Chapter Twelve

"Comes now the last step. It is March, 1943. About noon of the 14th a messenger from good Dr. Hoeppli of the Swiss Consulate comes with the fateful word. We are to be taken to internment camp in a neighboring province. We have ten days in which to dispose of our personal and household effects, packing what we think we will need for an indefinite stay in Weihsien."

Frances told the author later that the Scripture passage that meant most to them in the camp was Habakkuk chapter three:

For though the fig tree shall not blossom, neither shall fruit be in the vines; the labor of the olive shall fail, and the fields shall yield no food; the flock shall be cut off from the fold and there shall be no herd in the stalls. Yet will I rejoice in the Lord. I will joy in the God of my salvation. Jehovah the Lord is my strength and He maketh my feet like hinds' feet and helpeth me to keep my looting on the heights... .

"That is where," she said, "in an internment camp you have to walk ― on the heights and not be dragged down."

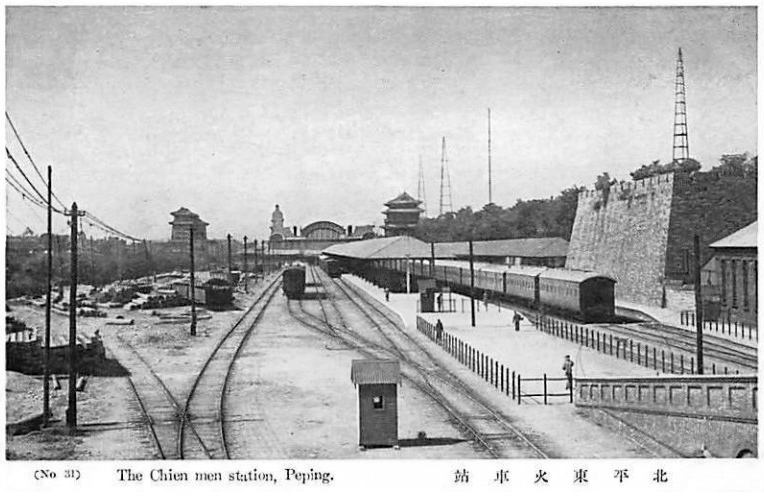

Fred's account continues: "Toward sundown we are herded out on to Legation Street and headed for The Chienmen Station, a sight for gods and men, smaller bags on backs, larger articles on 'sammies' (two rough poles mounted on a small wheel) or trucks improvised from roller skates. Hundreds line the sidewalks to view the humiliation of the 'enemy nationals.' Now we know what it means to be 'made a spectacle unto the world ... to be as the filth of the world and the offscouring of all things.' We know what it is to taste the savor of being 'alien enemies' and feel no rancor. There is even a kind of fierce joy at the chance to pay some of the arrears due to un-Christian attitudes in our national life.

"Three-thirty in mid-afternoon finds us at the platform at Weihsien, thirsty and dishevelled, surveying an uninviting prospect. Trucks receive the men and baggage, buses the women and children. Past the ancient defences of Weihsien city, on beyond the grey walls of the Presbyterian Mission. The gates close upon us, and we are prisoners in the forlorn 'Castle of Despair."'

Frances remembered that one of the things that bothered her a great deal as she thought about being imprisoned was that she could no longer be with her Chinese friends to do Christian work. But then she realized that a missionary could never be separated from her job; rather, she found herself in an amazing new field of European commercial people who had very little, if any, religion. Later, she learned that in other camps where there were no missionaries, these "respectable people" when left without any spiritual help, fell apart as far as morale and morals were concerned.

