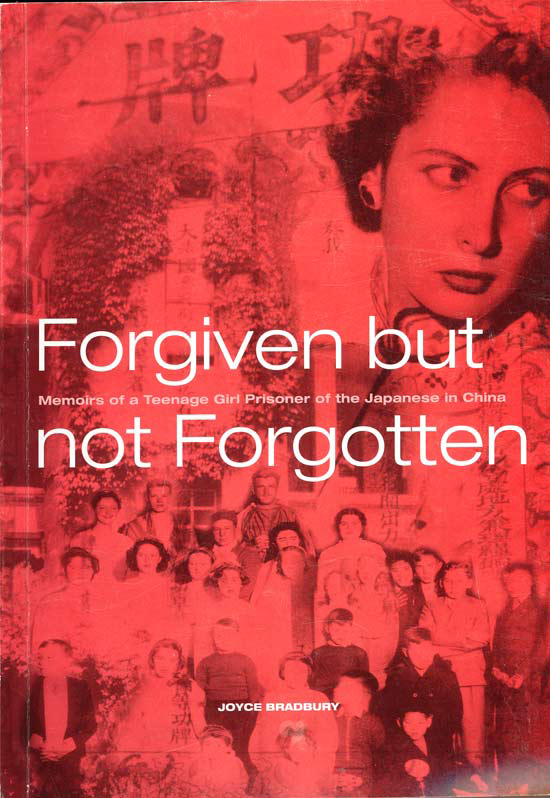

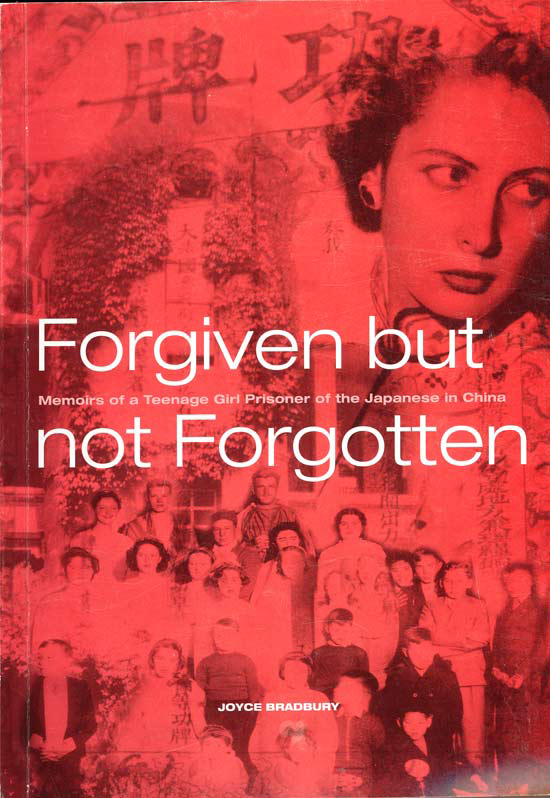

- by Joyce Bradbury, née Cooke

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

During the hotel internment, I was one of a group of children who put on a Christmas concert for internees. The girls dressed as angels.

During the hotel internment, I was one of a group of children who put on a Christmas concert for internees. The girls dressed as angels.

[excerpt]

No clothing was issued by the Japanese during the next three-and-a-half years. As children grew out of clothing, it was swapped at the exchange stall set up especially, which we called the White Elephant Exchange.

[excerpt]

The age range of the internees was wide. The oldest internees in mid-1944 were a missionary couple both aged 86. The youngest internee was a one-month-old infant. Because so many schoolchildren had been brought to the camp, there was a disproportionate number of children at the time the list was compiled.

[excerpt]

It was very difficult for the younger children.

They had to go hungry and they did not understand what was going on. The rest of us just had to put up with the shortages. We were given some flour, which the inmates made into bread.

The bread always tasted stale to me, although it was freshly made. We had peanut butter because Wei-Hsien grew a lot of peanuts. The peanuts were ground by hand either in the bakery or the kitchen and that’s what kept us going. I still like to eat peanut butter.

On one occasion a load of potatoes was delivered and dumped in a corner of the parade ground. The Japanese would not allow us to move the potatoes and they were left out in the weather until they started to rot. We were then told to eat them and when the inmates complained, the Japanese said: “You’ll get nothing else until the potatoes are eaten.” So, we ate them.

[excerpt]

While there was a shoe repair shop in operation, new shoes were non-existent and when my brother Eddie wore his shoes out, Mum made a pair out of canvas for him. It took her days to sew them but he wore them to pieces within a couple of hours. Many of the children went barefoot. My mother was more successful at making cloth toys for children which she used to trade with other inmates for canned and preserved food.

[excerpt]

I attended school in the camp. It was conducted by nuns, priests and staff from the Peking American High School. Most of the teachers were university trained. My father used to say to us: “You are getting the best education because these people are some of the most highly trained teachers in the world.” Text books were scarce and we had to share them. We had pencils and paper and some had fountain pens. We were given homework most nights.

[excerpt]

Other schools operated in the camp. This was done to help children who had been educated together before the war to remain together in school at the camp. The Chefoo School, which the Reverend Norman Cliff and his siblings attended as students, operated in the camp. The school was well organised with sporting teams and a Boy Scout group.

