3. The Coast Inspector's Work

The functions of the Marine Department grew; I obtained

sole charge of it — a new Department of Works being created

for the Engineer-in-Chief — and it approached a semblance of

what had been originally intended. The fleet of Customs

cruisers was placed under my control and the building of all

new craft; hydrographic work grew until we published our

own charts and the British Navy withdrew their surveying

vessels; harbour and river conservancy matters — except where

there were special organizations — fell into my hands; meteorological work in conjunction with Siccawei Observatory became

an affair of Far Eastern international importance in which we

took the lead. And this was in addition to the older functions

of administration of lights and other aids to navigation on the

coast; keeping track of changing channels and marking them;

issuing Notices to Mariners; pilotage, harbour control and

quarantine affairs; courts of inquiry and arbitration about

shipping accidents; and dealing with the Consuls and other

local authorities on terms of equality. Just ordinary administrative work? Quite so; but there were more technics in the

hands of one man than could be the case in any other country.

But, outside the duties pertaining to my post, circumstances

forced on me another set of activities. My previous service

with the Chinese Navy resulted in a continued connection with

it, sometimes as an informal adviser, sometimes with an official

appointment. Those were years of steadily increasing ferment

in Chinese affairs — the Boxer outbreak; the Russo-Japanese

War, fought mainly on Chinese soil and in Chinese waters;

the revolution which ousted the Manchu dynasty; Yuan Shihkai's attempt to make himself Emperor; the effect of the

Great War in which China, late in the day, became an ally; the

period — not yet for certain ended — of independent military

satraps. In all those affairs I acted as adviser to the Navy.

And there was something more.

My friend Ludwig Basse

became a trusted man to the three satraps at Tientsin, Tsinanfu

and Nanking, and so I got to know them, had the entrée to

their Yamens, and was given certain missions by them. Those

extra-Customs functions were a curious feature in my life.

Some were permitted rather than authorized by the Inspector-General; others were definitely authorized, and in most of them

I had the great advantage of my chief's advice and warnings.

My Customs work came first, — it was what I drew my pay for;

for the other work I got nothing except some decorations. Yet

what I have to say about my life in China is mostly about my

extra-Customs work. That is because it better lends itself to

telling; and so the greater part of what I have to say about my

Customs life will be concentrated in this single chapter.

The work of the Department was very interesting. It was

varied and pleasant — a few months in the office, then handing

over to my deputy and going on a trip in a large yacht-like

steamer, inspecting lights, perhaps, or starting a survey dealing

with a harbour question at a port, or something of the sort;

then Shanghai again.

My two deputies, Eldridge and Myhre, were my personal

friends, former shipmates and my own nominees. Both were

senior to me in the Service; it was just that war and opportunity

that made me be their chief; they were such splendid fellows,

so capable and so loyal. I should like to mention all the other

members of my staff, both foreigners and Chinese; of course

I must not, but I look back on them with strong feelings of

affectionate regard and gratitude.

Every year or so I made a visit to Peking and talked things

over with Sir Robert Hart, and later with his successor. I

have already told the story of that first interview with him, when

I was very crude and he resented it. That he did not score it

up against me is very plain. My other visits to him were

always a great pleasure — invariably I left gratified and pleased.

With many others whom he treated well or who have not

nursed a grievance I feel a reverence for his memory that tends

to prevent anything being said about him except in adulation.

That tendency is wrong, for to throw a decent light on the

human nature of a man of fame should be of interest.

I saw little of him, and yet I seem to know a fair amount

about him. A frequent contact is often not the closest. The

mask, which such a chieftainship as his demands, is more

likely to be lifted to the transient than to the more permanent;

besides, one hears of things, and some hear more than others;

and so, from this and that, I get an impression of his inner self.

He was a man of deep emotion that, however much controlled, demanded outlet; and one side of him was highly

spiritual. But the spiritual side in emotional natures has

often a reverse one that is very different, giving rise to those

incongruities of character that one hears of now and then.

