- by Pamela Masters, née Simmons

[excerpts] ...

[...]

[...]

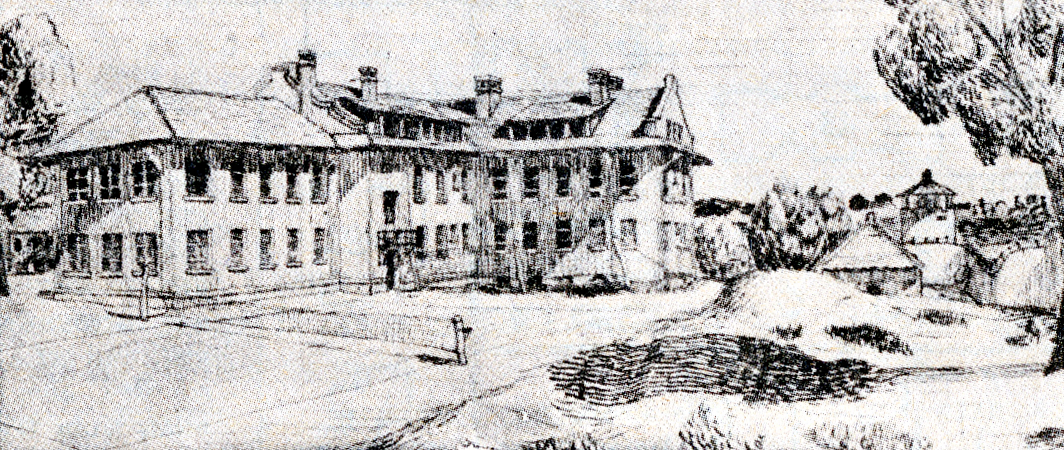

Breakfast the next day in the steamy community kitchen was skimpy and pretty foul: weak Chinese tea and bread porridge. The latter made with sour bread that had been soaked in boiling water and stirred to a mush, as it was too stale to serve any other way. With no sugar or cream to add to it, it was almost inedible. While we were eating, a committee member came in and told us that, when we were through, we were to go to the athletic field for indoctrination, housing, and work assignments.

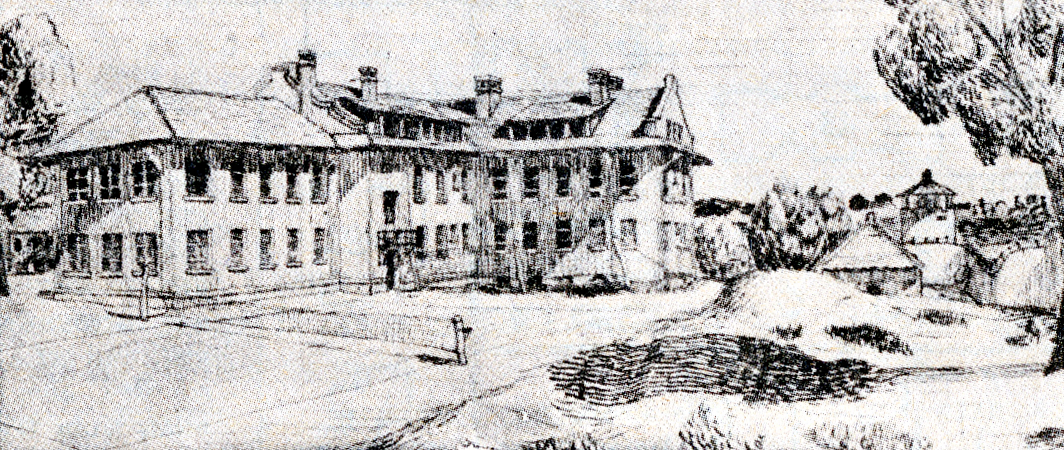

The field wasn’t hard to find as it was the only large, treeless area in the camp, and through the years, it was to become the site of most of our outdoor group activities and daily headcounts.

[excerpts] ...

Before we left the roll-call field, all the single men and women were told to report to the respective dormitory areas, and heads of each household to the administrative office compound to be assigned cell numbers—only they called them room numbers. Meanwhile, most of the committee responsible for our orderly move to camp pitched in once more to organize work details.

All those not preparing food were to be assigned to cleaning up the camp. The rains of the day before, which had gone on through most of the night, had left the main roadway a quagmire. I found that the stench that had greeted us on our arrival was from overflowing latrines, augmented by piles of soggy garbage in various phases of decomposition.

