- by David Michell

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

It was late August 1944. I was eleven, one boy in a whole school of missionaries’ children interned under the Japanese.

It was late August 1944. I was eleven, one boy in a whole school of missionaries’ children interned under the Japanese.

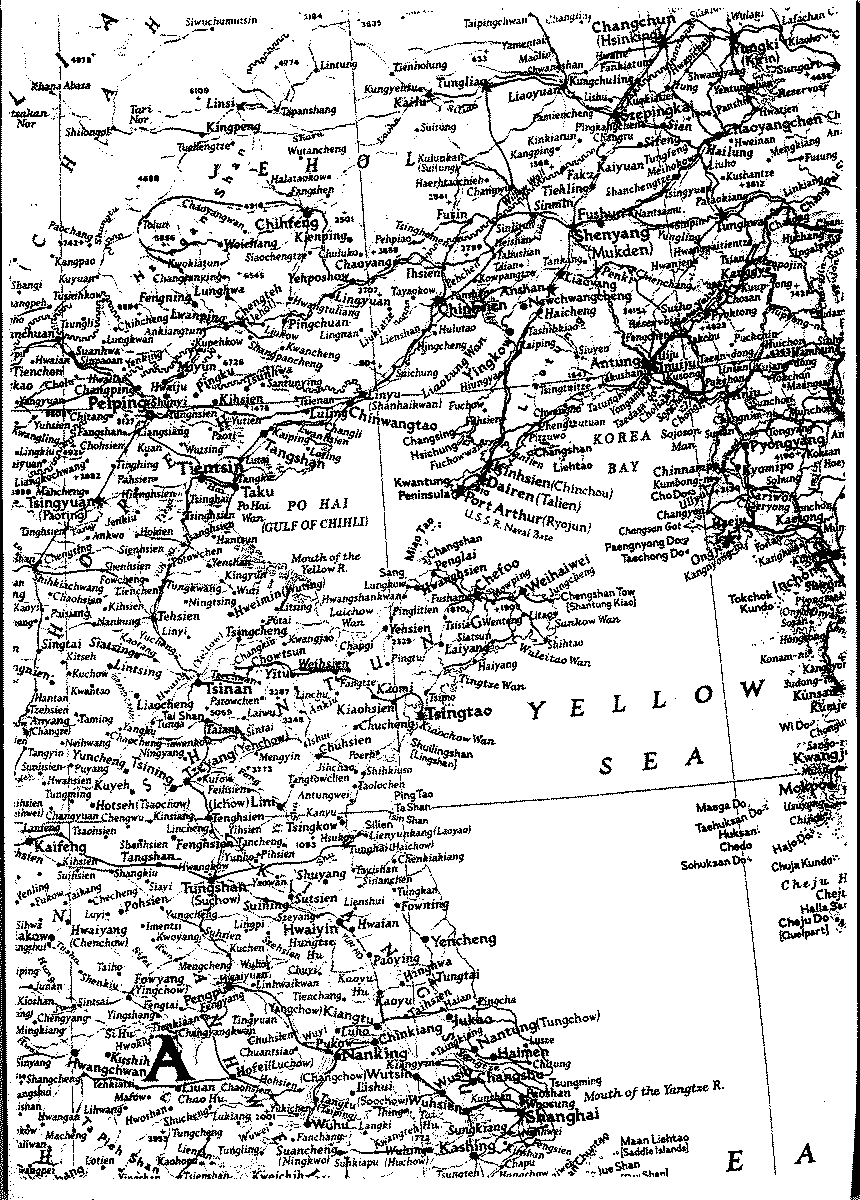

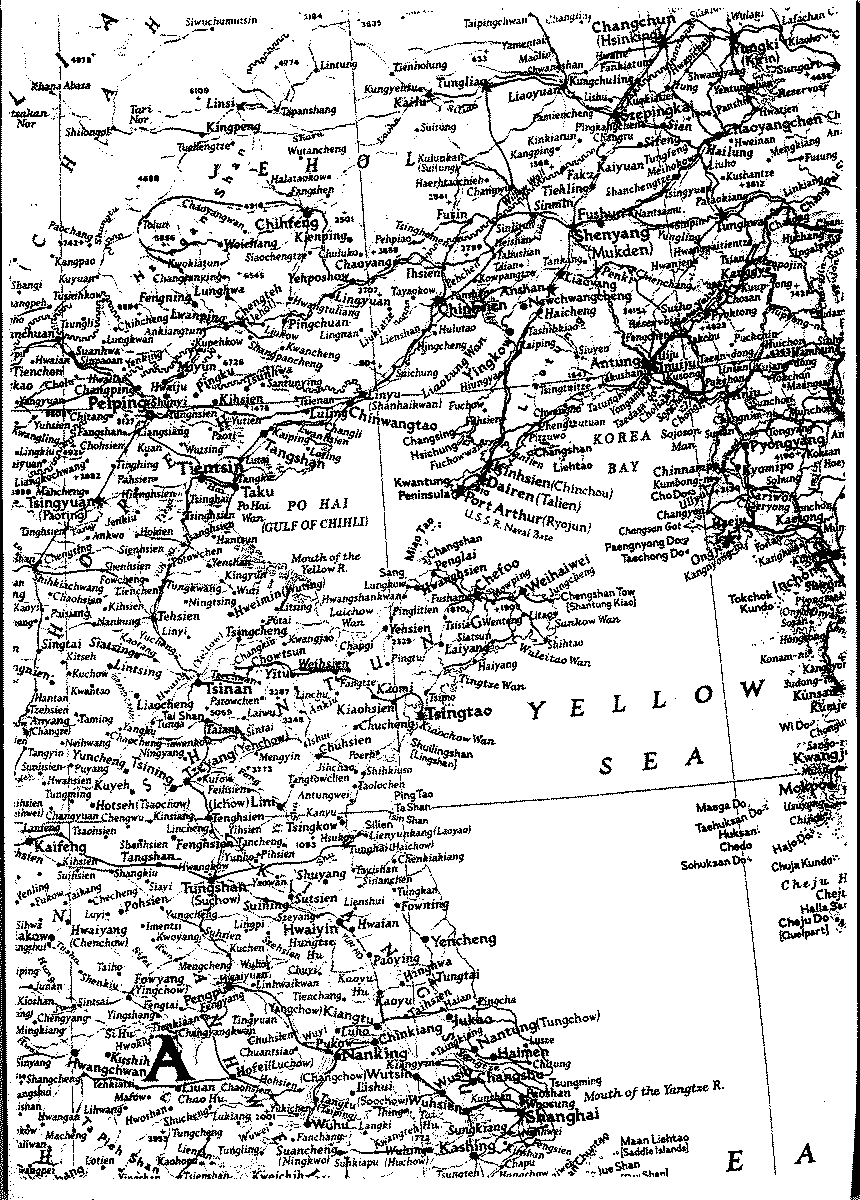

Home was Weihsien Concentration Camp in Shantung (Shandong) Province, North China.

[excerpt]

That sports day on the playing field was a speck of glitter in the dull monotony of camp life.

The youngest children ran first, then we juniors, pounding down the track barefoot, in hand-me-down shorts and shirts. Yelling and laughing, we slapped each other’s backs as we finished the course.

Then, as the veterans’ race prepared to start, a hush distilled over the crowd. Our eyes shifted to the chairman of the Camp Recreation Committee, who was starting well behind the others as a voluntary handicap. “He can never make up that distance!” gasped a boy beside me.

