chapter 3

Growing up in Tsingtao ...

When I was young, Tsingtao was a relatively small but strategically important seaport and industrial centre on the Yellow Sea in north-eastern China. Its strategic importance was heightened by the fact that it had good rail links, growing investment in secondary industry and the port was not prone to becoming as ice-bound in winter as were more northern Chinese ports.

Tsingtao was also a popular destination for visiting warships from various countries ― particularly those of Japan, Great Britain, France and the United States [12].

[12] In the late 1800s, Tsingtao, which is located on the south-east of the Shantung Peninsula, came under German control. The Germans laid out a modern city and attracted heavy engineering and chemical industries to the area. It was from 1899 a free port and the headquarters for regional German naval forces. In 1914, Japan as a consequence of World War I in which it sided with the Allied powers led by Britain and France against the German-led coalition, successfully blockaded Tsingtao port. Japan then occupied the city until 1922. It gave up control of Tsingtao as a result of the Washington Naval Powers conference. Throughout the inter-World War period (1918-1939) Tsingtao's industrial infrastructure grew strongly and the city's layout was noted for its parks and gardens.

Tsingtao was a cosmopolitan city. Many countries had substantial commercial presences there. They included Britain, America, France and Japan. A wide range of non-Chinese nationalities lived and worked there. They included: Russian, German, Portuguese, Italian, Armenian and others such as Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians.

Most of the foreign residents mingled socially and for them there were lots of functions, balls, parties, weddings and other gatherings to attend. Each spring and summer there were many visitors to Tsingtao because it was also a popular holiday resort.

Our house at 14 Second Chan Shan Road, Iltis Huk, had a small bungalow in its grounds to accommodate friends and relatives on visits. Their visits were frequent ― especially in summer. My parents were keen tennis players at the Tsingtao Tennis Club and also went horse riding, played indoor bowls, and went fishing and swimming. They attended civic functions, cocktail parties and other social gatherings. My mother, like most socially active people at the time, was a keen mah-jong player (a Chinese game played with small tiles) and she delighted in `skinning' her opponents – as she used to boast.

My parents frequently had house parties. During these, I was left in the care of one of our two amahs (Chinese female servant). Because I was interested in the fashions of the day, I would make sure that I could observe how the ladies were dressed when they came to the parties. I often longed as a child to be able to wear some of their finery.

We were well-off at the time. My mother was always smothered with furs and diamonds. One of her furs was a catskin coat. I still have a pair of mosaic gold and pearl earrings that my mother said were presented to her father for his wife (my maternal grandmother) by the Czar of Russia. She used to wear them in China but she would not allow me to wear them, saying they were too valuable. I have not yet been able to authenticate their origin.

My father, who we lovingly called Pop, had a stamp collection consisting of a lot of rare and misprinted stamps left to him by his father, who accumulated them during his time as an auctioneer in China around the turn of the 20th century. Pop said later they were so valuable he kept them in a safety deposit box at a Sydney bank. Because I was interested in valuable stamps I asked him several times to get them out of the bank to show me but he refused to do so for fear of them being damaged or lost. A short time after his death in 1969 (at Sydney) I asked my mother about the stamp collection and she told me she had sold it to a dealer in Sydney. When I asked her for the dealer's name she refused, saying: "He told me that I could not use them because the printing on them was faulty. Only 50 of them were any good so he gave me one cent each for them." I was thunderstruck. I said: "What?" She said: "It's all right, they were all printed wrongly, the man said." I still feel sick in the stomach when I recall the price she received for those stamps. The 50 cents Australian was not enough then to buy a packet of doughnuts.

From the time we left China to come to Australia my mother was unhappy. I am sure her experiences in China during the war and the letdown from her lavish lifestyle before the war were strong factors that influenced her gradually building depression during her Australian years. I was a little unhappy too but I put it all behind me and got on with life by working and moving around the world.

Pop would try anything and was resourceful. He assumed the care of his five brothers and sisters following the death of his mother in childbirth which was followed shortly after by the death of his father. His uncle Willie, who was executor of grandfather's estate, apparently did not distribute the assets to Pop's brothers and sisters. This meant my father had to find for them. He was then in his teens.

When his younger sister Grace was about 10, Pop realised she had to be told the facts of life so he bought her a book to explain what it was necessary for her to know. Grace, who is still alive in England and is now aged over 92, told us recently about the book saying: "Your father was so sweet, he came and handed me a book on the birds and the bees, with all these little pictures of flowers and butterflies and birds and said `I think you should read this'."

In 1935, when I was about 7 and Grace was holidaying with my parents in Tsingtao, she cut my long hair into a `bob' style which was becoming fashionable at the time. I thought I looked gorgeous but when my mother came home and saw me there was a big row and she did not speak to Grace for months afterwards. My long hair had been my mother's pride and joy and she used to curl it with rags. I can't blame her for being upset. One good thing was that as my hair began to regrow I was then able to have it in the style of Shirley Temple's [American child film actress of the 1930s and 1940s]. A Shirley Temple-style haircut then was even more fashionable than the `bob'.

