1. The Russo-Japanese War

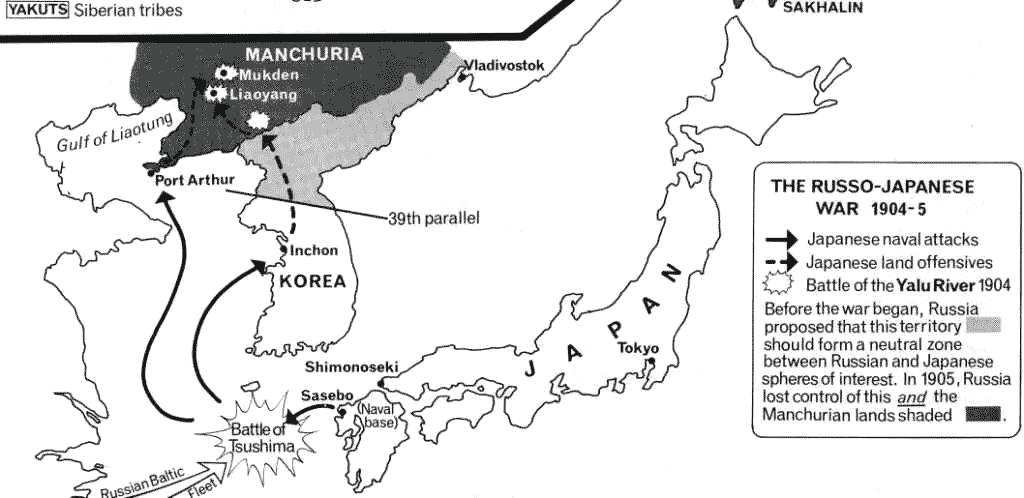

OWING to the situation at the end of the Boxer affair the clouds

of war began again to gather. It was a time of monstrous

complication between the chancelleries of Europe. Great

Britain had the Boer War on hand; Russia, Germany and

France were considering how our preoccupation could be

turned to their benefit and to each other's detriment; our

' splendid isolation ' principle could no longer work, so for

some years past there had been tentative approaches to an

alliance between us and Germany, which a mixture on the one

hand of procrastination and lack of unity of purpose and on the

other the ambition to challenge British sea supremacy rendered

futile; and so there grew the idea of a settlement of our

differences with France and of a rapprochement with that

country — which developed later.

That was roughly the state of affairs when, after the Boxers

had been put down, the Russians showed that where they were

they meant to stay — not only in Manchuria but in the north

of China proper. Out of this situation, and solving it, came,

in 1902, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which provided that if

either country was involved in war the other would come to its

assistance in the event of a third state intervening.

It is worth reviewing briefly what the policy of Russia was.

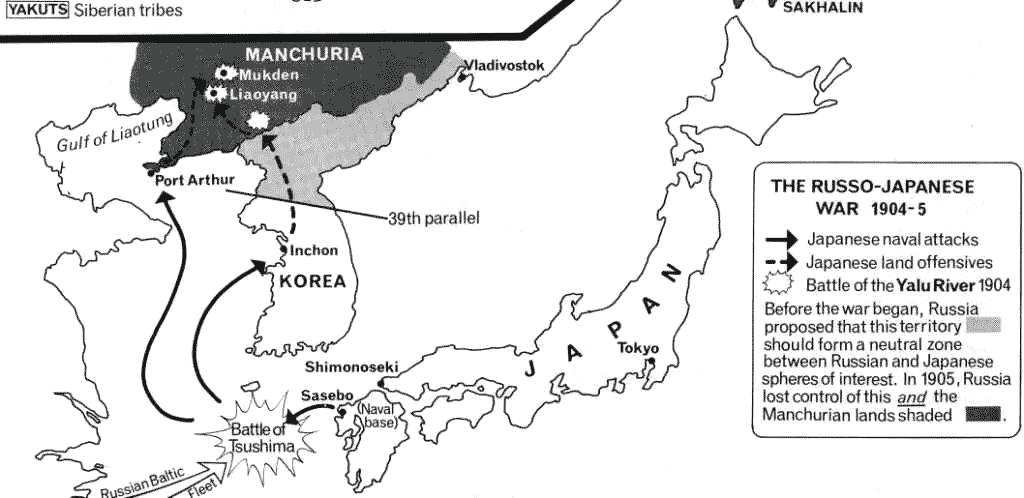

Up to 1860 her boundary was the Amur river and so her naval

port was Nikolaievsk — ice-bound for a large part of the year;

but then China, crushed by a war with France and England,

was forced by Russia to cede her seaboard from Nikolaievsk to

the Korean frontier, and so was created the naval port of

Vladivostok — a great improvement on the northern port.