[excerpt]

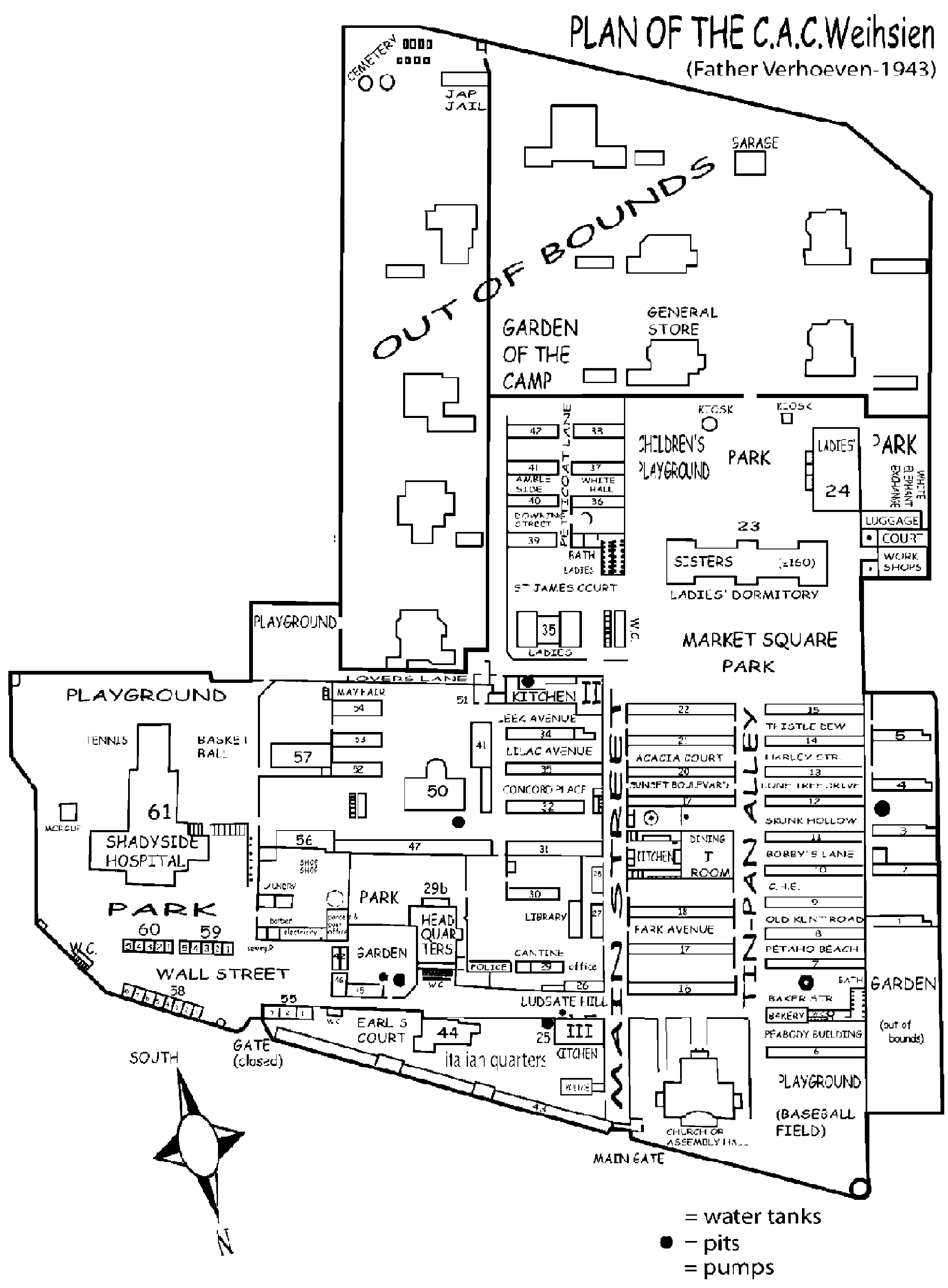

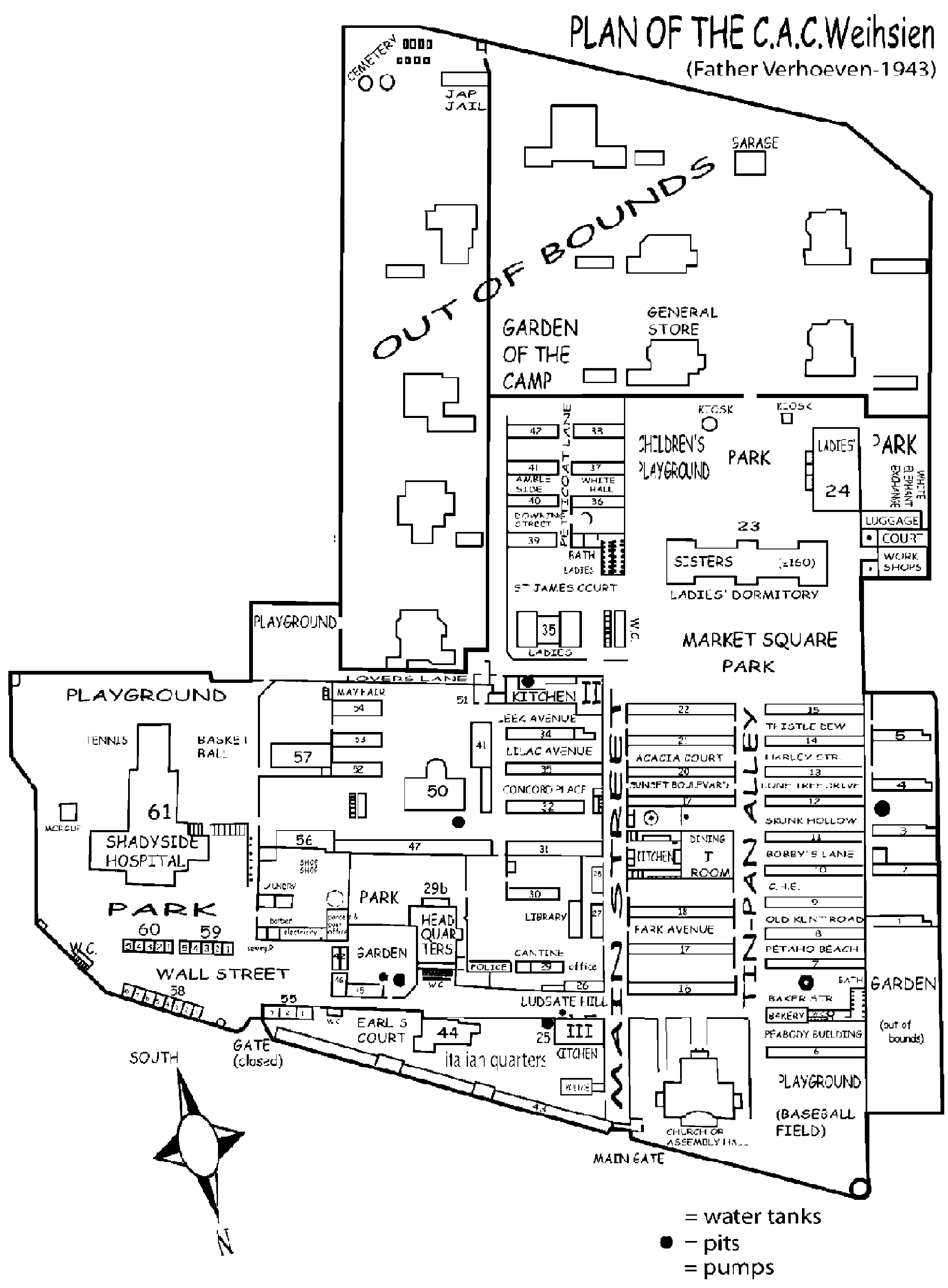

Already more than a year had passed since our school had been marched in under guard to join the rest of the prisoners. There were over two hundred of us, children of missionaries, separated by war from parents who were working in inland China, in regions not yet taken over by the Japanese. Business people, tourists, entertainers, and their families as well as children from other schools made up the rest of the prison population.

