- by Laurance Tipton

[Exerpts] ...

[...]

The camp was by no means ready for occupation by such a large group of people, and even the Japanese themselves realised that there was yet much to be done.

The camp was by no means ready for occupation by such a large group of people, and even the Japanese themselves realised that there was yet much to be done.

Reluctantly, therefore, they allowed specially selected gangs in to complete the necessary repairs: cesspool coolies to whom they had sold the sole rights on this popular form of fertiliser, a tin-smith to make pots, pans and buckets for the use of the kitchens, and a group of carpenters.

At first these workmen were not searched very closely and several of the carpenters used to fill their toolboxes with eggs. In order to keep in close touch with these men, I made a regular contract for a couple of dozen eggs a day in an effort to gather what information I could regarding conditions outside the camp, but either they knew little about them, or refused to talk.

Having eventually gained the confidence of my egg man, I decided to have some Chinese clothes made, realising that it would be far too conspicuous to wear foreign clothes if one wanted to try and escape. Cloth was very expensive, and feeling that I should conserve my funds, I gave him a pair of sheets, which he agreed to dye black and have made into a Chinese jacket and trousers by his wife.

In due course he came into the camp wearing the jacket over his own, which aroused no suspicions, as the Chinese wear from one to six layers, depending upon the temperature. The trousers, he promised, would be forthcoming in a day or so.

As his work took him to various sections of the camp, and since at that time I was working in the butchery every morning, it was arranged that he should throw them through the back window of our room which overlooked one of the much-used footpaths of the camp.

One morning our neighbour, the Bishop of the Anglican Mission was lying on his bed reading when, suddenly, a pair of black trousers came flying through the window and landed on his chest. The Bishop’s immediate reaction was one of righteous indignation.

“Evidently,” he thought “someone has stolen these trousers from a washing-line and, being caught in the act, has thrown them through the nearest window”

In a moment he was stirred to action and, dashing up the alley, made record time to the path behind our row, waving the offending trousers in the air and shouting “Thief ! Thief !”

A crowd soon gathered.

The theft seemed difficult to explain, as there was no clothes-line in the vicinity. Much speculation ensued, but no one claimed the trousers and in due course the Bishop returned, having decided that the correct procedure was to hand them in to the lost property office.

When I returned from work that afternoon, I was told the story of the mysterious Chinese trousers and, reluctantly, I decided that if I wanted my trousers the only thing to do was to own up.

So I explained to the Bishop that I had ordered them as my own clothes got so greasy and dirty in the butchery. I felt very sure that he did not really appreciate my explanation, and from that time onwards he always looked a little surprised to see me amongst those present at the morning roll-call.

The trousers having had so much publicity, I had no alternative but to wear them, and from then on they became known as “the Bishop’s Jaegers”.

There were of course several groups who from time to time interested themselves in the possibility of making a break from camp. For the first month or so C― of the China Soap Company, Arthur Hummel and myself worked on the idea.

Through Chinese working in the camp, letters were dispatched to friends outside in an endeavour to make contacts; messages were sent to Tientsin and Tsingtao, and we even sent a messenger up to Peking, but all to no avail.

We got into touch with some of the Catholic priests who, up to the time of concentration, had been working in Shantung, and received from them a lot of helpful information and sound advice, but nothing practical materialised.

Later I worked with D― who always swore that he had infallible connections.

We held long uninterrupted conversations with the black- marketeers as to the possibility of being guided to the nearest Chungking troops, but with these people such matters always revolved around the question of money. Invariably they asked for a great deal more than we could possibly raise and we never got very far with them, as their main interest was the black market.

Some months later our efforts were revived by one of the Catholic Fathers concerned in the black market. He had been in touch with someone who he was sure would help us.

Many letters were exchanged over the wall, and a certain amount of money, but once again the plan fell through.

By now it was well into the autumn and we realised that if we were going, we should have to get out before the winter set in, and as there seemed to be little hope of that, gradually the matter was dropped.

Nevertheless I continued to keep up my contacts with the Chinese workers, and when they were changed, which was frequently, they would either recommend me to their successor or to someone else who was remaining, with the result that I had outside contacts the whole time.

