- by Sr. M. Servatia

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

We were told to line up and were then given a number which was to be worn for identification. We were told that we were now “Enemy Citizens” and that we would have to abide by the laws given us but fortunately, there would be freedom of religion as an enemy subject.

We were told to line up and were then given a number which was to be worn for identification. We were told that we were now “Enemy Citizens” and that we would have to abide by the laws given us but fortunately, there would be freedom of religion as an enemy subject.

This was our first Roll Call and we were to have hundreds more.

The lights would be controlled by the Japanese and we were not to turn them on or off. They did have a system of electric lighting, admirable for that part of the country at that time, in which all lights went off or on at the same time.

[excerpts]

When we first came into the camp, we noticed the leftover furniture in heaps outside the buildings.

Obviously, the former missionaries had much more than what was left there and it will never be known how much had been carried out before we arrived. In no time it was all gone as everybody took what they wanted to furnish their bare rooms.

I got a stool and that stool was worth its weight in gold to me. I didn’t need it so much in the room because you could always sit on the bed boards, but when you had a one- or two-hour roll call each day and had to stand in the open, a stool was about the most welcome thing in the world. Also it was convenient when you went to the evening lectures held out under some tree. We needed tables for the altars and during the day it could be used to store the things ordinarily found on the tables.

[excerpts]

Punctually at 7:30 each morning someone went through the camp ringing a hand bell, which was evidently one of the old school bells, to summon us all to roll call.

Everyone was required to attend and if a person was too sick to go, he had to be reported by a friend and the Japanese “counter” would go to the home to verify the statement. The same procedure was used for those on duty at the stoves, kitchen, or other important places because everyone had to be counted.

Sometimes the count would be wrong in one place and all would have to be recounted. Sometimes the “counters” would be late. The best thing was to take a book or some work along. You might see a lady bring along a dish of apples to peel if she had been fortunate enough to get them, and someone might go over to sit next to her, just to get the smell of them.

Sometimes the teenagers would bring their accordions or harmonicas along and there would be singing. Once we got a longer roll call because the boys were using slingshots and one hit a lady right in the eye. She had to be taken to the hospital immediately and lost the eye and that of course, slowed everything up.

At another evening time roll call while waiting for the “counters”, the boys were standing alongside a building trying to see how high they could reach. One of them, Brian Thompson, a sixteen-year-old who that day they said had made a wonderful witness of Faith in his morning service, challenged the others to reach a wire above him.

He reached out for it and was immediately electrocuted, as it had been a live wire. The mother was nearby but they rushed the boy to the hospital just to keep her from shock. We did not know why our roll call was lasting so long until we found out.

If it rained the “counters” would try to hurry, and you took your umbrella.

[excerpt]

Breakfast was served at 8:30 A.M. or after roll call was held.

We queued up for it, bringing our dishes and if you happened to leave the dishes there by mistake, they would be gone quickly.

Although arriving early meant waiting in line you could always converse with your neighbor and sometimes the queue conversations would get rather animated.

For some reason the Japanese never entered the dining room. For breakfast the fare was usually bread cut up and cooked in water and a little sugar, and tea.

Coffee was out of the question entirely.

Dinner was served at twelve noon, and it meant another wait in line, but it also meant another chance to get acquainted.

The serving was usually just a ladleful of stew, a spoon of vegetable, occasionally a kind of dessert. The evening meal, which was “tiffin” (someone brought in the word and it stuck. I think it may have originated in India) was a little less than supper.

[excerpt]

In each room there was a little stove and we were given a ration of coal. In April it was announced at roll call that the guards had orders to remove the stoves. Underneath the stoves were sheet-iron pans and someone had suggested that these might be nice for ironing, so when they came to our place I asked the guard if I could keep two.

We expected the stoves would come back in the winter if we were there that long. I told him I would take good care of it, explained why I wanted it, and that if he needed it at any time he could come and get it. He was most obliging and I kept them until we left. The pans came in very handy for the church wash, and I could even get the long altar cloths ironed by folding the cloth and laying the two pans together in the sun. The wash had to be laid out flat and the hot sun was enough to dry it and the underneath came up nice and shiny, as if laundered.

Handkerchiefs came off better than if ironed. Of course, while I had the pans out in the sun I would have to take a book or something to do and watch because we had all kinds of people around and some could not be trusted.

We had brought wash lines along and sometimes the wash would be taken off the line if not watched.

[excerpt]

On June 10, very quietly the news went around that two of the men, Tipton and Hummel, had gone over the wall to the Chinese guerillas and by that time they were quite far away.

