- by John Hoyte

[excerpts] ...

[...]

Fortunately for us, an earlier band of prisoners from Beijing and Tientsin had worked on improving matters, cleaning out the toilets (which were inches thick in human waste), and establishing two working kitchens.

Fortunately for us, an earlier band of prisoners from Beijing and Tientsin had worked on improving matters, cleaning out the toilets (which were inches thick in human waste), and establishing two working kitchens.

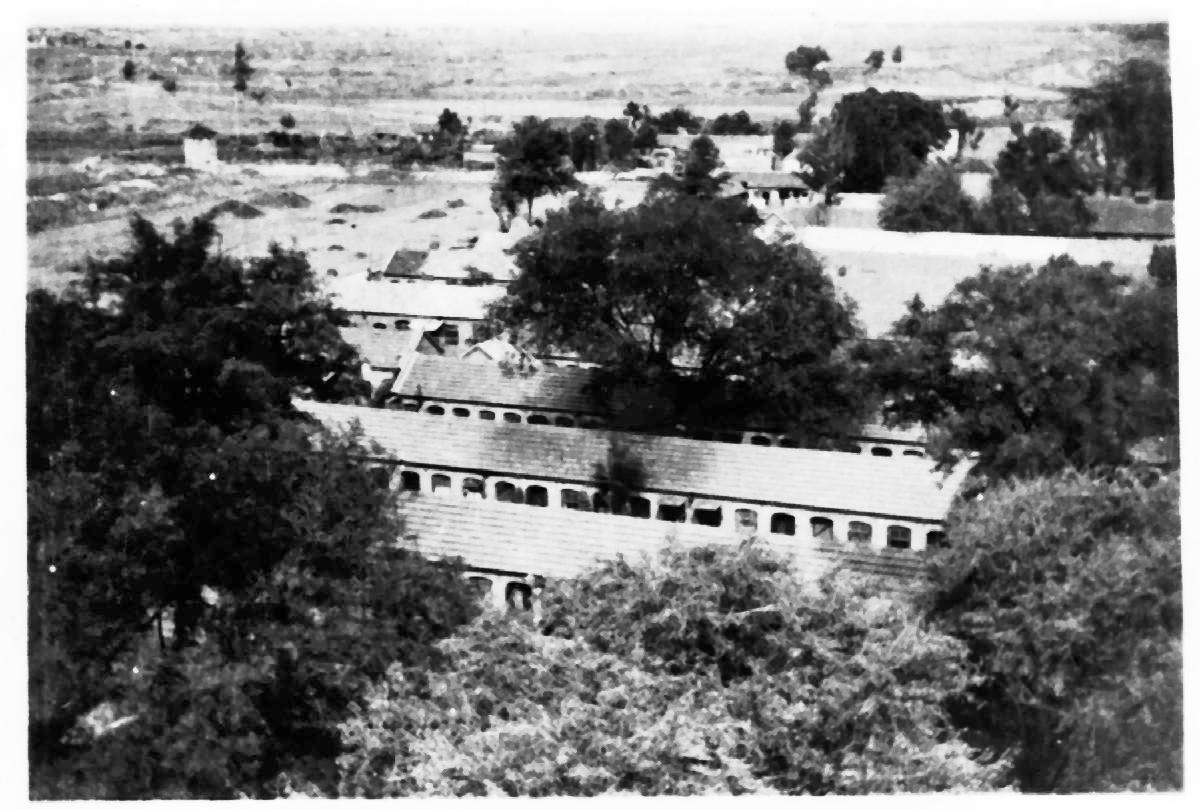

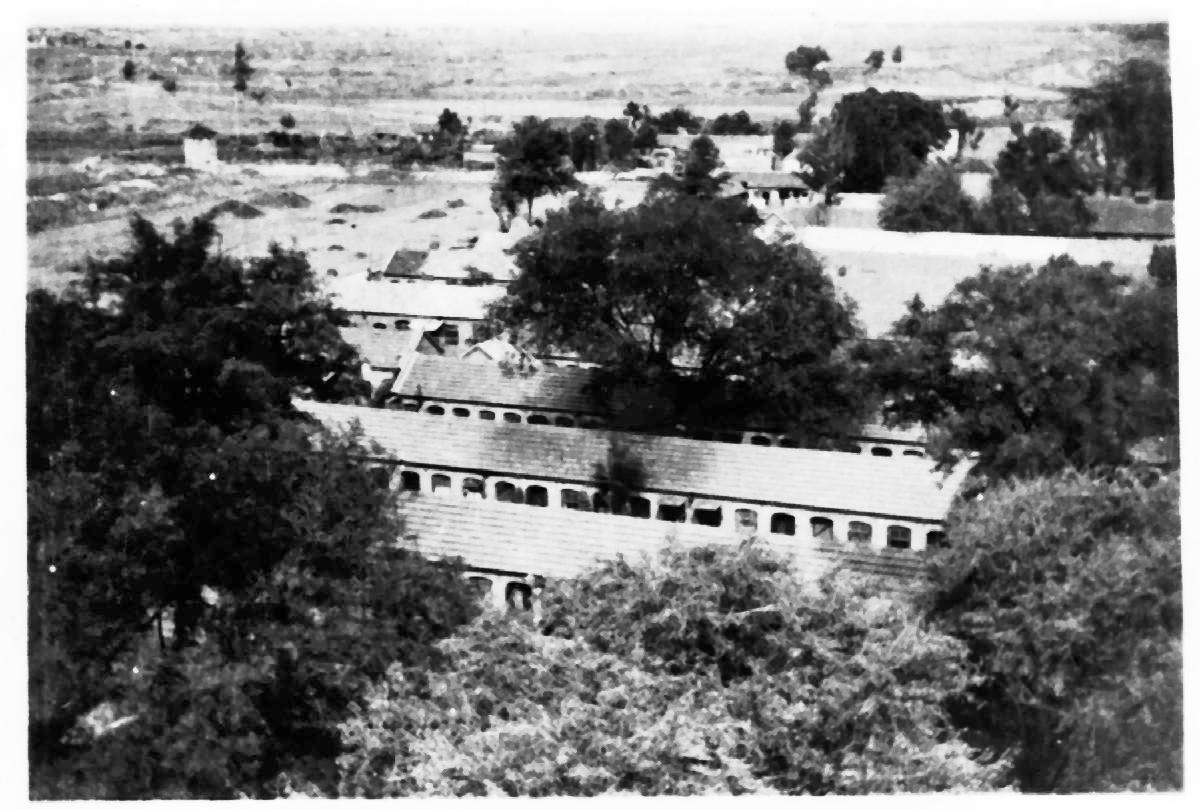

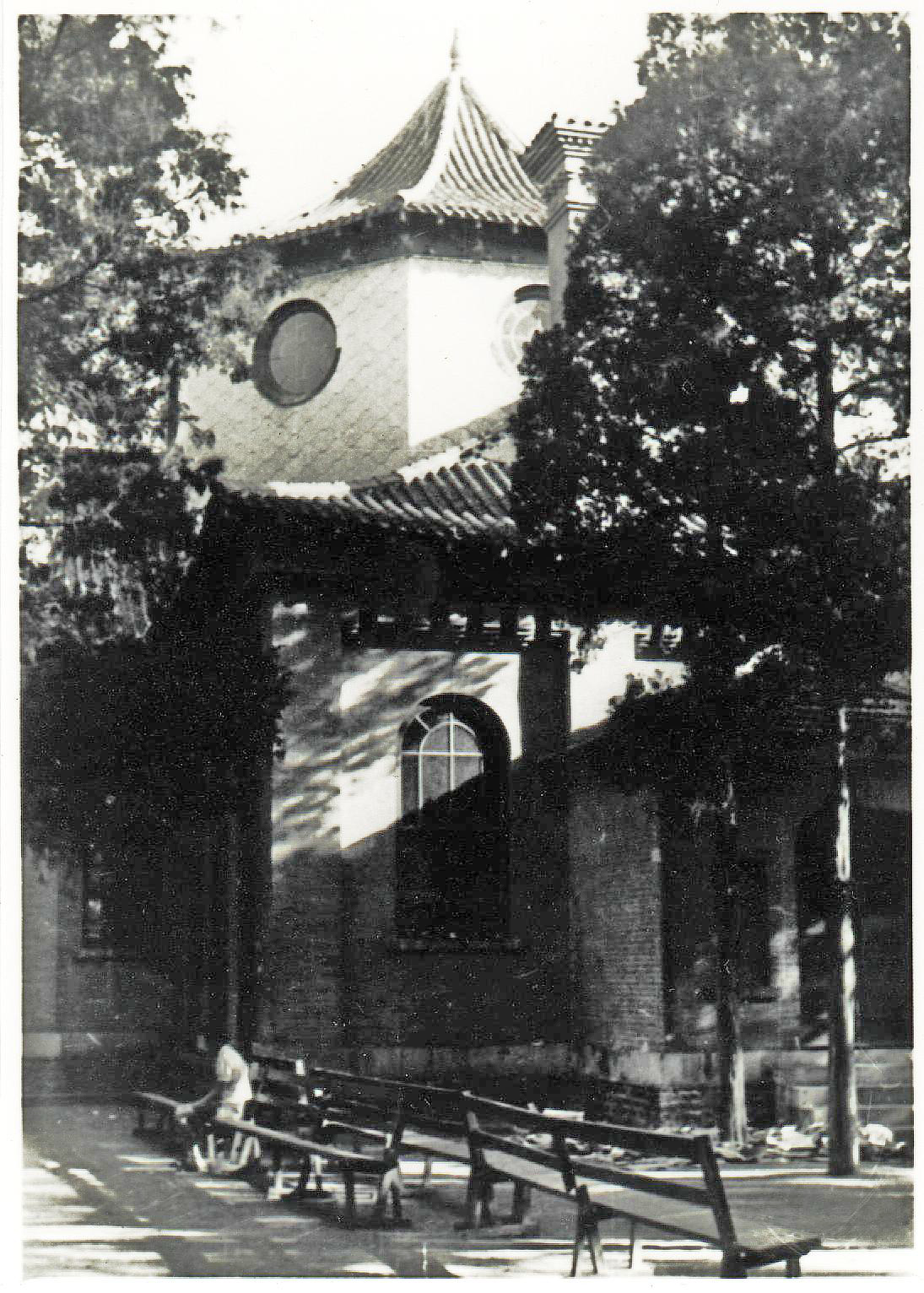

Our new home was about two hundred by a hundred fifty yards, and housed up to two thousand prisoners at its maximum.

There were rows and rows of tiny rooms which had been designated for Chinese students, each with a narrow door and window at the front and a small window at the rear, but now were crammed with prisoner families. With no running water or heat, the new inmates had to become very adaptable.

Six months earlier, the first batch had been brought in, followed by group after group of enemy nationals, as the Japanese called us, from many parts of northern China.

Before our three hundred arrived, there were about sixteen hundred prisoners. It was a crowd of many nationalities, the very last arrivals being Italians brought in after their country’s capitulation.

Together, they all formed a mixed bag of personalities, rich and poor, missionary and secular, young and old, generous and miserly, healthy and sick. Mr. Watham, for example, was a millionaire, the president of a huge coal mining operation, while Barbey was a drug addict picked up off the streets of Beijing. We all had to learn to live within the same primitive conditions.

