- by Meredith & Christine Helsby

Chapter 6

[excerpts]... FOOD

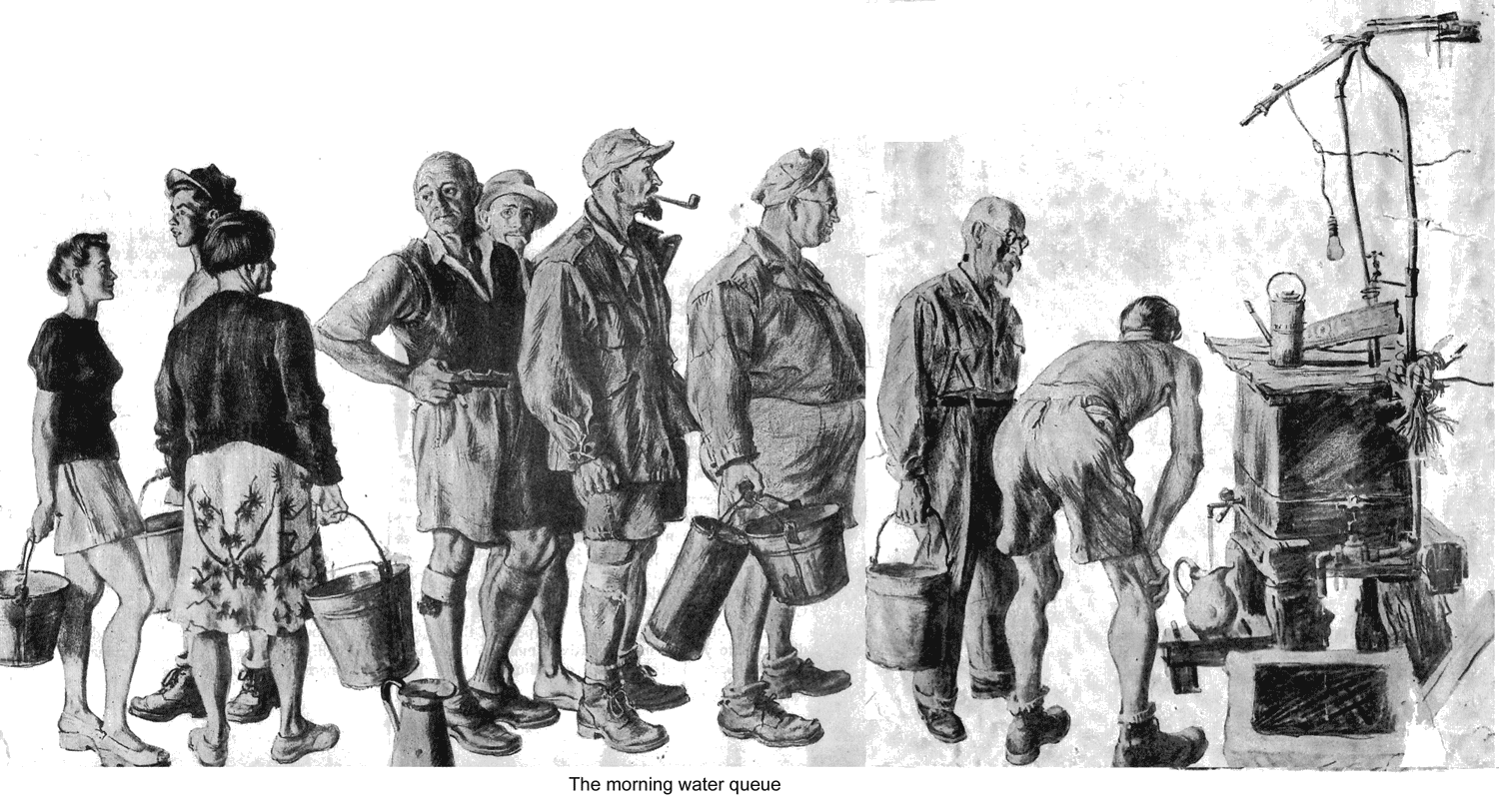

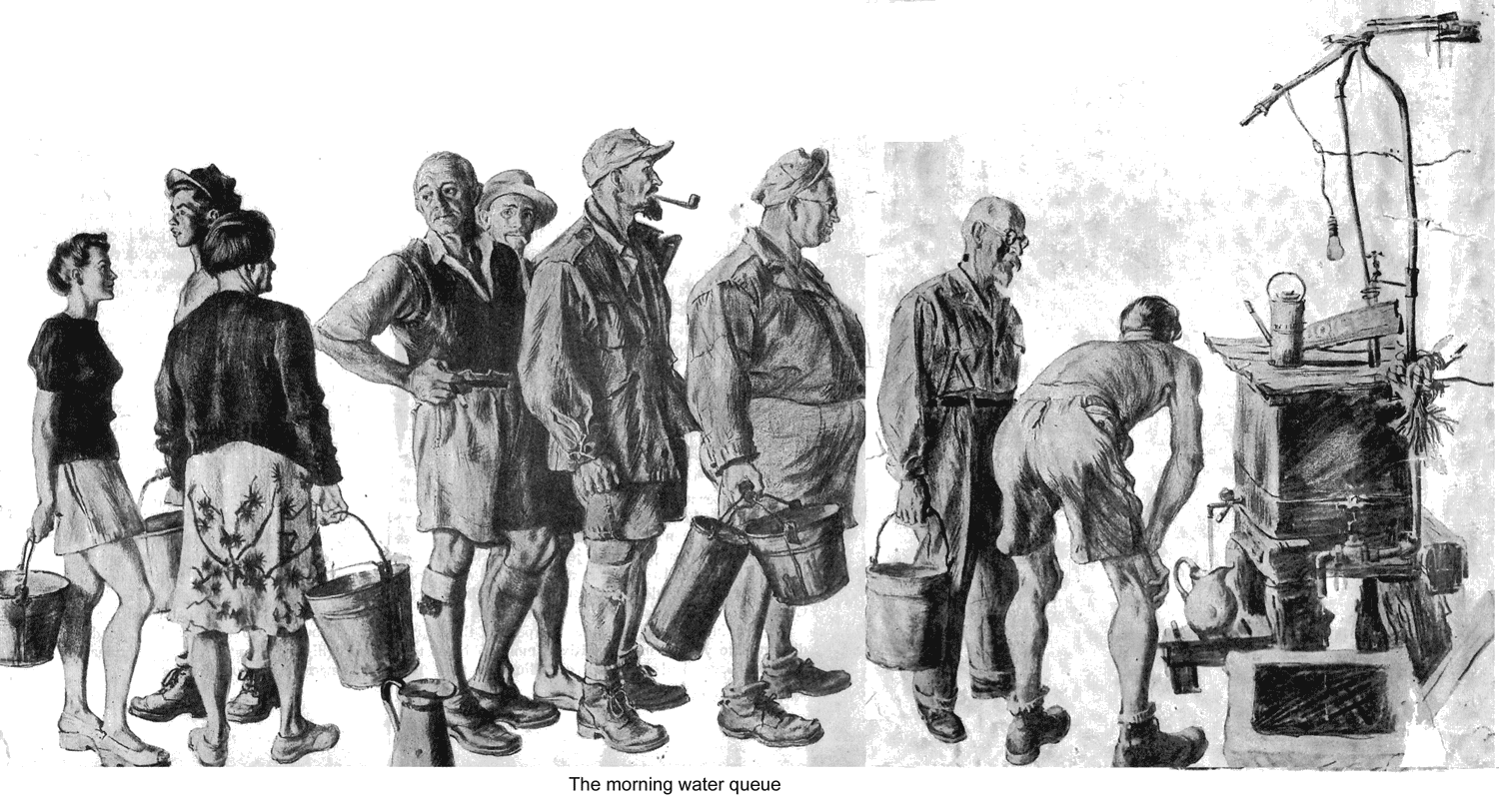

ur first meal when we arrived in Weihsien that bleak night in March, 1943, was a single dish, a most unappetizing soup consisting of pieces of fish — heads, tails and all mixed with stale bread and salt, in plenty of water.

ur first meal when we arrived in Weihsien that bleak night in March, 1943, was a single dish, a most unappetizing soup consisting of pieces of fish — heads, tails and all mixed with stale bread and salt, in plenty of water.

Once the kitchens got organized and our cooks were trained, the fare improved somewhat.

