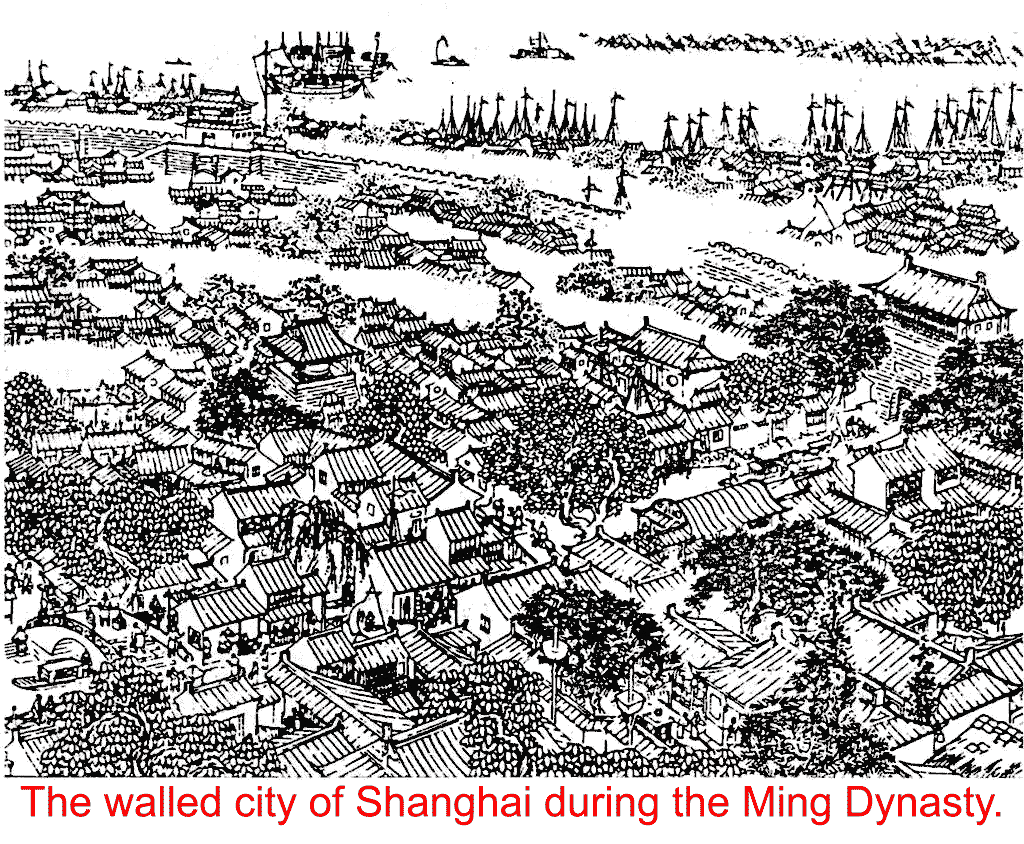

IN an earlier chapter, I said that the history of Shanghai formed

one of the backgrounds to my life in China. Here to begin

with is a little picture of its origin:—

The Genesis of Shanghai was this wise:

Long ago Duke Yü

said to Wang, let there be land. And there was land; for

Wang built a great stone wall in the shallow waters of what is

now called Hangchow Bay and connected it to dykes of mud and

reeds on the sand banks. So he controlled the movement of

the waters and bent nature to his will; the tall reeds on the

islands and the islets grew and spread, and the incoming and

outgoing tides bringing their load of silt, dropped it among their

roots — silt from the Himalayan plateau carried by the Yangtsze

river. Thus islands formed and grew and merged one with

the other, so that there were only creeks between. But still they covered at highwater springs, until seaward from the

mainland there came farmers who dyked the creeks and sowed

their crops in the rich fertile soil; and these farmers bred and

spread, and in the course of time made dry land of that great

area which lay between the wall and where Chinkiang now

stands. Thus was the sea changed to land, except for the

Tahu lake which stays a remnant of the former state. And

here and there, where rivers met, cities sprang up — Soochow,

Shanghai, Hangchow and many others. All this was brought

about by that great stone wall that, as legend has it, Wang

built long before the siege of Troy.