[excerpt]

The Committee was worried: the food situation threatened to get worse; there was no indication of comfort-money payments being resumed. Italy had capitulated, the Americans were pressing the Japanese in the Pacific, and the papers began to admit the possibility of an Allied invasion of Europe.

With the turn of the tide the position of the camp became a matter of some concern. What would be the Japanese reaction to increasing Allied victories?

Would they take it out of the internees or would they endeavour to ingratiate themselves with the camp?

What would be the final outcome?

What were the conditions outside the camp?

Communists?

Roving hordes of irregular bandit-troops?

Were there any reliable Chungking forces in the area? Would the Japanese in the camp be attacked or would they, in a mad spirit of reprisal, massacre the internees?

At this point, rumours were heard amongst those close to certain members of the Committee, of a letter having been received from a Chungking unit. There was talk of a ridiculous scheme to rescue members of the camp, on a secret airfield and relays of planes that would whisk us all off to Chungking.

This, I decided, was worth further investigation, and finding de Jaegher, we went off together to see Hubbard of the American Board Mission, who, we felt, would know all about it.

Hubbard was an extremely sound man with years of experience of China and the Chinese, a man of wide interests and incidentally the leading ornithologist in North China; I had made a practice of discussing with him the various plans which we had made from time to time.

Being on the Committee, we felt sure he would know the details of this latest development. We were not disappointed. He showed us the original letters and the Committee’s courteous but non-committal reply. The letter in Chinese received from the Commander of this Chungking unit was certainly interesting:

H.Q. 4th Mobile Column, Shantung -Kiangsu War Area.

Beleaguered British and Americans: Greetings to all. The dwarf islanders, the brigands and robbers! have upset the order of the world.

My countrymen have experienced their brutality in war and widespread calamity with human sacrifice beyond any comparison in human history. Without taking account of virtue and measuring their strength, they dared to make enemies of your countries so that you have met with great misfortune and have been robbed of your livelihood and happiness.

We can well imagine that your life in Hades must reach the limits of inhuman cruelty.

As I write this I tear out my hair by the roots.

But the Allies in the Pacific, in south-east Asia and on the mainland of China have counter-attacked with great success. I beg of you to let your spirits rise.

My division is able to rescue you, snatching you from the tiger’s mouth, but the territory we control is small and restricted and I cannot guarantee your safety for a long period.

If you will request your consuls to send planes to pick you up and take you to the rear after I have released you, then my divisions can certainly save you.

Regarding this matter I am asking Mr. Chen to find some way of getting in touch with you and to make arrangements. I respectfully hope that you will be able to carry out these plans and send you all my good wishes.

Wang Yu-min 33rd year of the Republic of China, Fifth month, fourth day (4/5/’44)

Together with this was received a letter in English from Mr. Chen :

DEAR FRIENDS,

This serves to inform you that first of all I have to introduce myself to you. I was first-class interpreter in the Chinese Labour Corp, B.E.F., during the last War. . . .

I have been in Ch’angyi just a couple of months and the first thing I decided with the Commander and the Assistant Commander is to arrange to save you all out from the camp and then send you back to your own country.

But please note that from here to Chungking is rather difficult to go right through as the Jap soldiers are all blocked up the ways. So we have to arrange to send you all back by air. In this connection, we have to send a few special men (and I myself) to Chungking to connect the matter and request the Chinese Central Government, American and British ConsulateGenerals to arrange to send down some big aeroplanes for the transportation, so therefore before we save you all from the camp we have a lot of things to do such as to build the aerodrome for the planes to land and etc.

However, after everything settled up we will let you know beforehand.

Kindly believe us that we are easily to save you all out as we have over 60,000 soldiers staying in Ch’angyi area . . . wishing you all have good luck.

Please keep patient for the time being. We may not act till the kaoliang crops grow up.

Wait! Wait! I remain, Yours very truly, S. W. Chen

P.S.—God will help us.

Subsequent letters were received, elucidating the details of this hare-brained scheme and announcing that construction of the landing field had been commenced in the area held by these troops.

As soon as the crops had grown to their maximum height, the camp would be attacked, the Japanese guards annihilated, the internees transported to this airfield and flown off by relays of planes to Chungking, where they would live happily ever after!