And thus it was — in some degree — with Hart.

To me he lifted the screen but once. I had written a booklet

on Religion and the Fourth Dimension — a sort of transcendental

thesis.(1) Sir Robert Hart had seen it and now discussed it.

He had read it through without a stop, he said, and found it

intellectually very interesting; but he went on to say that from

the religious point of view it had no interest for him. The

intellectual and the spiritual were two quite different things.

1 — It seems worth noting that in that booklet, written in tool, I stated in

effect that, while we can think of the Fourth Dimension in terms of Time,

it cannot really be Time.

Then in his quiet and very simple way he spoke about his

certain faith and hope — the faith he had been brought up in,

modified but slightly by the facts of science. It was a most

illuminating thing to hear him talk in that esoteric language

of the Church, and I went away abashed.

He exercised autocratic power over a staff of several thousands for a period of very many years. In that respect his

position was unique. Such a power is apt to sap the finer

susceptibilities, and it may well be doubted if any man could

use it without grave lapses in the exercise of justice. It should

be remembered too that strength and greatness rarely march

with all the virtues. So there are some, including two or three

of high ability, who bitterly consider that their lives were spoilt

by him. But so, I think, it must always be.

I had suggested that he revert more to his original scheme

for the Marine Department and appoint me Marine Commissioner or Marine Secretary. The next day we were sitting

in his garden having tea. There was silence for a time, and

then I said: ` Sir Robert, have you ever noticed the difference

between a tree of that kind ' — I pointed to a juniper — ` and an

oak tree, which explains the difference in their size? ' His

sharp shrewd eyes met mine over the edge of his tea-cup. ` Tell

me what is in your mind.' ` Well, the juniper has a trunk and

twigs. The oak has trunk and boughs and twigs.' I paused

a bit and added, ` Won't you let me be a branch, sir? '

Could presumption have been greater ! But he took it, as I

knew he would, quite well. He smiled and said: ` So you

are returning to the charge ! I have thought that matter over.

It is now too late for me to make the change. You must tackle

my successor.'

Sir Robert's brother-in-law — the late Sir Robert Bredon — succeeded him for a time as Acting Inspector-General. He

had been deputy before with his office at Shanghai and was

very popular with the community — chairman of the race and

other clubs; a social notable. Clever and quick and with big

ideas, he seemed the very man to be a leader; yet when the

confirmation of his post was mooted, Shanghai rose up against

him — and he got a knighthood in exchange. An instructive

illustration, this, of the detriment of a certain kind of popularity.

There is not a doubt about it that reserve is a good asset to a

leader. He is human, and there must be facets of his nature

which, if known, would tend to make him cheap — ignorance

is to some extent involved in faith.

I was travelling with Bredon on a coaster, and we paced the

deck in silence. Then apropos of nothing Bredon said: ' What

do you consider are the factors making for a great success in

public life? ' I had thought of it before, so had my ,answer

ready: ` The gift of expression, for only thus can one justify

one's judgments and gain faith; absolute unselfishness, because one's cause is quite enough to think about; and a

measure of unscrupulousness exercised with great discretion

in emergencies.' — ` That is quite well put,' said Bredon, ` but

I don't agree about unselfishness. One must look first after

oneself in order to be there to do the work.' It was the

Chinese point of view so necessary for them, but so unsuitable

for us, and the answer was significant of Shanghai's attitude.

I have already told some stories about the work of the

Department when I was acting in Bisbee's place; and now I

will tell some of a later date. If there is any virtue in them, it is

in indicating how things were done in China, for stories of this

kind tend to be selected because I look back upon them with a

sense of satisfaction as exploits in a sense — though stunts is

nearer to my meaning: something that is lighter hearted and

less ambitious. I regret this fact. I should so much rather

have been a man of no affairs, who could tell the tales of what

he saw and heard; or — a more ambitious wish — a man of

great affairs who could sink himself in the story of the important

and interesting events with which he had to deal. But I was

neither. I was a man of comparatively small affairs, and

because of that my memory and vision tend to be dominated by

my little problems of the past. Yet it may be that these

personal accounts will throw some special light on conditions

as they were in China.

