- by David Michell

[Excerpt] ...

[...]

The whole plan [the Chinese guerrilas] appeared to be the wild vision of an erratic leader who saw in this bold stroke his hopes for greater recognition.

The whole plan [the Chinese guerrilas] appeared to be the wild vision of an erratic leader who saw in this bold stroke his hopes for greater recognition.

The impracticality, considering the many dangers and the condition of the sick and elderly, not to mention the high percentage of women and children, was evident to the committee.

They [the committee] responded cautiously, not wanting to lose the link with a potentially valuable ally, but at the same time not wanting to give the green light to a far-fetched scheme which they might be powerless to stop once it was launched.

The camp committee took Tipton and de Jaegher into their confidence to get their advice.

The outcome of these discussions was that the two of them should try to escape from the camp so that they could meet the leader of this unit, who purportedly had an army of 60,000 soldiers.

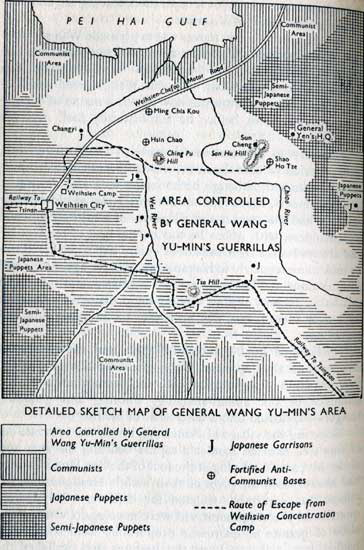

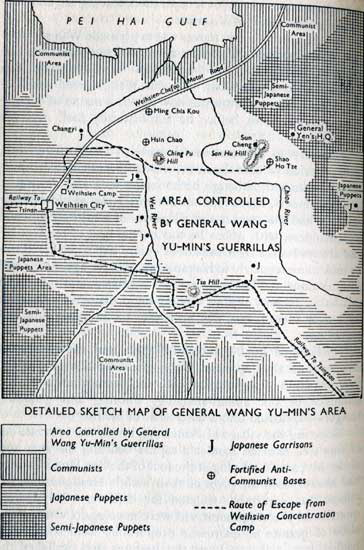

De Jaegher worked through his cesspool coolie cohorts to acquire a good knowledge of the location and size of the military groupings in Shantung Province, and he and Tipton mapped out a course of action.

To ensure the success of their escape, a number of things had to all work together. The guards, the moon, the place and time for rendezvous all had to be carefully considered, and there was no time to lose.

June 9th or 10th, just ten days away, was chosen as the target date, as that night would give them an hour of darkness to make good their escape from the camp area before the moon’s ascent.

It was necessary, too, to make the escape attempt during the duty period of the team of guards that were the most lax. This squad was on the 9:00 p.m. watch, and their routine began with an inspection up and down their beat by the wall and in their tower, followed by a ten-minute break for ocha (Japanese tea) and a smoke.

In that short span of time, de Jaegher and Tipton concluded, they would have to make their escape.

Only three members of the camp committee knew the date the escape would be attempted, and all were sworn to secrecy. They agreed that de Jaegher should be allowed to tell his Superior, Father Rutherford, now that plans were definite and their escape kits were being prepared. Little knapsacks were packed with a few personal effects, plus a typewriter, a watch and fountain pen requested by the Nationalist soldiers.

Right at the last, Rutherford persuaded de Jaegher to back out of the venture because he feared there could be cruel reprisals on the rest of the camp, and he didn’t want one of his priests being responsible for it.

With great reluctance de Jaegher agreed.

The organizing group of Tipton, de Jaegher, Roy Tchou, and Tommy Wade asked Arthur Hummel, Jr., an American who had been a teacher in a school in Peking, to take his place. Hummel accepted without hesitation, and final preparations were given fine-tuning.

News had come through the “water-closet wireless” that a small band of Chinese soldiers disguised as peasants would be at the meeting place, two miles north of the camp, at the prearranged time. Every care was taken not to arouse any suspicion within the camp and, apart from accelerating their suntanning program, Hummel and Tipton carried on as normally as they could.

