3. The Capitulation

Admiral Ito's reply to the capitulating letter, falsely purporting to come from Ting, was a model of chivalrous courtesy.

It was written in English, and dated the 12th February 1895

"I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter

and to inform you that I accept the proposal which you have

made to me. Accordingly I shall take possession to-morrow

of all your ships, forts and other materials of war, which are

left in your hands. As to the honours and other minor

conditions, I shall be glad to make arrangements with you

to-morrow at the time when I shall receive a decisive answer

to this my present letter. When the above-mentioned materials

of war have been delivered up to me, I shall be willing to make

one of my ships conduct the persons mentioned in your letter,

including yourself, to a place convenient to both parties in

perfect security.

... But were I to state to you my personal views and feelings,

I would beckon you, as I had done so in my last letter, to come

over to our side and wait in my country until the termination

of the present war. Not only for your own safety but also for

the future interests of your country I consider it far more

preferable that you would render yourself to my country where

you are sure to be treated with care and attention.

` However, if it be your intention to regain your country,

I leave it entirely to your choice.

` As regards your desire to make the Admiral Commander-

in-Chief of the British fleet act as guarantee on your behalf,

I deem it unnecessary. It is on your military honour that I

place my confidence.

In conclusion let me inform you that I shall be waiting

for your answer to my present letter till 10 o'clock to-morrow

morning.'

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weihaiwei_surrender.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weihaiwei_surrender.jpg

The expression ` Come over to our side ' obviously merely

meant that Ting should on capitulation take refuge with

Ito in order to save his head and his services to his country

for the future. I have no knowledge what answer was sent

to this, but my diary contains a copy of a second letter

from Admiral Ito dated the 13th February and addressed

to ` The Officer representing the Chinese Fleet,' which

ended:-

[...]

` In my last letter to the lamented Admiral Ting it was said

as to the honours and other minor considerations, I shall be

glad to make arrangements with you to-morrow, and now that

he is dead those minor considerations have to be arranged

with somebody who can deal with us in his stead. It is my

express wish that the said officer, who is to come to this our

flagship for the above purpose, be a Chinese — not a foreign —

officer, and be it understood that I am willing to receive him

with honour.'

These letters give me cause for thought. They are manifestations of the highest form of chivalrous sentiment. Ting,

of course, was a personal friend of Ito, but that should not

detract in any way from one's admiration for the behaviour

of that gallant nation on this occasion. Yet, in my later life,

no one passed more vigorous criticism and condemnation on

their policy in China than myself.

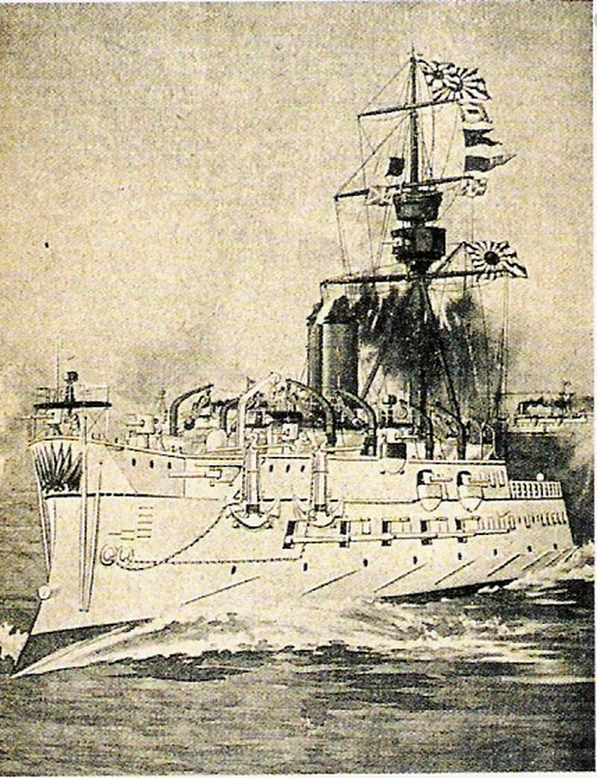

On the 16th two Japanese vessels entered and anchored

well to the southward; then a torpedo boat came with instructions that all foreign officers should proceed at once on

board the Matsushima.