The subject of improving the waterway to Shanghai had

long been agitated. Mr. Hewett, the P. & O. Agent, a man

prolific of ideas, drew up a scheme in about '98 and tried to get

me to support it. But it was teeming with defects; it took

away from China the sovereignty of the river; it required

China to pay half the cost, and the only representation given

to her on a board of nine was the Customs Commissioner — a

foreigner. Hewett was stubborn; it was his pet creation and

he would not modify it. The Chamber of Commerce, attaching no importance to the details, which they believed would

be amended later if the application came to anything, gave it

their approval and sent it to the Legations at Peking. The

Legations also put their imprimatur on this hopelessly impracticable scheme; then filed it in a pigeon-hole.

In 1901 there carne the framing of the Boxer peace protocol,

and some one took that scheme of Hewett's from its hole and

made it Annex No. 17. I find this entry in my diary: ` 11th

September 1901. Called on some of the Chamber of Commerce Committee about the Conservancy Annex. They all

express regret for having put forward such a rotten scheme.'

It was A. E. Hippisley — one of the Customs Commissioners

assisting the Chinese plenipotentiaries in the framing of the

new commercial treaty — who made a suggestion for a change,

and, as a result, China agreed to pay the whole cost based on

the other scheme's estimate, the work being conducted under

the direction of the Chinese Taotai and the Customs Commissioner; but this scheme — the best that could at the time

be arranged — also had grave defects. There could be no

certainty of what the work would cost, and a fixed sum had, in

effect, been provided, and nothing for later maintenance.

The Engineer appointed was de Rijke, a distinguished Dutch

expert and a personal friend of mine. He had enough to do

with the difficult technicalities of his task; finance and looking

to the future was not his job. The Taotai, of course, was a

figurehead; and the third was Hobson, the Shanghai Commissioner, and what he thought about the future I never knew.

After four years' strenuous work the notorious Woosung Inner

Bar no more existed. The work was a notable and creditable

performance; but of course other operations were now needed,

to say nothing of maintenance; and the funds were nearly

spent ... A further eight million dollars were asked for from the

Government — something like twice as much as the original

grant. The Chinese Government was quite naturally very

angry at this unexpected situation and refused to renew the

contract of de Rijke, which expired about this time.(1)

1 — Mr. H. von Heidenstam, a Swede, was then appointed by the Nanking

Viceroy. The choice — as it happened — was very good.

A farewell dinner was given to de Rijke, and a group of leading

Consuls-General and of leading business men attended. There

were speeches at that dinner which I did not hear; but de

Rijke spoke of the perils impending over the situation and

advised that faith be placed in me.

And now I have a story about a sudden opportunity and the

grasping of it. I had attended that dinner merely as a social

function. Shanghai conservancy affairs should have been,

but had not been, my business; I had always had — as an

onlooker — an anxiety about it, but I had never even turned over

in my mind a constructive scheme. But after dinner when we

were standing about in groups and I had been silent, some one

said: ` WeII, Tyler, haven't you any ideas about it? ' And

an inner prompting came to me. ' Yes, I have ideas; would

you really like to hear them? ' and the group increased

around me.

' For years Shanghai has talked a lot about conservancy and

complained and criticized, but never yet has it put forward a

practicable scheme. Do it now. A more suitable management is needed for one thing — that can easily be arranged; but

the dominant matter is the provision of money. The Chinese

will not give it; it is not desirable that they should; the

obvious thing to do is to find the funds yourselves. Why not?

A tax on trade that would meet all needs would not be felt; it

would be incident not on Shanghai but on the millions that

Shanghai trade supplies.' This expression of opinion and its

practical acceptance took about five minutes. It was arranged

that on the morrow I should discuss the matter further

with Warren, the British Consul-General, and Landale of

Jardines.

I got up early in the morning and drafted out my scheme.