But if one looks at the map it is plain how the Japanese contain

it; there is no egress to the ocean which is not dominated by

that country. It could not satisfy the Russians; and to the

southward lay Korea, studded with natural harbours, and

weak in her subjection to the double suzerainty of China and

Japan. So, as a first step — it was long before she had a chance

to attempt another — Russia tried to occupy Tsushima, a

Japanese island commanding the southern channel to the

ocean; but Great Britain shooed her off.

Then came the war of 1894 between China and Japan, when

the former ceded to the latter the Manchurian littoral from

Korea to the Liaotung Peninsula, including Port Arthur, the

Chinese naval port. The Russians did not like it. If

acquiesced in this cession would permanently block their game;

so they persuaded France and Germany — they nominally failed

with England — to join her in bringing pressure to make Japan

give up her spoil of war; and against such pressure Japan was

helpless. She retired and — wise little country that she was —

proceeded at once to make her preparations for the future.

China, of course, was grateful and so yielded to Russia's claim

to be allowed to build a railway across Manchuria from

Vladivostok to cut off the great arc that was caused by the

loop of the frontier formed by the Amur river; and where

that railway crossed the Sungari river was built the great

Russian city of Harbin.

Three years later, Germany started the policy of grab by

seizing Tsingtau because two German missionaries had been

murdered. Thereupon Russia demanded and obtained the

lease of Liaotung Peninsula — which so short a time before she

had made the Japanese relinquish — and the right to join it to

Harbin by rail. England followed with the lease of Weihaiwei,

as an offset to the Russian menace; France followed with the

lease of Kwangchow-wan, and Italy, without a shadow of

excuse, tried but failed to secure a lease of Sanmen Bay, in

Chekiang Province.(1)

1 — I advised the Chinese Admiral at this time that in case of the Italians

using force he should, regardless of all consequences, throw his little fleet

against them.

These facts, already told, require to be repeated here. Partly as a consequence of these indignities

there came, as has already been explained, the Boxer uprising

of 1900, and with it another chance for Russia to further her

desires. Realizing eventually that China was not to be partitioned, she limited her immediate ambitions to Manchuria;

but her threat extended to Korea. The representations from

other Powers on her acts resulted in an exhibition of tortuousness and mendacity that is possibly unique in the annals of

diplomacy. It was during the hatching of this situation that

Lord Salisbury referred to Count Ignatieff as the biggest liar

he had come across in his political experience.(1)

1 — Ten Years at the Court of St. James, by Baron von Eckardstein.

Russia threatened Korea, and, if she occupied that country,

she would dominate Japan and the Far East in general. That

she intended to do it was so evident that in February 1904 little

Japan struck at her giant neighbour.(2)

2 — An illuminating exposition of Russia's actions in this matter is given in

Count Witte's Reminiscences of the Reign of Nicolas II., of which the following

is a translated summary:-

When the Germans seized Tsingtau, Russian war vessels with troops

were sent to Port Arthur, and the Russian Government demanded a lease

of the Kwantung Peninsula: a demand which was at first indignantly

refused by the Empress Dowager. Count Witte, while disapproving of

the act, knew that the Tsar — egged on by the Kaiser for his own purposes

— was determined to have Port Arthur, even if the use of force was necessary

to that end; so he cabled a private message to Li Hung-chang pointing out

the inevitability of the occupation and promising him half a million roubles

for his support. That support was duly given and with success, and the

bribe was duly paid. " Thus," says Count Witte, " was taken that ill-

omened step which led to future developments culminating in the tragic

Japanese war and our internal troubles."

In view of the fact that only a few years previously Russia had been a

party to forcing Japan to relinquish her war-won occupancy of the Kwantung

Peninsula, Count Witte stigmatizes the Russian seizure as an act of unprecedented duplicity.