The Japanese did not yet know it. They had left early and a friend had excused them from roll call. The next morning they could also be excused possibly, but then the guards would be getting suspicious. By the time the guards caught on, it was too late to find them. The escape angered the guards and they decided that in order to tighten up, we would have to have two roll calls daily, so another was added to the late afternoon before Tiffin.

We knew what that meant; standing another hour every day, but the two men could not foresee this.

One of the priests [NDLR= Father Raymond deJaegher], who knew more than anyone what was going on outside was determined to go along with them, but Father Ildephonse [NDLR= Father Rutherford] refused him permission, saying that if he left, he would be excommunicated, so he did not go.

However, for two days all the men whom the Japanese thought might know anything about the escapees were kept in the church and no one else was allowed in.

They were questioned by the Japanese, but of course, the men knew nothing and were finally released. At the roll calls one day, they asked us each to yell out our number, instead of them calling the number and we, answering present, as had been done until then. When it got to 222, the young man who had it screamed out “toot-toot-toot” and, of course, the whole group broke out in laughter.

The guard didn’t know what was wrong, but he told the interpreter to tell us that we weren’t supposed to laugh at roll-call. By this time we were so used to roll calls that we didn’t mind it, and besides you could get quite an amount of work done, unless it was too cold, or raining.

[excerpt]

On the 2nd of February, Mr. Liddell, our faithful friend and interpreter passed away.

We mourned him, attended the funeral service and he was buried in the cemetery, one of the twenty-nine who were to swell the number of the former missionaries who had been buried at the camp before we arrived on the scene. Someone else took his place at roll calls. While we did not talk usually to our guards, they seemed more friendly.

Perhaps they realized that they were losing the war, but at least they knew much more than we did, and maybe they were glad the war was coming to an end. Certainly, they could feel much happier than their brothers out in the war zone or those even in Japan because even Tokyo was getting its bombings.

I don’t think we ever needed to be afraid of the guards, even at night. Out alone at night I should have been afraid of some of the people on our side, more than of the guards because we had people of all walks of life and some of these walks weren’t the most admirable.

[excerpt]

One of the guards was more or less disliked by the internees.

It seemed whenever anyone asked him for something, the answer they got was “bu-hsing”, which in Chinese means “not-do,” in other words “it won’t work.”

So the camp dubbed him “Bu-hsing”. One day a little puppy came into the compound through one of the holes. The children grabbed it, and at last they had a pet. They fed it and took care of it for a few weeks. They called it “Bu-Hsing”. It happened that big “Bu-hsing” was walking along the street towards the guardhouse, when a little child called “Bu-hsing”. The Japanese love children and he felt rather flattered that the child was calling him, even though she did use his nickname, but then, turning around, he saw that the child was calling the dog which was directly behind him. Angrily, he grabbed the little dog and threw it over the wall.

The children managed to coax the dog in again, but after that they kept him hidden.

[excerpt]

March 1945 came in like a lion, with rumblings about the war in Europe and the Allies imminent victory and the men took to betting again.

On the night of March 30 or 31, we were awakened at midnight by the big bell on top of our building ringing loudly.