The same board as before with the addition of either myself

or the Customs Engineer-in-Chief; but now there would be

a consultative committee of commercial interests. At eleven

I started for the British Consulate; but on the way I got a

brain wave. The crux of the matter lay with the German

Consul-General. He had not been present at that dinner; he

had always been in opposition to the Board; he had got out a

German river expert to criticize de Rijke in the hope of getting

the work in German hands. Unanimity among the Legations

in Peking was necessary for success; the Germans, if they

liked, could block it; so I changed my course, crossed the

Soochow Bridge and called on Dr. Knappe, the German

Consul-General.

I told him exactly what had happened, including the brain

wave that made me visit him before seeing Warren; that if I

could not get him on my side I would give the matter up, for

otherwise it would be useless. He read my draft, and then

with some impatience said: ` Can you not see the difficulty I

have in agreeing to this? The Commissioner may be of any

nationality, but you and the Engineer-in-Chief are British and

you are never changed; and, of course, you will use your

position to further your nationals' interests. I cannot blame

you for it; it is natural; but it is very disadvantageous for

us.' To this I replied with genuine deep feeling: ' Dr. Knappe,

really and truly you are wrong. So far as I'm concerned my

only fear would be that, to avoid a suspicion that I might be

favouring my co-nationals, I might act unjustly to them.'

Then Knappe got up from his chair and moved about the

room with his fingers in his hair and used quite unintentionally

a curiously biblical expression: ` Almost you persuade me !

But it is incredible ! It is impossible ! '

In my other dealings with Knappe I had always found him

eminently reasonable, and now he calmed down and agreed

that some such scheme as mine was the only practicable one.

He would tell the German Chamber, and I could go ahead at

once. At the time I took the credit of persuading him to

myself; but later I had some reason to believe that a German

— I think a member of his staff — had made about the same

proposal.

Within a week the scheme was sent to the Legations with

the unanimous approval of all those locally concerned. It was

some years before it was put into operation. It is in force

to-day, and believing, as I do, that in due course Shanghai will

handle a larger trade than that of any other port in all the

world and will require the greatest river engineering works

to do it, I can look back with some complacence on the part

I took in its creation.(1)

1 — This organization was preceded, as has been stated, by Hippisley's

scheme. The genesis of that one was also curious, and, if not recorded here,

is likely to be lost for ever.

Hippisley was a Treaty Commissioner and as such was in touch with

Liu Kung-yi, the Nanking Viceroy. Old Liu was sick and very feeble —

he died soon after; but his mind was sharp as needles, and he was furious

at the imposition of that annex, and not only on account of its perniciousness,

but because, on a matter within his jurisdiction, he had not been consulted.

So he begged Hippisley to do all he could to get the monstrosity removed

and replaced by something else. Hippisley did his best, pulled all the

strings he knew, and failed — the protocol was the price that China had to

pay for peace. But later there came an incident that turned defeat to

victory. It was found that, under the complicated taxation clauses of

Hewett's scheme, certain properties would be taxed twice over, and to

remedy this injustice the foreign ministers decided that those clauses should

be interpreted in such and such a manner. Then Hippisley with fine

perception saw the opportunity. He notified the Viceroy that, as an instrument of the peace protocol, the annex could not be amended; it could

only be amended by ordinary negotiation on equal terms. That argument

was irresistible, and so Hewett's scheme was scrapped.

In 1902 — as an offshoot of the Boxer peace protocol — came

the revision of the commercial treaties with Great Britain

under the leadership of Sir James Mackay, now Lord Inchcape;

there was a mass of stuff about Customs duties and other matters;

and there was a searching for odds and ends of claims to be

inserted — such an opportunity might never come again. I was

in close touch with A. E. Hippisley at this time — a man of

wisdom and great breadth of vision; and by him I was kept

informed of what was going on. In the draft convention I

read that China undertook to remove the rocks that obstructed

the approaches to Canton, as well as the artificial barriers which

had been placed during the French and Japanese hostilities.

