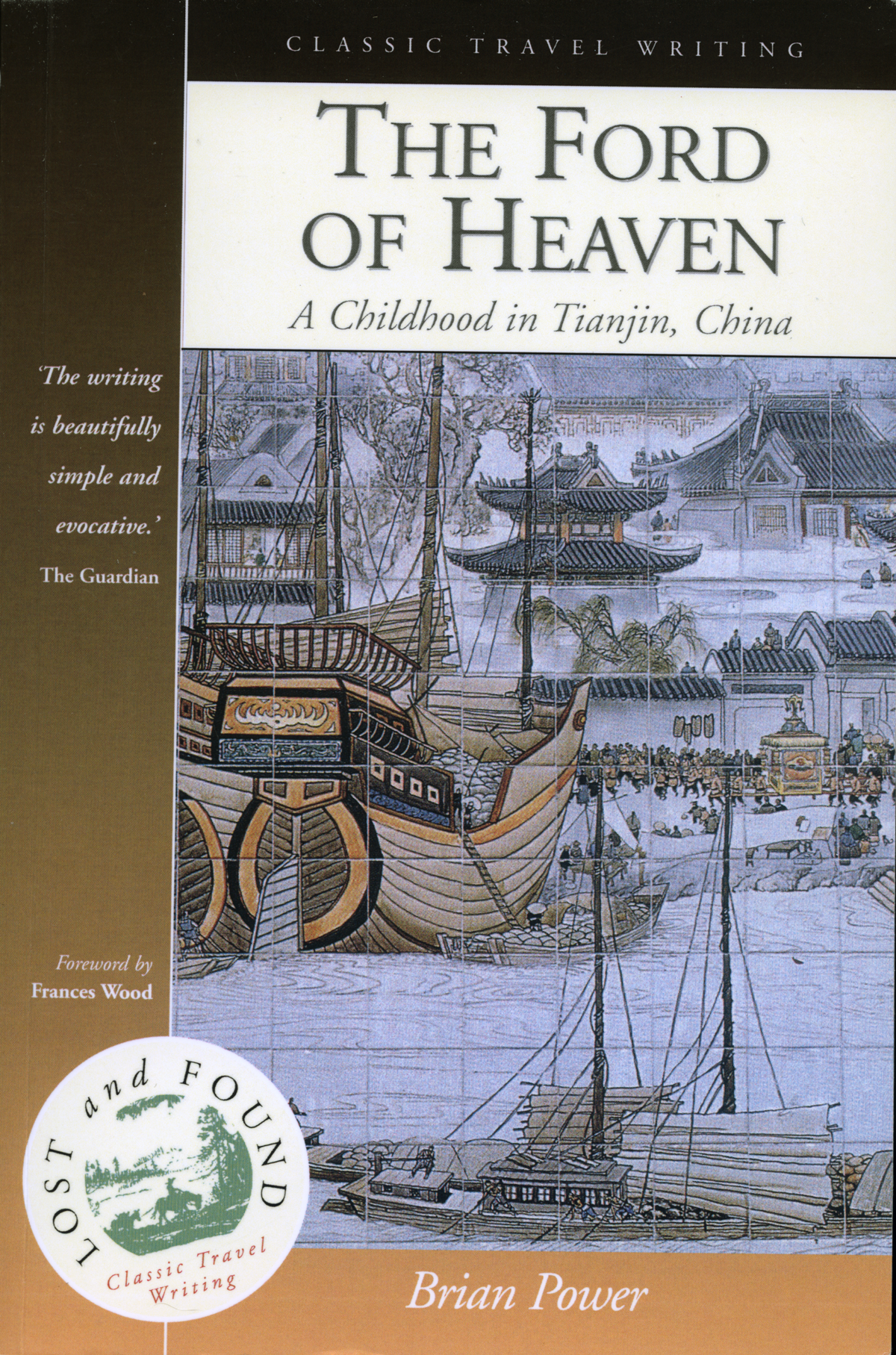

"THE FORD

OF HEAVEN"

by Brian POWER

CLASSIC TRAVEL WRITING

Looking out to sea I whispered a farewell prayer to the wind: Help me to be content to pass by even the most beautiful places without wanting to remain in them for long or to keep them for myself'

