by Joyce Bradbury, née Cooke

Chapter 5

[excerpts] ...

Everybody I knew worked hard for the benefit of the whole camp and I am not aware of any problems with persons not pulling their weight. There were four kitchens and dining rooms. Because of the food supply situation, it was a big job trying to satisfy the hunger of the inmates. Sadly, that was never really achieved. My father, a qualified accountant, was given cooking duties in a communal dining room where meals were cooked and served in relays. Mum also worked in the kitchen and made craft goods.

Everybody I knew worked hard for the benefit of the whole camp and I am not aware of any problems with persons not pulling their weight. There were four kitchens and dining rooms. Because of the food supply situation, it was a big job trying to satisfy the hunger of the inmates. Sadly, that was never really achieved. My father, a qualified accountant, was given cooking duties in a communal dining room where meals were cooked and served in relays. Mum also worked in the kitchen and made craft goods.

Our food was sparse and we were always hungry. It was usually boiled sorghum seeds for breakfast. Sorghum is usually grown in China for livestock feed. It is made up of little red seeds which are awful to eat but I have since been told they are a good source of protein, fibre and energy. They are difficult to swallow and I had to chew and chew them. My mother would say: “Keep chewing it until you can swallow it or you will go hungry.” Lunch would usually consist of one scoop of a thin vegetable stew. We were issued with a little tin plate and a tin cup. We had potatoes, carrots, leeks and Chinese turnips. The camp cooks were ingenious but the food was insufficient.

Sometimes there was enough for second helpings but not often. On these occasions, the extras would be served at half a scoop. Families often put their whole ration into a larger container to take back to their rooms to eat. Somewhat surprisingly, there was never any rice for us. I presume it all went to the Japanese military.

It was very difficult for the younger children. They had to go hungry and they did not understand what was going on. The rest of us just had to put up with the shortages. We were given some flour, which the inmates made into bread. The bread always tasted stale to me, although it was freshly made. We had peanut butter because Wei-Hsien grew a lot of peanuts. The peanuts were ground by hand either in the bakery or the kitchen and that’s what kept us going. I still like to eat peanut butter.

It was very difficult for the younger children. They had to go hungry and they did not understand what was going on. The rest of us just had to put up with the shortages. We were given some flour, which the inmates made into bread. The bread always tasted stale to me, although it was freshly made. We had peanut butter because Wei-Hsien grew a lot of peanuts. The peanuts were ground by hand either in the bakery or the kitchen and that’s what kept us going. I still like to eat peanut butter.

On one occasion a load of potatoes was delivered and dumped in a corner of the parade ground. The Japanese would not allow us to move the potatoes and they were left out in the weather until they started to rot. We were then told to eat them and when the inmates complained, the Japanese said: “You’ll get nothing else until the potatoes are eaten.” So, we ate them.

When a horse dropped dead behind the camp near the Japanese officers’ quarters, the Japanese refused to let the inmates eat it until it was maggoty and putrefying rapidly. They said, once again: “Eat it ― you’ll get nothing else until you do so.” The inmates promptly skinned the carcass and removed the rotten areas as much as possible and stewed the rest. We were rarely served meat.

Some inmates brought canned food with them into the camp but my family did not. One of our family’s good friends, a wealthy lady, brought a fairly large quantity of canned and preserved food into the camp and although she had been allocated work by the committee, she preferred to employ others to do her share on the payment of her food to them. Eventually, she ran out of supplies and then had to do her share of work. We kept in touch with her until she died several years ago. In her latter years she showed us a thick coil of malleable gold which could be worn around her wrist saying: “If ever I have to go into camp again, I will take this gold with me and cut off little bits to use to buy food.”

I do not remember any shop in the camp where we could buy necessities such as food or toiletries although I have since been told there was one for a short period of time. A cake of soap was issued now and again. We used that to do our laundry outdoors in large round tin wash tubs with two handles. We had to cart our laundry hot water in buckets from the shower block boiler.

Many people desperate for a smoke rolled used dry tea leaves into cigarettes and smoked them. My mother who was a heavy smoker did this, but after a lot of urging from my father she gave up smoking for the rest of the war.

While there was a shoe repair shop in operation, new shoes were non-existent and when my brother Eddie wore his shoes out, mum made a pair out of canvas for him. It took her days to sew them but he wore them to pieces within a couple of hours. Many of the children went barefoot. My mother was more successful at making cloth toys for children which she used to trade with other inmates for canned and preserved food.