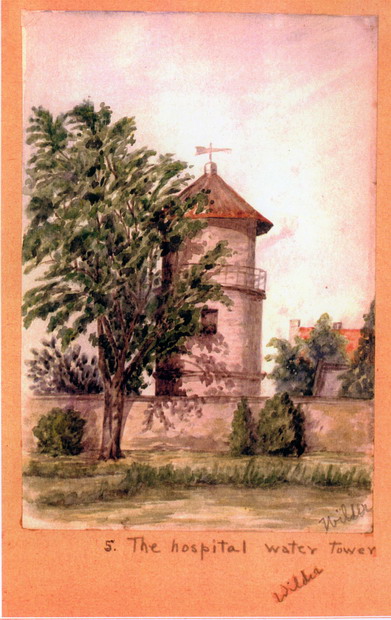

Arriving at Weihsien, Fred described what they saw: "Bare walls, bare floors, dim electric lights, no running water, primitive latrines, open cesspools, a crude bakery, two houses with showers, three huge public kitchens, a desecrated church and a dismantled hospital, a few sheds for shops, rows of cell-like rooms, and three high dormitories for persons who are single ― out of this we set to work to organize a corporate life."

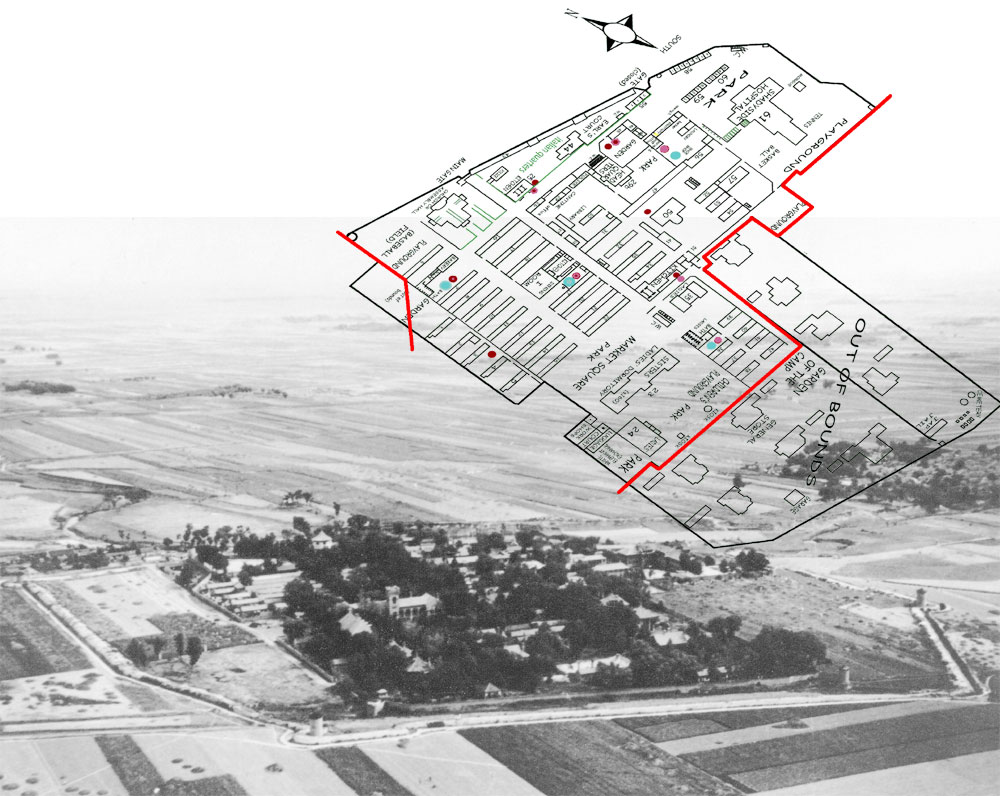

Frances' description of the camp supplements Fred's: "The Presbyterians had two mission compounds that they were particularly proud of, one was a big college on the Bosphorous, and the other was at Weihsien in the Province of Shantung. This compound which covered several city blocks was a wonderful example of mission strategy and Christian foresight. Inside the outside walls were several smaller compounds, each with its own walls. One was for the hospital, the Nurses' Training School and the doctors' residences, one for the Bible Women's Training School and the dormitory for the Bible women, another for the Middle Schools. There were elementary schools as well with their dormitories, row upon row of them. It was ideal for a prison camp.