Since our camp was not located in a war zone, supplies of grain, vegetables and sometimes pork, beef and horse meat were obtainable from Chinese merchants by the Japanese. Thus, we did not suffer the near starvation so common in other P.O.W. camps in Asia.

As the war progressed, however, supplies dwindled and hunger was a constant companion. Food became an obsession. “A conversation on almost any subject,” one internee remembers, “would eventually get around to food.” A favorite game was, “If you could go into a restaurant and order anything at all, what would you like?” One young missionary recalls that his favorite fantasy was going to a Howard Johnson’s and ordering juicy hamburgers and copious quantities of milk shakes.

Food became an obsession. “A conversation on almost any subject,” one internee remembers, “would eventually get around to food.” A favorite game was, “If you could go into a restaurant and order anything at all, what would you like?” One young missionary recalls that his favorite fantasy was going to a Howard Johnson’s and ordering juicy hamburgers and copious quantities of milk shakes.

“Give us this day our daily bread” took on new meaning in that our diet consisted largely of bread, a commodity that for our first year in camp was not rationed. With more than enough flour for the daily bread supplement, the cooks also made noodles and dumplings. In October, 1943, I mentioned in my journal that Dr. Anderson, a professor in a China university, estimated that 83 percent of our nourishment came from white flour.

Along with bread, however, there were supplies of Chinese grains. Although we virtually never had rice we did receive millet occasionally, as well as a coarse sorghum-like grain called “kaoliang” which the Chinese grew primarily to feed pigs. Since any food could be made to go further by watering it down, our menu was replete with soups, stews and porridges.

A typical day’s menu in camp was as follows: Breakfast — bread, porridge consisting of leftover bread (usually stale) mixed with water (no milk or sugar), “lu tou” (very small dried green Chinese beans) or kaoliang; Lunch (our main meal of the day) — usually bread and stew (generally referred to as SOS — “same old stew”). Now and then there was relief from the stew, in an occasional “dry meal” consisting of some kind of meat, fried potatoes and gravy.

Supper ― soup and bread.

Each internee was entitled to a ration of about one tablespoon of sugar a week. By common consent we agreed that the entire allotment be turned over to the cooks, who could then occasionally furnish us with a dessert of inestimable delight. We cherish memories of these culinary oases in those bleak deserts of dietary sameness. From the bakery came such creations as shortbread, gingerbread, even cakes. Amazingly, wedding cakes were baked for all three of the weddings that took place in camp. These were wondrous concoctions to us, though looking back, I doubt that they bore much relationship to modern America’s tiered masterpieces.

Attempts were made in a variety of ways to find additional nourishment to supplement our diets. Some discovered weeds growing around the compound which when cooked resembled a coarse spinach. Eggs, though later obtained through the black market (more about this later), were at first a rarity. Sandra, along with the other children, was allotted about two eggs a month or as the Japanese could obtain them. To prolong the pleasure and nutrition of these treasures, Christine fashioned a concoction by mixing the egg with “tang shi” (kaoliang molasses). Used as a spread to top our bread, the food value of that egg could be extended several days.

To supplement the bone meal which we brought into camp (but ran out of almost a year before we were freed), we pounced upon eggshells discovered on a trash heap, dried them for days on our window sill, then rolled them as finely as possible with a glass. Sandra consumed about a quarter teaspoon mixed daily in her food. (Her adult teeth are now as strong and beautiful as any whose childhood was spent in “replete” America.)

There was a critical need for milk, especially for small children. When the commandant was appealed to, surprisingly he arranged to have a quantity of milk brought regularly into camp. This was properly sterilized in the hospital kitchen and distributed to children under three years of age, enough for each child to have about a cup of milk daily, though not available every day.

As we entered 1944, food supplies progressively dwindled. Bread was rationed to two slices a meal and the quality of food likewise deteriorated. What meat we got was half rotten and of questionable origin, generally thought to be either mule or horse. The variety of vegetables was reduced to cabbages; large, coarse, unpalatable, waterlogged white radishes; and supplies of egg-plant, which when cooked turned into a repulsive purple mush without seasoning except a bit of salt.

Everyone lost weight. Those who came into camp overweight lost as much as 100 or more pounds. Some weighing 170 or 180 were soon dropping to 125 or lower. Though we were not starving, with the interminable progression of the war and the prospect of repatriation an ever-receding mirage, the specter of serious malnutrition loomed before us, large and threatening.