The building of that wall was no small matter, for in the

bay the water of the tide, as it flowed in, fell over itself and

formed one long rushing travelling wave, which, when the sun

and moon pulled together, had a height of nearly twenty feet

and a speed of many miles an hour; thus the wall had to stand

the pressure of that swirling mass, and so its stones were

dovetailed.

That, with a great wealth of detail, I gathered — by means of

a translator — from a set of rare old Chinese volumes, The Annals

of Soochow,(1) which at one time I possessed. It throws some

light on how the Great Plain of China, formed by the Yellow

river, grew until it reached its monstrous size. It throws

some light on how the ancient Chinese valley-dwellers spread

and bred on that highly fertile plain until their total in the

plains and valleys reached four hundred million souls.

1 — Whether the Yü named in these Annals was the Great Yü may well be

questioned. Dr. Morse, to whom this chapter has been referred, merely

says: The Great Yü functioned over 4000 years ago (2280-2205 B.C.).

The Hangchow bore was mentioned early in the fifth century B.C. An old

sea wall was rebuilt A.D. 713. The present wall dates from A.D. 910.'

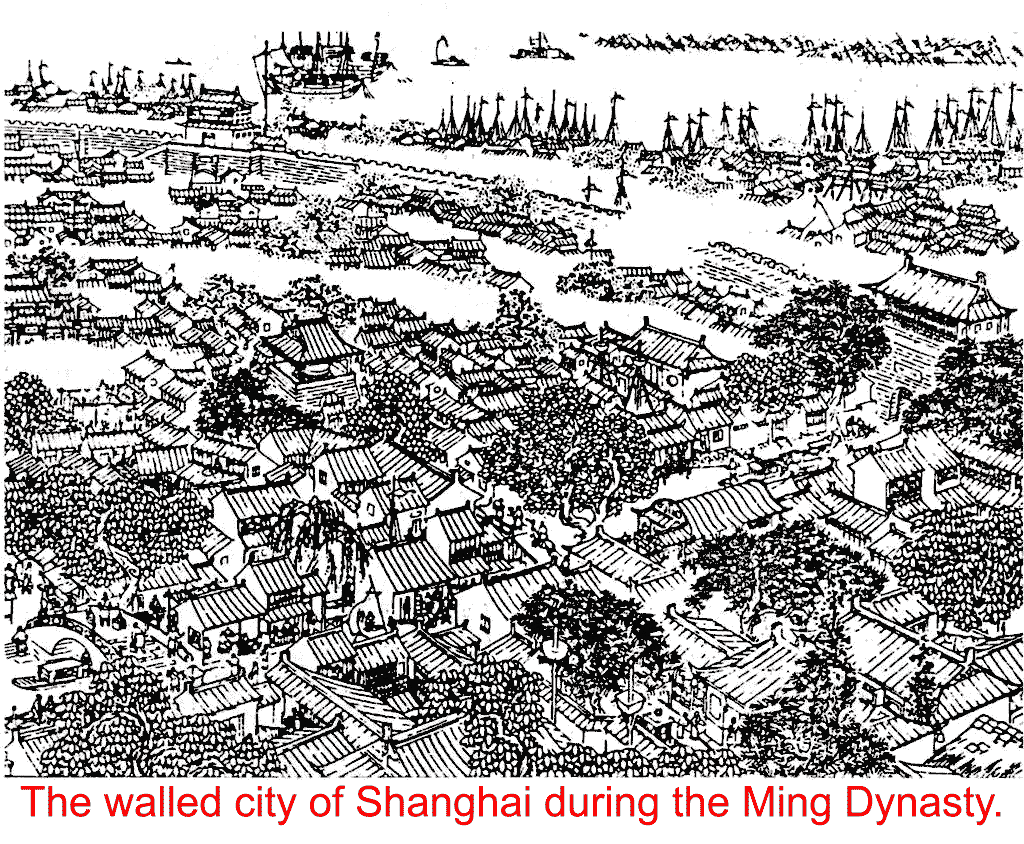

Now of those cities that sprang up in the plain that Wang

made, Shanghai was comparatively unimportant. It was unimportant until the British Fleet sailed up the Yangtsze river

to find a place of trade.

That was in 1842.(2) And then

commenced a curious piece of history, epochal in the future

story of the world. For by that choice Shanghai was destined,

in years still yet to come, to be the greatest port in all the world;

and to be a pivot on which world politics will move. It was

not made. It grew. It was organic in itself and a sport at

that — unique, like nothing else on earth.