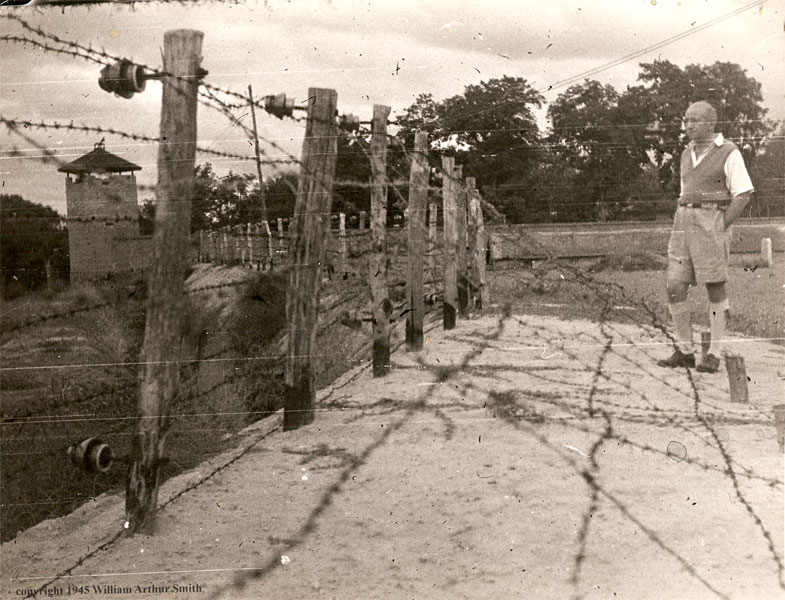

"Although we were in a civilian internment camp and thus not subjected to such severe conditions as prisoners of war, we had to get used to lack of food (about 1,000 calories a day), lack of sanitation, overcrowding and vermin of all kinds. These, things, however, were nothing compared to the loss of our freedom, the anguished feelings of being completely at the mercy of the guards. Moreover, no matter in what direction we directed our gaze; it was met with a ten-foot brick wall with electrified barbed wire on the top. On the outside was a further entanglement of electrified barbed wire, beyond which was a moat and another entanglement of barbed wire."