The Committee replied that much as they appreciated the compassionate motives behind this scheme, they feared that owing to the large percentage of women and children, the sick and the aged, it would not be a practical move and regretted that it could not in these circumstances be considered.

It was not long before a reply was received which, completely ignoring the Committee’s polite but firm refusal, announced that their representative was about to leave for Chungking and requested a letter of introduction to our Embassies.

It further exhorted the internees to be patient, for as soon as the crops were high enough to afford cover, they would be rescued.

The Committee, who had not the slightest desire to be rescued in this way, were in rather a dilemma, as, if this unit did in their enthusiasm attack the camp, there was no knowing what would be the outcome.

Something must be done to stop it.

Ted McLaren, H—, de Jaegher and I discussed the matter at great length; de Jaegher and I felt that at last we were in touch with a genuine proChungking unit and that this was the moment to which we had been working for the past year. If the matter was judiciously handled, we could obtain our objective and at the same time be of some service to the camp.

We convinced McLaren and H― that for the benefit of the camp this connection should not be ignored, and pointed out that we should work towards turning this wild scheme to some more practical form of assistance of real benefit.

From then onwards the matter was turned over to us with the understanding that we should keep them fully informed on any future developments.

We immediately sent off a letter to Mr. Chen to the effect that this whole scheme was of great importance to the camp and needed much careful planning, which could not possibly be carried out successfully through the present hazardous means of communication.

We therefore suggested sending two representatives to the Commander’s Head-quarters to discuss this matter. In due course we received a reply from Mr. Chen stating that he thought this could be arranged and he was leaving immediately for Headquarters to discuss details with Commander Wang Shang-chih and Vice-Commander Wang Yu-min.

In the meantime we had started to assemble what we thought it necessary to take with us, deciding that we would limit our gear to a knapsack apiece.

De Jaegher’s superior Father Rutherford, happened to call in just as he was re-checking the contents of his knapsack. It did not take Father Rutherford long to tumble to the idea and he forbade de Jaegher to leave. McLaren, H― and I argued with him alternately but without success.

Although entirely in favour of the scheme, he felt that he could not afford to have the Catholic Church involved for fear of consequences, not so much in the camp as elsewhere, and now that de Jaegher’s part in this plan had come to his knowledge, he had no alternative but to stop him.

He added, however, that he would of course pray for the success of the mission.

This was a great disappointment as we considered de Jaegher’s experience and knowledge of the language invaluable.

Looking around for someone else to take his place, I asked Arthur Hummel, who needed little persuasion to fall in with the scheme.

Although successive disappointments had made us some-what sceptical, we could not help but feel that this time we had the right connection and it was with eager anticipation that we kept our appointment at the wall on the scheduled days.

But for a week our man failed to come.

Then one day he appeared only to signal “no message”.

Another week passed without any news and we felt that, after all, this connection which had offered so much promise was obviously going to fall through, as had all the others.

[excerpt]

ONE Saturday morning towards the end of May 1943 [sic] — (in fact, it was in May, 1944), we received a number of Japanese English-language newspapers which the Japs let us have from time to time, and there, on the middle page of one issue, was a half-column account of a successful Japanese mopping-up operation against this very unit with whom we were negotiating.

It claimed that Japanese planes had completely demolished the Headquarters of these “bandit troops” whose forces had been routed by a Japanese expeditionary force. Ammunition and clothing depots had been destroyed and the leader of this band, Wang Shangchih, captured.

This at least seemed to prove beyond doubt the existence of such a unit. Resigned to yet another failure, we were amazed when a few days later we received a letter from Mr. Chen.

He apologised for the delay due to the large-scale Japanese attack on their Headquarters at Suncheng, during which their Commander, Wang Shangchih, had been captured and taken as a prisoner to Tsingtao. The new Commander, Wang Yumin, was still entirely in agreement with our plans and if we would advise them of the date on which we proposed to leave the camp, the necessary preparations would be made and plans communicated to us in due course.