In Chapter 11 Christine describes our last Christmas in camp when she was in the hospital. It doesn’t seem “fitting” in that part of the story to speak of food, so here she adds a line or two while we’re on the subject:

While talking about Weihsien meals and menus, I can’t help but recall what was to me the most impossible, most inedible portion set before me during our almost four years of prison life. And in my state ingesting it was not an option but an absolute “must.”

The doctor had earlier said that I could probably leave the hospital by New Year’s Day but that was not to be, for in my weakened condition I had now contracted typhoid fever which, in the end, meant almost a three-month stay.

The typhoid began with days (and nights) of high temperature and chills. I shook so hard that the patients in beds on either side of me couldn’t sleep because I was shaking their beds too. Then I lapsed into a coma which lasted about two weeks. When I came to, the doctors were in an almost constant huddle, trying to find something I could eat — not that I wanted anything. For once I was not hungry. Of course, there was no hospital equipment for I.V. feeding so what I got by way of nourishment was simply whatever they could give me by mouth.

Regular camp food was definitely too coarse since it irritated the myriad of tiny sores covering the inner lining of the intestines. This did not particularly trouble me since I had no appetite anyway. But the doctors, of course, knew they had to get some kind of food in me, and quickly.

What they came up with was corn-starch, a food sufficiently bland for my organs to handle. So cornstarch — thick, gray blobs of it became my daily menu. It looked just like the glop my mother used to cook up for Dad’s shirt collars! That was it, three times a day for three weeks. I really struggled with it. The taste and look of it was equally revolting. The staff ― bless their hearts, worked diligently to find an incentive to help me get it down. Somebody thought of the inducement of giving me a level teaspoon of sugar on “the blob,” for one meal, every third day! This was long before Mary Poppins’ “A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down.” So I ate — so I lived.

In the meantime there were other concerns. First, my hair! It was coming out in bunches. If I’d had my wits about me, I’d have said, “Shave it!” (Then maybe it would have come back in, curly!) But since I couldn’t sit up, they just rolled my head around on the pillow and snipped it off, leaving two-inch tufts all around.

And then, it seems, I was developing a different strain of typhoid. I was covered with a rash from the soles of my feet to my scalp.

Not an inch of my body was clear. This meant that all the doctors in camp wanted to see me. They stood in line outside the screen around my bed, awaiting their turn and discussing my symptoms.

This extra attention I could handle except that I was very weak and soon tired of trying to answer their questions. But most tormenting of all was the itching, all over and all at once. The nurses were sympathetic but could offer no medication that would help. Their best solution was pai kan — a cheap Chinese wine which left me positively reeking. This did not make me the most popular patient in the ward! The pai kan did, however, soothe the infuriating itch.

The benefits, though, quickly wore off so I often begged for another “dunking.”

But, thanks to my Father’s healing hand and all the loving care of my fellow internees, I survived. I left the hospital on March 8, and it was so good to be home with Meredith and Sandra in our little 9 by 12. My weight had dropped to 93 pounds, and with my less-than-petite frame I looked a bit gaunt. But we were together, and though we didn’t know it then we had less than six months to freedom.

Meredith continues:

Blessed supplements to dining hall fare came on occasion from three sources. Comfort money, which was advanced to us at intervals through the Red Cross (I’ll speak more of that later), could be spent in the canteen, a small shop which periodically carried limited quantities of food stuffs. We were especially grateful for Chinese dried dates (which gave a bit of the sweetness we so much craved), peanut oil, and sometimes a ration of peanuts which we made into a chunky spread for our bread. Once, however, we were mistakenly sold fish oil which tasted much like cod liver oil. With this we spoiled three rations of peanuts we’d been hoarding to make a spread. But, of course, we ate it.

Secondly, on occasion, internees were permitted to receive packages. The arrival of Red Cross parcels was, apart from word of war’s end, the most exciting news ever received in camp. These beautiful cardboard-encompassed bonanzas were supplied by the American Red Cross.

These magnificent gifts measured almost 3 feet long, 1 foot wide, and 18 inches high and weighed 50 pounds. Inside was a treasure trove of incredibly wonderful things: a pound of powdered milk, four small tins of butter, three of Spam, eight ounces of cheese, sugar, two four- ounce tins of powdered coffee, jam and a small package of dried fruit — either raisins or prunes — and four packs of Lucky Strike cigarettes.