The unexpected seriousness of the attitude of Great Britain and Japan

about the seizure alarmed Muravieff, the Foreign Minister, for he had

assured the Tsar that it would cause no trouble. It was thus that, in fear

of a conflict with Japan, he abandoned the position of great influence which

Russia had gained in Korea; he withdrew his Adviser to the Korean

Emperor, his military instructors, and his other agents; and he signed

an agreement definitely admitting Japan's predominating influence in

the country.

It was early breach of that agreement that brought about the war between

Japan and Russia.

In the development of this situation I took a keener interest

and formed more definite opinions than in any of the problems

with which the Far East became involved. For this there were

several reasons. Although it was Chinese territory that was

in dispute, China was hardly a party to the quarrel. It was the

sick Chow Dog's bone that was being fought for by the Wolfhound and the Terrier. So with the elimination of that nightmare of intangibility, which China as an active factor always

means, the points at issue seemed — though they were not really

— comparatively simple. Then I was strongly antagonistic to

the Japanese. That was only natural by reason of their victory

over China; but of course I had admiration too and appreciation of the high chivalry which they had shown at Weihaiwei.

Of the justness of their quarrel there could be no question;

they were — though the immediate factor was the Chow Dog's

bone — fighting for existence. But I would not have them on

the continent — especially in China — at any price. Of the two,

as grabbers of Chinese territory, Russia would be the lesser

evil. I held this view most strongly and had maintained it

with some measure of success in my argument with Chirol. I

had sympathy with Russia in her railway scheme. Look at the

map and see the great temptation — when the break-up of China

was a seeming probability — to possess the country through

which that railway ran. So I considered that, if war — with all

the evils that would inevitably result, whoever won it — could

be averted by acquiescing in a Russian annexation of Manchuria

to the northward of her railway, it should be agreed to.

In July 1903 I went home on nine months' leave, accompanied by a sister who had been paying me a visit; we travelled

by the Siberian railway, and I saw something of Russian

preparations — the sidings were crammed with vanloads of men

and horses and field-guns. My sister became indisposed and

at St. Petersburg laid up, so I went to the Embassy for advice

about a doctor. There I met Spring-Rice, who in the absence

of the Ambassador was Chargé d'Affaires. I did not volunteer

my views, but he questioned me and showed great interest in

them. It happened that owing to the renovation of his quarters

he and the Military Attaché had their meals at the hotel where

we were staying, and I was asked to join them. At Spring-

Rice's request I wrote a memorandum on the situation, as I

saw it, for transmission to the Foreign Office. He warned me

that my association with them would make me subject to

suspicion by the Secret Service and that therefore I should on

no account keep a copy of my paper and that I should be careful

to burn my blotter. But I was vastly pleased with what

seemed to me the importance that had so unexpectedly fallen

on me. A memorandum to the Foreign Office ! I must keep

a copy, and I did so, placing it in my despatch-box, that in my

portmanteau, and both locked of course. Spring-Rice was

right; for just before we left St. Petersburg I discovered that

the paper had been stolen. It was well for me that the opinions

I expressed were so favourable to Russia; otherwise I should

have been arrested as a spy.

There remains a curious sequel to that episode. My companion in the coupé on that journey to the frontier was Garfield

— a Russian of English origin. Some years before I had known

him quite well in China; he was then connected with a

Russian Government mission in Korea; and now this seemingly accidental meeting. For was it accidental on his part?

I cannot give the reasons for the suspicion that grew on me;

they were vague but based on several facts, and in the aggregate

convinced me that Garfield had been sent to find out what he

could about me and my business.

Spring-Rice had arranged for me to see the Foreign Office;

I had some interesting conversations there and learnt that Lord

Lansdowne had read my memorandum; and then of course

they dropped me. I had one other shot at propaganda about

another matter — the saving of China from partition. Fearon,

a leading American merchant of Shanghai, was in London; I

gave him a memorandum which he delivered as a speech before

the Chamber of Commerce at New York; and later I had the

satisfaction of hearing Sir Robert Hart express pleasurable

surprise at the soundness of a merchant's views.