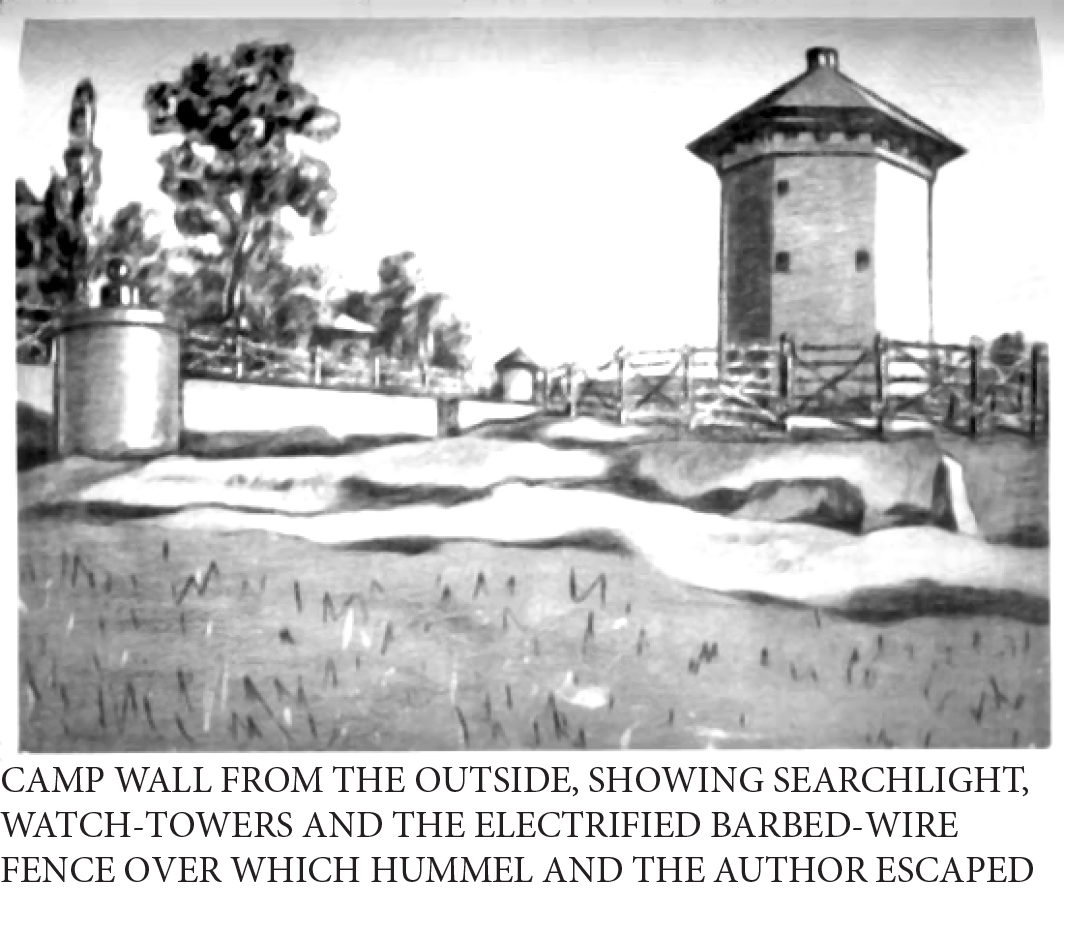

We consulted Tommy Wade as to the most suitable place to get over the wall, and it was decided that a small watch-tower in the middle of the west wall was the ideal spot. An indentation in the line of the wall obscured this section from the direct rays of the searchlight on the north-west corner of the athletic field.

It was, however, exposed to the search-light on the watch-tower at the southern end of the wall in the Japanese residential section of the camp. The guard was changed at 9 P.M. and it was customary for the new guard to make a tour of inspection along the alley-ways in this section after coming on duty. This usually took about ten minutes.

During those ten minutes we would have to make our get-away.

It was essential that there be no moon, but on the other hand we felt that a moon would be of considerable assistance to us once we had got clear of the camp ; such ideal conditions would prevail on the 9th and 10th of June, which would give us exactly one week in which to prepare.

Having decided on these two alternative clays, we replied to Mr. Chen and advised him that the rendezvous would be at a thickly-wooded cemetery a little over a mile north-east of the camp between nine and midnight on the 9th or 10th of June.

The suspense of the ensuing week was unbearable.