The suspense for those in the know for the last few days was intense.

The watchtower chosen for the escape bid was the shortest one of the six around the walls. It was located in the middle of the west side, where a bend in the wall to the north obscured it from the searchlight tower beams.

On June the 8th, Hummel and Tipton and the other three, including de Jaegher, did a dry run during the daytime. They got a good look at how to avoid touching the electrified wire while scaling the wall at the tower.

The next evening, while everyone else in camp was going about their humdrum routine in what, for many, had become an almost zombie-like existence, the scent of freedom was already in Hummel’s and Tipton’s nostrils, and their hearts were beginning to beat faster. As casually as they could, they let someone in their respective rooms into the secret, asking them to do their best to cover for them, at least until the evening roll call, by which time they would hope to be safely at the Nationalist soldiers’ headquarters.

By 8:00 p.m., as Hummel and Tipton slipped into their close-fitting black Chinese clothes that had been specially made and smuggled in to them, the others were closely monitoring the movements of the guards.

At 9:00 p.m., the easygoing watch came on duty as expected.

To Hummel’s and Tipton’s consternation, however, the tower guard didn’t walk his beat straightaway as he usually did. The two would-be escapees waited breathlessly in the shadows for ten more minutes and then breathed a sigh of relief as the guard moved away from the tower.

In a flash, de Jaegher, Roy Tchou, and Tommy Wade ran into the tower and helped Tipton and then Hummel up the wall and over the live and barbed wire fences.

Once on the other side, the duo retrieved the knapsacks that had been thrown over after them and ran to the overgrown Chinese graveyard some 100 feet away, throwing themselves down behind the first grave mound they came to.

As they waited a few moments to catch their breath and get their bearings, they realized with much thankfulness that no alarm had been raised.

They got up noiselessly and, after stumbling through the fields of millet, cautiously waded through the river that ran north of the camp.

With the moon now shining, they headed off quickly for the rendezvous a mile and a half away.

Great was their relief on reaching the cemetery to find a mounted detachment in hiding, waiting with ponies to take them to their headquarters’ hideout. Striking up friendly conversation with the soldiers, they traveled with them through the night, eventually reaching the unit base the following afternoon.

Meanwhile, back at the camp, de Jaegher and the others climbed down out of the tower undetected and then endeavored to retire casually for the night.

De Jaegher’s first concern on reaching his room was to pray for his compatriots’ safety.

At the next morning’s roll call, Hummel and Tipton were not missed, but knowing their absence couldn’t be concealed for very long, Ted McLaren, the chief of the Camp Committee, reported to the Japanese that they were missing.

The commandant raged and fumed.

Roll call was doubled to morning and evening, and food supplies took a further cut back — no meat, not even horsemeat for a while. But all of us were thankful that the Japanese response took the form of voluble haranguing rather than any physical punishment.

Eventually, however, the furor over the escape of the two men, who had achieved hero status in camp, died down completely. Nothing new seemed to happen to relieve the daily tedium.

When some months passed with no news of Hummel and Tipton’s whereabouts or of the war’s progress, de Jaegher and his colleagues began to wonder if a worse fate had met their friends.

One day, however, as de Jaegher mumbled the agreedon password wushi-liu while shuffling among the Chinese coolie work party, he got a nod of acknowledgment.

“Come to my ‘office’ (a modified latrine cubicle) so we can discuss the next job,” de Jaegher called out with annoyance as he looked at this man. With the guard’s suspicions satisfactorily allayed, the priest escorted the coolie into the cubicle.

Once inside, the workman pulled out a tightly compressed note from the lining of his baggy trousers and, faintly smiling, handed it over to de Jaegher.

That night, when de Jaegher had decoded the message, he was hardly able to contain his excitement.

At long last, proof had come that Hummel and Tipton had made it safely to freedom and that two-way communication was about to start.

He let McLaren and Hubbard of the Camp Committee into the secret. A brief coded response was sent out in the same manner as it had come.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/aBoysWar/ABoysWar(LaTotale)-pages.pdf

#