Hippisley had done his best to get these impracticable clauses

taken out, but without success. I was personally concerned

because the onus of the work would most likely fall on me, so

I approached Sir James directly, and in the end I struck a

bargain with him. I would tell him of a port to open if he

would delete the clause about the Canton rocks; and that was

how Wanhsien was opened. So the clause about the rocks

was taken out, but about the barriers — massive structures of

blocks of stone and steel screw piles — Sir James stood firm.

Two years later I got brief instructions to consider what had

best be done to meet the treaty stipulation. To remove the

barriers would cost many million taels; it would upset the

regimen of the channels, and instead of helping navigation would

seriously embarrass it. The interest in the matter was chiefly

that of Hongkong shipping, so I called upon the Governor, Sir

Mathew Nathan, and explained the situation about that silly

clause. I suggested that I should widen the entrances through

the two barriers, and with that done the question of the treaty

clause should without formality be allowed to drop. In this

and other matters I found the Governor most approachable

and reasonable; he had a clear vision of the matter and

agreed.

For that work I needed divers, and I had not any; so

I called on Admiral Noel at his office at the Naval Yard.

He was in plain clothes, and he looked much more like a

country squire than an admiral. Across the desk I told the

story of my job and how I needed divers. He spoke, but not

to me; he spoke to himself and quite loudly: ` Ah! — an

Englishman — and he comes to me for help — important operation — for a foreign Government too — and an Englishman to do

it — a sailor too — h'm, h'm — yes, he deserves assistance.' And

then he let out a yell, which could have been heard half-way

across the harbour; it was for the signalman who was just

outside the door. ` General Signal: Volunteer divers required

for service under the Chinese Government.' The Admiral now looked me in the face with a smile of wide benevolence

and held out his hand to end the interview; and all the time

he never said a word to me.

While that work on the barriers was being done — it took a

year or so — I interested myself in the bunding of the Canton

frontage. Something had already been begun in haphazard

fashion, but now I got it systematized and laid down lines of

clean curved bund 'walls of several miles in length. There was a

curious feature in this undertaking which, much more than the

work itself, deserves recording.

In about 1370 the conquering

Ming dynasty ordered that the soldiers of the previous Mongol

garrisons — the descendants of the famous hordes of Ghengis

Khan — and their families should be slaughtered. At Canton

there had been intermarriage and absorption in a century of

Mongol rule, and enmity was dead, so there was reluctance to

fulfil this drastic order; consequently it was reported to the

capital that they had been driven into the river, and by inference

drowned. They were not drowned; they were allowed to

live in boats and in piled shacks below high-water line. And

so they had lived and bred and grown for five hundred years

and more, and it was no one's business to institute a change.

These were the Tankas; fine-looking men and pretty girls,

from the latter of whom the famous flower boats drew their

staff. Now, when I dealt with that matter of the bund, I found

great areas of foreshore, the value of which reclaimed was

needed for the project; but these areas were studded thick

with Tanka squatters. So I approached the high officials and

pointed out that the time had come to remove the ban from

these hard-treated and deserving people; and it was done.

There was money in the business, so that was why.

