chapter 14

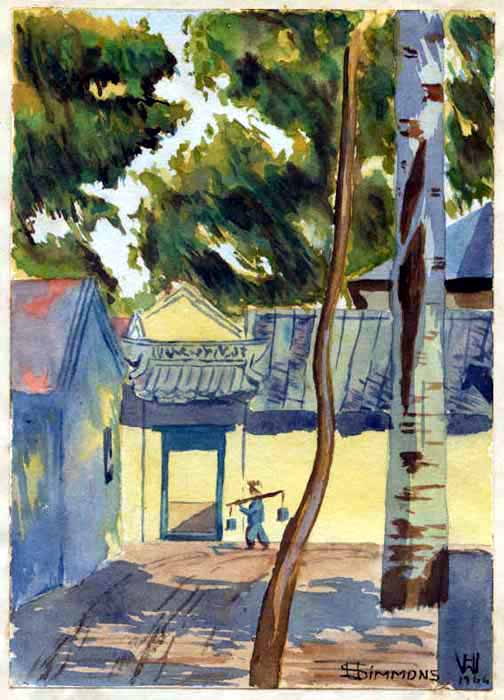

Another view of Wei-Hsien

In the writing of this book, I have attempted to check and double-check my recollections against those of others as well as refer to relevant documents. Because I was a child in Wei-Hsien, I was not privy to many of the details known to the camp's leadership.

For instance, I was not aware when I was interned that early in the Allied-Japanese conflict, some civilian internees were offered repatriation to their home-land or a neutral country. The former US Ambassador to China and ex-Wei-Hsien internee, Arthur Hummel, confirmed to me in March 2000 that a group within the Peking internees of which he was a member were offered and took repatriation before the remainder of the Peking internees were brought to Wei-Hsien. The terms of the repatriation involved the switching of Japanese internees in the US with Japanese-held internees. The internee transfers were carried out using a neutral intermediary. Most of the Japanese-held internees who were repatriated from Peking were US citizens. After that repatriation, many of the Peking internees including Mr Hummel were brought to Wei-Hsien, well after the Tsingtao internees first arrived.

In the worldwide web electronic archives of the Billy Graham Centre (http://www.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/archhp1.html ), ex-missionary Martha Henrietta Phillips, in an oral history transcript extract of her life, says that some Chefoo internees took advantage of a repatriation offer but it was only a handful because many of the people interned at Chefoo (prior to Wei-Hsien) were of British citizenship. She adds that the British group of countries would not meet the Japanese terms for repatriation which she says were five repatriated Japanese for one repatriated British citizen.

In 1943, there was a further repatriation offer made and "a considerable lot", to quote Mr Hummel, left the Wei-Hsien camp. Their departure was in the third quarter of the year.

Among this tranche of departing repatriated internees was Dr Augusta Wagner, a professor of economics at Peking's Yenching University.

Shortly after arriving in the US in early December 1943, Dr Wagner was asked to write a report on conditions at Wei-Hsien and compare them to conditions at an American-run internment camp at Crystal City, Texas.

Her report to the US State Department has been released under the terms of US freedom of information legislation. The handling of the report within the department proves that in late 1943 senior US Government officials knew of the conditions under which we were being held at the time of Dr Wagner's departure.

In her report, Dr Wagner makes the point that the American-held enemy internees were well treated in Texas and that comparison of their conditions with those at Wei-Hsien were as different as chalk and cheese.

Some parts of her recollections of Wei-Hsien differ significantly from mine. The differences, I suggest, are largely due to the camp's Japanese regime becoming stricter and meaner to the inmates from late 1943 until our liberation.

Because of the significance of Dr Wagner's comments about how she saw Wei-Hsien, I have included them in this book. Her comments have not been published in a book about the camp. Where necessary, I have paraphrased Dr Wagner's report.

