3. The Chinese Navy

The way of the Chinese constitution was to govern by and

through the Viceroys of the provinces; so it was Li Hung-chang  — of the northern province Chihli — the most powerful

satrap of that time — who owned a fleet. Nanking and Canton

also had their fleets, but their craft were obsolete. Li Hung-

chang's was very different. His ships were up to date — two

battleships with ten-inch guns, armoured cruisers, light

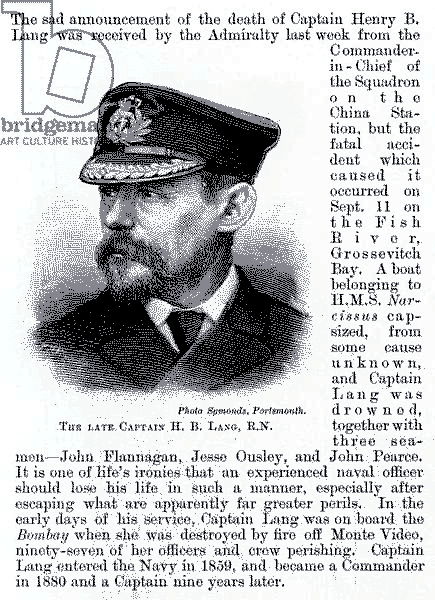

cruisers and torpedo boats — and he had engaged an English

naval officer — Captain Lang — to train the officers and crews.

— of the northern province Chihli — the most powerful

satrap of that time — who owned a fleet. Nanking and Canton

also had their fleets, but their craft were obsolete. Li Hung-

chang's was very different. His ships were up to date — two

battleships with ten-inch guns, armoured cruisers, light

cruisers and torpedo boats — and he had engaged an English

naval officer — Captain Lang — to train the officers and crews.

Ting Ju-chang  — was the Admiral; Lang also held that rank,

but in an ambiguous Chinese form which might mean anything

from the second in command to an adviser with the rank of

admiral. Lang believed it was the former, so, when Admiral

Ting was called to an audience at Peking, he claimed to take

his place; but Liu Poo-chin, the senior Commodore, maintained that Lang was only an adviser and that the post was his.

— was the Admiral; Lang also held that rank,

but in an ambiguous Chinese form which might mean anything

from the second in command to an adviser with the rank of

admiral. Lang believed it was the former, so, when Admiral

Ting was called to an audience at Peking, he claimed to take

his place; but Liu Poo-chin, the senior Commodore, maintained that Lang was only an adviser and that the post was his.

Peking supported Liu, and Lang resigned. It did not seem a

matter of world importance at the time; but it was. It was

the decadence of the fleet after Lang had left it that caused the

Japanese to venture on their war with China about Korea and

gave them victory; it was their holding of Korea that brought

about their war with Russia; and it was the weakening of

Russia in that war that gave Germany the chance to have a

shot at world dominion.

It was shortly after Lang resigned — in 1891 — that we lay

at anchor with the Chinese fleet in Kowloon Bay on the outskirts of Hongkong; and there I made my first acquaintance

with it. I visited the flagship and commenced my friendship

with Woo the Flag-Lieutenant, Tsao the Gunnery Officer, and

Commander Li, which lasts until to-day. I was vastly interested in that battleship and all they showed me, and left full

of admiration for the Chinese fleet.

In 1893 Li Hung-chang held a review of the fleet in Northern

waters, and I happened to be there in a Customs cruiser. So

I saw the

Chinese fleet  —

doing its little best after a few years of

deterioration since Lang had left; I saw them in their fleet

manoeuvres, in their gunnery practice and in their battalion

drill on shore, and took the keenest interest in it all, and sent

a report about it to Sir Robert Hart.

—

doing its little best after a few years of

deterioration since Lang had left; I saw them in their fleet

manoeuvres, in their gunnery practice and in their battalion

drill on shore, and took the keenest interest in it all, and sent

a report about it to Sir Robert Hart.