Kirk and I considered this. We

anticipated that foreigners would be treated as mere adventurers and with some minor indignities, for, with Kirk's

exception, we could hardly expect otherwise. The others

would not feel it in the same degree that we should, so we

decided not to go and went to the hill-top to avoid being

taken off.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_cruiser_Matsushima

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_cruiser_Matsushima

The next day the Japanese fleet came in by the Western

Entrance, and as we watched the scene from some vantage

point on the road, a party of Japanese officers approached

us. I understood they were members of Admiral Ito's

staff and perhaps included Togo. We mutually saluted

and a conversation not recorded, but clearly remembered,

ensued:-

` You are Captain Tyler and you are Dr. Kirk? It is a nice

view you have here '; and I replied, with a movement of my

hand to the entering fleet, ` Yes, and a very interesting one

historically.' The officer smiled and nodded acquiescence,

then thought a bit and said: ' You two gentlemen were not

on board the Matsushima yesterday. I presume I can consider

your parole as given? ' — ` Yes, please,' and the party saluted

and passed on. Such very perfect manners !

There is not much more to tell of Weihaiwei. We were

given the Kwangchi — an old corvette — to take us to Chefoo.

Such gear as we could carry, or get carried, we put on board.

Small parties of Japanese, in charge of officers, were roaming

around, and some were quietly and in an orderly manner

looting those European houses already deserted by their

owners . At no time, says the diary, did I experience the

slightest rudeness or roughness from them.

So we reached Chefoo, and for us the war was over, though

there were still fag-ends of it to be dealt with by me. My

diary is full of details — of my relations with M`Clure; of the

gunners and their interests; of our wounded in the hospital.

Says the diary: ` Went out with Kirk to the hospital to help

him cut off an arm.'

Then Tientsin, where I was very well received by von

Hanneken, Detring and the community. I was asked if I

wished to see the Viceroy. I could see no useful purpose

in doing so. There was nothing I could tell him at this stage

that would not better be left unsaid. A settlement of the

claims of the foreign officers was placed in my hands, an onerous

and disagreeable task which left me in bitter enmity with

Lo Feng-loh, the Naval Secretary, and made me wonder what

effect that enmity might have on my future.

Now for something of the personnel with whom I served.

Of Ting Ju-chang — the Admiral — I have said enough to show

my admiration and devotion, an admiration shared by all who

knew him; but I will add this extract from the diary: —

` He

has, since the attack on this place was made, always been in

the place of most danger. When we bombarded the South

forts he was always on the bridge, while the Commodore was

slinking in the conning-tower. He was, of course, on board

when the Ting Yuen was torpedoed. Since then, when there

was any fighting, he has always been in the Ching Yuen in the

foremost place; and to-day he was on board of her when she

was sunk.' Also I add this little story: —

A foreign officer

posed on somewhat meagre grounds as an expert in torpedo

work, and was detailed to inspect torpedo boats. Fiddling

about with a bow tube, when the boat was under way, he

accidentally released the torpedo, which, sliding half-way out,

was bent and ruined by the pressure of the water. Ting had

the officer before him and said: ` The loss of a torpedo does

not matter much, for unfortunately I see no chance of using

them; but what I do not like about this affair is your pretence

to be an expert. Here am I Admiral of the Fleet. Do I

pretend? Do I assume to know anything about a ship or

navigation? You know I do not; so take an example from

me and pretend no more.'

The rich timbre of Kirk's brogue still echoes in my ears —

the most genial person I have ever known and the very best

companion. He laughed and whistled as he cut and sawed

those arms and legs, and, in response, even the patient sometimes smiled — and I repeat we had no anaesthetics. We were

exactly complementary, I think. What I lacked he had, and

vice versa; so in later days we could go a houseboat trip

together and never bore each other.