2 — I am, however, informed by Sir John Pratt that according to his researches the native trade of Shanghai at that date was very great, far greater

than that of Canton, and with a tonnage comparable to that of the Port of

London. This is a revolutionary piece of information for us who thought

we knew something of our modern Chinese history.

In the early days of our intercourse with China we were

greatly affected by the glamour of the empire. The Chinese

were barbarians to us, of course (as we were to them), but

what magnificent barbarians — if not in general, in some

particulars. China was judged partly by the tales that Marco

Polo told of the wonders of the Court at Kambulu; and the

story of the invasions by Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan

was known better than it is to-day.(3)

3 — Regarding this Dr. Morse writes: ` China was judged less from

Marco Polo (thirteenth to fourteenth centuries) than from the Lettres

Edifiantes et Curieuses of the Roman Catholic missionaries of the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries, and G. L. Staunton and H. Ellis writing for the

English public in 1793 and 1816. The two last were in particular much

impressed by the high degree of civilisation of the Chinese. The British

officials who were chiefly impressed by the power of the Chinese Empire

and desired to treat it with great consideration were those in Downing

Street. When one of the governing class (Lord Napier, Sir John Davis,

Sir John Bowring, Sir Geo. Bonham, Lord Elgin, etc.) arrived in China he

at once saw and wrote that nothing but armed force would obtain any

concessions from the Chinese, and that two or three fifty-gun frigates would

be enough.

' The supercargoes of the East India Company at Canton were in a difficult

position. They objected strongly to submission to derogatory conditions

which their directors in Leadenhall Street tended to require of them; but

having protested to the Company they carried out their orders loyally.'

Some of our officials mistook the insolence of the mandarins

for a mark of the greatness and the power that they represented.

We could of course make war upon the country to secure a

decent trade arrangement, and later to break down her diplomatic isolation — that lay quite clearly within the limits of the

code — but it was an era of exactitude in conduct, and between

war and no war there lay a gap of no alternative. And so we

taught the Chinese, who hitherto had only known of force

whichever way it worked — for them or against them — the idea

of sovereign rights.

As an example of punctiliousness, of the compunction to do

anything that was not strictly proper according to the code,

consider the situation at Shanghai when in 1854, during the

Taiping Rebellion, it was threatened with incursions by the

Imperial troops, who were investing the City proper. It just

happened that we were not at war with China at that moment.

The settlement was in very real danger of being overrun by

soldiers out of hand; but its soil pertained to Chinese sovereignty; how then could foreign troops be landed to protect our

interests? But of course this punctiliousness was of an

academic nature, and of course a means of circumventing it

was found by a legal fiction or — to use the modern language of

the League of Nations — a formula. That formula is worth the

reading; it was laid down by Mr. Alcock, the British Consul, —

with the French and American Consuls — at a meeting of Land

Renters in 1854, which was assembled for the first time under

a new Code of Municipal Regulations:—

' The necessity now pressing upon the community for the

immediate establishment of a Municipality in some form was

to be traced to the impossibility, by any exercise of consular

authority, of making permanent provision for the security of

the settlement without a municipal constitution. And on this

part of the subject he deemed it most important they should

have a perfect, clear and correct knowledge of all the facts;

and see the true bearing of the question at issue upon the

position of the community, the naval forces and the civil

authorities, both foreign and Chinese. To give that cosmopolite community legal status: an existence as a body

capable of taking legal action and of lending a legal sanction to

measures required for their defence, there must be some organization to take the form of a representative council with municipal powers and authority. The functions to be exercised on

their behalf by such Council were no longer those of a Road

and Jetty Committee, but involved the protection of life and

property from causes of national disturbance in the country

where they were located, from sources of disquiet and danger

within and without the settlement, where a large native

population bid fair to dispute possession with the foreigner

for every rood of ground within the limits. And one of the

first acts of such Municipality, or rather one of the first and

greatest benefits naturally flowing from its creation, would be

the legalization of the many measures hitherto forced by a stern

necessity upon the naval and civil authorities on the spot, but

which could not be justified on any principle of legality.'

The compunction in this matter existed not only with the

Consuls. The British and American Admirals held the view

that for them to take part in the protection of the settlement

would constitute an act of war for which no authority existed.

