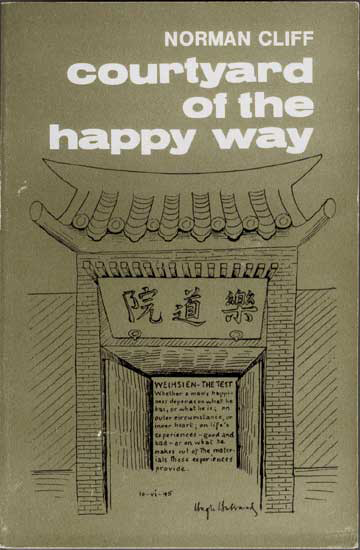

- by Norman Cliff

[excerpts] ...

[...]

[...]

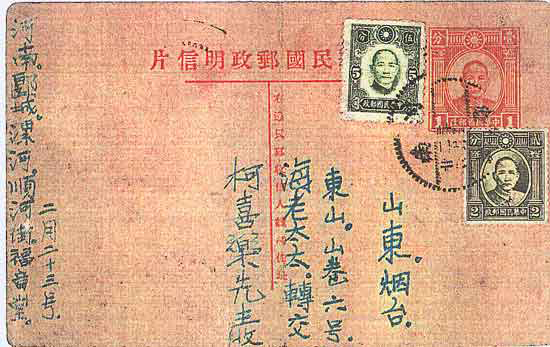

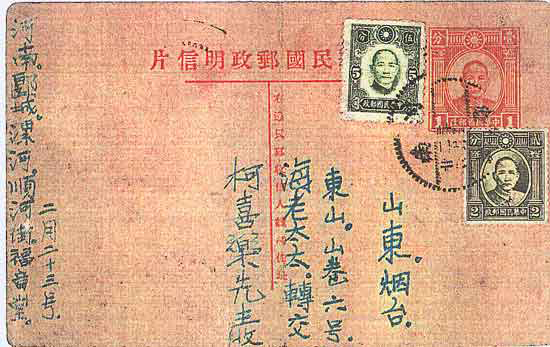

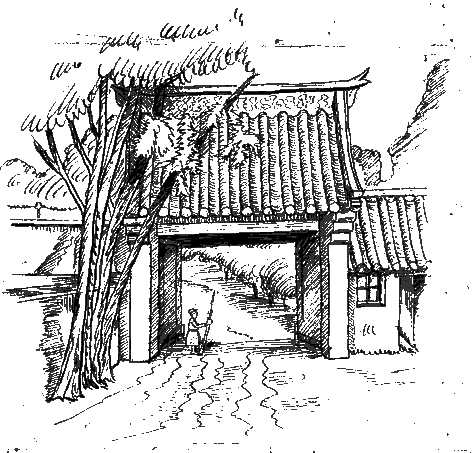

One day I was on one of my routine visits to the guards when, just at the gate, I saw a Chinese postman furtively dropping some mail in the watchman’s house. The watchman beckoned to me. They were Chinese-style envelopes with printed red lines surrounding the names and addresses of the addressees. I looked carefully at the Chinese characters—they were letters addressed to various members of the staff.

I de- livered them excitedly to Mr. Welch. Inside were letters in Chinese written on thin rice paper. We identified the names of the children for whom they were intended. I helped to translate them. Boys took them excitedly to the other members of their families at the Girls and Prep. Schools.

Replies written in Chinese and placed in Chinese envelopes were promptly posted back to parents in inland unoccupied China. We had outwitted the Japanese, for how could they identify as enemy correspondence letters written in Chinese to parents, using their Chinese names?

Soon the postman was coming once a week with small batches of letters. I would collect the mail, identify the names and distribute the letters.

Soon the postman was coming once a week with small batches of letters. I would collect the mail, identify the names and distribute the letters.

Mail was now going back and forth at fairly regular intervals.

We then tried writing in English and posting the letters inside Chinese envelopes. If this were successful, correspondence with our parents would be so much simpler.

And successful it was.

The batch of mail brought by the sympathetic Chinese postman was getting larger and larger. I never heard of any instance when mail of this kind was intercepted.

