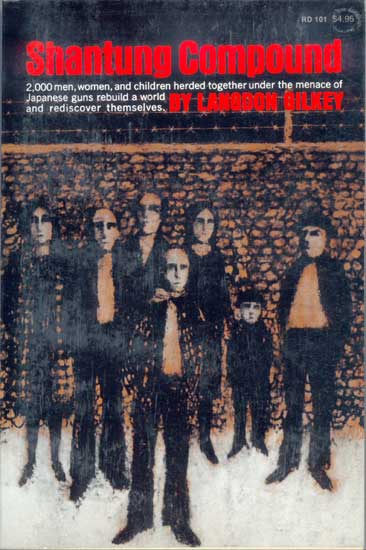

- by Langdon Gilkey

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

Everyone expected the end of our world to come; yet, for the moment, we were still absorbed in the trivia of camp life.

Everyone expected the end of our world to come; yet, for the moment, we were still absorbed in the trivia of camp life.

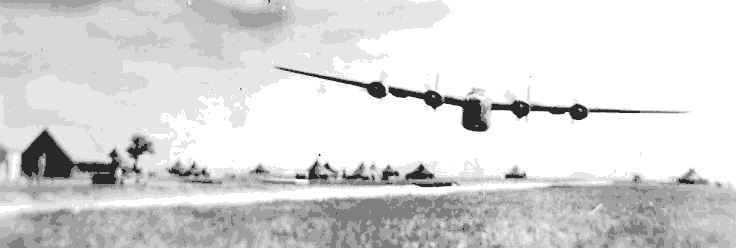

Then on Friday, the end came in as glorious a Parousia as the wildest biblical scenarist could have devised. The day, August 17, 1945, was clear, blue, and warm, as such a day should have been. We all began our chores of cooking, stoking, and cleaning up slops as usual. About the middle of the morning, however, word flashed around camp that an Allied plane had been sighted.

Two or three times during the course of the war, we had seen one of “our” planes flying way up in the upper atmosphere, a fast-moving silver speck far out of identification range.

We felt sure they were Allied because of their solitary height and their speed, a vivid contrast to the antiquated Japanese planes that chugged overhead, burning, as one wag put it, “coal balls.” Those lonely high fliers sent an electric shock through the camp on those two or three occasions, for they were, from the beginning of the war to its end, our only contact with Allied military might. Yet at that distant height they seemed, like Aristotle’s god, to be wholly indifferent to our presence in their world, indeed, if they knew about our existence at all.

The plane that had been sighted on that Friday was evidently quite different—or so the boy who spread the word made clear as he ran through the kitchen yard screaming in an almost insane excitement,

“An American plane, and headed straight for us!”

We all flung our stirring paddles down beside the cauldrons; left the carrots unchopped on the tables, and tore after the boy to the ball field. This miracle was true: there it was, now as big as a gull and heading for us from the western mountains.

As it came steadily nearer, the elation of the assembled camp-1,500 strong—mounted.

This meant that the Allies were probing into our area, not a slow thousand miles away! And people began to shout to themselves, to everyone around them, to the heavens above, their exhilaration: “Why, it’s a big plane, with four engines! It’s coming straight for the camp—and look how low it is! Look, there’s the American flag painted on the side!

Why, it’s almost touching the trees! . . . It’s turning around again. . . . It’s coming back over the camp! . . . Look, look, they’re waving at us!

They know who we are. They have come to get us!”

At this point, the excitement was too great for any of us to contain. It surged up within us, a flood of joyful feeling, sweeping aside all our restraints and making us its captives.

Suddenly I realized that for some seconds I had been running around in circles, waving my hands in the air and shouting at the top of my lungs. On becoming aware of these antics, I looked around briefly to see how others were behaving. It was pandemonium, the more so because everyone like myself was looking up and shouting at the plane, and was unconscious of what he or anyone else was doing.

Staid folk were embracing others to whom they had barely spoken for two years; proper middle-aged Englishmen and women were cheering or swearing. Others were laughing hysterically, or crying like babies.

All were moved to an ecstasy of feeling that carried them quite out of their normal selves as the great plane banked over and circled the camp three times.

This plane was our plane. It was sent here for us, to tell us the war was over. It was that personal touch, the assurance that we were again included in the wider world of men—that our personal histories would resume—which gave those moments their supreme meaning and their violent emotion.

Then suddenly, all this sound stopped dead.

A sharp gasp went up as fifteen hundred people stared in stark wonder. I could feel the drop of my own jaw. After flying very low back and forth about a half mile from the camp, the plane’s underside suddenly opened.

Out of it, wonder of wonders, floated seven men in parachutes! This was the height of the incredible!

Not only were they coming here some day, they were here today, in our midst!

Rescue was here! For an instant this realization sank in silently, as a bomb might sink into water. Then the explosion occurred. Every last one of us started as with one mind toward the gate. Without pausing even a second to consider the danger involved, we poured like some gushing human torrent down the short road.

This avalanche hit the great front gate, burst it open, and streamed past the guards standing at bewildered and indecisive attention. As I rushed by, I caught a glimpse of one guard bringing his automatic rifle sharply into shooting position. But his bewilderment won out; he slowly lowered his gun.