During the manoeuvres a Japanese man-of-war appeared

upon the scene, exchanged salutes, watched what was doing,

made no communication and then departed; a few months

later the two fleets fought.

Already there were rumours of Japanese aggression in Korea

— a place of doubtful suzerainty regarding China and Japan —

which might lead to war; so I considered — but only as a thing

of interest — the relative fighting strength of the two countries.

Quite obviously the matter would be settled on the sea; and

I concluded, from the meagre information which I had, that

the Chinese stood a reasonable chance.

The bombshell fell with about the same degree of notice as

in the Great War. A Chinese transport carrying troops to

Korea was sunk by a Japanese squadron; and the fat was in

the fire.

Let me tell how this affected me. I had often thought and

said how desirable it would be to have two lives — one for

adventure, in which case I would go a-whaling, and one for

getting on, with one's nose on the grindstone of service to one's

chief or to one's cause. And here rose an opportunity for a

combination of the two. When I thought of Woo and Tsao

and how they showed me round their battleship and filled me

with admiration for the detailed knowledge of their job that

they possessed, I could hardly think that I could be of any use;

but I thought of my report about the Chinese fleet. Could I

not serve a useful purpose by recording for our Admiralty the

facts of that great naval fight that must now come off? That

was the conscious factor which decided me to volunteer. It

need hardly be explained that to go fighting in this way is a

very different proposition to doing one's normal service for

one's country.

The one is duty, the other is adventure; it

is also a misdemeanour. The stimulus is essentially different in the two. In the case of the adventurer the stimulus may

be an appeal to help a cause; it may be mere self-advantage

in a gamble; or it may be some form of desperation, in which

any change — perhaps even the prospect of death — is welcome.

I have known cases of all three. But none of these affected

me so far as I am aware. I knew nothing of the justice of the

quarrel; I had been under fire and disliked it very much; I

was happy where I was. My one idea was to make a technical

report, as I saw but little chance of any one more competent

than myself for doing so being present. There was some

unselfishness in this, for I knew quite well that by a breach

of the Foreign Enlistment Act I should place myself beyond

the pale of any recognition of my service; and so it proved;

but anyhow, as things turned out, reporting took a very

secondary place in my activities.

I decided to volunteer. The question was how to do it.

Ask permission of Sir Robert Hart? No, not that, for it

would impose undue responsibility on him. So I sent the

message: ` If opportunity occurs, I intend to volunteer for

active service.' The answer came: ` Tyler transferred to

Tientsin.' The rest remained with me. At Tientsin I

received my first personal letter from the great I.G., as the

Inspector-General was called. In effect he said:' Your wish

is after my own heart; but do not forget that your risks will

be more than that of normal war. Your authorities may

imprison you for a breach of the Foreign Enlistment Act; the

Japanese will shoot you if they catch you; and you may be

murdered by the people that you serve.'

At Tientsin I dealt with

Detring and von Hanneken.  —

The appointment of the latter as Co-Admiral was needed, among

other things, to save Admiral Ting from summary decapitation,

in case of a reverse; for that is what, in accordance with

ancient practice, the Empress Dowager would order. A

soldier engineer to be an Admiral? That did not bother Li

Hung-chang, for Ting himself was a cavalry officer and made

no pretence of knowing anything about a ship. As for von

Hanneken, it is doubtful if any one else — say an English

admiral — could, in the circumstances, have better filled the

post. To complete this burlesque setting of the stage, I, a

Naval Reserve Sub-Lieutenant, was appointed Naval Adviser

and Secretary to von Hanneken; so there we were.

—

The appointment of the latter as Co-Admiral was needed, among

other things, to save Admiral Ting from summary decapitation,

in case of a reverse; for that is what, in accordance with

ancient practice, the Empress Dowager would order. A

soldier engineer to be an Admiral? That did not bother Li

Hung-chang, for Ting himself was a cavalry officer and made

no pretence of knowing anything about a ship. As for von

Hanneken, it is doubtful if any one else — say an English

admiral — could, in the circumstances, have better filled the

post. To complete this burlesque setting of the stage, I, a

Naval Reserve Sub-Lieutenant, was appointed Naval Adviser

and Secretary to von Hanneken; so there we were.