Through this same route came our Oxford School Leaving Certificate examination results.

Through this same route came our Oxford School Leaving Certificate examination results.

They had gone from Oxford to our Mission headquarters in Chungking, Free China, and then to us at Weihsien in a Chinese-style envelope. The results were outstanding. The “best school East of Suez” was certainly maintaining its good reputation for academic successes.

[excerpts]

A German Jewish dentist was allowed to come at regular intervals to attend to our teeth in a room close to where the Japanese guards lived. While extracting teeth, inserting fillings and so on, he spoke in French and German, passing on the news he had heard over the radio at his home.

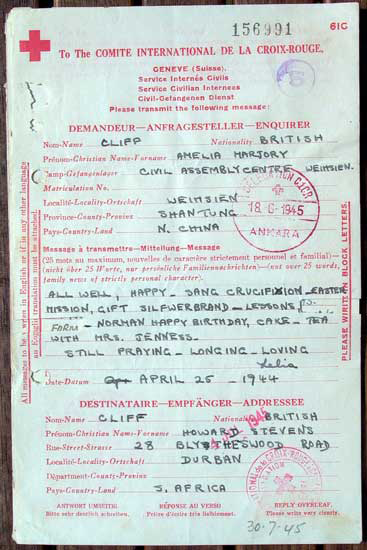

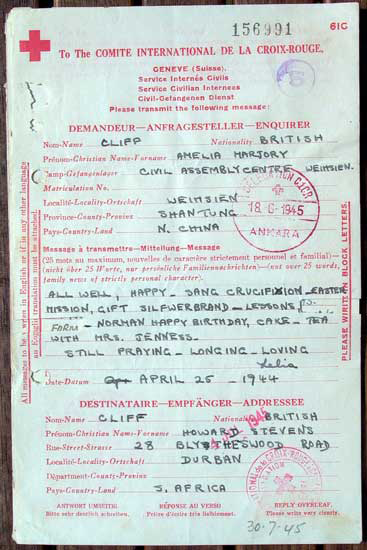

It was just at this time that Mr. Egger of the Swiss Red Cross made his first appearance with Red Cross letters and messages from the Mission leaders, as well as news of the other camps in Hong Kong and Shanghai. As he was based at Tsingtao, we were to see him at regular intervals throughout our internment period.

[excerpts]

CHRISTMAS 1944 was now upon us. News from parents had for most families become sparse and spasmodic.

Periodically during 1944 we had been given Red Cross letter forms to complete. With the issuing of these was a long list of prohibited matter, the weather, camp activities, food and so on. The Japanese during the years following Pearl Harbor had become wise to the deeper meanings behind such messages as “Awaiting Uncle Sam’s arrival”, “John Bull urgently needed”, “All is well. Tell it to the marines.”

The maximum length of the communication was twenty-five words, and the contents had to be straightforward with no double meanings.

As we sat in front of those official forms struggling to decide what we could write without infringing any of the regulations framed about their wording, many of us decided that the only thing that mattered was that our parents should receive a piece of paper on which was our handwriting; the contents were immaterial. Just to receive that form meant that we were alive, however little it gave of personal news, so we took every opportunity to complete them. Later we were to learn that the Japanese censorship in the guardroom could not keep pace with hundreds of internees writing letters, and therefore proportionately few reached their destinations.

The maximum length of the communication was twenty-five words, and the contents had to be straightforward with no double meanings.

As we sat in front of those official forms struggling to decide what we could write without infringing any of the regulations framed about their wording, many of us decided that the only thing that mattered was that our parents should receive a piece of paper on which was our handwriting; the contents were immaterial. Just to receive that form meant that we were alive, however little it gave of personal news, so we took every opportunity to complete them. Later we were to learn that the Japanese censorship in the guardroom could not keep pace with hundreds of internees writing letters, and therefore proportionately few reached their destinations.

[further reading] ...

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/escape/Letters/escapeLetters.htm

and

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/Books/Courtyard/eDocPrintPro-BOOK-Courtyard-01-WEB-(pages).pdf

#