the crowd shouts, "Murderers!"

They bring German captives, soldiers and officers, up to the site. There are over eighty of them. To protect them from the anger of the crowd, they are led to the other side of the trench. Their guards point to the work of their hands. The child's body is pulled out and lies beside the remains of others.

The Germans approach in silence. Some turn away. Others look at the body blankly.

"Bandits!" the crowd shouts, "Murderers!"

The crowd grows. From the highway, from the surrounding villages they come. Only the trench separates them from the butchers. In the trench amidst the remains of the victims is the body of a child.

The Germans walk with their heads down, their eyes to the ground. Their arms behind them. The crowd is furious. There is no hissing whip to scourge them as they shout, "Murderers! Degenerates! Sadists!"

An elderly Pole waves his cane above his head and shouts, "How, how will you pay me for my son? How?"

And again the wind taps on the windows in Majdanek: Remember the devil's ovens, Pole, remember the camp of death! Remember the millions of tortured, shot, burned! Remember and take revenge!

|

.gif)