So prized were these marvelous gifts from heaven that one internee wrote, “To each of us, this parcel was real wealth in a more basic sense than most of the symbols of wealth in civilized life. No amount of stocks or bonds, no Cadillacs or country estates, could possibly equal the actual wealth represented by this pile of food, for that food could prevent hunger for four months. A Red Cross parcel made its possessor an astoundingly rich man.”

Mixed in with the food was a considerable complement of men’s clothing. Curiously, however, although there were supplies of shoes, underwear, shirts, even a few coats, we never received any trousers. This gave rise to some amusing remarks, particularly from the Britishers, one of whom remarked, “Doesn’t anyone wear pants in your country, old boy?” But Christine wondered why the men complained because they had no trousers, while the women internees never received a single piece of any kind of clothing.

These parcels came from the American Red Cross and were designated for American prisoners of war. Needless to say when these blessed bundles arrived, we were often the objects of envy by the many non- Americans in the camp. For the most part, however, American internees made it a point to share the contents of the packages with their non-American friends and neighbors.

Later, we received a load of smaller packages from the U.S. Red Cross — and this time there were enough for everyone to have one.

The third means of quelling hunger pangs came from food from Chinese merchants, in a secretive and strictly illegal “over-the-wall” enterprise in which I figured as one of the leading camp entrepreneurs. In most penal systems throughout the world an amazing amount of commerce is carried on between prisoners and the out-side world. In this respect, Weihsien was no exception.

With our poor diet and need for a variety of commodities unobtainable in camp, there was powerful motivation to make contact with local Chinese merchants. By nature the shrewdest business dealers on earth, our Chinese friends saw in this an opportunity for mutual profit.

During the early days of camp, the general disorder and lack of vigilance by the guards, and the fact that the compound wall was topped with but a single strand of barbed wire, provided opportunity for contact with enterprising merchants. These men would stand outside the lightly guarded barrier, informing us that for a price they could supply us with everything from sugar and condensed milk to eggs (our all-important source of protein). In this way, I made the acquaintance of merchant Han.

I did not lightly embark on my career as a black marketeer nor without some initial pangs of conscience. Contact with Chinese, I knew, was strictly forbidden. And trading across the wall was clearly in defiance of camp rules.

Still, as we faced the daily struggle for survival, I came to believe that it was more my moral duty to use means at my disposal to relieve suffering and save human life than to adhere to the laws imposed upon us by our captors.

--- James H. Pyke records in White Wolves In China (page 143, printed in 1980 as a memoir of Fred and Francis Pyke) that “the difference between survival and disease or starvation was the operation of the black market. Fred Pyke was a very moral person, punctilious about right and wrong, but he worked on the black market chiefly because of 450 children in camp. Their whole lives would have been affected without proper nourishment and the black market did provide peanuts and eggs.” ---

Thus, the “Helsby Company” was formed and my over-the-wall marketing activities begun. My partner in this crime of benevolence was Hilda Hale, a mother of two daughters whose husband in prewar days was head of Cook’s Travel Service. She was my lookout, and her room served as a temporary warehouse for the stashing of our goods.

One may wonder at this point what we used for currency in these transactions. A word of explanation is in order. According to regulations of the Geneva Convention, civilian P.O.W.s were to receive the equivalent of $5 a month, designated “comfort money.” These funds came from the Swiss Consul and were intended for the purchase of toilet paper, toothpaste, sundries and occasional food items obtainable from the camp canteen which was operated by internees under Japanese supervision.

For the three Helsbys our allotment came to a fairly generous $15 a month. Unfortunately, however, squabbles between Japanese and the Swiss government over rates of exchange impeded the flow of this allowance. We seldom received comfort money two months in a row, and at one point went six months with-out a payment.

Another problem soon developed — inflation. The FRB (Federal Reserve Bank) currency, in which we received our comfort money, had a fairly stable 4 to 1 U.S. dollar value in 1943. By 1944, however, it had been devaluated a whopping 600 percent. The slight increases in the comfort allowance never began to keep pace with this galloping inflation.