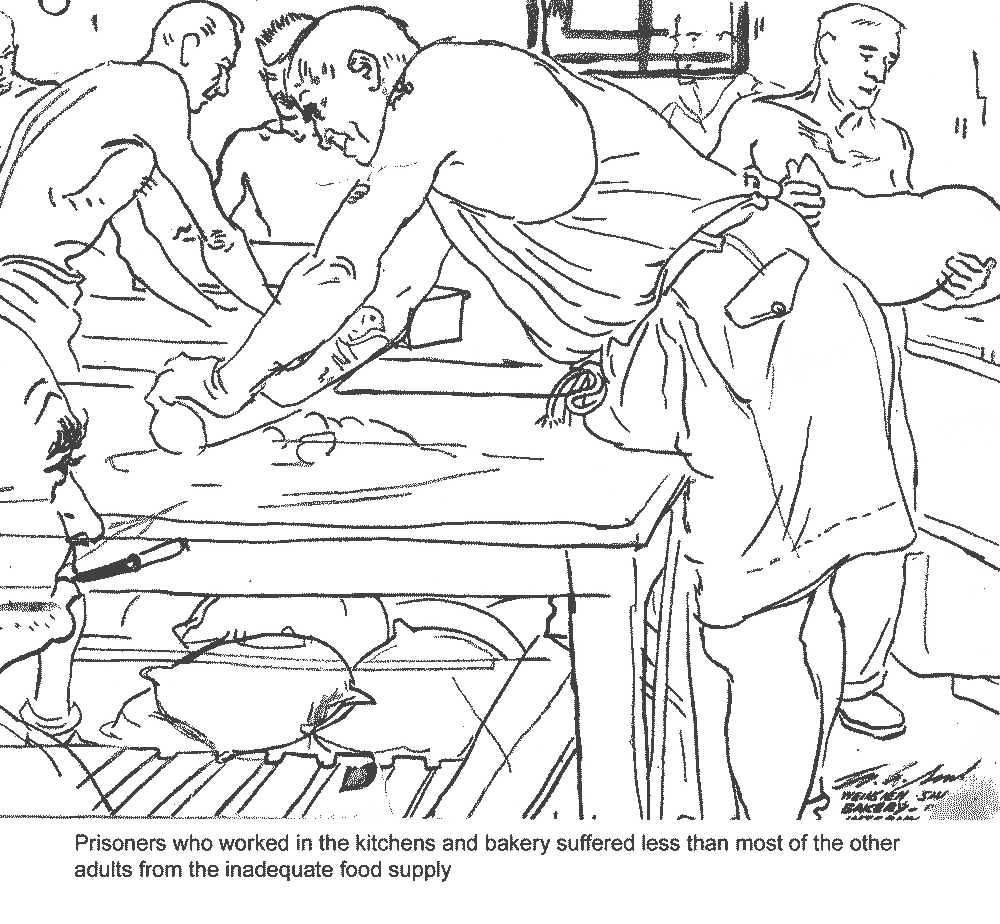

Fred's account continues: "The next few days are a confused recollection of unpalatable food and toiling over mountains of baggage. Rain falls and transforms the dust into a quagmire. A keen wind from the north springs up and searches our bones. We lift heavy crates, boxes and trunks with a last-ditch energy that accomplishes surprising results. Other trainloads of refugees arrive every two or three days until we number eighteen hundred souls: British, American, Greek, Belgian, Philippino, Indian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Russian, Chinese, Scandinavian, Parsee, Iranian and Palestinian. There was also one Panamanian. At first volunteers staffed the kitchens, bakery, repair shops, pumps and bathhouses. Dr. Loucks and Miss Whiteside with helpers started whipping the hospital into shape."

Frances reported that in camp Fred first volunteered for the meanest jobs, such as cleaning the toilets and showers. Later he became coordinator of the wells which meant that he was responsible for getting pumpers to man the pump-handles at all times. Then he worked in the carpentry shop.

"At mealtime we found yellow slips on the long pine tables in the kitchens asking each to indicate experience and preference regarding various kinds of camp labor. There was work for all and those who refused were few. The Yenching University contingent of teachers, doctors of literature, philosophy and science worked beyond their strength. The Catholic fathers and sisters won golden opinions by their cheerful assumption of disagreed tusks. Frank Connelly of the Baptist Mission managed a kitchen for eight hundred people. He was a born leader and people of all sorts worked with him gladly.

"Next we found white slips at our places indicating procedure for electing camp committees. When the Japanese imprisoned us, they imprisoned democracy, democracy ― that was the watch word. Yet they seemed pleased to have the details of camp management left to the prisoners, while they laid down general rules. These were: no traffic with the enemy, no black market, no effort to escape, no vandalism, no insubordination.

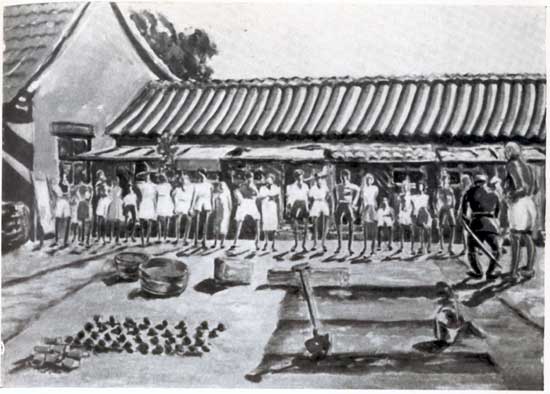

"Management functioned through nine committees: Supplies, Quarters, Employment, Engineering, Discipline, Medical, Education, General Affairs and Finance. We were fortunate to possess men of strength and experience among our number who could represent our interest forcefully. The Japanese were supercilious and overbearing, but not cruel, to the Westerners. They were determined to put us in our place, but after a few cases of slapping and punching, they conceded the right to enforce discipline to our own elected officers. Police numbers to wear, daily roll call, occasional parades, and searches, as well as insufficient rations reminded us that we were prisoners. Public enemy number one was monotony. Latrines, cesspools, ash heaps, garbage bins and broken masonry greeted one on every hand. Dreary surroundings and depressing work heightened the deadening monotony."