[excerpts]

[excerpts]

JOBS AND WATER

Everyone had a job — even the slackers, and there always were some, who tried their best to get away with as little work as possible.

We kids watched the adults laboring away in the kitchens and janitorial services, making shelving and stovepipes, and providing many other services, and wondered how we could contribute. Eventually, we were given our own jobs.

Mine, as an eleven-year-old, was to work the manual water pump for an hour at a time. All the water for the camp was pumped up by hand from two deep wells into two thirty-foot water towers. Fortunately we never ran out of water.

Our pump was a long-levered, double-handled type, made of cast iron and creaking loudly as we operators moved the handles up and down.

For a whole hour we would work at it, with short breaks or taking it in turns.

The book lovers would be able to place a book beside the mechanism and read it while pumping. I tried to read The Scarlet Pimpernel this way. It worked for a while but my eyes would get tired refocusing all the time.

We climbed up the metal ladder fastened to the side of the water tower and gaze longingly at the cool liquid glory up there, in the sweltering heat of summer. Oh for a dip! This was, of course, strictly forbidden. I cannot remember the punishment but it must have been severe as not once did our little gang of eleven-and-twelve-yearolds go in.

The wells were contaminated with giardia, so all drinking water had to be boiled.

On long, hot summer days we would drink and drink and drink, mainly from old wine bottles, though the water was always lukewarm.

All the refrigerators that were in the compound had been taken by the Japanese.

My ten-year-old sister, Elizabeth, had the job of hanging out laundry to dry. During the summer this was fine, but in the bitter cold winters, her fingers turned black and blue. It was particularly painful gathering in the sheets that turned into solid expanses of ice on the clotheslines.

Cleanliness was a constant challenge, as soap was desperately short in supply. We were supposed to receive one small bar per person per month, but delivery was unreliable, the quality of soap was bad, and it had to cover all laundry personal toilet, and cleaning facilities.

Eventually whites took on a permanent grayness. After a few months, linens, socks, and other clothing became worn and torn, making repairing them a major project for the women and girls.

I was quite expert at darning my own socks, a practice I had learned from my mother.

Everything was recycled. Everything was hand-me-down. We were growing out of the clothes we had at the beginning of the war.

I became well acquainted with my brothers’ things. Leather was scarce and shoes precious. We went barefoot as much of the year as possible, definitely all summer and as much of the spring and fall as we could.

The camp shoe repair shop was much appreciated when leather started to fall apart.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/JohnHoyte/JHoyte(web).pdf

#