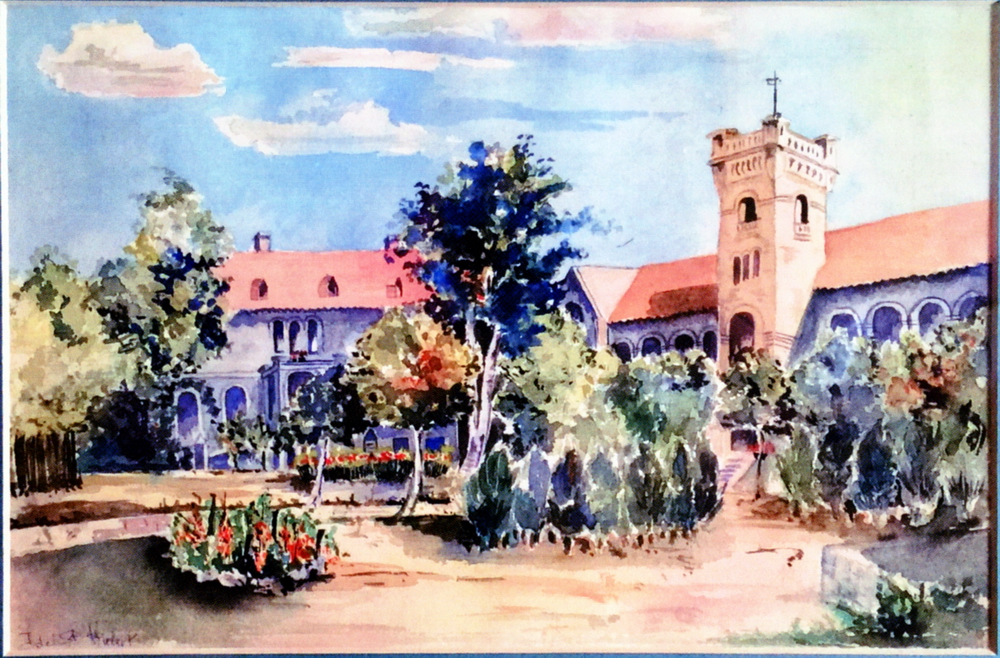

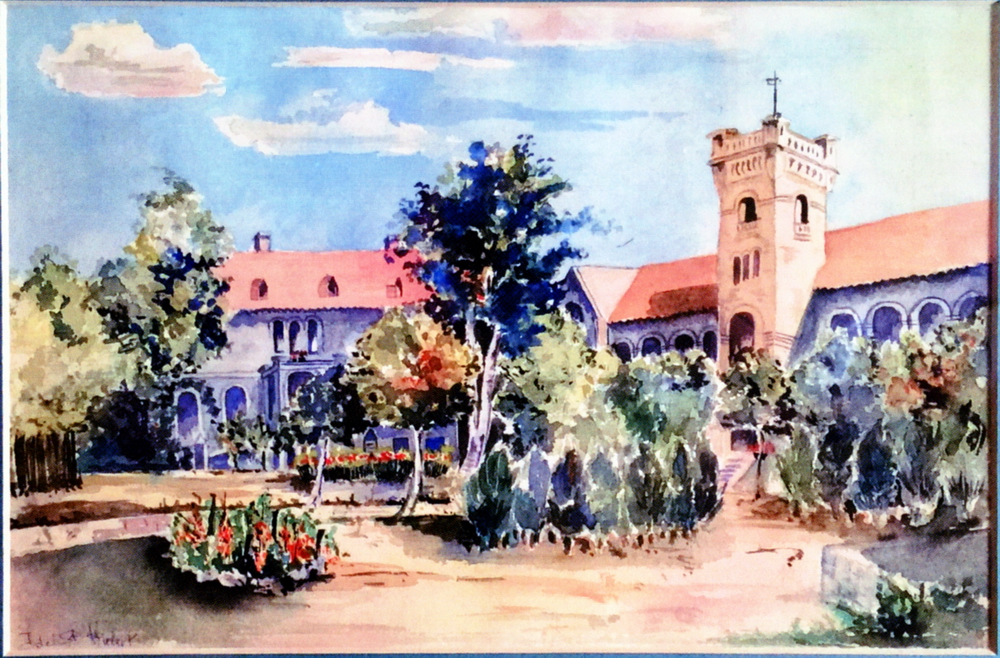

Suddenly all lights went on and then the roll call Bell Tower : Block-23 bell. Someone was going through the compound ringing it.

We all got up.

It could mean nothing else than roll call but why in the middle of the night? We shuddered at the thought of an hour out there in the cold and we shuddered more at the thought that this might be our final end, perhaps we would never return to this room.

All of us knew how the Japanese had taken whole villages of Chinese out to the threshing floor and shot them down with machine guns.

Was it our turn now?

Quickly we dressed, and we prayed. We took blankets and everything possible along. Everybody out on the plaza was as perturbed as we were.

No one had any idea what it was all about. We sat there anxiously waiting for the guards.

Finally, they came, three of them. They were very animated and angry. They fairly yelled at the interpreter and he interpreted, “They want to know who rang that bell?” One young man called out “I wish I had!” and everybody laughed. The tension was broken.

But the question remained about the bell ringing in the tower . . . who did it? No one knew.

We were counted and told not to laugh during roll call. Then they went to the other groups to check. It was a long time before they returned. In the meantime, the young people began to dance.

One had brought his accordion and there in the cold night the rest of us huddling in our blankets as the young folk were dancing to keep warm.

It angered the guards that they could not find out who rang the bell. We were told to go back to our rooms which we did willingly, still wondering.

The next day word was passed around quietly that Germany had fallen and one man had bet another that he would ring that bell at midnight if Germany fell, which he did. He confessed and it was all taken care of quietly and the camp in general did not even know who he was. But the Chief of Police whom the internees called “King Kong”, and who had been expecting a promotion, lost face by the incident.

The ringing of the bell had scared him too and he had surmised a riot and had called for help from the neighboring troops. Of course, when they came they weren’t needed.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Servatia/p_FrontCover.htm

#