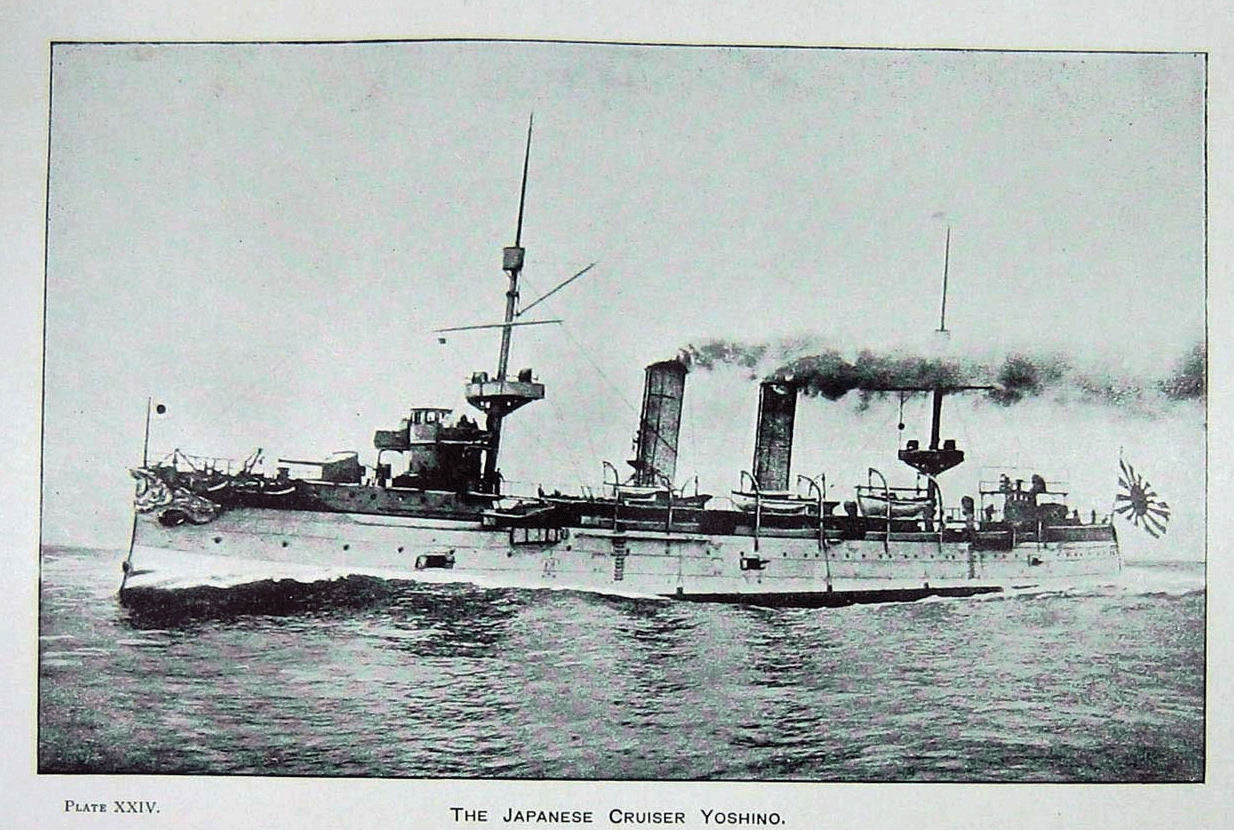

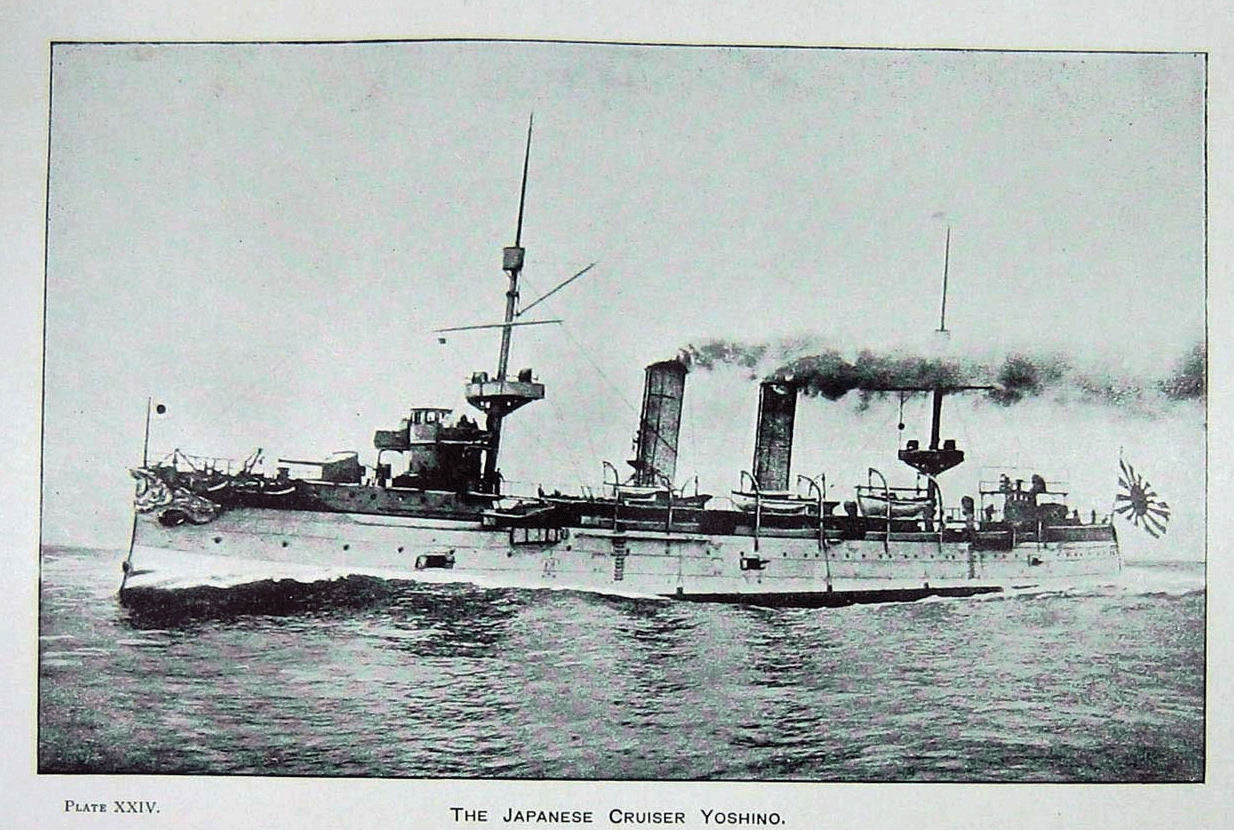

My own contribution to a discussion of the war with Detring

and von Hanneken was this: — Buy telegraphically that new

Chilian cruiser for delivery in our waters — I think she was the

Fifteenth of May — the fastest cruiser in the world. Pay any

price they ask for her, no haggling and no delay. Give me

command of her. Some of her officers will volunteer and I

will find others somehow. Chinese gunners, stokers and

deck hands will do for me. I will harry the enemy coast and

shipping. If we can delay fleet action until my ship is in

commission, all will, I think, be well; for then their first

thought will be to tackle me. They will detail the Yoshino

and other fast cruisers to watch the coaling ports; and thus

so much the better for our fleet. The enemy troops are bound

to win in Korea and invade China from her frontier, and so

give encouragement in that direction. In these circumstances

the Japanese will not be keen to stake their all on a fleet action;

and thus the situation will develop to our advantage; and,

if I am successful, they will be sorry that they ever went

to war.