Old Howard was engineer in charge of the workshops. Of

the shore staff only he and Kirk and Schnell stuck to the

Chinese cause. He disapproved of me because I wore uniform;

it had not been done since the time of Captain Lang; we were

all mere advisers and my attempt to be something different was

just foolishness. I am glad that towards the end he unbent to

me, for I had a great regard for him; one could not have

anything else. He was so crippled with rheumatism that often

he could not walk, and he must have been more or less constantly in pain; but he never gave in; he was carried to his

shops and superintended from his chair. When the guns on

Itau Island were damaged, he was taken there in a litter and

his boat was under heavy fire on the way. At the time of

the beginning of the siege and the general exodus, I told

Howard I thought he ought to go; he retorted by telling

me that I ought to go to hell. A very gallant man was

Howard.

Thomas, Clarkeson and Walpole were ex-bluejackets from

the Customs service and Mellows another from the Shanghai

police. My report says: ` The Itau garrison came over to

Liukungtao to-day, including the gunners Thomas, Walpole

and Clarkeson. The behaviour of these men has been

splendid . . . . Not only their daring, but their quietness,

sobriety, and unassuming manner point them out as exceptional men. Mellows, the gunner of the Ting Yuen, is

included in this appreciation.'

Basse — a Prussian and a great friend of mine — had been my

shipmate in the Customs cruisers, and when I volunteered

he followed suit; but he joined up too late to be in the Yalu

battle. At the beginning of the siege of Weihaiwei he was on

a torpedo boat that was run down by a cruiser; fearing an

explosion of the boiler, he jumped overboard, got mixed up

with the propellers, was miraculously not killed but was badly

injured for a time. He wished to stay, but I pulled strings

with the Admiral and he was sent away. I mention Basse

because, although his venture seemed so great a failure, it led

him eventually to an extraordinary career; and while, so far, I

had been the leader of the two, it was he who later exercised an

influence on my life that was greater than that of any other

man.

And now about M'Clure. It will be seen later that I let

pass an opportunity to write a history of the naval war because

in doing so I should be unable to avoid the truth about him.

Thirty years and more have now passed; he was a public

character — to however small a public — and in a sense he was

a minor character in history. There were those four British

bluejackets in that serio-comedy, who played their various

parts so perfectly in every way; and there were others who

did their best to play the game. Are they to go entirely unsung,

while that gay old sportsman's memory scoops in all the little

credit with his comic part — for that is what it comes to? I

could not tell the story merely for the sake of telling it — not

even for its humour. But it is involved with what happened

at Weihaiwei; for if Ting had had a backing such as von

Hanneken, for example, could have given him, the siege of

Weihaiwei might have gone down to history as a minor epic.

It is not pleasant to feel that M`Clure's death some years ago

— now makes it possible for me to speak, yet so, in such cases,

it must always be.1

1 — ' I have a letter from the late Captain W. M'Clure, a nephew of the

Admiral,' in which he says that he knew his uncle's way — he was out in

China at the time; I was not to spoil my book out of consideration for

his family. But he pointed out that his uncle was a great old sportsman,

and that it could be claimed that he saved the Chinese Admiral's head; so

would I let him down as easily as possible. A very charming letter!

The stress and strain caused him to revert to drink — of

course not all the time, but particularly at moments of crises

in the siege — when decisions were most needed. I will not

say how much or when and how, and all I did about it. Apart

from stress and strain, the appointment as Co-Admiral went

to the head of this old tug-boat skipper. The sword, the

uniform, the piping of the side, the bugled Admiral's salute

were as strong wine to him; he lived in a glamour of this

miraculous thing that had happened to him. He seemed quite

happy and pleased with himself — never a word of remorse or

shame for what he did or did not do, — and all the time he

beamed with good nature; even to me — against whom he had

an unforgivable grievance — his manner was never anything but

cordial. To say that he had no evil or meanness in him does not

go nearly far enough. He was a dear old soul in every way, apart

from that one failing, the manifestations of which, however,

were tragically and comically shocking; he was plucky enough

and stood fire with the best of us. In spite of his grievance

against me, I never heard of his accusing me of anything worse

than insubordination and impertinence — the latter a rather

curious touch. One feels sorry for any one in trouble and

unhappy; but in that sense there was no occasion to feel sorry

for M'Clure. He was a serio-comic tragedy; and the more

one sees the comic side, the better for his memory.

