chapter 11

Reflections on hard times

After the misery of the camp I was so happy to be free. The happiness and our repatriation to Tsingtao allowed me and my friends to catch up on life.

The US friends I had were generally young and well behaved. They were under strict discipline to behave themselves or face the pain of being returned to the US in disgrace. With them as friends I thoroughly enjoyed myself. I went to dances, movies, restaurants, dressed in modern clothing and was able to pick my companions. In addition, I had a good job with good pay and had above all: privacy and a lot of freedom.

Having money in one's pocket enabled me to go places. It allowed me to go to Singapore from Australia and also to Japan. On reflection, losing the ability to make these choices as we all did when we were prisoners of the Japanese is one of the privileges most preciously lost.

I know that a lot of people lost a lot of privileges during the war. Some more than others. Many lost their lives. Soldiers and civilians alike died and my sympathy goes to those who survive them. My family and I have a lot to be thankful for. For example, we were not brutally mistreated as were many other prisoners of the Japanese.

We were thankful we survived. I believe we should never, as civilians, have been imprisoned in a way which prejudiced our well-being. Like many others, I often ask: what did we ever do to deserve that? Especially what was done to my brother and me ― both young children at the time who surely were completely blameless when it came to war.

I know we were lucky to have survived and I appreciate that. Although I lost a lot in the camp, I believe now that I really gained a lot. I learned that people must help each other and try to be happy with whatever happens and make the best of things ― however difficult that may be.

My father came through the turmoil very well. He just got on with living and through hard work made a good life for himself and his wife in Australia. My parents have long since passed on. My brother and I are both happily married with children and grandchildren. We see daily the results of stresses and strains on people in today's society and witness how many of them succumb to their misfortunes despite access to government assistance and counselling. We did not receive any counselling or government assistance of any kind. Nor did we receive any pensions or subsidies. The only compensation my brother and I received from the Chinese authorities for our family house left by our parents was less than $A4000 ($US2600). The payment, which we received almost 50 years after leaving Tsingtao, was based on 1945 valuation levels.

For some time I have been a member of the Association of British Civilian Internees: Far East Region, (ABCI FER) which has been fighting the Japanese Government for many years for compensation for its members but so far without success.

Civilian victims such as me and my brother are a long way down the list of possible recipients of compensation. Sadly, the unfortunate comfort women from Korea and other places who were forced into years of prostitution to Japanese servicemen before and during World War II have not been compensated.

Even the citizens of Nanking (now called Nanjing) have not had a proper acknowledgment, let alone apology or compensation from their former enemies for the destruction of their city, the systematic murders by the Japanese Army of the city's residents and the many humiliations visited on the city's survivors.

Our chances of getting some form of compensation from the Japanese ― let alone, an apology ― are slim. Be that as it may, I have been prepared for a long time now to put the past behind me and try to forgive, if not forget.

For many years in Sydney I have involved myself in voluntary community service work. In 1997, I received an award from the Ryde City Council for being the most outstanding individual volunteer of that year.

For the past nine years I have also been a helper at one of Sydney's leading museums of applied arts and sciences — the world-famous Powerhouse Museum.

Part of my job at the Powerhouse is to greet Japanese tourists and introduce them to the museum. I have always made them welcome and strived to make their visit enjoyable. I have never mentioned to any visitor to the museum my experiences under the Japanese during World War II. I have pushed that to the back of my mind as much as possible.

But an incident occurred recently which made me wonder whether the Japanese people of today are aware of the events of World War II and the responsibility of their governments in relation to many of the atrocities that occurred at the hands of their military forces. This incident occurred on Easter Saturday 1999 [April 3] at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, the Australian national capital. I was visiting the memorial's exhibit to civilian internees. With Bob and a fellow Wei-Hsien internee, we saw a group of Japanese tourists led by a young Japanese woman guide walk past the memorial to the almost 2000 Australian prisoners of war who were murdered at Sandakan after the war ended.

One of the Japanese tourists went to enter the Sandakan exhibit room followed by several others but they were promptly called away by the guide who directed them to the nearby atomic bomb exhibit. The Japanese guide started to point out to the group the burns inflicted upon Japanese civilians by the atomic bombs. My friend, the ex-internee could not help himself. He said to the tour guide: "Why didn't you take them in there?" indicating the prisoners of war memorial.

I was shocked to see the instant reaction of the young Japanese women tour guide. For the first time since my imprisonment, I saw a Japanese in a rage. She was speechless with fury for a few seconds. She then spat out while shaking her finger at him: "That is my business, not yours." She spoke so loudly that all the other memorial visitors nearby stopped and stared. Her verbally violent reaction took me back to China during the war. The Japanese tourist guide's response left me wondering whether Japanese today are only fed information which tends to minimise or conceal the disgraceful role Japan played in that terrible war.

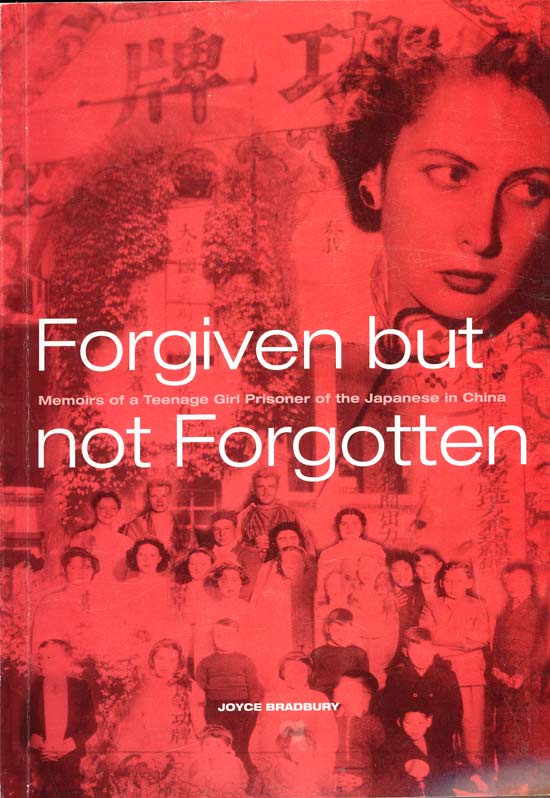

I have already written that I have forgiven but something within me will still not let me forget.

#