Something of the sort had already been considered, they

said; but the idea now caught on. The Viceroy agreed. A

few days later the purchase was said to be completed, and I was

cock-a-hoop at this most gorgeous opportunity. My mind was

full of scheming about officers and coal; and a report for the

Admiralty became a very secondary thing.

A fortnight later came the shock. The Chilian price had

not included ammunition — or a reserve of it, I am not sure

which — and negotiations ceased. In this way is history made;

but had the Japanese to do with it in one way or the other?

It is more than likely.

Von Hanneken, a Prussian, was a fortification engineer and

had built the defences at Port Arthur and Weihaiwei — a fine

fellow and a fine character, though he showed some curious

traits in later life. He had been with the soldiers on the

transport Kowshing when she was sunk by the Japanese and

the drowning men were fired at in the water. He swam — I

am afraid to say how many miles — to an island, and so was

saved; he was quite a sportsman with his Iife.

He and I joined the fleet off Taku Bar and then proceeded

to Port Arthur, where a scrutiny of ammunition lists showed

for the first time the tragic fact that for the ten-inch guns of the

battleships there were only three big shell and that the smaller

practice ten-inch shell were also sadly short; for the other

ships there was a reasonable stock. A telegram was at once

sent to the Viceroy that the fate of China depended on the

arsenal working night and day at making shell; that the matter

was of such great urgency that he was begged to trust to no one

— not even the Director of the Arsenal — but to go himself and

see that it was done; but of course that was not done, and

some weeks later a transport brought some shell and a letter

from the Director: ` The four calibre shell could not be manufactured; of two and a half calibre shell we were now supplied

with so and so; that would complete the normal complement,

and that was all we could expect from him.'

Soon after we joined the fleet Iwas appointed Co-Commander

with Li Ting-sing. In my diary I grouse at the falsity of my

position — no authority, only advisory functions — and I grouse

at Li himself; but that was quite unjust. I had to earn confidence, and Li Ting-sing was always charming to me. Before

that appointment I had messed with a British ex-bluejacket

and a German engineer, but now Li, of his own accord, gave

up to me his comfortable quarters of a sitting-room and cabin.

Through many ups and downs of life for him in after years Li

and I stayed friends; he was not a strong character and he had

lost his grip over the men, but that was largely due to Liu

Poo-chin, the Commodore, who never supported him. So I

pottered along and did what I could, worked up the signal

system, the fleet organization — such as it was — and the complicated inwards of the ship; and after all that was quite enough

to do to start with. I was just a unit in the great organism of

a battleship trying to do my job; and, in between whiles,

wondering what was going to happen.

I read my diary of the war, my reports and other papers for

the first time since those days. It is instructive — to me — to

compare the facts recorded with what is in my memory. My

own doings are recorded only as incidental to what was going

on; personal experiences, however drastic, are barely touched

on and in some cases entirely ignored. Yes, my diary is quite

modest, for I was caught up in an organism of monstrous

complexity. A large battleship and how it works is quite

nicely complicated; but that is not what is meant here. Comparatively that was very simple. The complexity lay in a vast

muddle of diverse motives and ideals. Where there should

have been homogeneity of purpose, there was a monstrously

disordered epicyclic heterogeneity. In this machine — which

included not only the fleet but all that was cognate to it, from

the Viceroy to the Arsenal Director — the groups of wheels

revolved to no general purpose but only to their own. The

various groups engaged and disengaged when necessary, by

some process of give-and-take which caused each other the

least inconvenience. It was the antithesis of an ordered

regimen from the standpoint of efficiency; but it was disorder

curiously ordered, and — in peace time — worked without a

rattle, well greased with peculation, and with nepotism — that

scum from the high virtues of their ancient sages.