[excerpts] ...

I lost weight but otherwise remained healthy except for tinea of my toes for which one of the doctors gave me Condy’s crystals which helped heal them. My brother went to the camp hospital and received treatment for a cut lip.

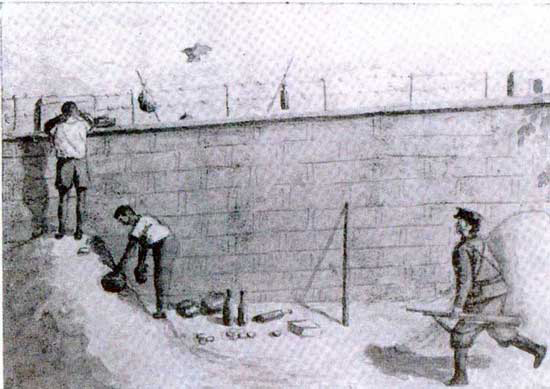

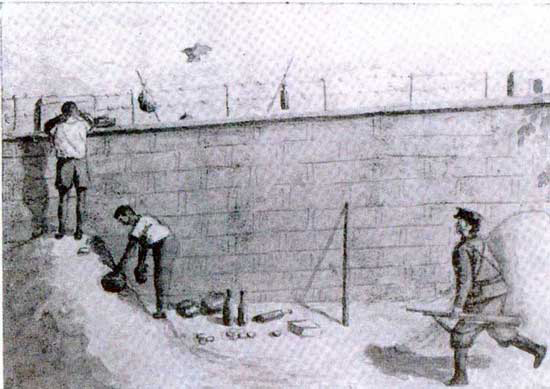

BLACK MARKET WALL (EAST) The building in the picture would be the morgue, and was also the place where the trappist monk, Father Scanlan, was confined after he was caught buying eggs in a “black market” operation. At the time of his confinement there was a funeral for a priest who had died of cancer, and I was assigned the task of sneaking down from the burial ground (the vantage point of the artist) to the small building and passing a flask of water to Father Scanlan. The feat was successfully accomplished.

During our imprisonment my brother was still recovering from tuberculosis. The doctors handled limited supplies of milk and eggs for babies and children under 10. Because Eddie turned 10 at Wei-Hsien, he did not qualify for the milk and eggs. This annoyed my father who thought he should receive milk and eggs to help him recover. Pop was working in the cookhouse one day wondering how he could get nourishing food for Eddie when a pigeon flew in through a window and fell into a vat of boiling soup. In no time it was plucked, cooked and fed to my brother. Pop always said the impromptu pigeon meal saved young Eddie’s life.

There was a black market in the camp. Chinese used to pass food through holes in the camp’s perimeter wall under cover of darkness and payment would be made in money or articles of jewellery. My wristlet watch went this way because my parents had no jewellery to barter.

Sometimes, the food was donated by Chinese friends of inmates.

Our room was near the perimeter wall and Pop made a hole in it by removing a brick. Pop used to act as a blackmarket buying agent for others. Mr de Zutter used to be his lookout and if he saw a guard coming he would warn Pop by saying: “Good night, I’m going to bed now,” or starting to whistle. On one occasion my father was buying the Chinese sorghum-based wine called bygar when he was almost caught by the Japanese. He ran and jumped into his bed fully clothed, leaving the wine bottles on the table where my mother found them next morning.

One of the internees, Father Patrick Scanlan became our best blackmarketer. He specialised in obtaining food for the other inmates ― which he did for no profit. Some of the food he bought from the local Chinese came into the camp in large quantities. Its arrival supplemented our sparse Japanese-supplied rations. Amazingly, he was able to get special food wanted for the hospital inmates.

Once Father Scanlan was kneeling at the hole in the wall doing his black-marketing business when a guard came up. Father Scanlan immediately took out his prayer book and told the guard he was reading his prayer book and praying. The guard didn’t believe him because he knew even Japanese couldn’t read in the dark. Father Scanlan said he didn’t need light to read because he knew all the pages by heart.