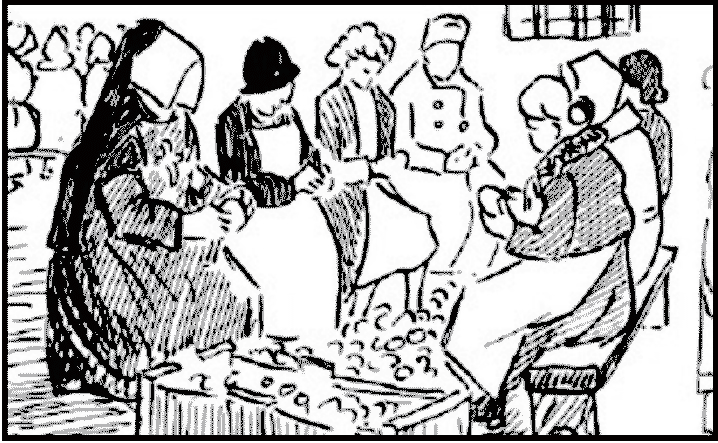

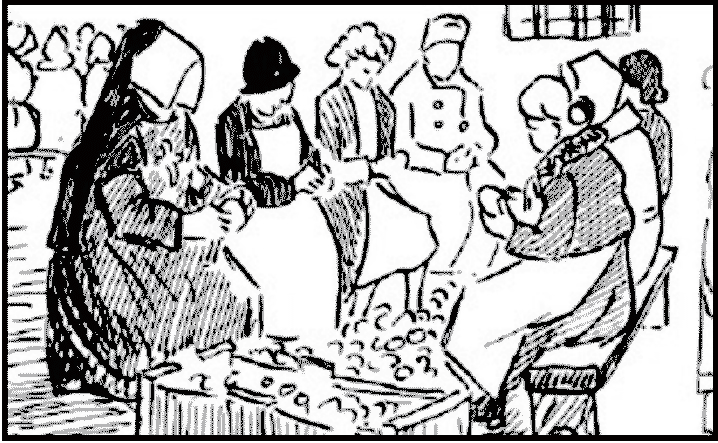

Somehow I missed the cleanup detail and found myself peeling potatoes with twenty others in the community kitchen—dubbed “Number 2 Kitchen” or “K-2”—where we’d had breakfast a couple of hours earlier. With so many people, and so few potatoes, the job was soon done, and I left the kitchen compound and stepped out onto Main Street, the name some enterprising individual had already posted on the road leading up from the main gates.

[excerpts] ...

[excerpts] ...

I learned later that they told the assignment committee they felt they could help the camp more if they were allowed to do the Lord’s work, and then asked if they could call a prayer meeting in the church.

They were advised they would have to get in line if they wanted to use the assembly hall, as there were denominations ahead of them that had prior rights.

[excerpts] ...

Margo had befriended several other war brides whose husbands were in military camps, and they helped each other out. She also volunteered to work in the hospital as a nurse’s aide and had started pretty rigorous training. She admitted one evening that it was nothing she planned to do for the rest of her life, but it was a change from secretarial work and a great way to help others.

I was restless. Everyone seemed to be finding their niche except me, and although I was getting used to the routine, I was definitely not enjoying it.