Is all this a kind of double-dutch? I will illustrate it by

one example. For the ten-inch guns on the two battleships

the fighting projectile was a powerful four calibre one; the

practice shell was two and a half calibre. Of the latter the

magazines contained a stock of sorts. Of the former the flagship possessed a solitary one and her sister ship a pair. Now

we may be sure that when the war broke out the Gunnery

Lieutenants — both were good men — were much concerned at

this and reminded the two Commodores; these presumably

told Ting, the Admiral, who in turn would requisition on the

arsenal; but when nothing happened no complaints were

made. To appeal to the Viceroy — whose son-in-law Chang

P'ei-Iun was Director of the Arsenal and, though it was not

known at the time, was at least flirting with the Japanese —

would be contrary to all Chinese practice; it would upset the

whole machine, such as it was. The chief villains of the piece

were three captains — Lin, Liu, and Fong; but not Ting the

Admiral. He stood on a pinnacle of fair fame — and responsibility for the sins of others.

As for the rest — Commanders, Lieutenants and Engineers

— they were just enmeshed in the machine. They would hardly

know the fact, for the condition was normal to their circumstances. Then there were the men — the seamen and the

stokers; fine stuff, mighty fine material, uncontaminated by

the moral disease of Chinese officialdom; similar stuff to what

the Golden Horde was made of when it swept over Eastern

Europe. And in between were the warrant officers, partly

one thing and partly the other.

The head of aII this business was Li Hung-chang the Viceroy,

who next to

Li Lien-ying,  —

the palace eunuch, was the right

hand of the

Empress Dowager.

—

the palace eunuch, was the right

hand of the

Empress Dowager.  —

The Viceroy was a diplomat

of world-wide fame; but to his countrymen — before the war

— he was chiefly reputed as a great military and naval organizer.

—

The Viceroy was a diplomat

of world-wide fame; but to his countrymen — before the war

— he was chiefly reputed as a great military and naval organizer.

He was not nor could he be that; for the corruption, peculation and nepotism which infested his organizations had their

fountain-head in himself, and to an extent which was exceptional even for a Chinese official. He was himself enmeshed

in the national machine of organized inefficiency; to him also

it was a normal condition, and any other, had it been indicated,

would have been incomprehensible to him. Yet with all this

he was without a doubt a fervent patriot; and there is an

example of a Chinese puzzle.

But to me the greatest puzzle of the war was this: at the

time the great military and naval review of 1893 was held,

war already threatened. A year or so before, the Viceroy, at

the instance of von Hanneken, had approved the ordering of

a large supply of heavy shell for the battleships. That order

was not executed owing to the obstruction of the notorious

Chang P'ei-lun.  —

But on the occasion of that review with the

threat of war in the air, was the Viceroy reminded of the

shortage? If not by Admiral Ting, why not by von Hanneken or Detring, who were present?

—

But on the occasion of that review with the

threat of war in the air, was the Viceroy reminded of the

shortage? If not by Admiral Ting, why not by von Hanneken or Detring, who were present?

I must pass over particulars of the origin of the war; but

briefly China and Japan exercised a joint suzerainty over

Korea, and Japan was determined to push China out and later

to annex the peninsula. It was Japan that was the aggressor

both in the circumstances that Ied to war and in the first

belligerent act. Now the Viceroy's game was merely bluff,

not genuine defence; his army and his navy were the equivalent of the terrifying masks which Eastern medieval soldiers

wore to scare their enemy. He knew that if it came to actual

blows he would stand but little chance; but he carried on his

bluff so far that withdrawal was impossible, and the Empress

Dowager urged him on — probably much against his will. And

Japan ` saw him,' as they say in poker.

Perhaps next to Li Hung-chang and the Imperial entourage

came Detring as a factor in the war. He was a German and

Customs Commissioner at Tientsin; there he had consolidated

himself as Li's adviser and thus become partly independent of

Sir Robert Hart, who presumably did not like it. Detring

thought he looked like Bismarck, and doubtless the fact affected

him, for rather than looking like what we are, the tendency

is to become what we think we look like; but in his case the

looking-glass belied him. He adopted a Bismarckian manner

and had a certain grandeur of conception; but obviously in

such a matter as war he lacked the elements of judgment and

execution, and played with it as a boy might play at being a

Red Indian. He1 had accompanied the Viceroy on the review,

when war was in the air. A schoolboy would at once have

thought of ammunition; yet that elementary need was unattended to.