Thus Mr. Alcock further said:-

` Neither Great Britain nor the United States, nor France,

had undertaken by Treaty to protect their subjects ashore in

Chinese territory, nor could they, by Treaty, legally do so

without the assent of the Chinese Government. As a matter

of self-preservation, however, the Municipal Council could do

these things.' And then came the legal fiction that the Council,

having that right but not the power to exercise it, had ` every

moral right to call in anybody and everybody to help it.' It

was on those grounds that the navies took a hand.(1)

1 — Seamen from the men-of-war may have been reluctantly used to protect

the settlement before the utterance of Alcock's dictum, but I doubt it. The

speech was made on the 11th January 1854, and the ' Battle of Muddy Flat '

— the only considerable fighting that took place — occurred on the 3rd April

following.

That happened in 1854, when the settlement had existed

for twelve years. I propose to tell — very briefly — its story

from the beginning, and I made that jump to the time of the

Taiping Rebellion to indicate the medium, as it were, in which

the organism of the settlement had its growth. It was a

medium of official compunction as regards the means to meet

the needs of the community. Consequently from an early

date the residents learnt to rely upon themselves, to develop

their governance as best they could by local arrangement with

the Chinese mandarins; and in that endeavour the Consuls

as a rule identified themselves with the community. It was

the diplomats who, having made no provision in the treaty

for the government of a settlement, opposed the growth of

means to meet that lack.

[click] The Treaty of Nankin 1842.

[click] The Treaty of Nankin 1842.

[click] "The Opium War" explained by David C. Hulme

[click] "The Opium War" explained by David C. Hulme

The Treaty of Nanking was signed in 1842. It opened

Shanghai and other ports to foreign trade and provided that

British subjects, with their families and establishments, shall

be allowed to reside, for the purpose of carrying on their

mercantile pursuits, without molestation or hindrance.' A

supplementary treaty signed the next year made brief provision

for the purchase or rent of ground and houses. There was no

word in either of the treaties as to the conditions under which

communities of foreigners were to live on Chinese soil. That

I think was inevitable. No one could foresee what the conditions of those communities would be; over the situation

hung the sanctity of sovereignty — that, in a peace condition,

must never be impugned; and, in effect, the policy adopted

was ` wait and see.' It must be remembered that even exterritoriality — freedom from Chinese jurisdiction — was not

included in the Nanking Treaty, though the principle was

already recognized. The Supplementary Treaty provided,

however, that regulations to govern the communities should

be drawn up jointly by the local Chinese officials and the

British Consuls; and it is important to note that no provision

was made for submitting such regulations either to the British

or the Chinese higher officials. I think that the framers of

the treaty knew that the solution of the problem of the governance of the settlements must be the result of a gradual give and

take and could not be — at all events at first — a subject for

diplomatic action.

The first regulations — named Land Regulations — appeared

in 1845. They defined the boundaries of the settlement, and

made provision for the construction of roads and jetties, a

Committee for the purpose being formed of ` three upright

merchants ' selected by the British Consul. All the power

under the regulations was centred in the latter, even in respect

of other foreign interests. That, of course, was an untenable

position, and British jurisdiction over foreigners in general

did not last for long.

The French had got their own settlement from the Chinese

in 1849, but for many years the French Consul was its only

occupant. The Americans did the opposite; they acquired

land and formed a colony in Hongkew in about 1848, and in

1861 organized a small police force of their own, but it was

not until 1863 that an American settlement was formally

arranged for; and immediately afterwards its residents voted

in favour of amalgamation with the English settlement, which

then took place.

For the first ten years the conditions in the settlement were

very primitive; Chinese authorities exercised full control over

all the Chinese there; and there was no organized police force

— either Chinese or foreign; though the regulations laid down

the right to hire watchmen.

We now come to 1854, to the time of the Taiping Rebellion,

when Alcock made that speech of his. So far there had been

no real municipality. There was the French settlement in

which the French Consul lived in solitary glory, and which later

had a history of its own; there was Hongkew, where some

Americans resided but without a formal settlement; and there

was the British settlement in which the British Consul,

assisted by the Committee of Roads and Jetties, reigned, except

that other Consuls governed their own nationals. Within that

settlement lived the whole community of whatever nationality,

and so the anomaly of a British domination grew and led to

difficulties, for example, about the use of ensigns other than

the British. In consequence the British Government decided

to give the settlement a status in which all had equal rights and

in which the special functions of the British Consul should

devolve on the Consuls as a whole.

