1. Its Birth

[click]

[click]

THERE are several backgrounds to the picture of my life in

China that now began; one is the story of Shanghai; another

is that of the Customs Service. If I tell the latter first it will

help towards the former. A full story of either would be a

matter of historical research running into many volumes. All

I can do is to give an impression of those features which are

most salient to me, and in the case of the Customs those

features are its birth and early growth.

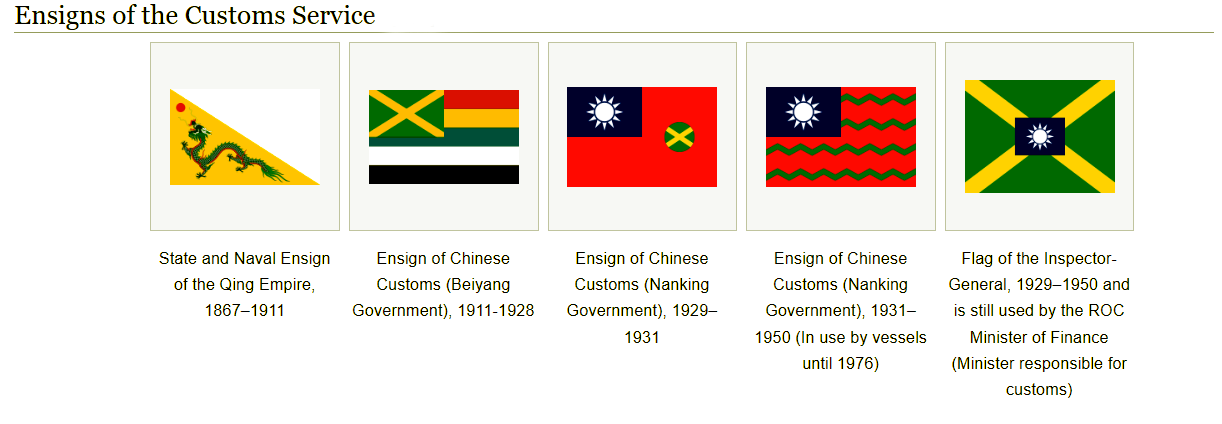

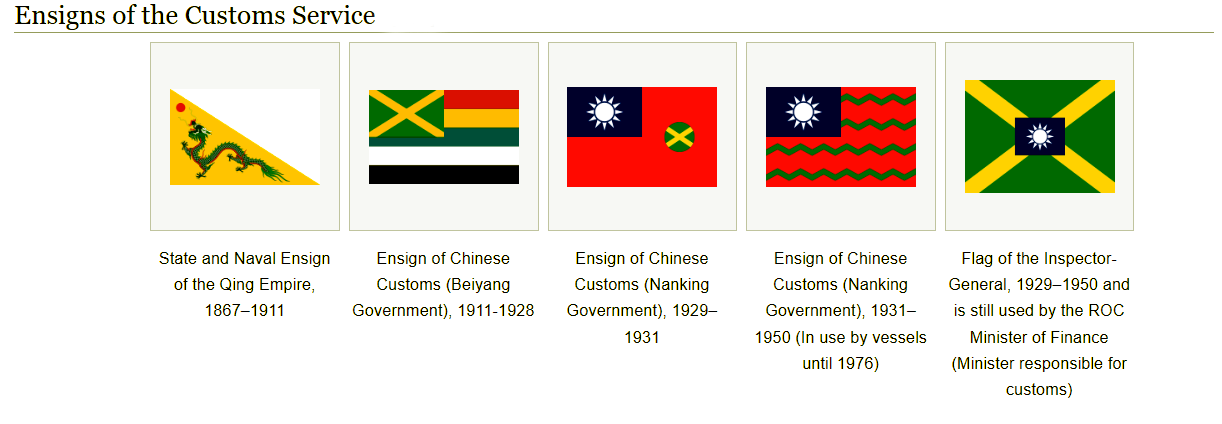

In 1853 the Taiping Rebellion against the Manchu dynasty

was in progress, and the rebels dominated more than half the

country. In that year the walled city of Shanghai was captured

by an independent rebel faction; they held the city only, and

the imperial troops invested it. Down river from the city wall

lay the foreign settlements, which with the harbour were,

owing to the fighting going on, declared neutral by the three

treaty powers, Great Britain, France and America, and which

the foreigners were determined to defend.