Frances remembered that food, or more properly the lack of it, was the chief preoccupation of the internees. The main staple of the prison diet was an inferior flour which often seemed to include the leavings swept up off the mill floor. (Rice was a luxury in grain-producing North China, only to be enjoyed by the inhabitants on festival occasions.) A kind of bread was made from this flour and the ration per person was six small slices a day. For breakfast the bread was soaked in water and made into an insipid bread porridge.

Sweet potatoes were issued only once in the two and a half years. They were put in a huge cauldron and stirred so they would not burn on the bottom. Since no proper cooking implements were issued, the cooks went scrounging around the compound looking for something with which to stir this treat. The Presbyterian Mission at Weihsien was where Henry Luce, the magazine magnate, had lived as a boy with his missionary parents. One day they found a baseball bat which they were "sure" had belonged to Henry Luce. With that baseball bat they stirred the sweet potatoes which were so very special because they were sweet.

One of the worst irritations was having to line up for roll call twice a day in all kinds of weather. Everyone had to wear his camp number and be counted off by the Japanese guards. At times an inmate would forget his or her number and a first offence was usually overlooked, but the consequences could be unpleasant if it happened again. Frances forgot her badge once and had no difficulty, but then she forgot it a second time and wondered what would happen. She remembers that at that point, Fred leaned over and pinned his number to her blouse, thus assuming the blame himself.

Then the lack of sanitation was a severe problem, especially the cesspools. They were open pits located near the living quarters. The toilets also were just holes in the floor in sheds, and it took special grace to clean them. Some of the prisoners would bribe anyone they could to do it for them. A little boy who had lived most of his life in the camp, seeing the beautiful harbor at Tsingtao after the war, said to his mother, "Oh, Mother, see what a great big cesspool!" He had not known any other body of water!

The difference between survival and disease or starvation was the operation of the black market. Fred Pyke was a very moral person, punctilious about right and wrong, but he worked on the black market chiefly because of 450 children in camp. Their whole lives would have been affected without proper nourishment, and the black market did produce peanuts and eggs. The Chinese would push them through the drain holes at the base of the wall; also little tiny dates, no bigger than a thumb-nail, came through.

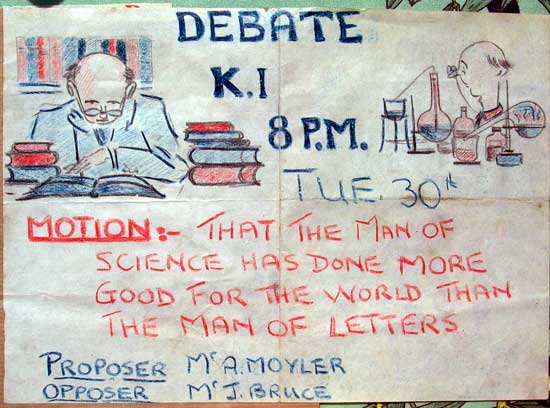

Fred's account continues: "Musical instruments were allowed in camp. There was a Salvation Army Band, and an orchestra was organized. There was also an amateur dramatic society which nobly supplied a play a week. A lecture course was run one night a week, and in addition, Lucy Burtt of Yenching University conducted a course of readings in history, ancient and modern, which was enormously popular.