In the details of this act the French and American Consuls

— there were no others at the time — collaborated, and then

were produced the Land Regulations of 1854. Now what

about that speech of Alcock? There is not a word in it to

show the reasons for internationalizing that are named above.

The reasons given are confined to that academic view of

legalizing armed defence on China's soil. There may well

have been a feeling of delicacy about referring, for example,

to that matter of the flags and cognate things; and the other

reason gave a better chance for rhetoric; but it was not eyewash. It was obviously considered a very serious affair, that

breach of China's sovereign rights in peace time, though it

makes curious reading nowadays. And so the Shanghai

municipality, carried in the womb of time for twenty years,

was born. It was a curious birth, brought about unconsciously

because it was ripe for happening, but consciously owing to the

fact that the joint parents — the three Consuls — were alarmed

at their responsibility in connection with the need for a breach

of China's sovereign rights. So they hatched their baby and

shifted their responsibility to it: they placed a crown upon

its head and rendered it obeisance.(1) In later years the successors of these Consuls repudiated the offspring of their

body; they tore the crown from off his head and made him

as subordinate as they could. But he never forgot the quasi-

royal birth he had and always hankered for his sceptre; and

being a lusty youth he fought for it and kicked against restraint

and subordination.

1 — But viewing this affair more historically and less picturesquely, one

sees that there may well have been other factors in the situation; and one

can feel confident that the principle concerned stood no chance of being

supported by the British Government for any length of time.

wbr>

Inaugurated with that great dignity of language by Mr.

Alcock the Municipal Council had to deal, when the Taiping

Rebellion was ended, with the condition of Chinese sovereignty

in the settlement. There were needs of government which the

Chinese could not meet; there were Chinese official acts

within the settlement that became beyond endurance; there

was the crying need for an organized police; so partly by

mutual agreement, partly by unnoticed evolution, and partly

by some pressure, there arrived in due course effective self-government by the Municipality. It succeeded, for example,

in suppressing the open functioning of the Chinese police within

the settlement, and that was by means of pressure to which the

Chinese yielded with reluctance. Dominating the situation

was the fact — unexpressed and perhaps not even thought of —

that, while there was antagonism between Chinese right and

needs of the community on which the Council's acts were based,

there was a very real community of interests between the two.

What was good for the settlements was good for China; what

was bad for China could not be good for the settlements.

That unstated principle was the soil in which grew — step by

step — the unique governance of Shanghai. It was a beneficent

anomaly outside the scope of treaty stipulations. In the

years to come the diplomats stood off and watched the strange

growth of their abnormal and precocious ward and did not

like it; they could not help materially because the thing was

so illegal; they could not always interfere materially because

what was done was so often obviously necessary. And even

when in much later years an occasion arose where their interference was needed with great urgency it was not forthcoming:

the power to do so had atrophied by lack of use.

In general that growth, so irregular but so efficient in its

process, was very admirable — this gradual creation of a constitution by a Council formed of business men — with the

Consuls in the offing. It is what I meant when in that sketch

of its origin I said that Shanghai was organic in itself and a

sport at that.

There is a curious feature about the history of the French

settlement. It was formally included within the scope of the

code of 1854, but after promulgation the French Minister

repudiated that inclusion without making the fact public.

Some ten years later, when that settlement began to be inhabited, its independence, as notified by its own set of municipal

regulations, came as a great shock to the rest of the community.

There remains the question of the jurisdiction over the

Chinese in the settlement in those early days. In that matter

the British Consul from 1852 or earlier functioned specially.

Acting magisterially in association with the Chinese officials —

a Weiyuan doubtless sitting with him — he dealt with trivial

offences; while serious ones were sent to the City magistrate.

Later, the American Consul — at least — took a share in these

proceedings.

From 1854 to 1861 the Taiping rebels ravaged the country

for many miles around, and the wretched peasants flocked to

the settlements for refuge. At the end of '62, by which time

a thirty-mile zone had been cleared of rebels, there were a

million and a half of refugees, and a year later — at the fall of

Soochow — these were joined by perhaps another quarter

million. Then they began to dribble out, and more rapidly

after Nanking fell in July '64, so that at the end of '65 the

Chinese in the settlement were reduced to less than 150,000.