His tug-boat was at Taku, the seaport of Tientsin. Cooper,

the Mate, had orders to have steam for proceeding to Weihaiwei.

M'Clure arrived; he had not yet donned his uniform, of

course. ` Well, John,' said Cooper in his customary manner

with his Captain, ' what 's the news? ' John drew himself up

with such dignity as he could: ' Allow me to inform you,

Captain Cooper,' and he paused to let this new title for the

Mate soak in, ` that evidently you are unaware whom you are

addressing. Let me make you acquainted with the fact that

I am the Admiral of the Chinese fleet; this is my despatch

vessel; you are, for the time being, my Flag-Captain. Get

off my quarterdeck and get the vessel under way.'

There came the landing of the Japanese at the Promontory

and a decision to be taken; then the capture of our South forts

and bold action needed; and the little use M'Clure might

have been he was not. It was then I spoke to Ting about it

and asked him to get Kirk to put M`Clure on the sick-list; but

it was not done. So I spoke to him myself, and warned him

that if he did not at once pull himself together, I should report

him to Tientsin. I spoke respectfully, with lots of honorifics

— ` Sir ' and ' Admiral ' — and the next day sent my cypher

telegram to beg for his removal; I showed him that telegram

as soon as he could read it. Then I wrote my justification for

the extraordinary step I had taken, and sent it to von Hanneken

with a tender of my resignation. Ting knew and privately

approved this step, and he came to my cabin, told me he had

tried and failed to get M` Cure to go quietly to Chefoo, and

asked what I recommended. So we sent for Kirk and got

him to put the Co-Admiral on the sick-list; he made no

difficulty about going on shore, where I placed my house at

his disposal; and there he pulled himself together — until the

next time.

I have kept the Chinese naval officer to the last because

there is so much to say about him. With all his faults I

liked him; those faults were not his own but those of

circumstances.

I continued to be associated with them, more or less, for all

my life in China. I think now of Woo and Tsao in their

retirement at Peking when I visited them one day. Woo,

the former Flag-Lieutenant; Tsao, the former gunnery officer

of the Chen Yuen; both then Admirals retired, great friends

and porcelain fiends. I lunched at first with Tsao and saw his

wonderful collection. ` Woo tells me he also goes in for

porcelain.' — ` That 's exactly what he does,' said Tsao, ` he

goes in for it. He does not collect; he just sweeps the damn

stuff up. It is quite useless for him; he has not got the eye

for colour, the touch for texture nor that fifth sense which

enables me to tell a fake with certainty. His stuff is rubbish;

but you will see for yourself.' The next day I lunched with

Woo and saw his collection, which appeared to me at least as

good as Tsao's, to which I then referred. ` I suppose you did

not notice that most of his things are clever fakes. It is very

pathetic to see that poor blighter wasting all his substance on

collecting rubbish; but he refuses to believe that he has no

judgment.' So these two good fellows — two of the very best —

had found a pleasant occupation. Observe their language,

their vernacular; it is not a bit exaggerated. Their mental

adaptability in that respect was quite extraordinary. On one

occasion in the war there was reference to some unusual waste

of money, and Woo the Flag-Lieutenant walked away whistling

` Pop goes the weasel.'

The raw human material of China for any purpose is at least

as good as that of any other country, though some of its

qualities are only latent and potential. I have seen them spring

to life among the common men; but only rarely among the

officers. Yet the officers are the same material — the same

breed — as their men; as much, say, as in France, and more so

than in England. Obviously, then, what they lack is not due

to any inherent characteristics but to influences that infect

their official status.

Ideals are common to all of us; common, too, is our blindness to their defects. They become transfigured to us, as

the gilded and tinsel-covered image is transfigured to the

worshipper; they deteriorate in the course of years, go rotten

or get out of date, and still we blindly worship them. We saw

that in the German Empire; if we open our eyes we can see

it to-day in our own country; but in these two cases the cults

not only did not undermine virility, they supported it. It is

China's vast misfortune that her cult tends to emasculate

every one who rises above the grade of coolie.

