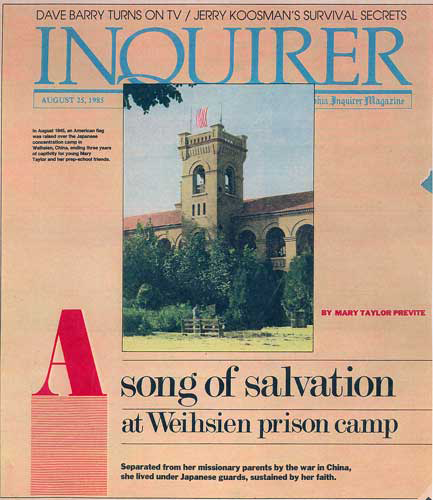

- by Mary Previte, née Taylor

[Excerpt]

...

WE LISTENED WIDE-EYED TO THE whisper that passed from mouth to mouth one day at roll call: “Hummel and Tipton have escaped!”

WE LISTENED WIDE-EYED TO THE whisper that passed from mouth to mouth one day at roll call: “Hummel and Tipton have escaped!”

My heart pounded against my ribs as I grabbed Podgey Edwards and started jumping up and down. I tried to recall what Hummel and Tipton looked like. Shaved bald and tanned brown like Chinese, someone said. Chinese clothes. But how in the world, I wondered, did they get over the electrified wire atop the camp wall without getting killed?

Our teachers and the older boys were more subdued. Escape would mean instant reprisals.

Roll call that day dragged on and on. With Hummel and Tipton missing, the guards’ count failed to tally, and when the Japanese realized what was wrong the commandant unleashed the police dogs. And Japanese soldiers promptly arrested the nine remaining roommates from the bachelor dormitory and locked them up in the church for days of ugly interrogation. But nothing worked. Hummel and Tipton were gone.

Roll call was never the same after that. Instead of one, we now had two roll calls a day. Japanese guards cursed and shouted. They counted and recounted us each time. They also dug a monstrous trench beyond the wall, 10 feet deep and five feet wide, and beyond that they strung a tangle of electrified wire. No one would ever escape again.

Laurance Tipton had been an executive with a British tobacco importing firm. Arthur Hummel Jr. had been a professor of English at Peking’s Catholic University; today, he is the U.S. ambassador to China.

Not until years later did I learn the story of their escape. Shortly after the nightly changing of the guards, in a prearranged plan with Chinese guerrillas, they had gone over the wall at a guard tower. For the rest of the war, maneuvering in the hills within 50 miles of Weihsien, they employed Chinese coolies - either repairmen or “honey-pot men” who carried out the nightsoil from our latrines and cesspools - to smuggle coded messages in and out of the camp.

This was our “bamboo radio,” known only to the camp’s inner circle. It was a deathly dangerous business. The Japanese had once found a concealed letter on a Chinese coolie as they were checking him before entrance into the camp; they dragged him into the guardhouse and beat him until he was unconscious. He was never seen again. Another Chinese confederate who was passing black-market supplies over the wall to hungry prisoners slipped, in his hurry to get away as the guards approached, and was electrocuted on the wire that crisscrossed the wall. The Japanese left his body hanging there for most of the day, as a grim warning.

News from the “bamboo radio” was delivered, therefore, with extreme care. A message would be written on the sheerest silk, wadded into a pellet, placed inside a contraceptive rubber and then stuffed up the nose or inside the mouth of a Chinese workman. Once inside the camp, at a prearranged spot, the coolie would clear his sinuses and spit out the news. Insiders then pounced on the spit wad and took it to the translator.

Ironically, the Japanese themselves helped confirm the accuracy of some of the smuggled information. They distributed English editions of the Peking Chronicle, a carefully doctored propaganda rag filled with hideous lists of sunken Allied ships and downed American planes. In our Current Events class, we followed the names of the places where battles were in progress: the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, Guadalcanal, Kwajalein, Guam, Manila, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. It was obvious where the battles were raging: closer and closer to Japan! Our bamboo radio was right. Japan was on the run.

[further reading]http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/Mprevite/inquirer/MPrevite.htm

#