The knowledge that within a few days we would have finished with this futile existence made us pity the other internees who would have to endure it for the duration ; the excitement and the anticipation made us long to tell the world.

Each day passed like a week and each night a month of rest-less tossing and turning.

As part of our plan to help exonerate our room-mates, we started to sleep outside, as many people did during the summer months. This would at least clear them of the blame for not reporting our absence if our beds were found empty at the ten o’clock lights-out.

I resigned from my cooking job and, having worked for four months on a stretch, asked the Labour Committee for a few days’ rest. We did all we could to make our absence as inconspicuous as possible.

On the evening of 8th June we received the reply.

Every-thing had been arranged, a posse of plain-clothes soldiers would meet us at the appointed place and escort us to a point two miles to the north, where a mounted detachment would be awaiting us with ponies; we should be at their Head-quarters by dawn.

A postscript was added, requesting that we bring a typewriter with us, as the only one the unit possessed had been destroyed in the recent bombing, and a watch and a fountain pen for the correspondent were also required!

There was little more to be done. We went to see McLaren and told him we would be leaving the following night. Although he agreed, he did not seem now to be so enthusiastic about the scheme.

The next morning he asked us to go over to see him again. He wanted us to call it off.

The new Chief of the Japanese Guards, who had only just taken up his position, was an unknown quantity; he appeared to be rather a tough customer. There would doubtless be reprisals.

We had discussed this angle long ago and it had been decided that any consequences visited upon the internees would be more than outweighed by the advantages derived from established connections with a reliable pro-Chungking unit. But since then this change in the Chief of the Guards had been made and McLaren was not now in favour of the scheme.

That afternoon we had a further talk with him. Arthur and I felt that the arrangements had gone too far for us to back out now unless we wished to lose connection with this unit altogether, and in the end Mac eventually admitted that if he were in our position, he would most probably go.

He left it to us to decide, on the understanding that if we did go, then we must arrange with either Wade or de Jaegher to let him know once we had got clear of the wall, so that he would at least be prepared for the rampages of the Chief when he got to hear about it the following morning.

That evening I told my room-mates; they of course had been aware that some such move was in the air. I knew it would put them in an awkward position the next morning when we were found to be missing and it was only fair to give them warning.

Arthur Hummel also told one of his room-mates and it was agreed that if they could get by with-out reporting our absence at roll-call, they would not do so till later in the morning. By eight, Tommy Wade and his scouts were out on the job on the west wall, checking the activities of the guards.

At eight-thirty I pulled on “the Bishop’s Jaegers” and a black Chinese jacket, and joined Arthur in the vicinity of the wall.

The guard was changed but he did not leave his post for the customary walk around. We waited anxiously — eventually he strolled away, but there were two people sitting outside their room directly facing the spot from which we intended to leave.

By the time they were out of the way, the scouts had lost track of the guard! We decided to take a chance. In a moment we were up in the tower and had let ourselves carefully down the wall till our feet touched a pile of conveniently placed bricks.

Tommy Wade followed with a small stool.

From the stool I stepped inadvertently on to Tommy’s bald head instead of his shoulder, and with a hand on the post of the electrified fence, vaulted over. Arthur followed and our knapsacks were thrown to us.

We saw Tommy on his way back up the wall and then made a dash for a graveyard some fifty yards away and flung ourselves behind the nearest grave.

A pause to collect our breath, and we made another dash which took us out of range of the searchlights, and, taking our bearings from the camp, we headed directly north over ploughed fields, through wheat crops, stumbling over ditches and sunken roads until we reached the stream that flowed north of the camp.

A pause to collect our breath, and we made another dash which took us out of range of the searchlights, and, taking our bearings from the camp, we headed directly north over ploughed fields, through wheat crops, stumbling over ditches and sunken roads until we reached the stream that flowed north of the camp.

Wading across this, we headed in the direction of the cemetery.

The moon was rising.

In less than half an hour we could make out the dark mass of trees within the cemetery and by the time we reached the walls there was sufficient light from the moon to see quite distinctly.

We followed a path that led directly to the elaborate gateway surmounted by a triple-tiered roof and supported by carved stone pillars thrown into deep relief by the moonlight. It appeared to be deserted.

We scouted round the wall and turning the south corner facing the camp, we saw the glow of a cigarette and a group of figures huddled against the wall in the shadows.