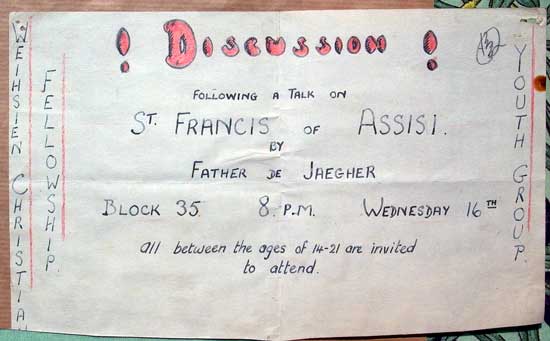

"The greatest morale builder was the collective religious life. An inclusive Christian Fellowship was set up taking in all but the Roman Catholics. In addition the Anglican Church conducted three or four services on Sunday and daily morning and evening prayers. An Evangelistic Band was organized, enrolling over a hundred members, and these conducted a colorful service each Sunday evening. They also had a weekly prayer meeting. Prayer groups supporting this work met all over the camp, some daily, some twice and some once a week."

Fred and Frances organized an early morning intercessory prayer group which proved to be a great learning experience. Frances was acquainted with a charming, musical and cultured high-born Russian woman who asked for prayer for her husband, a Scotsman. He had been used to money, luxury and servants on the outside, but in camp had been shirking on his share of the work. He was letting her carry their water, doing all the washing and other hard work, never lifting a finger to help. She asked the group to pray for her husband, because she was very ashamed of his slackness when everyone else was doing his share of the work. After several weeks of daily prayer for him, Frances one day happened to meet his wife and asked how things were going. She was enthusiastic, recounting how she had become aware a night or two before that her husband was tossing and turning and not sleeping well. In the morning he said to her that he realized he was not behaving in the way he should, that he should be helping her more and doing more of his share of the work of the camp. Then he picked up the buckets and went off to get the water. A few weeks later Frances encountered her friend again, and she said that it was as if she and her husband were on their second honeymoon. Through this experience Frances became more aware than ever of the power of prayer and of the Holy Spirit to change a person's heart.

Another example of answered prayer involved another white Russian lady who was from the opposite end of the social scale, a pathetic case. Her mother, as was the case with so many white Russians, had fled from Russia to China when the Bolsheviks took over. Many had no trade or skill, so some of the women drifted into the pitiful business of prostitution in the port cities of Tientsin and Shanghai. The young woman in question had been born in a brothel, and her lifestyle was a problem in the camp. One day a friend asked the group to pray for her, because she really wanted to be different but did not know how to change. After considerable prayer the girl made a right-about-face and started a new life.

Fred's account continues: "One of the interesting and profitable addresses made in the weekly prayer meeting consisted of finding parallels between the Weihsien Camp and that of the children of Israel in the wilderness. This talk was given a number of times.

"All water in the camp was raised to the surface by hand, gangs of men and school boys keeping the flow running fourteen hours a day. Because of fire hazards and the needs of the public kitchens, the supply of water had to be kept going at all times. After the arrival of our rescue team, when the manpower was diverted to the salvaging of supplies brought in by plane, Frances organized a crew of women who kept the water flowing so that meals were on time.

"Gradually, others came and we were put under the command of Col. Hyman Weinberg, a capable officer, who enjoyed the respect of all. A recreation officer, Captain Ashwood, with daily lectures broadcast through the camp, and a library stocked with home magazines, brought us up to date on the war. A Red Cross officer spent a number of days in camp, appearing we knew not whence, to provide radio facilities for the reaching of loved ones with messages from the camp.

"We had assumed that with the coming of relief, our troubles were ended, but the days lengthened, delays multiplied, and we were still detained in our little cells. Gradually the restrictions on our movements were lifted. We could stroll outside the walls and visit the city of Weihsien two miles distant. Supplies of clothing, toilet articles and army rations were flown in. A movie projector with films appeared from the skies, but best of all the long, golden autumn days were enlivened with the sound of saws and hammers. The whole camp was a bustle with movement. We were packing!! We were dismantling our quarters, stowing our bedding and books and clothes! We were alerted to leave!"

Both Fred and Jim felt it imperative that Frances get to Louise and Ruth in the States as quickly as possible to allay their anxiety and suspense over the three members of the family caught in the war in China.