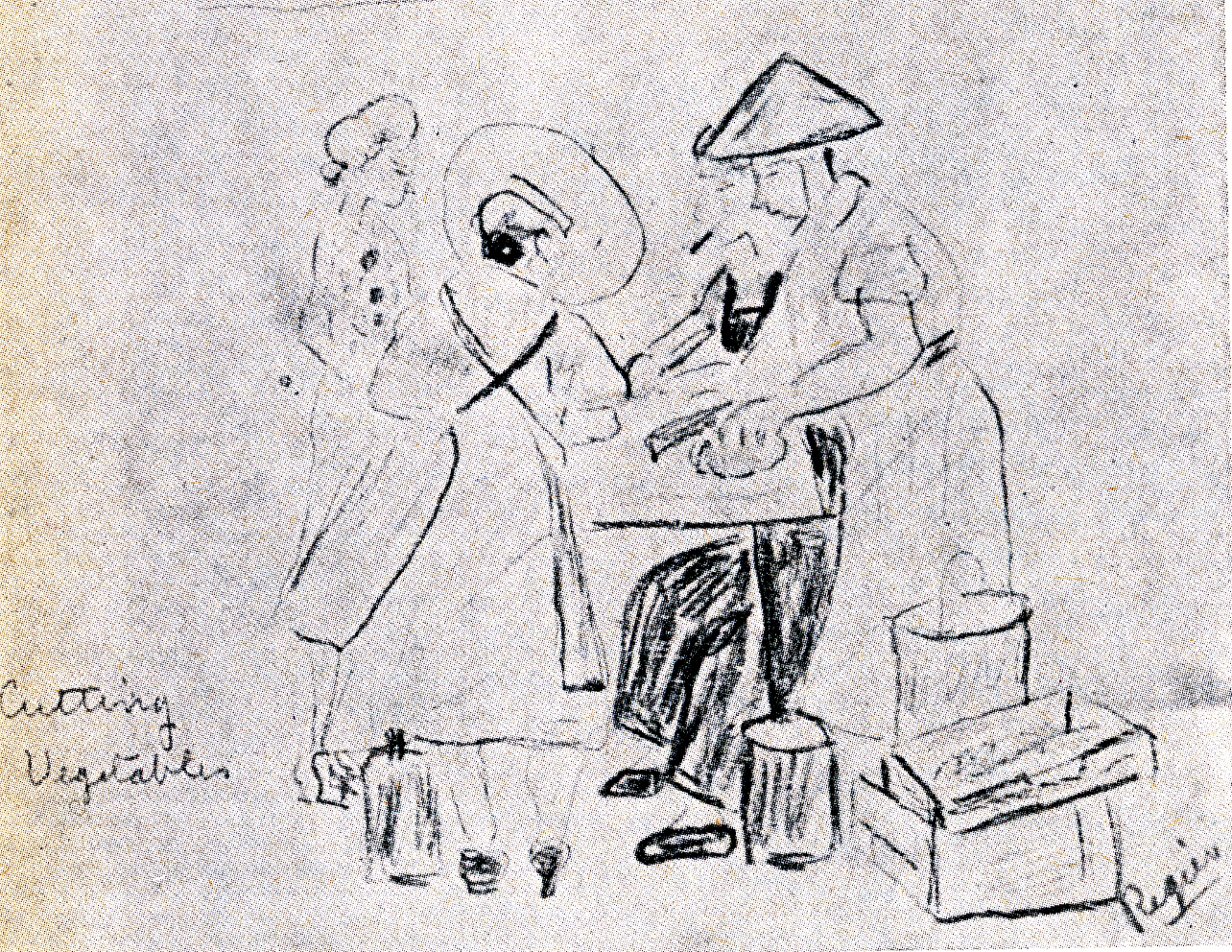

My idea of nothing was peeling potatoes, or chopping leeks for a couple of hours a day, then tramping around the camp looking for something to do. After a couple of weeks, I complained to the assignment committee, but was told everything would change soon, as they were planning to open school for us in Number 2 Kitchen, and we would be too busy studying to have time for any other work.

I didn’t know which would be worse, chopping leeks or trying to study in a busy kitchen. I found out soon enough when classes started, and I tried to apply myself with tears running down my cheeks from the fumes of the vegetable prep area.

[excerpts] ...

Surprisingly, as we headed for the library, my dark thoughts were replaced by memories of the camp’s second “minor miracle”—the arrival of several cartloads of books during the sweltering heat of the previous summer.

When they were uncrated, most were found to be in deplorable condition, and the assignment committee requested that if anyone knew anything about bookbinding would they please step forward. Dad, who had had a fine collection of books, some rare first editions, had taken up binding as a hobby in the port, but had never done much with it. He told the committee he would gladly do the job.

His workshop was a partially isolated little cell near the hospital area. And that was just as well, as the fish glue he heated up to tip in the pages and mend the spines had a stench that made me gag. I once asked him how he could stand it, and he said, “Oh, like everything, you get used to it.”

I had to admit he did a lovely job on the books; especially the spines that always got the worst beating. He not only repaired them so that they were stronger than before, but would painstakingly letter the titles and authors, so that they looked like the original bindery job. You could tell he was happy in his work. And, as he was also his own boss, I knew he read most of the books before, or after, he bound them. Dad, like me, loved to read, only he had a photographic memory. He could scan pages so fast it was impossible to believe he had read them. He used to read a book a day on tiffin break in Chinwangtao. He not only read the books, he devoured them; and from them he got a vocabulary that was second to none. I never recall opening a dictionary until I went away to the convent; if I got stumped, I always asked him for the meaning of a word. He would not only give it to me, but he would give me the root, the usage, and all the derivatives. He was my dictionary.

Oh, hell, Dad, how can you be so nice and such a dirty bounder at the same time?

[excerpts] ...

[excerpts] ...

Margo wasn’t to be soothed: her nostrils flared and her eyes flashed. “You bet I’m tired! I’m tired of helping them pump his stomach to save his life. Dammit, it’s not fair! Like that witch who ate a box of match heads and got violently ill. We worked around the clock on her. And the one who slashed her wrists, but not deep enough to make it work. Or the umpteen Italians, begging for attention and a way out of their prison compound, who never hang themselves high enough to get anything more than a crick in the neck and a week in the hospital! They don’t mean to commit suicide; all they want is sympathy, and I’m fed up! They don’t deserve it. I’m going to talk to Roger Barton. I think, if they care so damned little for their lives, we should make them into a suicide squad, and if we’re attacked, we’ll send them out as the first wave!”

I’d never heard Margo so hot on anything before, but then, I hadn’t worked upstairs with her in the sadly wanting hospital and seen all the suffering. When Ursula and I finally got her calmed down, I sensed she wanted to be alone, so after Alex picked up Ursula for their bridge game with Claire and Randy, I went for a walk.

[excerpts] ...

After Nico’s death, Guy asked for a change in jobs, not being able to face the bakery shift without his buddy. His first short stint was as a stoker in K-1, then he got transferred to the hospital diet kitchen where I worked. His shift followed Dan’s, so now I had two stokers I could look forward to working with, and most of all, it gave me a chance to talk with him without feeling shy and awkward.

Guy wasn’t as helpful as Dan, but he would pitch in and help if I asked him.

One morning, after getting him to help me wrestle with the blending of the soaked millet and boiling water, he stood back and watched while I stirred the mush with the long wooden paddle I used. Feeling his eyes boring into my back, I turned and looked at him, and some of my old animosity started to rear its ugly head, but I stopped when I saw his face. He looked tired, almost ill. “What’s up, you look dreadful,” I asked.

[...]

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/MushroomYears/Masters(pages).pdf

#