A figure detached itself and approached us; as he drew nearer; we saw he had a pistol directed against us. We stood still, away from the shadow of the wall, in the moonlight.

Approaching, he asked who we were and we replied: “Friends.” He peered closely at our faces and lowering his pistol, called to the others, “Yes! It is they,” whereupon the other four gathered around us, smiling and shaking our hands in an enthusiastic welcome.

One of them unrolled a couple of triangular white cloth banners on which was inscribed in English: “Welcome the British and American representatives! Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

“They invited us to sit down and, producing cigarettes, started to question us, apparently in no hurry to move.

Having discussed our family status, the camp, the war and the high cost of living, one of them suggested that we might as well get along.

Like us, they were all dressed in black, and each carried a cocked German Mauser. One of them went on ahead about fifty yards, three of them kept with us and the fifth followed about fifty yards behind ; we were evidently making for another rendezvous where we were to meet the sixth.

There, we thought, we should no doubt meet the mounted detachment. We walked for three or four miles in a north-easterly direction, skirting some villages and passing through others to the accompaniment of yelping dogs, but this did not seem to worry our guards.

Once or twice, on a signal from the scout ahead, we hid behind a clump of bushes or pancaked in the grass.

Finally we came to a halt outside a small village into which one of the men proceeded. Here there was some delay. We gathered from the conversation that we were to pick up someone here, who from their remarks was “an opium-smoking son of a bitch”.

In about an hour the guide returned and we moved on. Skirting around the village, we climbed an embankment which I recognised as the Weihsien–Chefoo motor road.

From the shadows of a small wayside hovel we were joined by a tall thin man, slow of speech and equally slow of action.

He was immediately greeted by all hands with a string of abuse relating to his mother’s and grandmother’s reproductive organs for producing such a turtle’s egg who would wear a white coat on a night mission.

Little perturbed, he retired to the back of the hut and reappeared with a bicycle and accompanied by an old man with a wheelbarrow.

[further reading]Beleaguered British and Americans: Greetings to all. The dwarf islanders, the brigands and robbers! have upset the order of the world.

My countrymen have experienced their brutality in war and widespread calamity with human sacrifice beyond any comparison in human history. Without taking account of virtue and measuring their strength, they dared to make enemies of your countries so that you have met with great misfortune and have been robbed of your livelihood and happiness.

We can well imagine that your life in Hades must reach the limits of inhuman cruelty.

As I write this I tear out my hair by the roots.

But the Allies in the Pacific, in south-east Asia and on the mainland of China have counter-attacked with great success. I beg of you to let your spirits rise.

My division is able to rescue you, snatching you from the tiger’s mouth, but the territory we control is small and restricted and I cannot guarantee your safety for a long period.

If you will request your consuls to send planes to pick you up and take you to the rear after I have released you, then my divisions can certainly save you.

Regarding this matter I am asking Mr. Chen to find some way of getting in touch with you and to make arrangements. I respectfully hope that you will be able to carry out these plans and send you all my good wishes.

This serves to inform you that first of all I have to introduce myself to you. I was first-class interpreter in the Chinese Labour Corp, B.E.F., during the last War. . . .

I have been in Ch’angyi just a couple of months and the first thing I decided with the Commander and the Assistant Commander is to arrange to save you all out from the camp and then send you back to your own country.

But please note that from here to Chungking is rather difficult to go right through as the Jap soldiers are all blocked up the ways. So we have to arrange to send you all back by air. In this connection, we have to send a few special men (and I myself) to Chungking to connect the matter and request the Chinese Central Government, American and British ConsulateGenerals to arrange to send down some big aeroplanes for the transportation, so therefore before we save you all from the camp we have a lot of things to do such as to build the aerodrome for the planes to land and etc.

However, after everything settled up we will let you know beforehand.

Kindly believe us that we are easily to save you all out as we have over 60,000 soldiers staying in Ch’angyi area . . . wishing you all have good luck.

Please keep patient for the time being. We may not act till the kaoliang crops grow up.

Wait! Wait! I remain, Yours very truly, S. W. Chen

P.S.—God will help us.

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/Tipton/text/00-Contents.htm

#