by Mary L. Scott

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

It soon became apparent that one of the greatest needs for the internees was for a working hospital. There were sure to be illnesses in our community of nearly 2,000, particularly with the unsanitary conditions under which we lived. Rumor had it (and I can’t verify it) that the Japanese had used part of the original hospital building as a stable.

It soon became apparent that one of the greatest needs for the internees was for a working hospital. There were sure to be illnesses in our community of nearly 2,000, particularly with the unsanitary conditions under which we lived. Rumor had it (and I can’t verify it) that the Japanese had used part of the original hospital building as a stable.

Nothing daunted, the doctors and nurses in camp and many volunteers, including Mr. Moses who had been business manager of our Nazarene hospital in Taming, began the herculean task of cleaning up and salvaging what equipment they could from piles of debris scattered about everywhere.

Within eight days, the hospital was functioning sufficiently to feed and care for patients, and in two more days the operating room and laboratory were ready for use.

[excerpt]

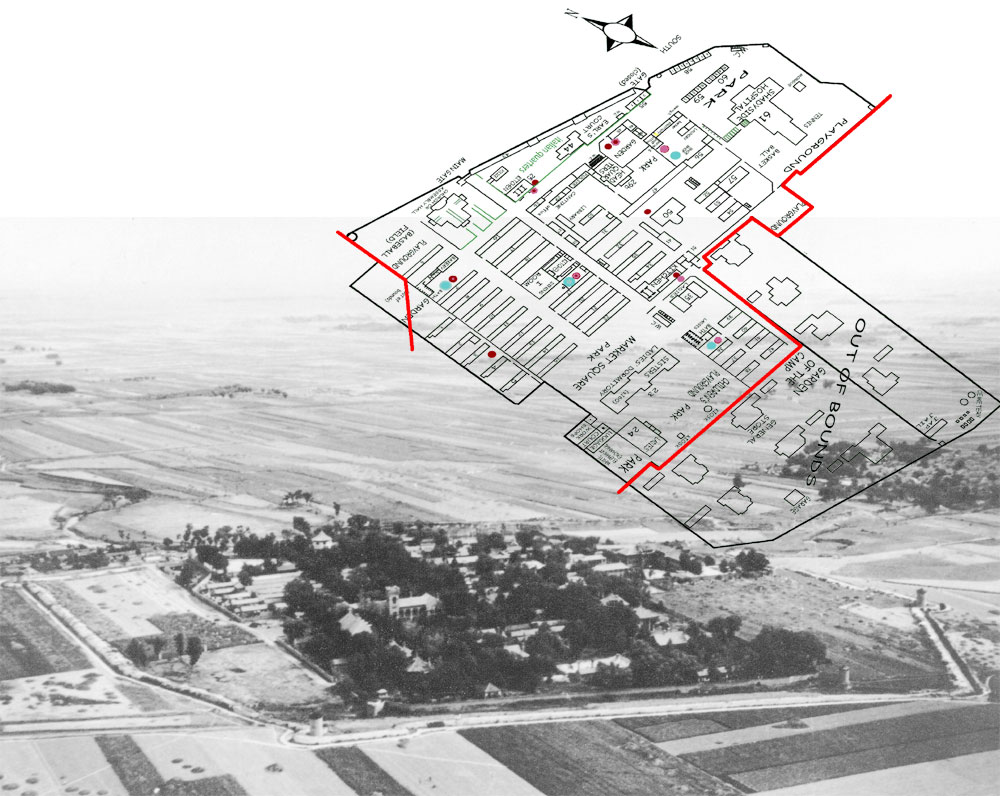

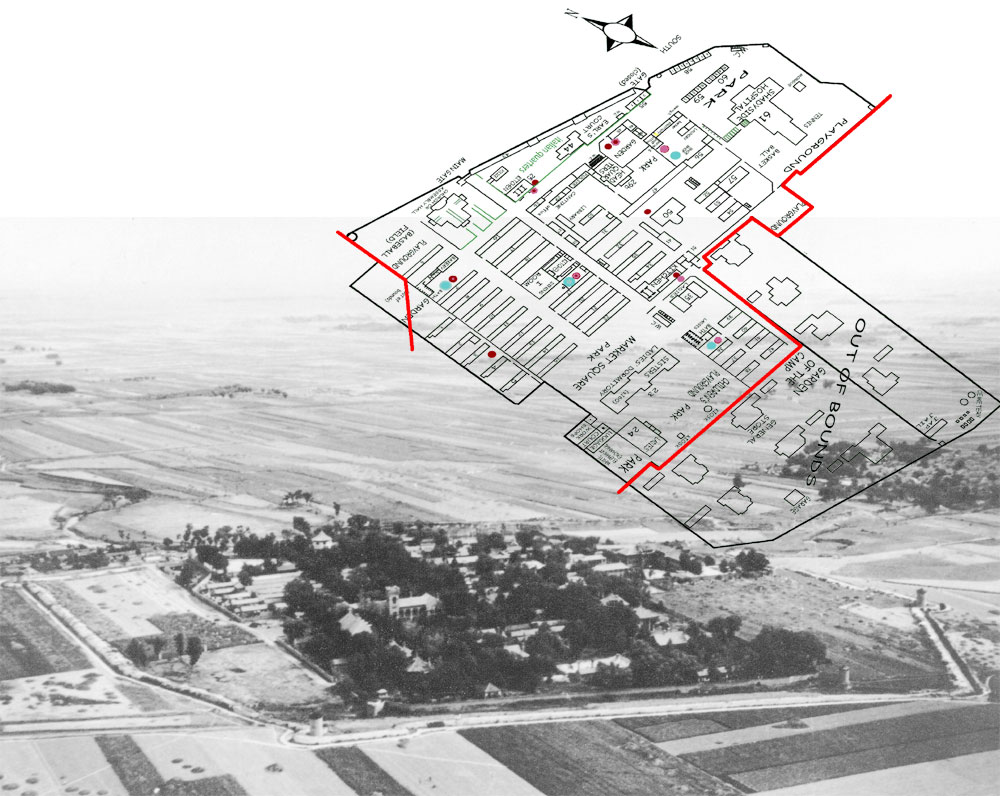

Our camp was actually what had once been a beautiful Presbyterian mission compound. It was a little over six acres in size and had housed a well‐equipped high school with classrooms and administration buildings, a church, hospital, bakery ovens, three kitchens, and row after row of 9 x 12foot rooms used to house the resident students.