With the Government offices in the hands of rebels, with the

imperial officials in the settlement as refugees and prohibited

by the treaty powers from acting either there or on the river,

the collection of the Customs imposts on foreign trade due to

the Imperial Government became hung up. For certain

reasons this stoppage of a normal function caused an embarrassing confusion. The situation was eventually met by an

arrangement under which three delegates of the treaty powers

superintended the collection; and, in effect, that was the

beginning of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service.

The result of the honest and efficient administration of these

delegates was such that in 1858 the Imperial Government

extended the system of its own free will to all the treaty ports,

and placed it in charge of Mr. Horatio Nelson Lay, who had

been the British delegate at Shanghai, and who was now lent

from the Consular Service. It should be noted that at the

time of his appointment there was a lull in the war which for

the past three years England had waged against China; but

it soon broke out again, and two years later — in 1860 — Peking

was occupied and the Summer Palace destroyed as a punishment for a monstrous outrage by the Chinese Government.

Yet Lay maintained his post; and in 1861 when in connection

with the payment of a war indemnity it became necessary for

the Chinese to organize a consolidated Customs Service as an

imperial instead of a provincial affair — which it had hitherto

been — Lay was appointed its Inspector-General. His appointments were the more extraordinary inasmuch as when —

immediately before he got the first of them — he was acting as

interpreter to Lord Elgin in the peace negotiations at Tientsin,

he treated Chinese high officials with notorious truculence and

indignity. It was doubtless his ability and his honesty in

raking in dollars for the Chinese authorities and his exceptional

knowledge of their language that caused them to have confidence in him — for a time — in spite of his extraordinary attitude;

for he viewed the Chinese as barbarians and held that it would

be preposterous for a gentleman to work under them though

he might work for them; and holding that view it was his

ambition to be China's guiding spirit. Lay had a great capacity

for work, organization and administration; but his wild

obsession about his relationship to his employers doomed

him to a monstrous failure.

In 1862 he went home on leave suffering from a serious

wound sustained while fighting as a Shanghai volunteer against

a band of marauders. It is now that Robert Hart comes into

the picture. He was an Interpreter in the British Consulate

at Canton, and when in 1858 the new Customs Service was in

the making the high officials there wished him to be the local

Commissioner; but placing himself in the hands of Lay he

resigned the Consular Service and took the post of Deputy

Commissioner at that port. Four years later Lay went home

on leave, and Hart was appointed to take his place (1) — not by

Lay but by the Peking Government. It appears that Bruce,

the British envoy, nominated him; but it can be presumed

that the appointment was also due to the influence of the high

officials at Canton.

1 — The Shanghai Commissioner, Mr. Fitzroy, was appointed jointly with

him, but does not appear to have materially functioned.

At the time that Lay went home on leave the Taiping rebels

were at the zenith of their cause — it was in the succeeding year

that Gordon took command of the Ever Victorious Army —

and a scheme was mooted to form a navy manned by foreigners

to assist in fighting them. Lay being in England, it was in his

hands that the Chinese placed the matter; and the instructions

of the Government were forwarded by Hart. Whatever those

instructions were in detail, they must have left a lot to Lay's

discretion; for there were factors in the problem that were

anomalous and complicated. Obviously what was needed was

a fleet of gunboats to operate on the waterways as the Ever

Victorious Army operated on land; nominally under the orders

of, to some extent independent of — by reason of the prestige

of English officers-the Chinese high command. That nothing

else was practically possible was a fact so obvious that it is

likely it was not specifically mentioned.

Lay entered with zest into the business of ordering a fleet —

eight vessels including some monitors with heavy guns — of

equipping them and engaging officers and men. He was

properly accredited, was supplied with ample funds, the

British Government put its imprimatur on the business, and

the Queen conferred a C.B. on him.

And now we come to Lay's monstrous escapade, to his

gigantic bluff. He had engaged a naval captain, Sherard

Osborn, to command the fleet, and he drew up an agreement

with him, of which two clauses only need be quoted to show

its nature:—

' Osborn undertakes to act upon all orders of the Emperor

which may be conveyed direct to Lay; and Osborn engages not to attend to any orders conveyed through any

other channel.'