To meet the problems resulting from this monstrous influx

a Defence Committee had been formed; and, when the situation began to remedy in '62, it turned its mind to other things.

It realized the arrival of a nodal spot in the history of the

place. Obviously it was the moment to think of what had gone

before and what the future might produce; and to consider a

new departure. So that Defence Committee of merchant

princes put their heads together, and with the words of Alcock

about the great importance of the Council still pleasantly

within their memory, put forward the proposal that the settlement should have a Free City status — and so a magistracy of its

own. It was a most natural ambition. Equally natural was

Sir Frederick Bruce's condemnation of it. That Minister took

occasion also to criticize the Council's policy in general — their

disregard for the letter of the treaties; for example, the encouragement which they had given to Chinese to live within

the settlement, and the restrictions placed on the taxation of

the Chinese population there by their officials.

And so the inevitable happened. In 1864, Sir Harry Parkes

was British Consul. With a very virile personality he was the

exponent of the strict observance of Chinese rights, more or less

regardless of local expediency as viewed by the merchants; and

he, in negotiation with the local Chinese authorities, produced

the Mixed Court system. In 1869 a new set of Land Regulations

were issued by the foreign Ministers under which the fiction

of 1854 — that the authority for extraordinary action rested with

the municipality — was discarded. A Court of Consuls was

formed to whose jurisdiction the Council was now subjected;

and, in effect, there was a reversion to the principle of Consular

guardianship of 1845.(1) But in spite of this curtailment of its

powers and the disapproval of its aims and policy the Council

continued a potent force, and went its way regardless to a great

extent of the dicta of the diplomats.

1 — This set of regulations was never submitted formally to the Chinese

authorities for their consent. This, however, was not due to any lack of

desire to do so, and still less to any disregard for China. It was due to

certain cogent (reasons which so far, I believe, have not been made public.

There is ample evidence that these regulations were tacitly accepted by the

Chinese authorities.

It should be understood that in what goes before I am not

contributing to history. I am merely trying to give a picture

from a certain point of view; so I stress and exaggerate to some

degree the fictional grandiosity of the Council's birth. Thus

does the artist, unconsciously perhaps but rightly, depict the

moon upon his canvas at twice its real size, and so, however

obscure the reason may be, gives it its proper value in the

picture.

For the next development in the story of the settlement it

is necessary to turn to general Chinese history for a little while.

The year '98 was pregnant with evil and misfortune. Four

years before there had been the disastrous war with Japan, and

now foreign aggression was at its height. The country was

seething with discontent; the mixture of anti-foreign and anti-dynastic fermentation was in progress, which two years later

led to the Boxer movement. But other forces were in play:

those of the desire for reform as opposed to revolution; and

Kang Yu-wei was the leader of that movement. Officials

were in it, if they were not revolutionaries; Chang Chi-tung, a

great viceroy, became ardent in its cause; and then Kwanghsü,

the thirty-years-old Emperor, became inspired with the same

idea and brought Kang Yu-wei to court. Kwanghsü had

reigned since '89 when the Empress Dowager had relinquished

the regency, though she remained a power behind the throne

and something to be reckoned with. So when the Emperor's

edicts for reform became extravagant, she emerged and intervened, and he knew that her purpose was to lock him up. So

Kwanghsü appealed to Yuan Shih-kai, who then was Provincial

Judge of Chili and in command of troops, to turn the tables

on her and lock her up instead; and a feature of the scheme

was that the Viceroy YungIu, a partisan of the Empress

Dowager, should be summarily beheaded. Yuan is said to

have betrayed the Emperor to Yunglu, but there is some

doubt about the extent of that betrayal. Anyhow the Empress

Dowager won the day, occupied the throne again, immured

the Emperor in the Pavilion of Peaceful Longevity, and then

started on the extermination of reformers. Dr. Morse in his

International Relations of the Chinese Empire writes of decapitations at that time; but I was told of gruesome things, for

example, of a victim in a heavy coffin being sawn in two —

and lengthwise.