It was the first of several lucky breaks that day, when split-second decisions had to be made in the face of absolutely new situations to which no page of the Japanese soldier’s manual applied.

By some quirk of Providence, as in this instance, the decision was the right one. Oblivious to all this danger, yelling and shouting, jostling and pushing, we rushed through the narrow streets of the neighboring village and out into the fields. So intent were we on finding our parachuted rescuers that we scarcely had any time to savor the sweet feeling of freedom that colored so vividly those earliest moments.

Suddenly we had become part of the wider world; even the Chinese village of eight clay huts huddled near the walls of the camp held mystery and fascination for us; its rude dirt street was beautiful. Every sight, every smell, every sound was etched on our consciousness. These sensations of freedom were like a tonic, building up our excitement to an ever-higher pitch.

[excerpt]

About a half mile farther on, we came to a field high with Chinese corn.

My first sight of an American soldier in World War II was that of a handsome major of about twenty-seven years, standing on a grave mound in the center of that cornfield.

Looking further, I saw internees dancing wildly about what appeared to be six more godlike figures: how immense, how strong, how striking, how alive these American paratroopers looked in comparison to our shrunken shanks and drawn faces! Above all, their faces were new!

After two and one-half years, we had come to assume subconsciously that everyone in the world looked like the fifteen hundred of us—we were our world. I had forgotten that more variety than our camp features provided was possible.

Meanwhile, some of the more rational internees were trying to fold up the parachutes.

Most of us, however, were far too “high” for the task. We just stood there adoring, or ran about shouting and dancing.

Our seven heroes were concerned with other matters.

They had descended into the fields with their automatic weapons at the ready, anticipating a Japanese attack at every moment. The last thing they expected to find was this onslaught of ecstatic internees whose dancing about was making it impossible for them to deploy safely in the gao-liang field as they had planned.

In any case, after gathering up their gear and talking to enough of us to get an idea of the situation, they asked to be guided to the camp—so they “could take charge there.”

This casual, matter-of-fact statement of intentions sent us into another transport of rapture.

The Japanese would no longer rule us!

With this word, our cup of ecstasy ran over. The internees picked up their discomfited rescuers on their shoulders, and in a wild cheering procession reminiscent of a victorious high school student body bringing home the winning coach and team, the internees wound their way back to the camp.

As we approached the camp, the effect with its contrapuntal motifs was a mad confusion. Below there were the joyous, abandoned internees singing and yelling like Maenads in a bacchanalia, conscious only that the Lords had come and wishing only to shout hosanna. Above, on their shoulders, were the grim, watchful American soldiers, their arms at the ready, alert for any hostile move on the part of the twenty gaping Japanese guards who stood by the gate as we approached.

This time the tension was even more marked.

The guards had to decide whether to fire on the seven parachutists or not.

At point-blank range, they eyed one another for a brief moment. Then, as the triumphal procession, unmindful of the military drama being enacted above their heads, proceeded to the gates, a Japanese guard saluted—and the gates were opened.

We first grasped the military aspect of the capture of the camp when the procession came to a halt just inside the gate. At that point, the young major in charge leaped to the ground and asked,

“Where’s the chief military officer of the camp?”

Somewhat awed, the internees nearest to him pointed to the neighboring yard where the Japanese administrative officers were.

With a fine sense of drama, the major, who had a service pistol on each hip, drew them both, checked them out carefully, and then strode toward the head office.

In his figure, every internee saw the embodiment of the righteous marshal striding fearlessly through the swinging doors into the barroom where a hated outlaw awaited him.

The scene that ensued was in the same great tradition—so we were told afterward by the major’s interpreter. With both guns levelled, the major entered the room. There sat the Japanese officer, his hands spread out on his desk, awaiting his antagonist.

Neither knew what the other intended to do, nor just what he himself would do in response—again it was touch and go.

Through his interpreter, the major demanded that the Japanese officer hand over his gun and recognize that the American army was now in full charge.

This must have been a hard decision for the chief officer. Probably the Japanese had been taken so unaware by the parachuting a bare twenty minutes earlier that they had had no chance to communicate with their superiors in Tsingtao.

Moreover, the chief himself probably had no accurate information as to whether Japan had really surrendered or not. If it was true, then to fight these seven men and possibly to kill them, would make it go all the harder for the chief and his men. But if Japan had not yet given up, then to surrender his well-armed force of fifty men to seven paratroopers would have been an act of cowardice and reason to commit hara-kiri.

For a full moment the commandant considered.

Then slowly he reached into the drawer in front of him, as the major’s trigger finger twitched.

With a deliberate motion, the chief brought out his samurai sword and his gun, and solemnly handed them over to the major, who was astounded, relieved, and somewhat touched.

At that remarkable gesture, the major handed back these symbols of authority, told the chief that they would work together, and stalked from the room.

With that confrontation, the camp passed into American hands; henceforth, Japanese soldiers and G.I.’s alike took orders from the American officers.

etc., etc.

[further reading] ...http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/BOOK/Gilkey-BOOK(WEB).pdf

#