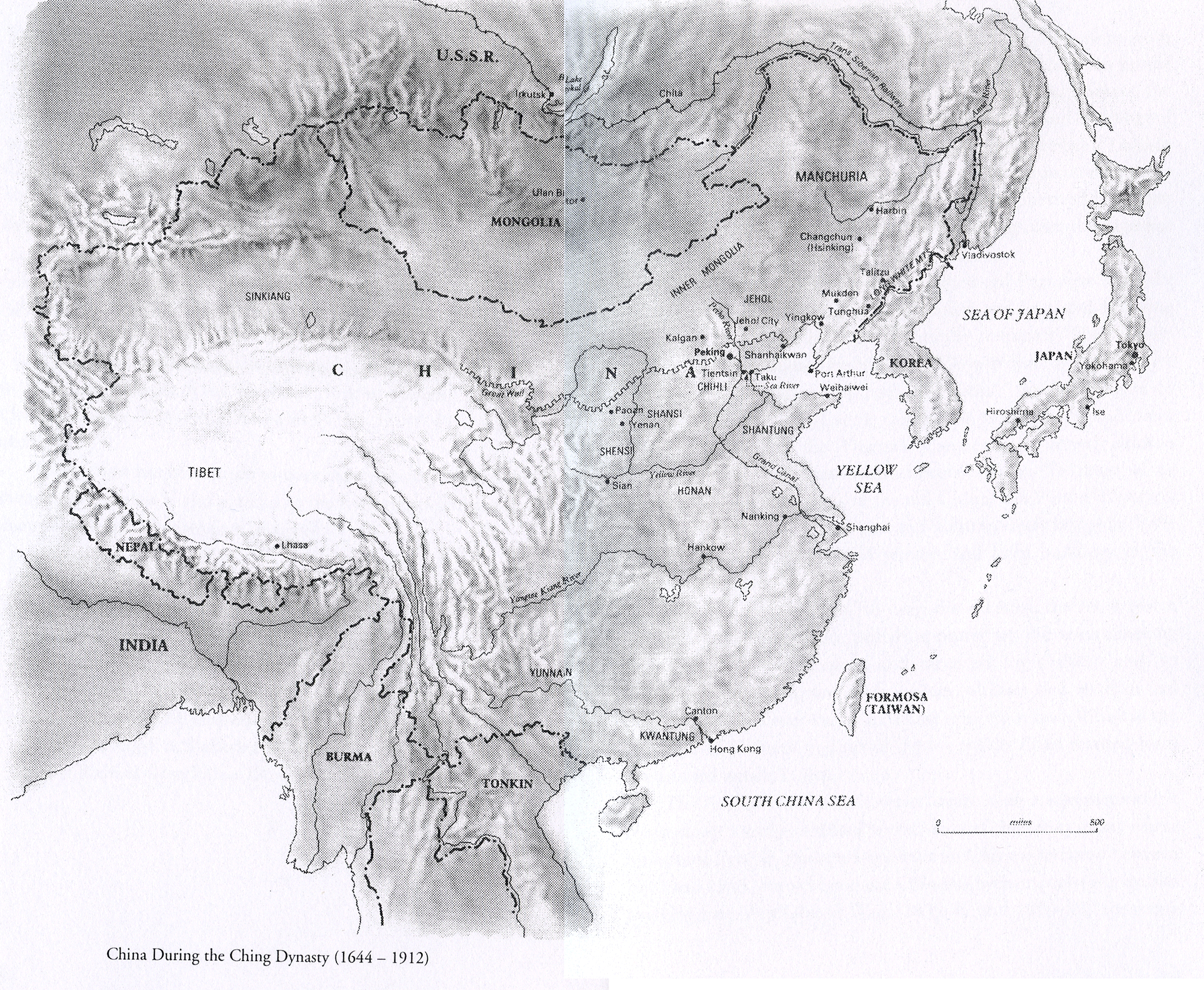

The Ford of Heaven, an ancient river port in north-eastern China, gave travellers access to the Celestial City of Peking eighty miles to the west, where the Emperor ruled by the mandate of Heaven. Tientsin, as British settlers called it, became a treaty port in 1860 in the wake of the Opium Wars. In the 1920s and 1930s it was occupied by Britain, France, Germany, Russia, America and other foreign powers. As rival war-lords fought for control, the elusive White Lotus society plotted, and Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists vied with the `Reds', the old order was soon to be swept away.

This memoir evokes a childhood spent in this strange and exotic place. In contrast to other accounts of lives lived in foreign enclaves, Brian Power's early experiences were shaped not by his parents' values but by the loving care and calm spirit of his Chinese amah, Y Jieh, who gave him the gift of Chinese and an understanding of her people's legends and superstitions. The world that Power evokes is a microcosm of the complexity and ferment that was China before the Second World War, yet seen through the fresh eyes of a sensitive child attuned to the lives of the people around him.