At first, over-the-wall business was done with FRB dollars, but when money ran out the merchants incredibly agreed to take promissory notes in both U.S. and British currency, to be paid after the war. Toward the end, watches and rings were bartered.

In our black-market business, our confederates were Chinese coolies who regularly came into camp to empty cesspools, haul away garbage and do menial tasks. Acting as couriers they would secretly carry notes and orders for goods back and forth between internees and Chinese merchants. At other times, they would actually carry into camp large quantities of goods concealed in the big metal “kangs”

My contact point with Han was a felicitous jog in the compound wall immediately in back of the guard tower and not a stone’s throw from our barracks, room No. 14/7. By climbing up on the drain pipe I could peer over the 12-foot wall and on occasion speak directly with him.

Once I had taken an order for eggs, sugar, milk and other commodities from my fellow internees, I would laboriously write the aggregate amounts in Chinese characters and convey the memo to merchant Han.

By a coolie go-between, he would inform me of the time of delivery. Our preference was a dark, moonless night or times of inclement weather, when we knew the guards would be less vigilant and we would be less likely to be seen or heard.

At the designated hour, I would slip quietly along the wall to the rendezvous point with Hilda keeping watch. A low whistle was her signal that a guard was approaching.

A knock on the wall told me that Han had arrived. My response was “Wei Wei” (yes or hello) to which Han would reply “Laile Laile” (I’ve come, I’ve come). At this point I would slip my money over the wall into his outstretched hand. Then in a few minutes I would see his men begin to materialize from behind the grave mounds in the adjacent field. Hastily now the goods were hoisted in wicker baskets atop the wall and slid under the barbed wire into our waiting hands. Fearful of being caught with any of this store of goods in our rooms, we delivered the supplies to our buyers as quickly as possible, often within minutes of the time we received them. If some things remained for daylight delivery, Christine, holding anything but eggs under her jacket or coat, could get past the guards with less suspicion.

Two cardinal rules we adhered to from the outset: we never did business in either liquor or cigarettes nor did we personally profit from the exchange, charging our fellow internees exactly what we paid merchant Han.

We were but one of several “companies” engaged in this important enterprise. Most notable perhaps was “Wade and Company” who operated at the south end of the compound. They did a brisk business, not only in eggs, but also in pai kar (a kind of rice wine) and other spirits in great demand by many in our community. Wade’s most unlikely partner was a remarkable Catholic priest, Father Scanlon, of Australian-Irish ancestry. He was a rotund little man with a shock of red hair. In the evenings while fellow monks posted themselves at strategic points as lookouts, Father Scanlon knelt beside the wall apparently engaged in evening prayers. When Japanese guards passed they observed him with his prayer book in hand chanting loudly in Latin.

Scanlon had managed to work a brick loose at the base of the wall and through this opening his contact, a Christian woman named Mrs. Kang, would with the help of her little boys slip him large quantities of eggs, which he would then conceal under his flowing, brown monk’s robes. In time, Scanlon and Wade became the chief egg supplier for the camp.

His operation flourished for months until one fateful evening, in the midst of his activities, a Japanese guard approached. Though warned by his lookouts of the pending danger, Scanlon was unable to get word to Mrs. Kang to halt the flow of eggs which she continued hurriedly shoving through the opening and under his robes.

In desperation, Scanlon commenced a loud recitation of his “prayers,” all the while calling his brothers in Latin. But too late. At this most inopportune time, the guard, in an unusually friendly mood, stopped to engage him in conversation. Still the eggs kept coming, until finally the sound of cracking shells and a tell-tale mess of yokes flowing out from beneath Scanlon’s robes gave him away.

With a shout of rage and wild gesticulations, the soldier hauled the monk off to the guard house.

When news of Scanlon’s arrest circulated, there was dark speculation about his fate. Would he be shot?

Possibly tortured?

When authorities declared, however, that the priest’s punishment for his crimes would be two weeks in solitary confinement, they were baffled by the smiles and muffled laughter their announcement provoked. They did not know as we did that Scanlon, a Trappist monk, had spent most of the past 25 years in a small cell under a vow of silence.

Though Scanlon was safely behind locked doors, the Japanese discovered they were not easily done with this pestilent fellow. At night he made it his custom to sing his Latin prayers in a booming voice. Guards, housed in a nearby building and trying to sleep, had little appreciation for this show of piety. Yet possessing the Asian’s typical superstition and awe of religious ritual, they were hesitant to forbid these clearly obligatory “holy exercises.” As a result, after one week’s incarceration Scanlon was released.