More than a third of the internees, in fact, were children. For all of us life was confined within the high brick walls that ran around the Weihsien compound.

The Japanese guards, with bared bayonets, were never out of sight by day, pacing along the foot of the forbidding gray walls or clustered at the main gates or corner searchlight towers. Even by night the searchlight beams—sweeping across the camp and over the deep trenches and coiled barbed wire— reminded us of the soldiers’ presence.

Across those trenches and outside those walls was the world, we had once known.

[excerpt]

Evelyn Davey’s diary :

Yesterday I did my first duty in an internment camp. Putting the children to bed was hectic. We had to wash in relays, and all face flannels and towels have to be handed from high pegs. Hot water has to be carried from the boys’ washing room (the old servants’ ....?) to the girls’ washing room (Miss Beagle’s bathroom); and cold water has to be carried from the girls’ to the boys’. We are only allowed to wash at night, because water is so scarce! We ate our supper sitting on cabin trunks in the hall - the Preps in their dressing gowns and pyjamas! otherwise we all eat together in two rows downstairs - all sixty- two of us. We balance plates on our knees, eat stew with a soup - and enjoy it all immensely.

[excerpt]

Now the cold weather is here and the fun has really started. I was on duty on a cold, wet, sleety day! The children had to play indoors - in their dorms and the hall. It was SOME squash! I wandered around stoking stoves, answering questions, quelling quarrels, finding paper, pencil, glue, string, etc. “raving” at people for walking on the beds, and emptying “chambers”! They could not go to the outside lavatories because of the snow - so I was kept busy. To crown all, the electric lights failed to come on, so we had to go to bed by candlelight. I had just escorted eight little girls into the bathroom to wash, holding a very wobbly candle, when the candle overbalanced, fell behind the geyser, and left us in complete darkness. I took a step forward to find it - and knocked over a jug of cold water which swamped the floor! Oh dear! Poor Teacher on Duty!

However, the day ended at last!

Yesterday we had an epidemic of children being sick. Dorothy spent the day washing out innumerable sheets, dressing gowns, pyjamas, pants and other garments.

We have a communal bath system for the children. They all wash all over using their own basinful of water, and then we

have a common rinsing tub.

[excerpt]

We noticed in the camp quite a lot of children, who gave us smiles that seemed to say they understood what we were coming to. We later made good friends of many of them, most students from the Peking and Tientsin Grammar Schools, which carried on as did our own Chefoo School in camp.

That first day we were led to the open area to the west of the Mateer Memorial Church, which was beside the main street, not far from the main gate. After the guards checked to see that we were all present and correct, and after they read the camp rules and regulations to us, we were allotted rooms or dormitory numbers. Families of four were given one tiny room while those with six members usually managed two rooms. The rooms were practically bare, but after our baggage arrived a week later traces of personality began to appear. Many people’s baggage was stolen en route or arrived badly damaged. Nevertheless, through the ingenious efforts of those with handyman skills, makeshift furnishings gave an amazingly homey appearance to our new quarters.

We younger children and our teachers were assigned to Block 24, one of the large buildings of classrooms. The only accommodation that could be spared for us was two rooms in the basement. We deposited what we were carrying, wondering, however, we would all be able to sleep in such a small space. There was no time to solve the problem as supper was ready at kitchen number one. The menu was onion soup, dried bread and pudding made with flour and water. As a special treat for new arrivals sugar was included. We were so hungry we thought it was a good meal.

[excerpt]

We children learned to amuse ourselves with simple activities. Because one game we invented required buttons, it wasn’t long before our clothes were pretty well all buttonless. Stringing the buttons on lengths of string, we spun them round, producing all sorts of variations in their gyrations. One day a teacher picked up 26 buttons off the floor.