This new edition of The Ford of Heaven (first published in 1984) contains a new foreword by Frances Wood, Curator of the British Library's Chinese Collection, as well as a postscript and extensive additional material by the author.

'His memoirs are delicate, animated, firmly fleshed and unforced.' ... The Observer

Brian Power was born in Tientsin in 1918. He went to England to study in 1936, intending to return to China as a teacher, but war and revolution prevented his return for nearly forty years. He is the author of The Puppet Emperor (1986), the story of the last Chinese Emperor.

FOREWORD

Few books have the power to take you back to a place with immediacy. The Ford of Heaven is remarkable, for it conjures up the bright blue skies of northern China, the smell of the markets, the sound of the street calls and the appearance of the grand buildings of the treaty port of Tientsin. Though Brian Power describes a Tientsin that has vanished politically, the solidity of its architecture and the strength of its traditions revealed how they had survived long after he had left for university in England and long after the Japanese invasion and the Chinese Communist takeover.

I first went to Tientsin in 1975 when red flags flew from the roof of the Kailan Mining Administration building, and Kiessling and Bader's Café had been democratically re-named The Tientsin Canteen'. Nevertheless, the streets of Tientsin were still lined with gloomy bank buildings of rusticated stone; the battlements of Gordon Hall still stood stark against the sky opposite the Astor House Hotel, and the Tientsin Canteen still served chicken stroganoff and ice cream with chocolate sauce. To those of us privileged to see such parts of the old China, The Ford of Heaven is a magical reminder of things past and it immediately brings back the pre-pollution blue skies, cold winters and lofty buildings of the Tientsin we knew.

After the death of Mao Tse-tung, the old street traders of North China began to call again, pedlars appeared on the streets making toffee silhouettes of dragons and monsters for children and, in Peking, flocks of pigeons with aeolian whistles tied to their tail feathers hummed over the lanes. These reappearances testified to the resilience of Chinese traditional culture which Brian learned from his devoted amah, Yi Jieh.

The Ford of Heaven is, however, more than a reminiscence. It conjures up a truly vanished world, that of the treaty ports where Europeans lived in protected enclaves on Chinese territory between 1843 and 1943. Forced upon the Chinese government by the treaties resulting from two Opium Wars (1839-42 and 1856-60), the treaty

ports were foreign settlements, set up in an increasing number of Chinese cities, where foreigners lived charmed lives, protected from the outside by gunboats, foreign troops and immunity from Chinese laws.

For many treaty port inhabitants, it was a time of great privilege. They had servants, imported food and perhaps more comforts than they could have afforded at home. At the same time, the treaty ports were tiny claustrophobic circles. Yet the smallness of the enclave meant that Brian, an acolyte of the College of the Jesuit Fathers on Racecourse Road, once took Père Teilhard de Chardin home for tea. Teilhard de Chardin, a fine scientist and radical theologian, became one of the most celebrated Jesuits of his time, but in Tientsin, he was one of a tiny circle of foreigners, available for tea-time conversation.

Not all of Brian Power's acquaintances were so grand: there was 'Mad Mac' the piano-tuner, who adjusted the multiple pianos of the 'Christian General' Feng Yu-hsiang (one of which was kept aboard his armoured train) and who described the majestic Gordon Hall, laid out in memory of General Charles Gordon who, much to Queen Victoria's sorrow, died at Khartoum, as looking like a lunatic asylum on the outskirts of Edinburgh, and sad-faced Herr Schneider who played the violin at the Empire Cinema and at Kiessling and Bader's Café.

Though there are many accounts of treaty port life in China, Brian Power's is unusual in that he remembered Chinese friends. These are conspicuously lacking from Shanghai memoirs which reveal the class-conscious and race-conscious nature of the foreign settlements there. Perhaps Tientsin was unusual for others, like the son of the harbour-master at Taku, also remembered Jimmy Ni, a fellow-pupil at the British School, who lived in a half-Chinese, half-foreign house.

If one of the shocking aspects of many treaty port memoirs is the absence of Chinese friends, by contrast, one aspect that emerges from almost all is the enduring attachment to a Chinese amah or nanny. Horror stories about nannies in England abound: Nancy

Mitford was mistreated by one of hers and even the Duke of Windsor was regularly beaten with a hairbrush by his, but all those who were brought up in China remember their amahs with great

affection.