Dr Wagner wrote of Wei-Hsien: "Situated between Tsinan and Tsingtao in the interior of Shantung, about 150 miles south-east of Tsinan. The camp is located on the premises of the former Presbyterian Mission compound. The compound is situated about two miles from the town, Wei-Hsien. The compound was attractively landscaped with shrubbery and fine old shade trees, some 60 years old. The climate is pleasant in the spring and fall [autumn].

"The summer heat begins in May, reaching its climax in the month of August. The rainy season begins in August. Heavy rains lead to roads being flooded, walls collapsing and flood waters reaching the window sill level of many houses. Rooves leaked. Rain poured into dormitory rooms, kitchens and mess halls. Winters cold and fairly dry. Bitter cold in December, January and February, moderating somewhat in March, but still cold.

"Wei-Hsien is probably as hot as [the Texas Crystal City] desert camp in the summer, but the heat is humid. The trees at Wei-Hsien provide some relief and shade from the heat indoors, which is not true of the [Crystal City] camp visited. The winters in Wei-Hsien are undoubtedly much, much colder than the winters at the [Crystal City] camp."

Dr Wagner says when she left the Wei-Hsien camp there were 1800 internees.

"Internees were housed in basement and upper storey classrooms of school buildings, in a wing of the hospital and in Chinese former student dormitory quarters [made up of] long rows of single rooms with separate entrances to each room. Classrooms were used as dormitories to house unattached men and women, certain buildings at one end of the grounds for women, [the] other end for men. Number of persons in dormitory classrooms ranged from 10 to 30 [with] no curtaining, no partitions provided. Each person supposed to have 45 square feet [4.2 square metres] of space.

"Dormitory rows of single rooms assigned to families. Rooms 9 feet by 12 feet [about 1.5 metres by 2 metres] containing two to four persons, depending on size of family." [Accommodating] Four persons barely possible in summer. If there is to be a stove in room in winter, [it is] impossible for four [people].

"Armies had previously occupied buildings. Buildings in disrepair, wind and dust swept through cracks and crevices. Difficult to keep warm in winter. The walls were white-washed and floors painted in preparation for internees. Many of the rooms infested with bed bugs and fleas. No beds, cots, tables, chairs provided. Internees were permitted to bring bed and bedding. Internees who were transferred from Chefoo to Wei-Hsien just before we left [for repatriation] were not permitted to bring their beds, [they] were sleeping on floor. No running water or toilet facilities. Space available per person 34 to 54 square feet [3.2 to 5 square metres.] Official allowance is 45 square feet.

"Stoves [March 1943] in only a few quarters — [for the] aged, small children, sick. Small stove in large dormitory rooms totally inadequate. No kindling wood or paper provided. Coal had to be picked by hand from coal heap, considerable distance away. No containers for carrying provided."

For washing, toilet and laundry facilities, Dr Wagner reports that the Wei-Hsien facilities contained: "Four blocks of 5 and 6 toilets each, Japanese squat type. Originally meant to flush, but never had tanks connected. Inconveniently located. So close to some buildings that the dormitories were never free of the toilet and cesspool stench, so far away from other buildings as to require a long walk in the outdoors to reach them. 23 toilets in all for 1800 people [resulting in] morning and evening long queues. In reality, [toilet availability] average was more nearly one to 100 people as some of the toilets were continually out of order. The water supply was so limited that very little fresh water was allowed for flushing toilets. Internees brought their own slop water and deposited it in two earthen-ware jars at the entrance to toilet block. Used empty tin cans to flush toilets.

"Drain pipes leading to cesspools small and frequently clogged. [Because] cesspools had inadequate depth and diameter [they] usually overflowed, flooding surrounding areas with filth and stench. Chinese coolies finally allowed to come in regularly to empty Chinese latrines and to carry away some of the contents of the cesspools.

"All requests to be allowed to dig deep army-style open latrines turned down repeatedly. In August [1943] buildings containing flush toilets finally screened. No screens [on] Chinese-style toilets. Swarms of flies in toilets and around cesspools.