The buildings seemed to be undamaged, but the contents were a shambles. Refuse was piled outside the buildings or strewn along the driveways by the garrisons of Japanese and Chinese soldiers who had been billeted there.

Our immediate task was to clean up the place. It was a mammoth undertaking but the people had a mind to work. Besides, there were valuable broken desks and chairs that could be used if repaired.

Scrounging, looking anywhere, even in rubbish heaps to find something usable, became an everyday operation.

[excerpt]

The Medical Committee had the jurisdiction of the hospital and general health services of the camp.

Tests of the water from all the wells revealed that it was necessary to boil all drinking water. It was an enormous task for the kitchen crews to provide drinking water as well as boiling water for tea at least twice a day between meals.

The Medical Committee discovered that the water from one well in camp was not safe to drink even after boiling for 30 minutes. It was used only for washing.

[excerpt]

We were granted full religious liberty as long as the Japanese authorities were informed when and where services were being held. On Sundays the church was in use all day.

The Catholics gathered for early morning mass, and the Anglicans had a service at 11 a.m.

Our smaller holiness group met in a room in the hospital building. At four o’clock in the afternoon a union service was held. The messages delivered were evangelistic, conservative, or liberal, depending on who was in charge.

The Evangelistic Band, formed early in camp, sponsored a Sunday evening singspiration. Old and young, Protestant and Catholic, attended. A short but pointed gospel message followed the singing.

Ten people were definitely converted through these efforts. And we prayed earnestly for the Japanese guards who slipped in occasionally.

Though they might not understand the spoken language, we prayed that they would understand the language of the spirit of love which held no malice or resentment.

After the many initial adjustments we led quite a normal life on the 6.2 acres assigned to us behind the eight‐foot wall. Work, recreation, and social and religious activities filled our days and evenings.

[excerpt]

There were four main sources of our food.

Major and basic was the Japanese issue of food which was delivered to our supplies committee and distributed to each of the three kitchens (only two after the Italians came) and the hospital diet kitchen.

By common agreement the diet kitchen had first claim to the supplies needed by the patients in the hospital or those on special diet by doctor’s orders.

Storekeepers in each kitchen kept close watch over the supplies, especially the oil and sugar.

[excerpt]

One great need was milk for the children. When confronted with this request, our commandant arranged to get cow’s milk brought in, which was properly sterilized in our hospital kitchen and distributed to families with children three years old and under. Sometimes there was just a small amount in the bottom of a cup, but at least an effort was made to supply the need for fresh milk for the children.

[excerpt]

While the hospital doctors and nurses often worked around the clock, since there were no others who could spell them off, there was no way they could produce nonexistent medicines.

They suggested substitutes like ground eggshells to put in the children’s cereal to provide calcium. The Peking medical personnel had also given adults a quantity of bone meal to bring into camp.

But other than the few medicines that were made available through comfort money and the Swiss consul, little could be obtained.

Our need was at least partially met through the escape of two young internees who went over the wall one dark, June night in 1944. Tipton was a Britisher and Hummel was an American. For days before their escape, they sunned themselves for hours to get rid of the telltale white of their skin.

Successful, with the help of others, in getting over the wall, they joined a group of guerillas in the nearby hills. The escape caused quite an upheaval. From then on there was roll call in specified areas twice a day instead of the usual room check.

Roommates of the two escapees were held in the assembly hall incommunicado for several days as Japanese officials tried to pry information and confessions from them concerning their knowledge of the escape. They were moved from their pleasant rooms on the upper floor of the hospital near the wall to less desirable quarters in the center of the camp.

Tipton and Hummel were able to report to Chungking by way of radio that we were in very urgent need of medicines.

In response, the American air force made a drop of four large crates of the latest sulfa drugs to the nationalist guerillas nearby.

The next night a guerilla, disguised as a Chinese coolie, called at the Swiss consulate in Tsingtao and informed the consul of the drop and told him that they would deliver the four crates to him the next night at 2 a.m.

True to their word, four men, each carrying one large crate, appeared at 2 a.m., then slipped away into the night. Now the question was, how could these supplies be delivered?

The Swiss consul, as the official representative of enemy nationals in Shantung, was the only outsider (except the night soil coolies) allowed into our camp. Taking in the usual comfort money and a few available medicines once a month was a simple procedure. But to take in four crates of medicines, much of which the Japanese knew was not available in Tsingtao, would be a very complicated affair.

Finally he devised a plan.

He had his secretary type a list of medicines available in Tsingtao, leaving four spaces between each item. The Japanese authorities, though puzzled by the spaces, put their official seal on the papers.

Then back at the consulate, he had his secretary, using the same typewriter, fill in the blank spaces with the names of the other medicines in the crates. The next day he arrived at the gates of the Weihsien Camp with the crates. While the Japanese wondered where all these medicines had come from, they finally gave their O.K. since there was no doubt about the consular seal and signature at the bottom of the list.

The carts rolled into camp and proceeded to the hospital to deliver their precious cargo.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/KeptInSafeguard-MaryScott/MaryScott(web).pdf

#