The influence of ideals is propagated through the medium

of self-respect. It is a curious business, this self-respect; it

has little to do with virtue; it is attained by conformity to a

code. In Jew Süss it was the foul debaucheries of Duke Carl

that pandered to his self-respect. In our grandfathers' time

the man who missed the chance to ruin a country girl was

thought a fool; and to-day the condition is merely modified.

The woman beckons, barely knowing what she is doing; the

man is scared, perhaps, and knows it is not worth the candle;

but his manhood has a claim; he has to satisfy his self-respect.

Yes, self-respect is involved in nearly all the evils of the world

— from the exercise of graft to the embroilment of the world

in a long and bloody war. It has involved also many other

things, and among these, in Western countries, are fortitude

and physical endurance. In Western countries, but not in

China, for if you seek those qualities in Chinese leaders, you

have to look for them among the Canton pirates and the

Northern brigands; and that, of course, is why Chang Tso-lin

— an ex-brigand — was for a time China's greatest man.

China is over-cultured. Under her culture, elemental virtues

have become diverted and transmuted. One must disregard

the mere moment of our lifetime in the history of China; one

must think in millenaries — in millenaries of desire for that

classical culture which became the only road to greatness.

The most significant stigma of that obsession of desire is to be

seen in the Chinese hand — those delicately fine fingers, by

which a single sweep of the brush can paint a bamboo leaf with

all its lights and shades; and the touch-spots on those fingertips are so developed that the charm of jade lies not only in its

colour, but in the feel of its varying texture.

But factors in character are in general quantitative. They

may be diverted or transmuted, but they are not annulled.

There is daring in the coolie when he is led — he has endurance

and fortitude. The same qualities are necessarily in the

higher classes, but there they take another form — the daring

of commercial and political scheming, in which they run risks

enough. But daring of that kind must centre in the few. It

is only the few who have a chance to exercise it to any considerable degree; and so the rest — the great bulk of them — are

mere servitors in the furthering of the ambition of their

masters. They never really serve a cause — only their master's

interests or their own. It is a miserably vicious circle of cause

and effect. It is no one's fault. They are caught in the

machine and held there; if one of them attempted to follow the

principle, ` I will do my duty without regard to praise or blame,'

he would inevitably go under.

Yet in this matter it is easy to misjudge. Our system —

that of the West generally — is individualism; that of the East

is collectivism. And who can say that one is right and the

other wrong? China's collectivism, with the peculiar doctrine

of her old sages about inter-related duties of persons, has

preserved her as sole survivor of the ancient civilizations. It

was a system that aimed at the permanence of the state — not as

in the cases of other civilizations, at the permanence of a

dynasty. It has obvious and outstanding virtues; and for a

state that was dominant — as China was — in the only world she

knew, even the development of the characteristics which

manifested themselves in those delicate and sensitive fingers,

in the shedding of the cruder virtues, in the glorification of

philosophy and in the leaving of defence to a lower grade of

persons, had its points; for, if all the world would do the same,

with some regard for modern ideas, it might be a better place

to live in. But, of course, the world the Chinese knew — on

the condition of which the virtue of that cult was based — was

not the real world. Thus were the Romans, in their supposed

impregnability, deceived. And so also on China, from North

and East and South, descended what to her were barbarians,

but with this difference from the experience of Rome. Her

enemies had not only the rude and crude quality of valour, but

also arts and crafts of warfare beyond conception; and,

against this combination, China stood helpless.

But the long-drawn civil war will tend towards making

endurance and fortitude fashionable qualities; for, in spite

of buying and selling of armies, treachery and double treachery

and all those features which make Chinese civil war so burlesque,

there really has been genuine fighting now and then, and valour

will appreciate in credit.

The view here offered is merely an impression. It can only

represent a portion of the picture, as I see it — that portion which

is purely Chinese in character. But there is another part —

a very striking one — drastically affecting the picture as a whole.

That part is the incidence of Western cults and knowledge.

Think first of what happened in Japan in that respect. That

state was a compact entity; the Emperor's writ ran throughout

the land. It was organized — above all it was organized. It

has not been mere cleverness, nor bravery, that has made

that country what she is today; it has been organization.