"No toilet paper supplied by authorities, except for a few months to hospital [and inmates had] great difficulty in getting disinfectant and cleaning materials."

Dr Wagner reports there were "four washrooms in toilet buildings. A number of faucets arranged over cement troughs. Only a trickle of water occasionally available. 90 per cent of internees used hand-basins in own quarters ― carrying water from one of several wells."

Shower facilities consisted of "one shower room for men, one for women with about 14 to 16 shower heads in each. Average one shower for every 60 persons.

"Showers [were the] only place [where] running hot water available. Because of limited amount of water, women only permitted three showers a week, men daily showers. Long queues [for showers] and there was no running water in any living quarters.

Laundry facilities consisted of "five stationary tubs in hospital basement and two in another building. Internees did their laundry in hand-basins and galvanised tin pails (if they could borrow one). Later, [it became] possible to send sheets, towels, pillow-cases, heavy clothes to laundry outside. Expensive and badly done. Not many could afford this."

On medical facilities at the camp, Dr Wagner notes the "hospital at Wei-Hsien was originally a fine little hospital. When internees arrived, only the outer shell left. Everything moveable had been taken away. Great big gaps in wall where pipes had been torn away. Place littered with many months accumulated filth and debris.

"No cleaning materials or equipment provided by authorities. Nurses, doctors, internees went to clean up place, [they] were able to find enough beds for three 12-bed wards, five beds for children, an obstetrical room. Patients brought their own mattresses, bedding, linen, wash basins, etcetera.

"Internees accumulated enough equipment for four outpatient clinics [which were] rather sketchily furnished.

[Internee] "doctors gave Japanese authorities list of drugs needed, nothing resulted except a few minor drugs. Copy of list was smuggled out to Swiss representatives who in July [1943] got the drugs, along with some cereal and tinned milk to the hospital. Each person in camp was assessed by internees' committee $60 [Chinese] to pay for his share of cost.

"Japanese eventually furnished a rather cheap operating table, a gasoline burner without gasoline, surgical equipment enough to open a boil, some mattress ticking, some sheets, some gauze.

"Hospital facilities and equipment dangerously inadequate together with lack of drugs when those on hand used up [because] Wei-Hsien is in isolated community of no hospitals. Permission was given for patients to be taken to Peking ― a long, dirty, difficult, expensive journey.

"Medical situation serious ― save for good doctors and nurses among internees. None supplied by Japanese.

On Wei-Hsien's cooking facilities, Dr Wagner says: "There were three mess halls with attached kitchens and a small hospital diet mess hall [for patients]. The Peking mess [indicating where the internees were first assembled before Wei-Hsien] served 400 to 440 people, Tientsin mess 600, Tsingtao mess 800.

"A small storeroom and butchery was assigned to each kitchen. In the case of the Peking kitchen [it was] a distance away. A family-size electric refrigerator and an ice-box were eventually installed in the butchery."

Dr Wagner writes: "A result of the lack of refrigeration [meant] much food had to be discarded because of spoilage. The camp suffered from epidemics of diarrhoea and [what] appeared to be dysentery.

"There were no equipped, stocked, refrigerated warehouses. A former residence was used as a central storage house. Vegetables, meat and fish rotted and spoiled because of poor storage.

"At the end of [the 1943] summer, permission was granted [by the Japanese] to internees to build an ice-box for general storeroom for meat" which was "poor, makeshift. [The] Japanese storekeeper [was] inadequate for job. Finally persuaded [Japanese] ... to allow internees' supply committee to divide food among mess halls.

"Meat came from army slaughterhouse 30 miles away. [It was] sent by train, unrefrigerated, often uncovered. Rooms for preparation of meat swarmed with flies, meat covered with larvae in brief period of time necessary for preparation. "Kitchens painfully small. Kitchen where food for Peking internees was prepared was no larger than a kitchen in a modern American small apartment. But there was nothing modern about the kitchen. [It] contained a Chinese stove, no oven, two large cauldrons with fire boxes underneath, a ledge about 1.5 feet [0.5 metre] wide on which to place things, a sink without running water. The only equipment consisted of two large frying pans, two family sized copper pots, some galvanised tin pails [of] poor quality, a dozen paring knives, 4 bread knives, a couple of crocks and bowls. Everything else in kitchen equipment — knives, forks, ladles, plates, bowls, pans, beaters, grinders and containers — provided by internees."