"D Day" (departure) for Frances came September 25. She got to Tsingtao and then boarded the "Lavaca," an attack transport, for the homeland. For Fred and son, Jim, the day came on October 17 with a plane trip to Peking, courtesy of the U.S. Army Air Force.

***

REPRODUCED AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Issued by the intelligence office

Office of Chief of Naval Operations

Navy Department

CONFIDENTIAL

INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Received on Foreign Mail Room 1943 MAY 19 PM 3:16

Serial 32/43

FROM: Naval Attaché

AT: Chungking

DATE: May 1, 1943

SOURCE: Japanese, Chinese and Foreign

EVALUATION: C-3

SUBJECT: CONCENTRATION CAMPS, OCCUPIED CHINA.

During recent weeks the Japanese appear to have tightened the restrictions imposed on "enemy nationals" resident in the occupied areas of North and Central China. Official and semi-official Japanese announcements of the concentration of Allied Nations nationals are confirmed from independent sources.

A brief description of the more important camps is given herewith as compiled from available sources.

[click here]

REPRODUCED AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Ym

COPIED BY THE LONDON DELEGATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS COMMITTEE

North China

CIVIL ASSEMBLY CENTRE AT WEIHSIEN

(Shantung Province)

Visited the 9th and 10th November 1943 by Mr A. Jost, Assistant-Delegate.

Location:

The twin cities of Weihsien, in Shantung Province are reached by the railway line from Tientsin to Tsingtao. The city of Weihsien is enjoying the typical climatic conditions of North China, cold but dry in the winter and not too hot in the summer, with little rainfall throughout the year. The camp is outside the city of Weihsien, about two miles from the Railroad Station, located in the compound of the former Presbyterian Mission.

Established:

20th March 1943.

Camp Committee:

The inmates have elected their own representatives for the following 9 committees who are managing the affairs of the Assembly Centre directly with the Commandant:

Banking

Discipline

Educational

Food

General Affairs

Hospital

Medical

Quarters

Sports

[click here]

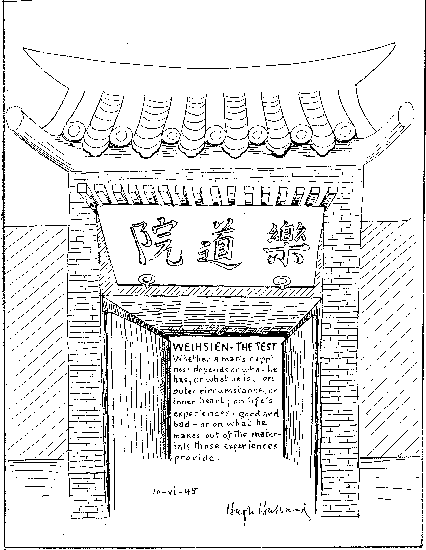

PREFACE

This book is about the life of a civilian internment camp in North China during the war against Japan. Unlike some other volumes dealing with such a subject, this one has no horrors to relate. We in the Weihsien camp suffered no extreme hardships of limb, stomach, or spirit. As the quotation from Brecht hints, our problems were created more by our own behavior than by our Japanese captors. Thus, compared to many other internment camps, both in Asia and in Europe, ours was in fact nearly an ordinary life. That is precisely what gives the story its interest and excitement, and why it is here told.

This was a life almost normal, and yet intensely difficult, very near to our usual crises and problems, and yet precarious in the extreme. Thus my story relates an experience within which one of those rare glimpses of the nature of men and of their communal life is possible. In our internment camp we were secure and comfortable enough to accomplish in large part the creation and maintenance of a small civilization; but our life was sufficiently close to the margin of survival to reveal the vast difficulties of that task. Had we been continually tortured and starved, no representative communal existence would have been possible; had our life been more secure, the basic problems of our human lot might not have manifested themselves so clearly. Thus, as the laboratory reveals the structure of what is studied by reducing it to manageable size and subjecting it to increased pressure, so this internment camp reduced society, ordinarily large and complex, to viewable size, and by subjecting life to greatly increased tension laid bare its essential structures. Because internment-camp life seems to reveal more clearly than does ordinary experience the anatomy of man's common social and moral problems and the bases of human communal existence, this book finally has been written.