I will digress here to say something of the Emperor. I

fail to understand why he should be handed down in history

as a poor thing — a subject for contemptuous pity. He is

said to have had an immature mind and to have been

mentally anaemic. Yet the initiative in action for reform was

his, however much he may have been guided by Kang Yu-wei.

He issued some forty edicts on important matters in a hundred

days; and when his liberty was threatened he tried to take

most daring counter measures. He was physically weak; it

is likely that the Empress Dowager encouraged him in habits

that would make him so; and yet in spite of it he made that

strenuous effort to redeem his country. That he was unwise

to rush things is obvious; but so have others been without

being branded for it as semi-idiots. That after his downfall

he collapsed is not astonishing; he was a victim waiting for his

certain doom, which took so long to come, for it was ten years

later that it overtook him, whatever were the means employed;

and in between, when the Empress was raging in her preparations to flee from her capital in the Boxer time, he had to look

on while his beautiful PearI concubine was thrown down the

well that lay in front of the Pavilion of Peaceful Longevity.

Kwanghsü made a noble, however unwise an effort, and he

died a martyr to the cause of progress.

At the time of the Empress Dowager's coup d'état the Chinese

officials at Shanghai had for long relinquished the right to

make arrests within the settlement, though every now and then

they did it just the same — but surreptitiously. But they had

not lost their right of jurisdiction over their nationals who,

without being permanent residents there, took refuge within

its borders. These were handed over on request with a

minimum of formality. As for the Chinese residents, the

Mixed Court dealt with them except when the crime was

beyond its competence to deal with, and then these also were

handed over to the purely Chinese court.

The Empress Dowager was raking out the cities for reformers.

The settlement, although not as yet a certain refuge, was

safer than elsewhere, and reformers congregated there for

such protection as it gave and for the means of going overseas

if necessary; and of course the Empress Dowager wished to

rake the settlements as well. I have forgotten whether she

succeeded in netting any victims before the Council, supported

by the Consuls, took another step in the arrogation of Chinese

legal rights. It refused to hand over a refugee except when a

prima facie case was made out against him in the Mixed Court

as a common criminal; and political offenders they would not

hand over in any circumstance. The act was more than merely

justified; there was nothing else to do; to hand over reformers — worthy and patriotic men — to be killed and worse

was quite impossible. The act served China well; again was

shown that principle of community of interests, however

antagonistic rights might be. It was J. O. P. Bland, the

Municipal Secretary at the time, now a publicist and the author

of several books on China, who led in that affair of '98.

A few years rolled by; the Boxers came and went; Japan

and Russia fought on Chinese soil; the Manchu dynasty was

ejected from the throne; Yuan became President of China, and,

with the blessings of the Western world, made himself mere or

less dictator, on which rebellion broke out against him. That

was in 1913 — the monarchical affair came later.

So from the time when the Right of Asylum was established

in 1898 to the time of the first rebellion against Yuan was

fifteen years. Bland, had he stayed, could have been counted

on, knowing as he did the genesis of that measure of emergency,

to guard against a gross misuse of it; but he had left. Other

people came and went: members of the Council, busy men of

affairs; members of the Chamber of Commerce; members of

the China Association — they would include a barrister perhaps,

but all were busy. And the Consuls came and went just

ordinary men who happened to be consuls instead of something

else and with no special brand of intelligence; and they dealt

with yesterday, to-day, and tomorrow; fifteen years ago did

not come within their purview.

A feature of Shanghai was its mutability; a constant change

of its constituent parts; there was continuity of growth because

it was a living and strongly healthy organism, and to some

degree it had a corporate instinct like the instinct of a

herd, but there was little continuity of thought about the

process of that growth. So what with the outside interests

of these people in business and play; what with mere

inertia and uninteIIigence; and above all what with the

working of the unexpressed practice of the Council that

' what they had they held,' the Right of Asylum continued

to function not only when the purpose of it had expired but

when the operation of it was inimical to every interest except

that of common criminals. In ninety per cent. of cases prima

facie evidence against a murderer and an eye-gouger — the

latter a specialty in local crime — was impossible to get. Intimidation of witnesses alone prevented it — they too would

have had their eyes gouged out. So Shanghai became a place

where criminals fleeing from the process of the Chinese courts

were immune from interference; the settlement was their

headquarters. And from that to allowing stations where

rebels were recruited to fight against the Central Government

— that happened in the French settlement — was but one

step more.