So when the West impinged on her, she put what it had to tell

her in a sieve, and sifted out the parts useful to her — for

example, all the sciences and the art of war. She looked at

what was left behind — varying ideals of different Western

states, religions of many and antagonistic kinds, art which

struck her as unimaginative; and most of it she threw in the

dustbin. But what she sifted out she absorbed into her body

politic as a lump of sugar is absorbed in a glass of water.

But in China Western knowledge and Western cults descended on her unguided and uncontrolled. There was no

winnowing of it; there was no sifting of what was good for

China from what was bad. There was no thought of doing so

on the part of those who brought it — was it not Western and,

therefore, good? And on the part of China there was no means

to do so. So in poured science, history taught from different

standpoints, liberty, freedom, individualism, the virtue of

republics and of party government, and missionaries galore,

from Roman Catholics to Seventh Day Adventists and even

Holy Shakers; and young China, encouraged by its parents

and eager for advance, lapped up the lot. So there was this

new muddle superimposed upon the old; and with the combination of the two there set in a rot, a disintegration, on the

fringe of China — so far only on its fringe — of those factors,

of that matrix, which through all the ages had bound together

the Chinese people. What was good in that old cult of theirs

they tended to throw away; while the scum of it — nepotism,

corruption and intrigue — they stuck to. What is good in

Western ideals they can seldom give effect to; while what has

no inherent virtue, but is an accident of our development — for

example government by parties — they put up on a pedestal.

And until quite recently — perhaps even now 1 — the forces

of philanthropy in Europe and America were busy with this

cruel propagation, turning out students by the thousand every

year; students with half-hatched notions, with ideas which

their mental stomachs are quite incapable of absorbing; and

for whom positions cannot possibly be found.

1 — I am told, however, that the China educationalist of to-day has a better

realization of what the country needs.

There has been no assimilation of Western knowledge into

China's body politic. The simile here is not the lump of

sugar in the glass of water as in Japan's case; here it is that

of blobs of oil floating on the water and tending to go putrid.

One should not blame the missionaries for this. Their part

in it has been comparatively small; and whether that part has

been right or wrong, good or bad, it was one that had to be.

So let it stand at that. But with the educationalists the matter

is very different. They should have known the forces they

were playing with. It is quite true they were in good company. The foreign Ministers in China put their imprimatur

on what they did, and foreign Chambers of Commerce gave

them money; but these looked on them as experts; they

approved and gave as to a church.

I am reminded of a story. An eminent philanthropist at

Shanghai — an American — lunched with me alone one Sunday.

He asked me had I been to church and what was the sermon's

text? I replied that my deafness usually prevented me from

hearing a sermon, but that on this occasion I had got the pith

of the text, and it amounted to this: You can give all your goods

to the poor and you can frizzle at the stake; but you will go

to hell just the same, unless you love your neighbour. At

these words my guest got up and walked about the room with

his fingers in his hair, and I feared my slangy way had hurt his

feelings. ' You will, I hope, excuse my agitation, when I

tell you of the cause. That canned sermon of yours got me on

the raw; its text always does. You see, I have been a propagandist all my life. My father was before me. I have written,

and lectured, and led in propaganda. I am anti-nicotine, and

anti-drink, anti-nearly everything that most men like; but that

text always gives me cause to wonder whether I do these things

because I love my neighbour or because I just like doing them.'

It is a pity that the China educationalist did not ask themselves that question years ago, but they and their other confrères

did much worse than not ask themselves; they built up an influence which prevented others asking. Their tentacles were

widely spread — over parliament and the State, over the publicity

organs of the country; so that an independent publicist could

not get a hearing. There is graft in other places than Chicago.1

Here again I give a broad impression of what I see. Exaggerated? Perhaps, but, as in some modern pictures,

exaggerated by masses of lights and shades and absence of all

detail; yet presenting truth.

1 — This subject is dealt with further — in Appendix A.

#

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weihaiwei_surrender.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weihaiwei_surrender.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_cruiser_Matsushima

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_cruiser_Matsushima