The reader may well wonder how anyone can remember details and episodes of an experience twenty years in the past.

The answer is that I kept a rather lengthy journal during the internment in which were set down every fact and happening, every problem and its resolution, that came to my attention. Thus the main resource for these chapters stands very close to the life described, for the journal was largely written in camp and was completed shortly after my return to the United States in November, 1945.

I have often been asked why we did not try to escape. The reason was simple: a Westerner cannot wander unrecognized through the Chinese countryside as he might in Europe. His face and color identify him at once to any onlooker. He is thus infinitely vulnerable to any Chinese seeking the reward for his capture. To escape successfully, he must join a guerrilla band at once, who can hide and protect him. But guerrilla bands only wish to care for those who are strong, who possess some special skill that can help the group, and who speak fluent Chinese. Contacts with the guerrillas were, moreover, difficult and rare. Consequently, only two men were able to make such contacts as to allow them to escape; those of us who spoke little Chinese or had no special skills were never even considered.

Finally, it is inevitable that in attempting an analysis of our problems I should describe the "sins" as well as the virtues of the people in the camp. For this is essentially the subject of our story. Necessarily, therefore, this book seems to be describing the foibles, weaknesses, lapses, and selfishness of other folk, so that the impression might be given that I alone trod a saintly path through the life of the camp. At the outset it is important to state that any such impression would be false: no one stood apart from our common weaknesses and our common sins, and certainly I least of all. Different temptations beset and conquer different persons. While as an unencumbered bachelor of twenty-four, I may not have been as concerned as some others about space, food, and security, and so have been able to resist many of the temptations described in the following pages, nevertheless, I had my own moral problems in which I failed as miserably as others did in theirs. All men—each in his own way—need the forgiving grace of God if they would be whole. This is an essential note of the Christian gospel, and it has certainly been the continual lesson of my own life. If then the "sins" of other men seem to be described and analyzed in this volume, let it be remembered that another book on the camp could easily tell our tale with a different cast (doubtless including me, too), playing slightly different roles but enacting ultimately the same story. To save embarrassment all around, I have changed the name of every person mentioned in the book.

LANGDON GILKEY

Kitchen #1

While the Red Cross finds the food "good" and that the Belgian Government wondered whether to grant a "extra" to its nationals interned, here is the daily diet of an internment camp, described by an anonymous Belgian (probably from Kaiping mines):

Morning: kind of gray dust dissolved inwater, Sunday, holiday, water with a little rice in it, no salt or sugar

Noon: "stew" a little fishy, a mixture oflemon grass, turnips, water dishes, peelpotatoes and sometimes vague pieces ofbuffalo, still earth and sand - 1 or 2tablespoons rice

Evening: red beans or corn flour withwater - a ladle. Bread that I nevercould digest

MENU OF LAST MONTH

Morning: nothing

Lunch: a small piece of rotten tripe andgreen and a spoon rice

Dinner: every other day, red beans as Igave in the mine to my cow, the other day nothing, all dirty, disgusting, full ofwood and earthworms. They had onlyboiled water from the river, wherethere was much drinking as eating.

Eddie Wang's story ...

Mary Previte's version of "Libearation-Day" ...

[click on the picture]

![C-47 and evacuation to HOME ... [click here]](image/c47.png)

![buy the book [click here] buy the book](image/FrontCover.png)

![Shantung Compound - by Langdon Gilkey [click here] Shantung Compound - by Langdon Gilkey](image/Gilkey.jpg)

![kitchen number 1 - [click here] ktchen #1](image/Kitchen1.gif)

![Eddie Wang's version: [click here] August 17, 1945](../Highlight/image/parachutes.gif)

![Mary Previte's version of 'liberation day': [click here] August 17, 1945](../Highlight/image/image001.jpg)