This did not convince the guard and Father Scanlan was locked up behind the Japanese officers’ quarters and sentenced to solitary detention for two weeks by the camp commandant. His solitary confinement would have come as a breeze for Father Scanlan because he had spent more than half his life living in a monastery. To upset his captors, Father Scanlan, in the first several days of his confinement, chanted his prayers in Latin at the top of his voice. He continued night and day telling the sleepless Japanese officers that it was his duty as a priest to daily recite his mandatory collection of prayers called the priest’s office. Catholic priests daily say their office, generally silently or quietly. The Japanese were too superstitious to stop him. After several days, when the Japanese could stand our blackmarketing priest’s sleep-disturbing prayer chanting no longer, they released Father Scanlan.

News of Father Scanlan’s release triggered one of the most joyous days in the camp. Everybody came out and cheered him. The Salvation Army members in the camp co-led by Father Scanlan’s fellow Australian, Salvation Army Major Henry Collishaw [31], assembled. They escorted Father Scanlan through the compound with their 20-piece band blaring away. It was a joyful occasion for us and for Father Scanlan. The Japanese guards were surprised by our reaction to Father Scanlan’s release. However, they took no punitive action. Without delay, Father Scanlan immediately resumed his blackmarketing.

Father Scanlan had a narrow escape on another occasion when he had about five dozen blackmarketed eggs hidden in his upper clothing. He was confronted by a guard. He immediately squatted on the ground and said in Chinese: “dootzetung, dootze-tung” which means sore tummy or diarrhoea. Because this was a common ailment, the Japanese soldier believed him.

People like Pop, Stan, and Father Scanlan helped keep us alive during these years and we were all very grateful to them. Most of the blackmarketed goods brought into the camp consisted of eggs, vegetables and sugar.

Occasionally, the Chinese smuggling goods to the camp were caught and they were given a severe beating by the Japanese. There were suggestions in the camp that two Chinese were shot for smuggling.

[excerpts]

Some Red Cross parcels were received at the camp. The arrival of the first lot led to bad blood because some Americans claimed they should solely have them because they came from the American Red Cross. When a second lot of Red Cross parcels arrived, the question of their distribution was solved after discussions the camp management committee had with the Japanese camp commandant. The Japanese ordered the parcels to be fairly shared or they would be with-drawn. Incidentally, the Red Cross parcels received at the camp over the internment years came from the Australian Red Cross and the American Red Cross. The Australian Red Cross parcels were arranged by a Sydney relation of the interned Tipper family from Australia.

In the Red Cross parcels were chocolates, canned and packet food and knitting needles with wool. There was some clothing too. I will never forget the candy-coated Chiclets chewing gum that I received as my gift in the American Red Cross parcel sharing. After chewing it all day, I stuck it each night on the side of the cupboard near my bed and placed it in my mouth the next day. I did that until the chewing gum disintegrated. I also received a frock which came in one of the parcels. It was a winter dress of woollen material and I still have a photograph of myself wearing it after the war. Towards the latter stages of the war the Red Cross parcels stopped coming.

One of the perks of working in the food areas was taking home extra food. My father was able to bring home dripping once in a while which we ate on our bread. We were always hungry and fantasised about food. Some people thought about milk and sugar because we had to drink tea without milk or sugar. The tea was ladled out to us from large pots. My mother missed her coffee and we all missed bacon and eggs. I do not remember anyone putting on weight. Some inmates were caught by other inmates stealing vegetables, bread and other food.

They appeared before a camp committee which decided whether they were guilty or not. I don’t remember what punishments were inflicted except the names of the guilty were put on the notice board.

It is possible some of the priests, particularly the Trappist Father Scanlan and the Belgian Father Raymond De Jaegher, who was a seminary professor, actually ate better in the camp than they did before imprisonment because pre-camp they lived mainly on bread and water. Father Scanlan often said that. I was never quite sure whether he and the other priests were trying to bolster our spirits. I knew that Trappists were required to live under severe rules of austerity and silence and Father Scanlan writes in his book that meals in the monasteries were always spartan.

[excerpts] ...

#

[further reading] ...

BLACK MARKET WALL (EAST) The building in the picture would be the morgue, and was also the place where the trappist monk, Father Scanlan, was confined after he was caught buying eggs in a “black market” operation. At the time of his confinement there was a funeral for a priest who had died of cancer, and I was assigned the task of sneaking down from the burial ground (the vantage point of the artist) to the small building and passing a flask of water to Father Scanlan. The feat was successfully accomplished.

copy/paste this URL into your Internet browser:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/ForgivenForgotten/Book/ch5.htm

#