Brian Power's Yi Jieh was the foundation of his life as a child. When his elder brother disappeared (temporarily), when his baby sister died of meningitis and when his mother collapsed, Yi Jieh was always there. More than that, she took him into her world, telling him Chinese stories, helping him understand what was going on in the market and, through her eyes, the world outside: she was the ideal companion. When she saw him off in 1936, she pressed her hard hands to his cheeks and he suddenly realised he might never see her again. True to her practical and loving nature she reminded him to buy apples for the trip.

One wonders what the bereft amahs felt, for surely the perceived affection and care for their small foreign charges was genuine. Despite the official disapproval of the treaty port era, many of us have been touched by the memory of ancient waiters, anxious to help, who spoke a `Chinglish' that dated back to that time. In Brian Power's beautifully written memoir of a real place and a real past, we can recapture some of the humanity that lay behind the politics of the past.

Frances Wood

INTRODUCTION

In northern China the Sea River flows through a town on its way to the Yellow Sea. Once this town had been on the coast and the waves of the sea had surged up to its oldest building, a lighthouse. But over the years the sea had retreated. By the late nineteenth century, when the decadent Manchu dynasty was nearing its end, the sea had withdrawn forty miles to the east, leaving behind a plain of mudflats and salt marshes. Through that plain the Sea River twists and turns like a serpent in search of its old lair.

Many waterways meet at the stranded inland port. Three tributaries of the Sea River, heavy with silt after descending from the high plateaux of the Interior, converge here. Here, too, the Grand Canal, built by the Tang emperors before 800 AD, ends its long journey. For dynasty after dynasty the barges carried the imperial grain tax along that artery from the distant paddy-fields of southern China to the barren desert and salt marshes of the inhospitable north.

Eighty miles to the west lies the Celestial City of Peking where the emperor, the Son of Heaven, reigned. Because the old port at the meeting of the waters gave travellers a way across them to the Celestial City, it was called Tientsin, the Ford of Heaven.

A maze of narrow creeks links the Sea River and the Grand Canal with the coastal marshlands where the nomadic boat-people lived. That mist-shrouded region was also the haunt of pirates and outlaws. At times of calamity, such as drought or flood, they raided Tientsin where they plundered the granaries.

Peasant risings, usually inspired by one of the ancient secret societies, had always been a threat to Tientsin. The professional storytellers who roamed those parts would recite the history of the famous rebellion when Chu Yuan Chang, a poor peasant who had become a beggar monk, led a peasant host against the Mongol emperor. Having seized Tientsin, the rebels crossed the Sea River in 1368 and drove the imperial army from Peking. Thus ended the Mongol domination of China which reached back a hundred years to the time of Khubilai, grandson of Genghis Khan.

The victorious peasant leader became the founder of the Ming or 'Light' dynasty (a word taken from the creed of the secret society of the White Lotus which praised as virtues the `light' elements of nature: sun and moon, quickening fire, clear water and searching wind). It was said of the first Ming emperor that he would never allow officials to come between him and his peasant subjects.

The Ming dynasty lasted for nearly three hundred years until, in 1644, a traitor let the Manchu cavalry through a gateway in the Great Wall and the alien Manchu family of the Ching usurped the imperial throne.

Unlike the Mongols who went before and the Manchus who followed, the Ming emperors were Chinese. A nostalgic loyalty to the Ming lingered on among the people of northern China. That loyalty was kept alive by the story-tellers. They had a saying that the founding of the Ming dynasty was the first springtime; there would be a second spring when the Manchus were driven out and the Ming restored.

Four hundred and fifty miles south of Tientsin flowed the Yellow River. Between 1851 and 1853 it changed course dramatically, forming a new estuary within a hundred miles of Tientsin and flooding a vast area. People took this disaster to mean that the Mandate of Heaven was about to be removed from the feeble Manchu emperor in Peking. At Tientsin rebellion was in the air. The characters 'Restore the Ming' were daubed in white on the high stone wall which defended the town. In 1860 large numbers of destitute peasants were reported to be gathering in the marshlands. One rumour warned that an attack on Tientsin would come in the first quarter of the harvest moon. But, before the peasants and their outlaw leaders could make their move, they were overtaken by another invader. The first quarter of the harvest moon had not yet begun when, belching black smoke, foreign gunboats steamed up the Sea River.

After the gunboats came the traders and the missionaries. By the turn of the century foreign settlements protected by troops, those of Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Belgium, Russia, America and Japan, were established at the Ford of Heaven. The second spring was not yet to be.