' Osborn, as Commander-in-Chief, is to have entire control

over all vessels of European construction, as well as native

vessels manned with Europeans, that may be in the employ of

the Emperor of China or — under his authority — of the native

guilds.'

Imagine that astounding act ! He had been authorized to

make whatever arrangements might in his judgment seem

desirable; and on the strength of that, appointed himself, in

effect, as Lord High Admiral of all the Chinese fighting craft

— by whomever owned or commanded — and with subordination only to the Throne. It was a case of riotous ambition —

of administrative piracy. There is the mystery of a missing

letter in this affair — a letter, following on his first instructions,

which, stating the intention to appoint a Chinese officer of high

rank to act with Osborn, clearly indicated what was expected.

Lay said that he never got that letter. If he did not, it left the

situation as already stated; if he did, it made it infinitely worse.

In due course that fleet of gunboats arrived in China; and

then the fat was in the fire. Lay boldly made his claims and,

according to the Chinese, added to them by demanding independence in revenue collection and, as a residence in Peking,

a palace of the type reserved for members of the royal family.

The Government took prompt action; it dismissed Lay

from his post but treated him financially with the greatest

generosity.

Osborn, imbued with Lay's ideas and hampered

by his contracts with his officers and men, paid off his crews

and returned to England; his conduct in the matter being

generally approved. So ended a great fiasco; but it was one

which purged the young Customs Service of a very serious evil.

In the meantime — for two years past — Hart had been in

charge of the Service, and by his tact and ability had won the

regard of every one; and now the fiasco of that fleet consolidated him in his position. There is room to wonder about

those two years as locum-tenens: what was his relationship

with Lay? How much did he know of what was being done

about that fleet? He must have been aware of Lay's character;

how, although he had laid the foundations of the Customs

Service with great ability, he had become a grave danger to it,

and had become obnoxious to all the foreign communities of

China.(1)

1 — Concerning this Sir Francis Aglen writes: — ` Sir Robert Hart placed on

record in the archives of the Inspectorate-General at Peking a complete

account of his action in connection with the Sherard-Osborn fiasco. It took

the form of a copy of a personal letter to Mr. H. N. Lay concerning all the

ground of this deplorable affair from start to finish. This letter was unfortunately destroyed with the rest of the Peking archives in 1900. My recollection of it is that it was a most masterly exposition, and, although after

so great a lapse of time I can remember no details, the impression left on

my mind was that Hart, at his end of a most delicate affair, had been throughout loyal and helpful to Lay.

I tell this early history of Hart's appointment as Inspector-General because to me it is the most interesting and pregnant

feature of his life. Lay's failure did more than give the post

to Hart; by an antithetic process it gave an object-lesson which

guided him thereafter, and it threw up in relief that tact and

wisdom in his dealing with the Chinese which made his great

success, and which, in effect, gave him for a long time by means

of leadership instead of driving the greater part of what Lay

had aimed at.

With the foundation of the Service already soundly laid by

Lay, with his own expert knowledge of revenue collection and

with the clean slate and the practically unlimited authority he

now possessed, the further building of the Revenue Department must have been comparatively simple. A great judge of

character, he chose as his Commissioners men who could take

a part in that construction and who could be quasi-diplomats

to meet the quasi-diplomatic status which circumstances forced

upon the Consuls.

And so the Service came to be a mighty thing. Here was

this great country with its three thousand miles and more of

coast and many thousands of miles of navigable rivers, with

ports open to foreign trade increasing steadily in number; and

a rapidly increasing foreign shipping. All kinds of official

action were needed of which the Chinese by themselves were

quite incapable. There were dealings with the Consuls on

revenue affairs — fines, confiscations, legal proceedings — there

was the matter of harbour control, pilots and aids to navigation

and hydrography, and later there came the subject of a postal

service. All these functions became incorporated in the

Foreign Customs, as it was called for short. Still later there

came the hypothecation of the revenue collected by the Foreign

Customs for the service of the many loans which had been

raised. Into this great business the Inspector-General — of a

later day — was perforce drawn.

The structure that he built has now an age of over sixty years.

It is difficult to see how China could have done without it, and

she cannot do without it for some years to come; but it has

reached, I think, its zenith. In due course must come the end

of its great purpose, and it will be left a memory in history,

which will be an everlasting monument to Hart.