As soon as I turned 14 in mid-1942, I was given the regular job of cleaning toilets. I was given a bucket, a brush, some cloth and disinfectant. Every day I had to clean the ladies’ and gents’ toilets near the communal showers. There were no sewer or flushing toilets.

[excerpt]

During our imprisonment my brother was still recovering from tuberculosis. The doctors handled limited supplies of milk and eggs for babies and children under 10. Because Eddie turned 10 at Wei-Hsien, he did not qualify for the milk and eggs. This annoyed my father who thought he should receive milk and eggs to help him recover. Pop was working in the cookhouse one day wondering how he could get nourishing food for Eddie when a pigeon flew in through a window and fell into a vat of boiling soup. In no time it was plucked, cooked and fed to my brother. Pop always said the impromptu pigeon meal saved young Eddie’s life.

[excerpt]

The Salvation Army members were well keeping up people’s spirits. They constantly organised activities for younger children, visited the ill and encouraged people interested in learning to play a musical instrument. Reverend Norman Cliff, then a schoolboy, learned how to play the trombone from them and used to perform at their recitals.

There was also a Dutch married couple known as the `holy rollers’ because of their religious beliefs. They were members of a group of religious people who manifest their religious fervour by rolling on the floor while saying their prayers. They did their praying regularly because I used to see them from where we lived.

[excerpt]

The Japanese sergeant who was responsible for our section of the camp was known to us as Sergeant Bushing-de because he always said no to any question and “bushing-de” in Chinese means “no can do”. We used to refer to another guard as slippery Sam because he was sly and slippery in his actions towards us. There was also a big guard nicknamed King Kong.

Captain Yumaeda, who was one of the camp’s commandants, owned a nanny goat from which he used to obtain milk for himself and perhaps other officers. One day the goat wandered into the general camp compound and was immediately milked by the inmates until there was no more milk. My mother had a go at it but without success. Somehow or other we had some of the milk in our tea that day but I don’t remember how we got it. It was lovely. The goat never escaped again. The scene of all these ladies chasing the goat to milk it was a sight I will always remember.

Funny yes, but pathetic in retrospect.

[excerpt]

The clergy also worked. They performed kitchen duties, stoked hot water boilers for the showers and pumped water which had to be done 24 hours a day. They also helped with heavy work such as lifting when required. One Catholic priest, Father Schneider, was formerly a shoemaker and he was put in charge of the shoe repair shop. Some of the nuns worked in the kitchen, cleaning vegetables, and also taught in the schools alongside Protestant missionaries. Some nuns nursed and some volunteered for the terrible job of clearing overflowing toilets, which they did with grace and dignity.

The nuns wore veils over a stiff cloth frame called a “coif” on their heads when they first arrived. After a while, they dispensed with the coifs and just wore a veil pinned to their hair.

Many of the Protestant clergy had added tasks.

They had to tend to the needs of their families, of which there were quite a few.

[excerpt]

I attended school in the camp. It was conducted by nuns, priests and staff from the Peking American High School. Most of the teachers were university trained. My father used to say to us: “You are getting the best education because these people are some of the most highly trained teachers in the world.”

Text books were scarce and we had to share them. We had pencils and paper and some had fountain pens. We were given homework most nights.

On completing school in the camp at the age of 17, I was presented with a graduation certificate signed by Alice Moore, my camp school’s principal. Before her imprisonment, Miss Moore was principal of the Peking American High School. Amazingly, Miss Moore brought the blank graduation certificates with her and other necessities such as books for running a school in the camp. I still have the graduation certificate which says I graduated from the Peking American High School. I separately studied shorthand while I was attending high school in the camp. I still have my certificate of competency at a rate of 60 words per minute.

[excerpt]

We all lived together and helped each other. Nobody thought it strange for different religions to mix together in church. After all, we mixed together in everyday life in the camp so it was natural to mix together at worship. The church and the dining room were used for school rooms during the day but we had to vacate the dining room for lunch to be served.

[excerpt]

I had boyfriends for a while and then they either got sick of me or I got sick of them. There were plenty of young men there but I used to select those who were interesting and had personality. I don’t remember how many boyfriends I had those days but I don’t think I really loved any. I found it was good to be with someone who cared and was willing to sit and talk. There were no drugs that I am aware of and alcohol was a no-no for teenage girls. Everybody warned us what happened to girls who drank alcohol.

And sex was just not a thing we thought about. That was our training and upbringing ― especially for convent-educated girls.

[excerpt]

I did not leave the camp for short excursions into the local neighbourhood after the liberation.

To my mind, there was nothing to see. Just miles and miles of open fields and farms devoted mainly to cropping. For the younger children, schooling continued. Because I had finished high school I still had to do my camp committee- appointed chores. However, there was a big difference ― a difference in morale among us. We had music all day and we could have hot showers whenever we wanted them. And we could move around freely and visit friends at night. Above all, there was plenty of food. The American food parcels were brought in regularly. Fresh vegetables came in from the Chinese.

For reasons I have never fathomed, we still didn’t get any rice.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/ForgivenForgotten/p_FrontCover.htm

#