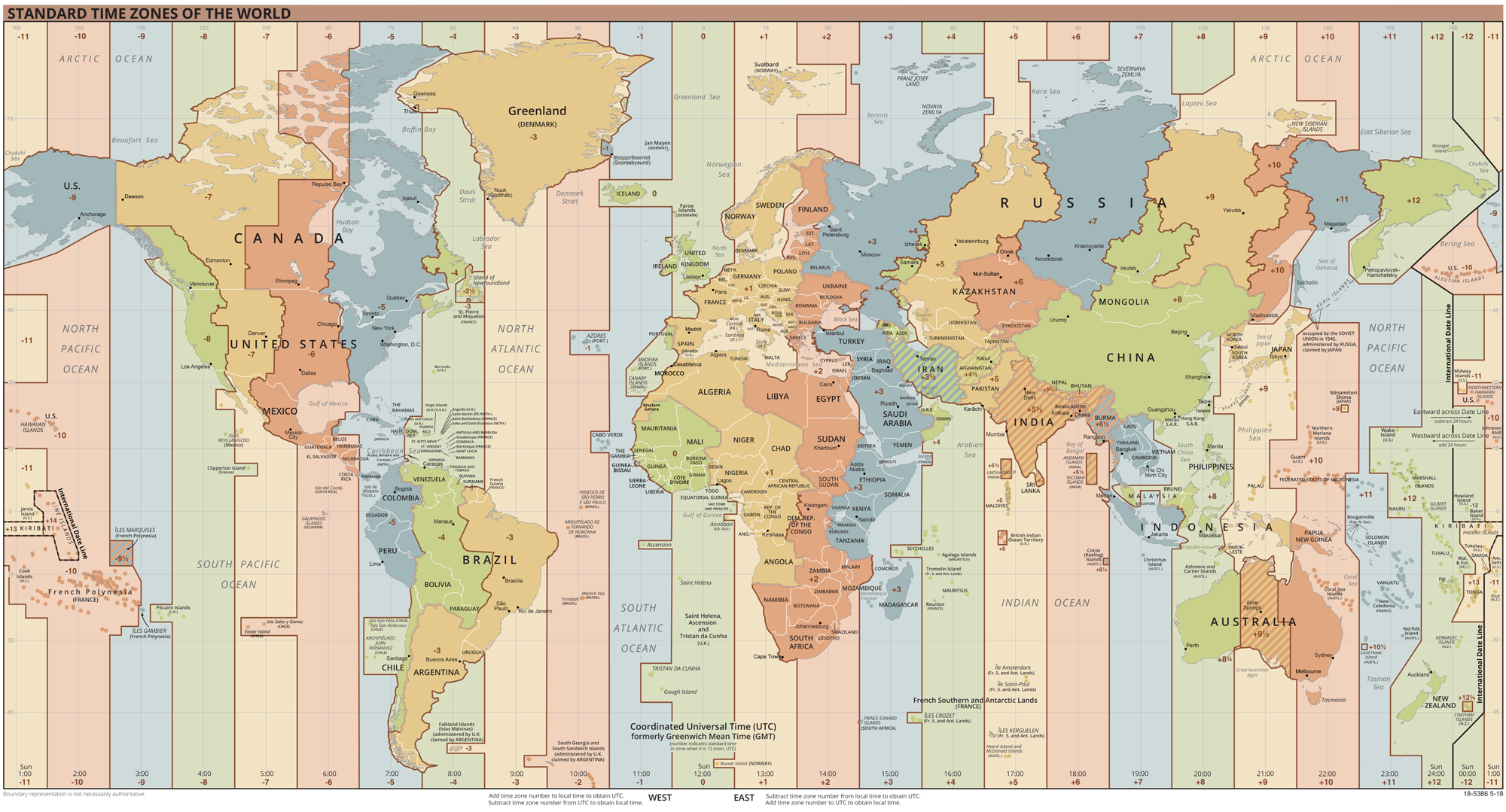

It is only the older generation who remember when in

England there was railway time — which was Greenwich time

— and local time, which differed in each town and village.

Now in China we had local time, and it was Father Froc, the

eminent Director of Siccawei Observatory, who made the

suggestion that I attempt to get standard time adopted — a

seven hours' difference from Greenwich for the coast, and six,

five and four hours' differences for the interior.

It seems some undertaking, does it not? It would really

be so in any other country and would require at least an act of

Parliament. But in China, in those days, — well, let us see

how it was done.

I wrote to the Inspector-General on the subject and explained how, if he approved and later would give the necessary

instructions to the Service, I could arrange the whole affair

informally, quietly and without publicity.

The Inspectorate approved. Over a cocktail at the Shanghai

Club I discussed the matter with the foreign adviser of the

Chinese telegraphs. Quite a sound idea, he thought; he

would do his part and a week's notice would suffice. Then a

visit to Tientsin to see the manager of the Peking railway —

the only railway in the country at the time; and he concurred.

