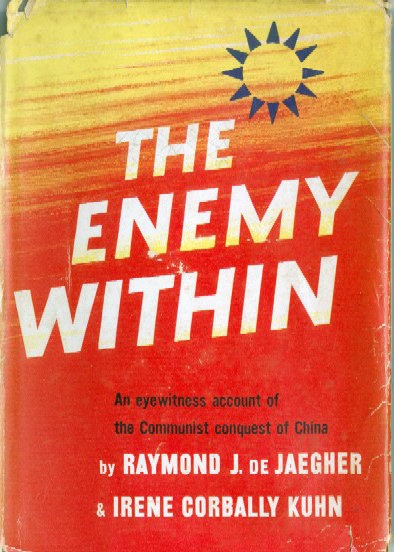

- by Raymond deJaegher

[Excerpt] ...

[...]

When Mr. Mac Laren read my translation to the camp’s administrative committee, they all listened with something less than wild enthusiasm.

When Mr. Mac Laren read my translation to the camp’s administrative committee, they all listened with something less than wild enthusiasm.

The letter constituted a minor problem, really. The committee quite naturally didn’t want to risk offending the Communists, who were all around us, nor did they want to stage any kind of revolt. If the revolt was unsuccessful, everyone in camp would suffer, and if the revolt and the Communist attack succeeded and we were evacuated to Yenan, we would be even worse off. Finally, after a great deal of thoughtful discussion, the committee concocted a letter which thanked the Communists for their thoughtfulness and kindness, and explained that since only three hundred of the seventeen hundred internees would be able to make the march, we felt it best to stay where we were. We added that we had learned that the war was going so well that we were sure we would all be liberated soon, and therefore it seemed best to wait. We sent the letter out by the same coolie who had brought the Communist missive in, and I was ahead of the game, for this was one coolie to whom I gave a wide berth when I sent out the camp’s messages to the Nationalist guerrillas.

I had the feeling that this message from the Communists meant that the end was nearer than any of us believed, and on the eleventh of August word came from Tipton and Hummel that the Japanese were on the verge of giving up, and advising us that we must prepare ourselves. They inquired, too, if we thought it a good idea for the Nationalists to take over immediately. We replied at once to this heartening message that we had decided to wait for the Americans to release us, since the end was so near.

And it didn’t take the Americans long to get to us. Less than twenty-four hours after the Japanese surrender we heard of it in the most glorious and spectacular way possible. There was a vibrancy in the air on the fourteenth. Everybody sensed something big had happened, but we were afraid to speak our thoughts, afraid to mention the word “victory.” The tension and excitement mounted through the day and night, and on the morning of the fifteenth we knew the dejection in the Japanese officers’ attitude could mean only one thing, that the war was over and they had lost it.

And suddenly in the sky, a fine clear blue summer sky, over the camp there appeared a big American bombing plane, a B-24. It flew low enough for us to see painted on its side the words “Flying Angel,” and never, we thought, was anything so aptly named. All the internees began to sing, “God Bless America.” The plane circled and flew around us a few times, and the whole camp poured out onto the grounds, shouting, singing, waving. The Flying Angel disappeared to gain altitude and presently came back, and we counted our saviours literally dropping out of the skies. When the parachutes opened, the camp cheered and stamped and roared and hoorayed and went wild with joy. People cried and laughed and hugged and kissed each other and slapped one another on the back, and then the camp moved en masse to the main gate to greet the American fliers.

The Jap guards were still on duty, but they made little if any effort to stop men, and women, us and children streamed out through the gates, tasting freedom for the first time in two and a half years.

The paratroopers had come down in the sorghum fields and, since the grain was very high, we had to go in and find them and guide them out. The joyful shouting and calls of “Where are you?” and “Here, right over here!” went on until we had collected the team of which a young American major named Stanley Staiger was in charge. He had arms for the camp in case the Japanese proved difficult, but we assured him we didn’t need them. The fight was out of the Japs here in Weihsien.

Major Staiger was hoisted to the shoulders of a few of the strongest men, and that was the way he entered the camp. On all sides the Japs were saluting him and bowing in deference. The young major returned their salutes with military punctiliousness from the shoulders of the men who such a little time before had been the Japs’ despised enemy inferiors. They were now free men again, superior in their victory but with commendable restraint and sportsmanship, not showing it or taking advantage of it, except to see that authority was shifted at once to them from their erstwhile captors.

As the major waited for the Japanese officers to assemble, an old woman ran up and kissed his hand. He blushed a fiery red, but he suffered her expression of gratitude rather than snatch his hand away and hurt her. He almost ran into the office while the Japanese guards bowed low. The Japanese commandant put his sword on the table. Major Staiger accepted his surrender. Now we were free, actually and technically free, and a great shout went up, cheers for the United States, cries of “God save the King!” from the Britons, cheers for all the Allies. All the anthems of the countries represented in that camp were sung by their citizens, and the August air was a bedlam of joyous sound.

Meanwhile, Major Staiger and the commandant discussed the business of the day and how the camp could be taken over by the victors. It was thrilling to see this handful of young paratroopers, competent, efficient, and pleasant, take up their stations. They were so full of vitality that they actually communicated some of their zest and exuberance to our bedraggled and debilitated numbers.

Next day more planes came over, and later B-29s from the Okinawa air base dropped supplies by parachute. On the heels of the supplies from Okinawa came Colonel Hyman Weinberg from a China base, and he superintended the evacuation of the camp by rail and air, a job that took two months. I was one of the last to leave, flying out in October 1945 to Peiping.

[further reading] ...http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/rdjaegher/text/ChapterXVIII.htm

#