Let me revert now to that diary of mine. Plainly I did not

know the picture I have sketched. I just floundered in the

dark. The diary refers often to the difficulties that I found,

to the wish I could do more; but I also took it all for granted

more or less; and it was just as well I did so. At first as

Co-Commander I had no authority at aIl, but later it increased

and towards the end became more or less effective. From the

beginning I took occasional initiatives outside my job; in

respect to fighting and executive work I was perhaps the only

one in a position to do so, and I had a few adventures.

1 — Regarding what I say about Detring, Sir Francis Aglen, the late

Inspector-General of Customs, writes: — ` Detring's swans were nearly

always geese, but in many respects he was a big-minded man. If he erred

in believing in the Chinese bubble he was in good company, for at the beginning Sir Robert Hart himself thought that China would win. I have no doubt that such advice as Detring gave to Li Hung-chang was sound enough;

and so awe-inspiring was Li's position that Detring was the only man who

dared tell him unpalatable truths. But Detring had no sort of power in

connection with naval or arsenal affairs and I do not think he can be saddled

with responsibility for shortage of shell.'

And Dr. H. B. Morse, the historian of China, writes: — ` What you say

about Detring is about right. He had extraordinary diplomatic ability

but enormous vanity. But he had nothing to do with ammunition; in

fact if he had tried to interfere in the matter he would have stirred a hornets

nest and destroyed his usefulness.'

Neither of these views affects for me the picture I have drawn.

These things bulk largely in my memory, but they did not bulk

largely in my mind when they occurred, nor in the minds of

others. I was not a central figure. Yes, I was quite modest

in that diary, but all the same I find a letter in which I

vigorously attack the Times correspondent for giving others

credit for what I had done.

There were five foreigners in the fleet Left over from the

time of Captain Lang. In the flagship was Nicholls, an

ex-British bluejacket, sound as a bell, and Albrecht, a German

engineer. In the sister battleship Chen Yuen was Heckman,

the German gunnery expert, a most capable person; also

Philo M`Giffin, an American navigation teacher, who was not

quite all there. In another vessel was Purvis, an English

engineer, a great favourite with us all.

Weihaiwei was our principal headquarters, and there we

foreigners and the Chinese Captains gathered in the Club and

discussed the question of fleet formation, of ramming and close

quarters. There were yarns of the cruise to find the enemy

which took place before I joined, and how they met a squadron

in the dark and each fled from the other. There were whispers

that the Commodore was most anxious not to meet the enemy.

There was a young Captain, who had a lot to say about what

he was going to do, and it was he who fled incontinently at the

beginning of the Yalu battle.

The Admiral held a council of war and it was decided to

fight in line ahead of sections — a section being mostly two sister

ships in quarter line. I was rather disappointed at not being

told to come, though I had no right to expect it. I wished

I had a life-saving waistcoat, and I obtained a hypodermic

syringe and a tube or two of morphia.

This is the place — before I come to my adventures — to

explain about a feature of this book. There is, among a

certain class of us, a convention forming the basis of our social

intercourse, that we must not talk about ourselves except it be

of a hand at bridge, a game of golf or such like; we must

never be earnest or enthusiastic except about such subjects;

and there are quite a lot of other things we may not do. This

convention — whose genesis lies in the inhibitions of our schoolboy days — serves a very useful purpose. It scotches the

tendency to mental swank; it produces a plane of intercourse

in which all enjoy equality, and so it makes our English social

ways — for those within the ring fence — the pleasantest to the

average mind in all the world.

But to carry that convention into books — though it may

depend upon the book — is purposeless, for on the one hand if

a writer bores us we can sling his book away, and on the other

a human document is to most of us a thing of interest.

So in this book I discard that limitation and express myself

as freely as I care to.