Escorted back to his quarters, he was followed by the Salvation Army marching band playing a spirited number!

Though for us internees the penalty for black- market activities was usually two weeks solitary confinement, an experience which I was destined to share, our heroic Chinese friends often helped at the risk of their very lives. One coolie trying to get goods to us atop the wall was electrocuted on the high voltage, barbed-wire fence. The Japanese authorities left his corpse hanging for days as a grim warning to all aspiring black marketeers. Others of our Chinese cohorts, more fortunate, were merely beaten up. Two, however, were taken outside the compound and within earshot executed by a firing squad. Another, found carrying contraband goods, was seized by the arms and legs, his body swung like a battering ram against the brick wall until his skull was a bloody pulp.

In 1944, the change in the chief officer in charge of the guards brought a crackdown which meant an end to our black market business. The motivation for this we soon learned, far from being any concern for maintaining the integrity of neither camp rules nor increased malice for the internee miscreants was simply greed. With the progression of the war and inflation, our captors, too, were finding themselves increasingly hard pressed for cash. In the black-market business they saw lucrative opportunity for personal advantage. Thus business continued as usual, but now the middlemen were our Japanese guards, who like syndicate bosses fought among themselves for choice customers and the larger share of the trade.

Before leaving the subject of food, let me quote a typical entry in my diary, this for October 26, 1943:

Before leaving the subject of food, let me quote a typical entry in my diary, this for October 26, 1943:

The 23rd was a great day — our day. I was trying all week to get two chickens as a surprise for Christine to celebrate our anniversary three years in China. It was only on Friday I was able to place the order with merchant Han. I got up early Saturday morning full of hope that the order would somehow get through. And yet, there was really little chance, for the Japs have been keeping close vigil.

I climbed up the drain, high enough to peer over the wall, and soon saw Han coming. The coast was clear. I told him to quickly come with the groceries. Soon they began to pile in — two chickens, two bottles of peanut oil, 250 eggs, 40 tins of strawberry jam, 30 pounds of sugar — a total of $1020 FRB (or U.S. $255). Business was just finished when the guard appeared. He had a strong suspicion we had been “dealing,” for a close watch was kept on Hilda’s room where the goods had quickly been stored.

Coming to our room proudly carrying the chickens, I found that Christine had gone to the hospital for Sandra’s breakfast. She had thoughtfully saved a chocolate bar from last summer and had left it as a gift — a real gift these days. A card on it read, “Welcome To China!

Happy 23rd Sweetheart.” I placed the chickens in a basin, transferred the card to the chickens’ feet and left with our food carrier to get our breakfast from the dining hall. Christine was happily surprised and they were a real treat. The first chicken in many months! We made chicken salad for a little party that evening and in addition had several meals of chicken, rice and gravy. (This was one of the rare occasions when we had received a small portion of rice from the canteen.)

Friday, I baked a small cake for the occasion. We had some walnuts issued to us and were able to make a chocolate icing which included chopped nuts! It was a delightful change. In the evening Hayes, Cotterrill, Ditmanson, Marjorie Monaghan, K. Porter, M. Scott came in and we enjoyed games and eats. A very full tea. (It was times like these which helped us keep our sanity and momentarily forget about the stress.)

Sunday was a full day. The 11 a.m. service was splendid. Dr. Howie, medical missionary of the CIM, spoke on Ezekiel 33: “Son of man I have appointed thee a watchman. If we fail to warn the wicked, their blood is required at our hands” — what a great responsibility. About 40 present. Went to prayer and open-air meeting at 3 p.m. At the 4:30 service in the church Dr. Martin spoke — not very inspiring to me.

We led the evening hymn-sing. Lights were out and few came. But by candle light we sang the favorites from memory. Christine and I sang, “Back of the Clouds.” (See words at end of chapter.) We used the double chorus “In My Heart There Rings a Melody” and “Sunshine and Rain.” We also used the hymn story of “It Is Well With My Soul.”

#

[further reading] ...

copy/paste this URL into your Internet browser:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/GordonHelsby/Helsby(WEB).pdf

#