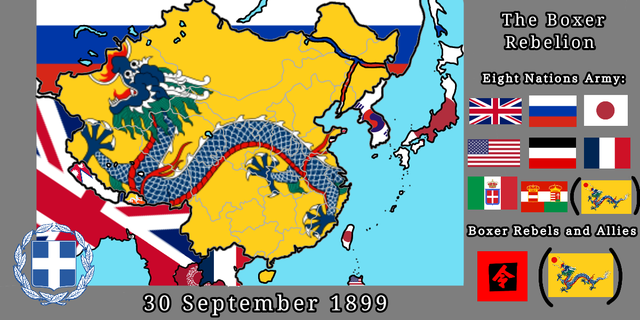

1 — Known as the Yü Man-tze rebellion.

This exchange of letters with the Chinese Commander-in-Chief may

be of interest: —

25th June, 1900.

— DEAR ADMIRAL YEH,

You know the friendship I have

for you and your officers — that I identify myself with you; and you may

imagine how anxious I am that in this serious crisis the Chinese fleet should

act on lines that will conduce to its honour as well as to the best interests

of your country. The seriousness of the situation lies in the fact that the

initial successes of a bloodthirsty and ferocious fanaticism will lead not

only the common people but also many officials to believe that the Boxer

programme will be carried out, and the foreigners driven into the sea. It

is only men who know the power of Western nations — like yourself — who

will realize the utter futility of the attempt; the whole world is against it.

The Boxers and the officials, officers and soldiers who join them, are greater

enemies to their own country than they are to the foreigner. True patriotism lies in putting down this madness and substituting sanity.

I see clearly

that your proper course is not merely to look on and be passive, but to take

such action as may be possible to combat the spread of the Boxer movement.

You must, however, expect that at Shanghai the collection of your fleet will

be looked upon with some suspicion. The Consuls, I am sure, know how

you and your Captains are on the side of law and order, but the community

generally is liable to be apprehensive; and, when you remember that your

Government itself has grossly violated the sacred rights of diplomats, it is

not much to be surprised at . . . —

(etc.)

H.I.M.S. Hai Yung,

Off Taku Bar, 4th July,1900.

— My DEAR MR.

TYLER,

Many thanks for your kind and considerate letter.

My duty with

this fleet is to maintain friendly relations with all foreign powers and to be

on the side of law and order. The Captains under my command know

well how to carry out my instructions. The ships which entered Shanghai

harbour were for coaling only. They are now distributed along the

Yangtsze valley to protect the lives and property of foreigners. The Haichi

was at Miautau last week and had all the Tengchow missionaries on board

for safety. She towed the American battleship Oregon, which had struck

on a pinnacle rock between Howki and Miautau Island, out of danger. The

Hai Yung is detained here by the Admirals of the foreign powers, so the

situation of myself is most unfortunate. The insane action of our Government is one of a most peculiar character. I hope the final settlement will soon arrive, but the terms will be a very difficult question . . . —

(etc.)

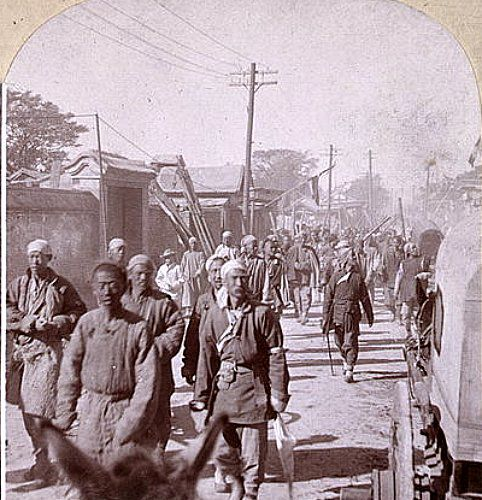

frenzied gesturing to render them invulnerable, gave themselves

the name of Ihochuan or Boxers. And Yii-hsien actively and

openly encouraged them in their hostility to missionaries and

other foreigners and in their slaughter and pillaging of converts.

frenzied gesturing to render them invulnerable, gave themselves

the name of Ihochuan or Boxers. And Yii-hsien actively and

openly encouraged them in their hostility to missionaries and

other foreigners and in their slaughter and pillaging of converts.