There is another chapter to the story of his early days. It

has been said that the building up of the Revenue Department

would be to him a comparatively simple matter; there, with

his expert knowledge, he would make no mistakes; but what

about those needs of shipping on that great extent of coast?

Here he had to build for a purpose which he could not fully

understand and with unknown factors in the problem; and

because the technicalities of it lay outside his field of knowledge,

it would have the greater fascination for him. It is here we

reach that part of the Customs history which affects the story

of myself, and which so far has never been recorded.

Owing to those unknown factors in the problem of a Marine

Department, the design of the building was altered several

times, and in the end there evolved a very strange affair, a

hotchpotch thing, a patchwork, resulting from many failures;

indefinite in structure and in function, subordinate in form,

weak apparently in position. But these qualities, apparently

so detrimental, lent themselves later to a curious freedom of

scope. Indefiniteness? A little moral jujitsu could make it

elasticity. Nominal subordination? The same means could

get from it far more consideration than from equality.

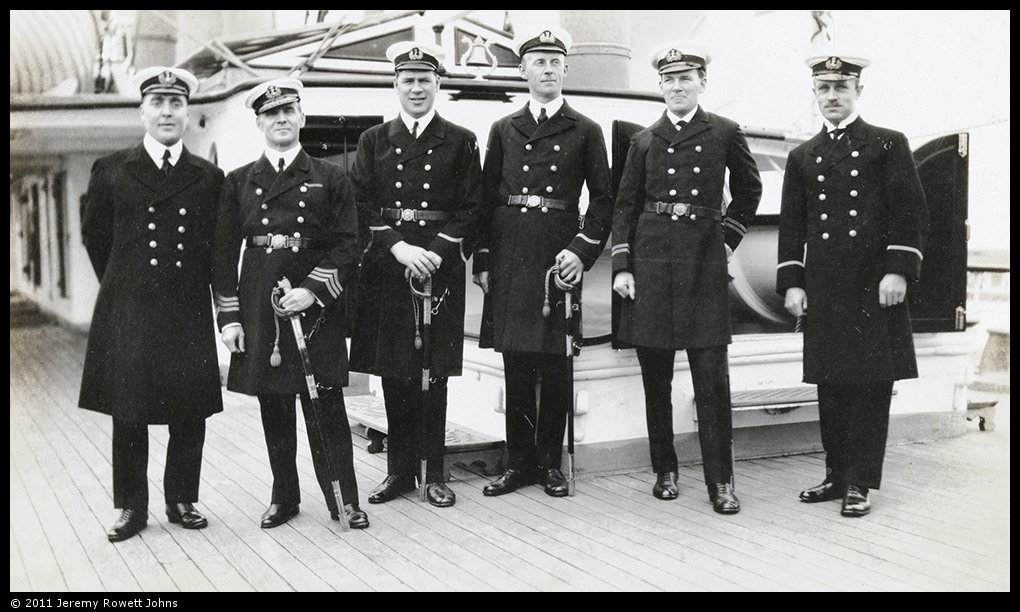

For nearly twenty years I controlled either the larger half

or the whole of the Marine Department, and looking back I see

things as I state; though I did not always do so at the time.

In the earliest days of his appointment as Inspector-General, Hart was taking passage in a coasting steamer. As he

walked the deck he would be thinking of his problems; and

mostly perhaps of the scheme of a Marine Department, for the

steamer would remind him of the needs of shipping — needs, so

far, almost entirely unmet. Lighthouses to be built, the sites

to be selected, an engineer to build them; buoys and beacons

in the approaches to the harbours; a fleet of vessels with

officers to tend these aids to navigation; a pilot service for the

several ports and Harbour Masters and Harbour Regulations;

a host of things to arrange for and get organized — things which

in other countries had grown for centuries but which here were

non-existent. Of course he must have a man — a seaman — to

undertake the technicalities, and who under guidance would

co-ordinate his branch to that of the Revenue Department.

He had already got that man — Captain Forbes, R.N. — for

Marine Commissioner, but he wanted another two to fill the

posts of Divisional Inspectors.