#

— of the northern province Chihli — the most powerful

satrap of that time — who owned a fleet. Nanking and Canton

also had their fleets, but their craft were obsolete. Li Hung-

chang's was very different. His ships were up to date — two

battleships with ten-inch guns, armoured cruisers, light

cruisers and torpedo boats — and he had engaged an English

naval officer — Captain Lang — to train the officers and crews.

— of the northern province Chihli — the most powerful

satrap of that time — who owned a fleet. Nanking and Canton

also had their fleets, but their craft were obsolete. Li Hung-

chang's was very different. His ships were up to date — two

battleships with ten-inch guns, armoured cruisers, light

cruisers and torpedo boats — and he had engaged an English

naval officer — Captain Lang — to train the officers and crews.

— was the Admiral; Lang also held that rank,

but in an ambiguous Chinese form which might mean anything

from the second in command to an adviser with the rank of

admiral. Lang believed it was the former, so, when Admiral

Ting was called to an audience at Peking, he claimed to take

his place; but Liu Poo-chin, the senior Commodore, maintained that Lang was only an adviser and that the post was his.

— was the Admiral; Lang also held that rank,

but in an ambiguous Chinese form which might mean anything

from the second in command to an adviser with the rank of

admiral. Lang believed it was the former, so, when Admiral

Ting was called to an audience at Peking, he claimed to take

his place; but Liu Poo-chin, the senior Commodore, maintained that Lang was only an adviser and that the post was his. —

doing its little best after a few years of

deterioration since Lang had left; I saw them in their fleet

manoeuvres, in their gunnery practice and in their battalion

drill on shore, and took the keenest interest in it all, and sent

a report about it to Sir Robert Hart.

—

doing its little best after a few years of

deterioration since Lang had left; I saw them in their fleet

manoeuvres, in their gunnery practice and in their battalion

drill on shore, and took the keenest interest in it all, and sent

a report about it to Sir Robert Hart. —

The appointment of the latter as Co-Admiral was needed, among

other things, to save Admiral Ting from summary decapitation,

in case of a reverse; for that is what, in accordance with

ancient practice, the Empress Dowager would order. A

soldier engineer to be an Admiral? That did not bother Li

Hung-chang, for Ting himself was a cavalry officer and made

no pretence of knowing anything about a ship. As for von

Hanneken, it is doubtful if any one else — say an English

admiral — could, in the circumstances, have better filled the

post. To complete this burlesque setting of the stage, I, a

Naval Reserve Sub-Lieutenant, was appointed Naval Adviser

and Secretary to von Hanneken; so there we were.

—

The appointment of the latter as Co-Admiral was needed, among

other things, to save Admiral Ting from summary decapitation,

in case of a reverse; for that is what, in accordance with

ancient practice, the Empress Dowager would order. A

soldier engineer to be an Admiral? That did not bother Li

Hung-chang, for Ting himself was a cavalry officer and made

no pretence of knowing anything about a ship. As for von

Hanneken, it is doubtful if any one else — say an English

admiral — could, in the circumstances, have better filled the

post. To complete this burlesque setting of the stage, I, a

Naval Reserve Sub-Lieutenant, was appointed Naval Adviser

and Secretary to von Hanneken; so there we were.

—

the palace eunuch, was the right

hand of the

Empress Dowager.

—

the palace eunuch, was the right

hand of the

Empress Dowager.  —

The Viceroy was a diplomat

of world-wide fame; but to his countrymen — before the war

— he was chiefly reputed as a great military and naval organizer.

—

The Viceroy was a diplomat

of world-wide fame; but to his countrymen — before the war

— he was chiefly reputed as a great military and naval organizer.  —

But on the occasion of that review with the

threat of war in the air, was the Viceroy reminded of the

shortage? If not by Admiral Ting, why not by von Hanneken or Detring, who were present?

—

But on the occasion of that review with the

threat of war in the air, was the Viceroy reminded of the

shortage? If not by Admiral Ting, why not by von Hanneken or Detring, who were present?