There was running water in two of the kitchens. In others, all water used in cooking, cleaning and drinking had to be pumped, carried and boiled in two cauldrons at the far end of mess hall — well away from the kitchen areas.

"Dining room tables and benches [were] badly made of poor wood, difficult to keep from falling apart and difficult to keep clean. Seating space inadequate", resulting in "long queues" and "two and three sittings", for each meal.

"Occasionally, a mop or broom for cleaning was issued by authorities but never without a struggle. Internees furnished cleaning cloths, soap, powder, etcetera where they had it to spare.

"Authorities were given lists of equipment needed in kitchen and for preparation and serving of food. Nothing ever came of this.

"Below is the quantity of food in ounces supplied per day [1 ounce or 1 oz equals 28.3 grams]. Often it was necessary to discard considerable amounts of meat and vegetables [because it was] unfit for human consumption.

"Meat 5 oz, potatoes 10.2 oz, vegetables 13.6 oz, bread 16.6 oz, sugar 0.6 oz, margarine 0.2 oz, fish 0.8 oz, tea 0.1 oz, coffee substitute 0.1 oz, jam 0.03 oz, flour 0.2 oz, oil 0.4 oz," and less than one-eighth of an egg per person a day.

"Actual caloric intake 1905 [one calorie equals 4.855 joules] [68], of which 1175 was from flour in some form.

[68] In the Joy of Cooking, published by J.M. Dent and Sons, London, England 1946, the book discusses current views of caloric intake. It says: "In general and depending also on age, sex, body type and amount of physical activity, adults can use 1700 to 3000 calories a day. Adolescent boys and very active men under 55 can utilize close to 3000 calories a day. At the other extreme, women over 55 need only about 1700 calories. Women 18-35 need about 2000 calories daily. During pregnancy, they can add 200 calories and, during lactation, an extra 1000 calories. Children 1-6 need from 1000-1600 [calories]."

"Calcium [intakes] inadequate. Egg shells salvaged and ground to supply calcium. No milk except as issued by hospital. At highest point, 35 gallons sour milk for 1800 people. Usually 25 gallons per day." [1 US gallon equals 3.785 litres.]

As Dr Wagner shows and I have written in Chapter 5, Wei-Hsien in 1943 was no holiday camp. In my recollection, inmates' conditions worsened in 1944 and 1945.

Finally, to one other matter that has intrigued many about the Wei-Hsien camp. Since the late 1940s, it has been claimed that the US aviatrix, Amelia Earhart, was interned in the camp. Earhart disappeared pre-World War II while on a Pacific journey. It was suggested she was seized by Japanese officials because she had allegedly used her flights to spy on Japanese military preparations on small Pacific islands. The claims say she was later interned with us, hid in the camp hospital and either died there, or was spirited away by the Japanese before the end of World War II and executed.

As I have shown, we lived cheek by jowl in the camp. Never once in the camp or since have I heard from fellow inmates of a top-secret prisoner in the camp or Amelia Earhart [69] being in the camp. None of those I have questioned heard of the story in camp and none has been able to give any credence to the suggestions that we had Amelia Earhart among us. If she was among us, we would have quickly identified her because she, before her disappearance, was one of the world's most photographed women.

[69] The claims are largely based on a telegram received in late-August 1945 by Earhart's husband in the US. The telegram, sent more than a week after the camp's liberation, is reportedly sourced Wei-Hsien and retransmitted via the US Embassy in Chungking to the US. It says: "Camp liberated; all well. Volumes to tell. Love to mother."

#