Now the master of that ship was A. M. Bisbee, an American,

and from that stern-faced man of great reserve, Hart, in his

quiet-mannered way, extracted all there was to know about

him. He came of a family of sailors who were born, who

were married, and who hoped to die at the New England port

where the deep-sea sailing ships that they commanded had

been built and registered. A race of sailors who considered

that to command a sailing ship was the finest thing in all

the world — a ship of those days with a vast poop and palatial

accommodation; the Captain's wife on board, her maid and

a piano; his children born on board perhaps; a floating home

in fact. Pride? There never was such a virile pride as that

of those old-time sailing skippers. Bisbee was among the last

of them. He had followed in his father's footsteps, had commanded a great sailing ship at an early age, had married young

so that he might see his sons ship-masters. Then came the

cruel realization that he must be the last of that sea-brood.

British steamers were driving the American sailing vessels off

the seas, and the future loomed with the coming decadence of

sail. So Bisbee took to steam — how and when I have forgotten.

From his tale and how he told it in that crisp way of his with

no words wasted, the Inspector-General gauged the value of

the man — his strength of character, his integrity and his intelligence; and so he made his offer that Bisbee should be

one of those Divisional Inspectors. But Bisbee said he was not

competent; he had gone to sea at fourteen years of age; a post

such as that offered required an educated man who could meet

others on terms of full equality; it required also special technics — marine surveying, for example — and some knowledge

of administration suited to the purpose of the post. And

Hart replied: ` No answer could have pleased me better; it

shows that I made no mistake in my selection. Your difficulties can easily be met. Competence? Go and get it.

I'll appoint you at once and give you two years' full-pay leave;

use that leave to go to school in any way you like.'

Hart told Bisbee about the Marine Department he had

planned, a self-contained department working side by side with

the Revenue Department and, though separate, yet co-ordinated with it. He told how Captain Forbes had been appointed

as Marine Commissioner to build up and control it; he spoke

of its need, its functions, and the fine future for the men

engaged in its great purpose.

Now of those early days, when Bisbee returned to China and

took up the Divisional Inspectorship, he told me very little,

for it was a sore that rankled in his mind and never healed, but

I gathered something. The great fiasco of Captain Forbes's

failure happened, I think, about the time of that return. He

failed egregiously; he was insubordinate to the Inspector-General — as if he had caught the Lay-Osborn megalomania. I

have no knowledge of how the I.G. felt, but it can be imagined:

keen disappointment at this failure of his plan; resentment

against the sailor who had let him down; mistrust of sailors

generally for constructive administrative purposes; a revulsion

of feeling against his offspring, of which he had hoped to be so

proud. Revulsion and resentment — it was shown later when

the rank of Bisbee and the Engineer-in-Chief was reduced from

that of Commissioner to Deputy Commissioner, owing to a

quarrel with a Revenue Commissioner for which the latter was

by far the more to blame. But there was more to it than

Forbes's failure. There was the quite recent fiasco of that

gunboat fleet. Sherard Osborn could have averted it and

turned events to his own and China's benefit; but he did not

rise to the occasion and adhered to his claim to be a kind of

naval satrap. And then came Forbes's failure; so one cannot

be surprised if Hart came to the conclusion that if you let a

sailor have his head he would bolt and smash things up.

Thus the great department was a myth; it could never now

materialize; the functions it would have had were scattered

among the Revenue Commissioners; its chiefs, in its new

attenuated form, were little more than mere advisers. And

Bisbee felt it bitterly.

In due course what was left of the Marine Department was

placed in charge of Bisbee — as Coast Inspector — and the

Engineer-in-Chief. Bisbee was permanently disgruntled, but

in a sort of sullen way was vastly keen. He had the character

and the ability to make his job — such as it was — successful;

and, by the time I joined him, the Engineer-in-Chief had built

a string of lights on those thousands of miles of coast as good

and up-to-date as any in the world. So the needs of ships

were met; and on the whole I think that what was built on the

ruins of that first idea was more efficient than the other could

have been; for in the circumstances of the treaty ports the

connection between revenue collection and control of shipping

proved to be most intimate, and two independent departments

must have fallen foul of one another. So good, once more,

came out of evil. Certainly that loose-knit organization, when

later I took charge of it, suited my purposes far better than

could have any more normal but more rigid thing.

#

[click]

[click]