Here comes the curious thing. The detriment and evil of

the situation was realized; it could not but be. But somehow

in those fifteen years the Right of Asylum — its origin forgotten

— had come to have the glamour of a sacred principle; it was

as sacrosanct as a sacrament; and it took on a special British

cloak of immutability as an example of our virtue in ' playing

cricket ' in all affairs of life — even to our detriment.(1)

1 — A. M. Kotenev in Shanghai: its Mixed Court and Council quotes a

proclamation to show that the Council took prompt action to prevent an

abuse of the Right of Asylum. It did take certain steps when the scandal

of the situation became outrageous; but even then they were quite inadequate.

By 1913 I had been in touch with settlement affairs for

eighteen years. No one else had such a continuous official

connection with the place. I had of course no official connection with the municipality, yet in one way and the other my

business had brought me in close contact with Sino-foreign

affairs; and in a limited way I had made a study of the growth

of the Council's powers and policy. There came the second

revolution and its suppression for a time; and Admiral

Tseng, who now became Military Governor, was the leading

Chinese spirit in trying to tidy up the situation and put down

the extra brand of lawlessness which that revolution carried

in its wake; and then of course he came up against the

Right of Asylum. Tseng appealed to me about it — the unfairness of the thing, the obvious detriment to Chinese and

foreigners alike, the folly of a procedure whose only function

was the protection of the criminal; and that was how I came

into the matter.

The Inspectorate gave me leave to act — again that generosity

of trust. With reluctance my chief even gave me leave to

come out in the open, but I did not use it; I always feared

publicity and the jealousy and other things it caused; so I kept

behind the screen and tried to push others into the limelight.

My object was to get some smart young barrister to take the

matter up, to talk at a meeting of the ratepayers, to urge the

China Association in the matter — to be a publicist in fact.

Oppe promised me to do it, but the Great War was on, and

he volunteered and was killed. Then I tried another who

co-operated for a time, but later dropped the matter.(1) So

I was left to do the best I could alone by talking privately to

public men and writing to the papers.

I have the letters that I wrote him on the subject; they may be useful

later to one who writes the detailed history of the settlement.

Some time later Grant-Jones, the British Mixed Court

Assessor, with whom I had not at that time discussed the

question, started, and apparently on his own responsibility, a

new procedure for handing over criminals, which went a long

way towards what Tseng and I desired; and I for one gave him

great credit for his wisdom and pluck in breaking with tradition.

Whether my agitation had any influence in that change I

never knew.

In November 1915 came Tseng's murder. He was shot in

the street in the International Settlement. The presumption at

the time was that he had been killed by the Kuomintang, but

even then there were whispers that Peking was responsible

for the deed. He had been reticent with me about the monarchy affair, though he expressed to me his disapproval of what

he knew to be a monstrous folly, and he showed grief because of

his devotion to Yuan Shih-kai. After the tragedy I recognized

the portents of his recent manner: he knew, I think, what was

with certainty impending over him, and made no effort to

avert it. But I am still in doubt as to who arranged for the

killing of my friend.

My stricture on Shanghai covers a very brief period. Until

the second revolution that mad obsession of the sanctity of

asylum did no great harm except to the settlements themselves.

The period of serious harmfulness was brief — was measured

by a year or two. An obsession is a stubborn thing; a cure

is slow. There was a strong inertia against a change in

practice, but it gave way before a slow recovery of sanity.

That folly of asylum favoured — quite unintentionally — the

party that is now in power, and which more or less must stay

so; and thus it is not a card which can be used by it against

Shanghai. But apart from that it cannot be put in the balance

against the great benefits which the settlement has conferred

on China. Putting that temporary error on one side, Shanghai

has been a centre of stability, of sanity, of progress; it has

been an object-lesson of many things: of governance, of

sanitation and, above all, of justice in legal procedure; and

it has been a refuge for the persecuted.(1)

1 — I purposely abstain from any comment on the immediate and stupendously important problem of Shanghai. The subject is far too controversial for this book.

#

[click] The Treaty of Nankin 1842.

[click] The Treaty of Nankin 1842. [click] "The Opium War" explained by David C. Hulme

[click] "The Opium War" explained by David C. Hulme