It was really amazing what value became attached to such simple possessions. I remember one Christmas receiving a grubby old cotton spool, and you would have thought I had been given a bicycle!

Walking became a favorite pastime. Some of us were able to boast of having walked a grand total of 63 miles. An elaborate wall chart recording our scores was our pride and joy.

[excerpt]

Also among the internees were some entertainment groups which were part of the Western community in the big cities in North China. A black jazz band added quite a bit of life to camp. In fact, for us younger children from Chefoo, who had known nothing but a very sheltered missionary environment, it was our first sight of a black person! And to come face-to-face with glamorous models wearing lipstick and high heels was mind-boggling!

[excerpt]

“As the diet was lacking in calcium (no milk, no cheese, no ice cream),” Evelyn Davey remembers,

“we collected the shells from the black-market eggs, ground them into a powder and fed it to the children by the spoonful. We also gathered certain weeds around the compound and cooked them into a spinach-like vegetable to supplement the rations. Fruit, apart from a few apples, was almost unknown, and one little girl in school asked, ‘What is a banana?”

[excerpt]

The laundry was one of our chores. Three days a week a dawdling line of the younger children could be seen weaving its way back from the hospital to our rooms in Block 23, with basins of wet washing on our heads or in our arms. One time I tripped and had to detour by the pump to give everything another rinse and wring out before delivering the goods to the teachers for hanging out on the line.

[excerpt]

The medical accomplishments of camp personnel were remarkable and courageous, taking into account the lack of facilities, equipment, and medicines. Doctors performed many major operations and numerous minor ones. During our twenty-five months of imprisonment 32 children were born, and 28 people died. Had it not been for the Trojan efforts of the Red Cross in getting altogether unprocurable medicines into camp to us by the most creative means, we would have fared much more gravely. It truly was the goodness and grace of God in His loving, providential care of us, and many a time and many a person testified publicly to this.

Living in the cramped conditions of camp required much patience and consideration. The rules of one of the women’s dormitories in Block 23, which had eleven people in a space about 25’ by 15’, were as follows:

1.

Poker must be laid at right hand of the stove.

2.

Wood must not be dried in front of fire.

3.

The axe edge must be turned away from the room.

4.

Children must not visit in rest hour.

5.

No “foreign body” must be put in the highway.

6.

You must be in bed before “lights out” (10 p.m.).

7.

Mats must not be shaken on the balcony.

[excerpt]

Some of our teachers helped to teach in the other schools organized for children in camp. Evelyn Davey taught at the kindergarten that was organized. She describes her pupils:

The children were of many nationalities. Some of them were from missionary families; some from business families from Peking and Tientsin.

Julienne was English. She was always the perfect lady. Her brown hair was swept smoothly back from her face, and her clothes were always neat. She never pushed. Her father was an executive of the Kaoliang Mining Company.

Jeannette was quick and volatile. She had a Belgian father and a Ukrainian mother. She spoke both languages, and also the Chinese dialect used by her amah [babysitter]. She learned English in six weeks.

Margaret was a big five-year-old who liked to “mother” the others. She was Scotch and spoke with a soft brogue. Her father was a missionary of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Janet had the curliest hair, the brownest eyes, and the frilliest dresses in the class. Her daddy played in a dance band in Tientsin.

Mickey Patternosta was Belgian. His favorite occupation was getting on top of a wall somewhere with some like-minded friends, and seeing who could spit most accurately.

[excerpt]

For a number of months, catching flies was the number one pastime in our spare minutes in lineups or when watching the ball games. My greatest feat was what I called my best Sunday catch—sixty-six during one Sunday school lesson! Although we younger children made quite a dent on the fly population, we didn’t win the prize. We were outdone by the older boys whose methods of operation were on a larger scale.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/aBoysWar/p_FrontCover.htm

#