In December I realized that there was no longer any hope

that war would be averted, and, as I wished to have a hand in

neutrality affairs, I sacrificed two months of leave, and in

January left for China via Suez. I had added to my stock of

books on naval warfare and International Law, and on that

journey read them up and thought about how exterritoriality

would affect China's functions in neutrality. But war broke

out two weeks or so before I reached Shanghai; China had

made her declaration of neutrality, and Hobson, the Customs

Commissioner, was advising the local Chinese officials about

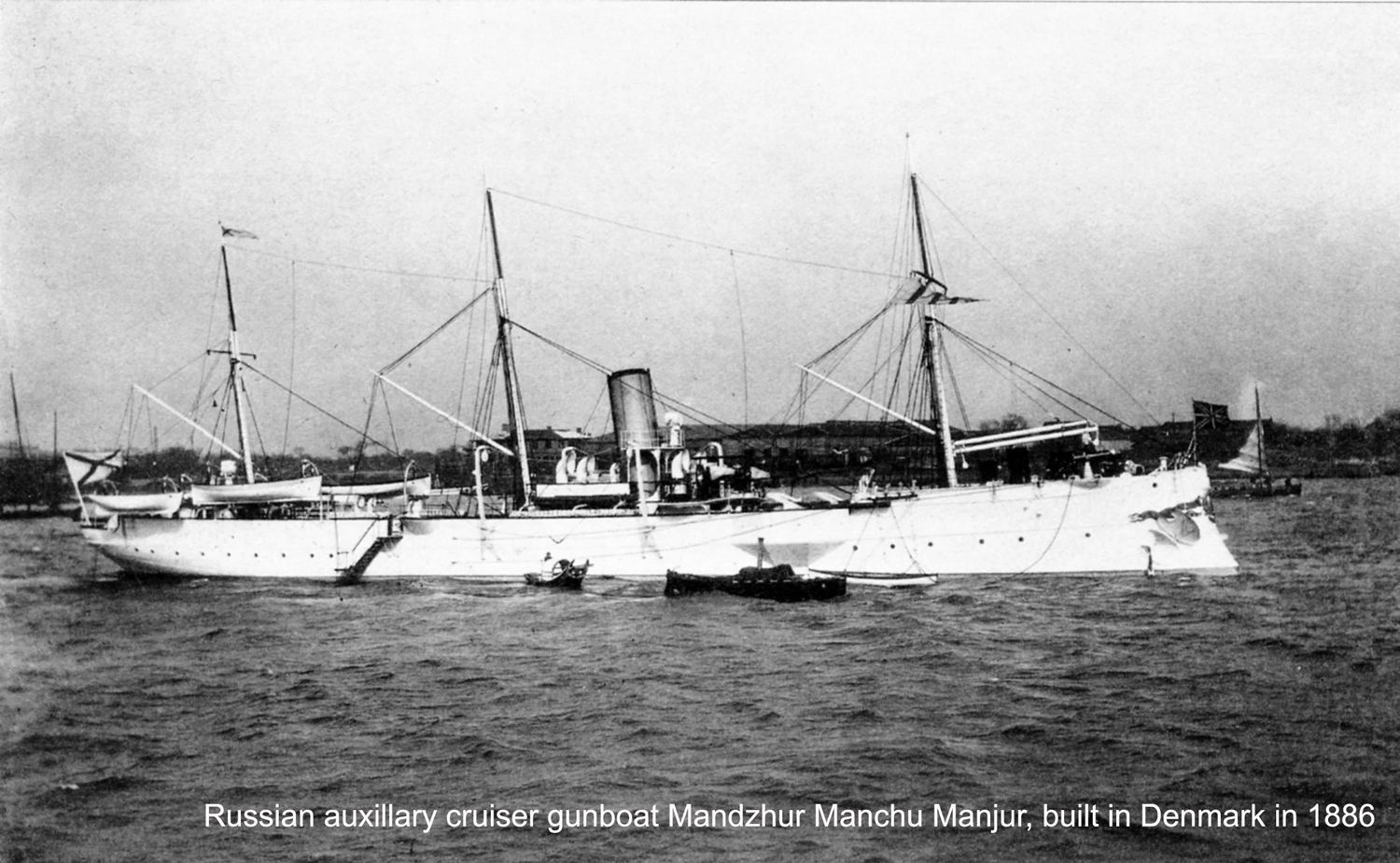

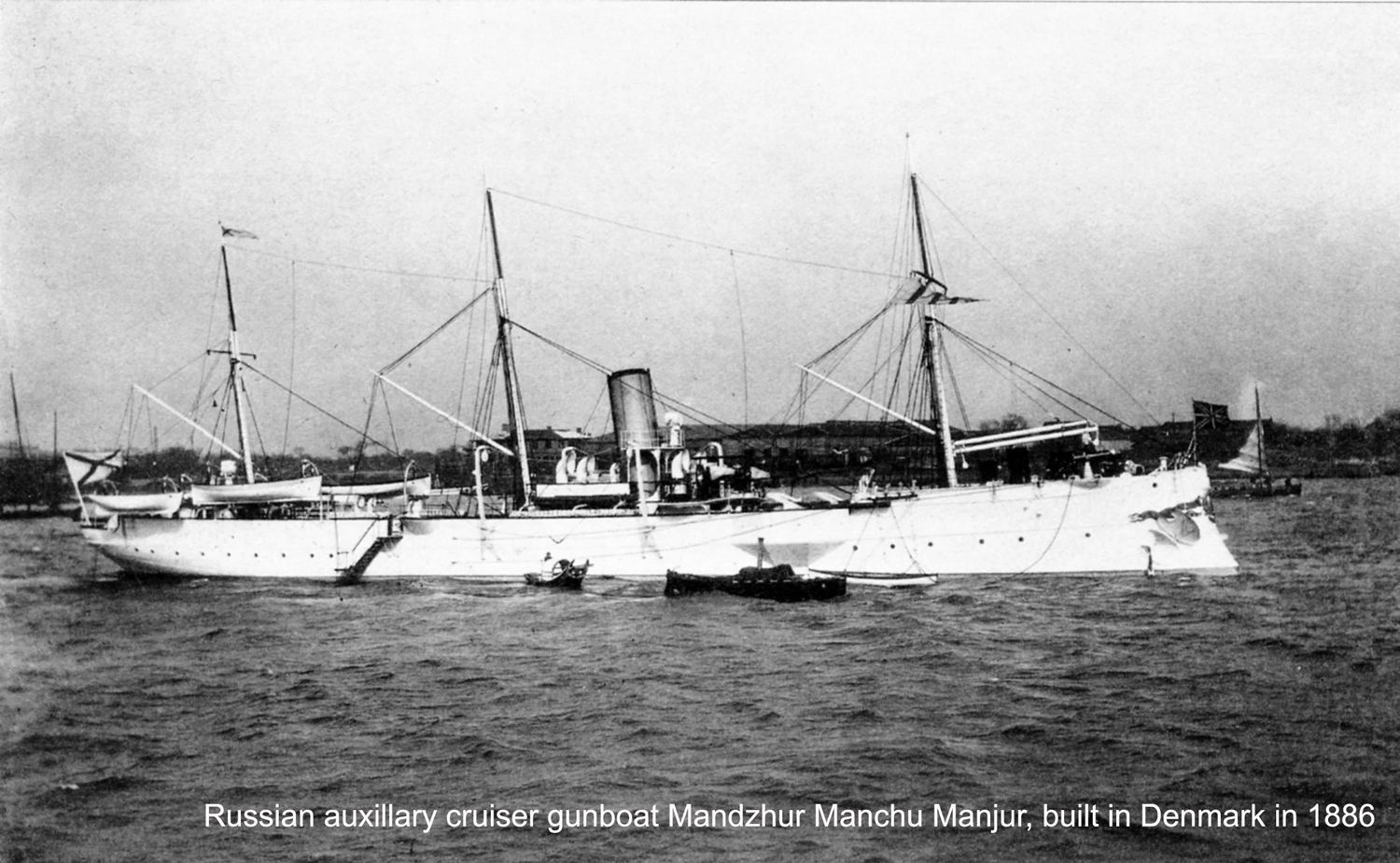

dealing with the Russian gunboat Manjur, which had taken

refuge there.

Hobson, a very senior man, had been one of

Gordon's officers in the Taiping days, and might have known

something about the practices of war; but the advice he gave

was radically wrong. Neutrality duties are those of an international policeman — they are essentially executive; yet, instead of acting on that principle and interning the vessel out-of-hand, he made the matter a subject of discussion between

the Taotai and the two belligerent consuls and consequently

at Peking between the Government and the two Ministers

concerned; and so the duty, which in any case would be A

difficult for China, was made much more so by this wrong

beginning.

I could not intervene; the thing had gone too far, and

besides I received instructions from Peking to attend to the

barrier removal at Canton called for by the Mackay Treaty.

