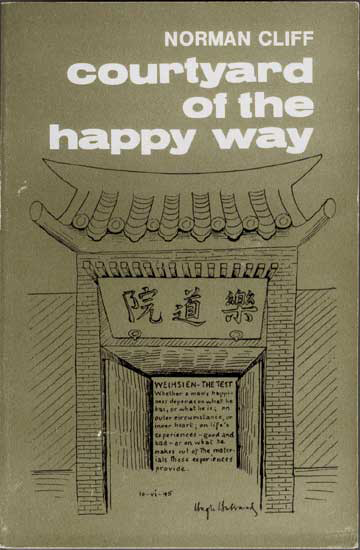

- by Norman Cliff

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

These first internees had set to work with that resourcefulness and determination characteristic of the human race when looking for the basic comforts of life.

These first internees had set to work with that resourcefulness and determination characteristic of the human race when looking for the basic comforts of life.

They cleared roads, cleaned the rooms, opened up three big kitchens (Kitchen I for the Tientsin community, Kitchen II for those from Peking and Kitchen III for Tsingtao internees), each feeding five hundred people.

Catholic priests from Belgium, Holland and America, mostly in their twenties, cleared the toilets and erected large ovens for the camp bakery.

[excerpt]

It was quite evident that the four hundred Catholic priests and nuns had made a great impact and profound impression on the internee community. They had turned their hands to the most menial tasks cheerfully and willingly, organised baseball games and helped in the educational programme for the young.

But inevitably romances had been formed between admiring Tientsin and Peking girls and celibate Belgian and American priests from the lonely wastes of Manchuria.

Anxious Vatican officials had solved the delicate problem by careful negotiations with the Japanese, as a result of which all but thirty priests had been transferred to an institution of their own in Peking where they could meditate and say their rosaries without feminine distractions.

Their departure had left a vacuum in effective manpower for such tasks as pumping, cooking and baking.

Thus the arrival of our Chefoo community aggravated the situation further, for out of the three hundred of us only about two dozen were potential camp workers, the remainder being school-children and retired missionaries.

[excerpt]

Another source of nourishment in the early period of internment was the parcels received by the missionaries from their stations in Peking, Tientsin and other places. Catholic nuns and priests received what seemed to us wonderful luxuries on a grand scale.

Protestant missionaries did not fare nearly as well.

[excerpt]

After the departure of the bulk of the Americans and Canadians for repatriation, and the transfer to Peking of the majority of the Catholic priests and nuns, as well as the arrival of our Chefoo community, there was a new “mix” of race, age and social grouping.

Sixty per cent were British, twenty per cent American, the remainder being a number of minority groups such as Belgian and Dutch.

Later we were to be joined by a hundred Italians after their country had capitulated to the Allies. Regarding them as “dishonourable Allies” in contrast to ourselves, who were “honourable enemies”, the Japanese placed them in a camp within a camp. They were interned in a block of houses behind the guard room, and at first were not encouraged to mix with the rest of us, but as the months went by the difference in status was dropped.

By profession and occupation there was first of all a large missionary community representing the entire spectrum of Protestant and Catholic missionary traditions; then there were top executive business men, and their families, employed by the major industrial and commercial companies, a group previously enjoying a high standard of living in Peking and Tientsin.

Largely from Peking were educationists and language students who had come to camp from the cloistered walls of university and college.

Last but not least, the camp included some of the drop-outs of Western society, who had run away from their past in a more sophisticated environment to enjoy the wine, women and song of North China’s underworld.

A well-known group in Far Eastern society consisted of White Russians who had fled from the 1917 Communist rising in Russia, stripped of land, wealth and status in the revolution which swept their motherland. In China they were a pathetic stateless people with little economic or social security. Many Russian women found security in marrying British and American business men. Some of these were in the camp. Fearful of revealing their earlier background of poverty and manual labour, they were loath to turn their hands to some of the less attractive tasks which camp life demanded, while the wives of British and American top brass executives readily did so; but it was quite foreign to their easy-going life before the war.

There were other internees of mixed blood-half Chinese, half Japanese, half Filipino.

There were four American Negroes who had been bandsmen in a Tientsin nightclub.

Among the various races were prostitutes, drug addicts and alcoholics, who found their particular moral weaknesses severely cramped in the Weihsien style life. Inevitably in such a community a few individuals stand out in my memory for their foibles and peculiar personality traits, or their uncommon saintliness and integrity.

[excerpt]

From the Roman Catholic priests (whom I greatly admired and came to regard as among my best friends in the camp-though I could not grasp the significance of their rituals and dogma) I had learned the habit of walking back and forth in the open for prayer and meditation. Kneeling at my bed to pray tended to put me to sleep from sheer exhaustion.

Into this situation came what I have come to regard as milestone number three in my spiritual pilgrimage. Back in the old Prep. School playground in Chefoo praying with a classmate on that Saturday afternoon eleven years previously, I had suddenly seen that God has no spiritual grandchildren, and that Christ was on the Cross for my sins and failures. Four years earlier was milestone number two when Father had baptised me on that summer day in 1940 in the bay in front of the schools, while the crowds on the beach were singing:

“Follow, follow, I will follow Jesus, Anywhere, everywhere, I will follow on ... .

[excerpt]

The more devout internees gave vent to their happiness in services of thanksgiving at the church in various traditions of Christian worship ? Catholic, Anglican and Free Church. The Edwardian style church, which had served at various times as school, prison and distribution centre, was now (as it had often been during the darker years of internment) the focal point of worship and heartfelt praise to the Lord.

[further reading]http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/Books/Courtyard/eDocPrintPro-BOOK-Courtyard-01-WEB-(pages).pdf

#