Now came the question of Hongkong, with Canton sixty miles

away; and there lay the only snag.

If coast time was established, Hongkong would sooner

or later have to fall in line; but unless she did so willingly

and concurrently there would he a lot of fuss and the undesired

publicity, and the Peking Government would be incensed at

the Customs undertaking such a matter. So I called on the

Honourable the Harbour Master, a member of the Legislative

Council, and on the Astronomer Royal — it is a fact that little

Hongkong has one — as these would be the two that the

Governor would look upon as experts on the subject; but I

failed entirely to bring them to my side. The sailor-man an Irishman and as stubborn as they make them — knew me

well enough to say that he would see me go to hell before he

would agree that a British colony should take a lead from China.

The Astronomer — an old, old man — said that the change

would affect the sequence, and thus the value of his twenty

years' collection of observations of temperature and humidity.

He was sorry but he could not possibly concur. It was an

example in miniature of how big affairs are often dealt with.

I was disappointed but not downhearted. These two

were the expert factors; the factor of common sense lay with

the Chamber of Commerce, and would be reflected by the

unofficial members of the Council. The problem was now

to get them prompted with the facts.

My friend Hewett, the P. & O. agent, who had originated

that detrimental scheme for the conservancy of the Whangpu

river, was now stationed at Hongkong. I knew well the active

nature of his mind, his imperviousness to reason, his love of

leading in some new idea and his fondness for a speech. So

I had him to dinner at the Club. I told him of my aim, of the

facts about it, of the Astronomer and the Harbour Master;

and I showed some measure of despondency. I did not ask

for his assistance, nor mention the Chamber of Commerce or

the unofficial members of the Council; but I filled him up

with the technics of the matter — about zones of longitude and

the rather complicated benefits that would result to typhoon

warnings. I spoke of the history of the movement in the

world; what America had done; the fact that distant Kashgar

would be affected and that other states would follow suit. And

so I left my seed in the fertile soil of Hewett's brain; and it was

the last I ever saw of my active-minded friend.

I was working on the Canton barrier business at this time,

and when I next paid a visit to Hongkong a friend said at the

Club: ` That scheme of yours came up last week before the

Chamber. Hewett made a perfectly marvellous speech about

it. Where he manages to get his detailed facts, God only

knows.'

So things had gone exactly as I planned — a rather snivvy

business, but quite successful.

A few weeks later an I.G. Circular was issued ordering that

on a certain date the clocks at customs houses should be

altered in such and such a way. So as regards the coast the

thing was done, and, as far as I remember, no reference to the

fact was made in any paper. Subsequently the other zones

were instituted; and daily from Shanghai was tapped out

standard time to every telegraph station in the Empire.

Whether Japan was ahead of us in this I have forgotten; but

the Malay Settlements and India followed suit. The Siamese

Government, which I approached informally, declined to join

the movement. To round off my ambition in this matter

Siberia and Russia should have copied us; but they did not,

either then or later.

Is that the end of progress in the matter? No. There

must be one step more, but only one. You know that a cable

sent from England will reach America at a date some hours

before the sending of it. Well, it will not be in our time that

we can fly the Atlantic at such a speed as to arrive before we

left — as shown by standard time. But unquestionably this

generation will make that journey at such a speed that time, as

measured by the sun, will be nearly stationary; and in a flight

to China, a day — as measured by the sun — will be but little more

than half a normal day. Thus for travellers' time-tables our

present standard time will be a useless thing. It will be

discarded for that purpose, and Universal or Greenwich Time

will be used instead; and later Universal Time will be in

general use for all purposes except those which depend on

light and darkness, such as hours of work and feeding and

amusements. To meet those purposes the clocks will have a

second hour hand, painted red perhaps, to indicate a Routine

Time. With that extra hand each country, county, town or

even village will be able to play about to its heart's content

in saving daylight, and then will cease that cruel prostitution

of real time, which now takes place.

#

#