That affair and others resulting from my sojourn in the South

employed me for over a year. I returned in May 1905, and

most opportunely from the standpoint of my neutrality

ambition, for a week later the transports of Admiral Rojestvensky's fleet arrived at Woosung, and a few days later that fleet

was defeated and annihilated off Tsushima — the island which

in 1860 the Russians had tried to occupy.

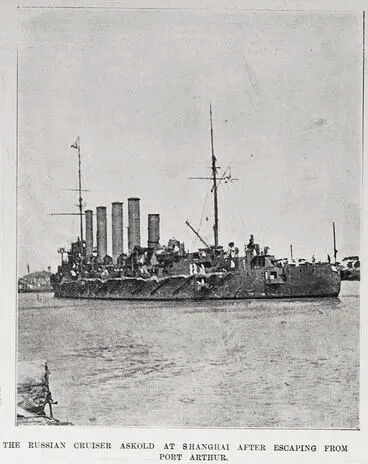

In the previous August the Russian war vessels Askold and

Grozovoi, having broken out of Port Arthur, which was invested by the Japanese, took refuge at Shanghai. Again there

was that exhibition of wrong-dealing with them, so now, with

the remnants of the Russian fleet seeking protection at Shanghai

and Chefoo, the time was ripe for me to take a hand. I discussed the matter with the Chinese Admiral and with Hobson,

and then I went to see the Viceroy at Nanking — the same

Chou-fu whom I had known at Chinanfu — and it was arranged

that he would instruct the Admiral to follow my advice. So I

took hold of the affair. Dr. Morse, in his International Relations

of the Chinese Empire, says: ' The Chinese authorities learnt

their lesson from this experience (their dealing with the Manjur

and other early cases for internment) and on the arrival of

Admiral Rojestvensky's fleet in Eastern waters, the Coast

Inspector, W. F. Tyler, ... was appointed as neutrality adviser

to the naval Commander-in-Chief. Towards the end of May

1905, Russian transports functioning with the Russian fleet

... arrived at Woosung. They were promptly declared war-vessels by Admiral Yeh, the Commander-in-Chief; and were

given the choice of proceeding or of being interned. Admiral

Yeh refused to discuss the matter with the Consuls or allow the

local Chinese civil officers to interfere. Recalcitrant Russians,

who after internment refused to give parole, were placed under

arrest; and the important principle was enunciated and given

effect to that in the performance of neutrality duties China was

in no way limited by the extraterritorial rights of the belligerents.'

There was something very fascinating in the exercise of the

authority and judgment which this work entailed.(1) It was an

uncommon sort of duty; it needed a knowledge of precedents

— I had them at my finger-tips — but above all it needed a

policeman's faculty of executiveness and not a lawyer's faculty

of arguing; and I never had a moment's doubt about it all. I

find this entry in my very meagre diary: ` Saw I.G.; he was

very nice and complimentary.'

1 — I find the following letter from the late Admiral Sir Gerard Noel,

who was Commander-in-Chief on the China station at the time. It expresses an opinion on internment which is interesting: —

` Nov. 20th, '05.

Herewith the papers you kindly let me see. I think that the action you

took in the case of the Russian ships, and your advice on the subject,

was exceedingly sound and good; and that you managed a difficult

business with considerable skill and adroitness, combining moderation

with a good show of firmness. I see nothing to object to in the treatment you recommended respecting interned ships. . . . As regards the

internment of warships in general, that is quite another question, and one

which I sincerely trust will never become a law amongst nations, unless it is

qualified by the obligation on the part of the Neutral to destroy such vessels.

I consider that the act of a belligerent seeking shelter from the enemy in a

neutral port to be contrary to the spirit of honourable warfare, and indeed

cowardly and reprehensible, and should certainly be given no encouragement. It is the business of a warship — as part of the territory of the country

to which she belongs — and therefore not rightly subject to the protection

of internment — to go out and fight or surrender to her enemy.'

In this chapter I attempt to give a silhouette of history to

serve as a setting to my story, and there are other chapters

where I do the same; but all the time I am conscious of the

impossibility of history to really tell the truth. One picks out

certain features which seem salient because one knows about

them; but in reality they are no more than mnemonic labels

of one's meagre knowledge. What seems salient has no great

relation to the mass of complicated factors that really rule a

situation.

#