As a child, I was principally cared for by our amahs who were responsible for my brother and myself. We became very attached to our amahs. I remember Niong Niong (Chinese for mother) and her successor Da Niong (big or older mother) both very well. Niong Niong was the wife of our cook, Chang. Da Niong never married. Niong Niong and Chang lived in the servants' quarters with their two daughters, Dan and Liang-Ju. I used to play with Dan and Liang-Ju and that is how I learned Chinese.

Niong Niong and her daughter with me.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

Both amahs had maimed feet caused by binding ― known as bound feet. They had difficulty walking. My mother persuaded Niong Niong not to bind her daughters' feet. After the war, Niong Niong's daughter Dan brought her new husband to meet us when we returned to Tsingtao. Emotionally, she hugged and thanked my mother for advising her mother not to bind her and her sister's feet.

The barbaric practice of binding the feet of female Chinese babies was an ancient custom. It was done because some men preferred dainty, small feet in women. The feet were bound shortly after birth with strips of cloth tightly wound around the child's feet. It prevented correct development of the feet. Rarely could the bound women walk without pain and difficulty. My brother and I, not really understanding the painful nature of their artificial disability, used to tease the amahs and run away knowing they could never catch us.

All conversations with the amahs and Niong Niong's children were in the Mandarin-Shantung dialect because they knew little English.

We also had a male house servant whose job was to wait upon the family at table. He wore a long white Chinese gown and white gloves. He also helped about the house, cleaning silver and the like.

Chang was responsible only for the cooking. Each day, my mother told him the menu for the day and he would prepare it. Mum used to go to the markets and buy the meat and vegetables. The markets were in a large pavilion with all the produce on open display. Carcasses of beef and pork hung behind the butcher and mum would pick her desired cut of meat after prodding it with her finger for tenderness and freshness. There was no mutton or lamb sold there. We carried the food home in shopping bags. Shopping, particularly for fresh meat, had to be done almost every day because there was no modern refrigeration. Ice was delivered several times a week by a coolie (a Chinese labourer) carrying it on the back of his bicycle. The ice was wrapped in a bag with sawdust to keep it from quickly melting. The ice kept the contents of our ice chest cool. We made our own ice cream in an ice cream churn, which was quite a tedious process. We used to help the amah and cook with turning the handle of the churn.

Sometimes, my father would drive us to the markets but mum had her own car and most times she drove. Sometimes she took an amah with her. We often had chickens which were brought live to the door, bought and then killed by the cook.

Our normal food at home was roast beef, chicken and pork in a wide range of dishes. These dishes included: chicken in breadcrumbs, chicken in white sauce, schnitzel, German-style sausages and other delicacies such as Russian food. We dined out at least once a week at Chinese restaurants and cooked Chinese-style at home quite often. Chang had been trained by a local German family. He was good with local and exotic dishes and spoke German well.

Often, when my parents were absent from home, I ate with the amah either in the kitchen or squatting on the ground outside. We sometimes ate periwinkles we had gathered at the beach. The cook would boil them in water and we would eat them by picking them from the shells with hairpins which the amah took from her hair and handed to us. I thought it was delicious. I joined them in eating boiled Chinese cabbage with rice water called congee and plain rice and salted Chinese turnip. We shared dried fish and rice.

We had a coolie who did the yard work, sweeping and cleaning. We had polished wooden floors with Chinese carpet squares which the coolie maintained. In those days, it was a common practice to throw used tea leaves onto the floor to attract dust to be swept up by the broom. The broom's brushes were made from sorghum stalks. He also mowed the lawn using a large scythe.

From time to time a man visited and attended to the garden. We did not grow vegetables, only flowers. He helped to scythe the grass and tended our apple and pomegranate trees. We had a grapevine growing over a trellis and we kept a goat from which we got milk. When needed, we bought cows' milk which had to be boiled – as did the drinking water.

We had a `sew sew' woman who regularly came to do the sewing and mending. She made dresses and other clothing for us. She knitted dressing gowns for my brother and me. A tailor came regularly to our house and after measuring up would take orders for my parents' clothing ― dresses and suits. They would either sketch what they wanted or pick it from a (usually American) magazine and he would follow the pattern. After one or two fittings, he would deliver the completed clothes.

Our light clothes washing was done in the bathtub by the amah. She first used a scrubbing board and then rinsed the laundry in the tub. I have not seen a scrubbing board for many years. They were good but a little hard on the fabric. Heavier washing was picked up by a laundry man on his bicycle and delivered cleaned and pressed a day or so later [13].

[13] My family had never seen a home laundry until we came to Australia. My mother and I were astonished to see our first one. We were amazed to discover that Australian homes had a separate room just for washing laundry. Our first had a copper [a large copper pot for boiling dirty clothing] and two tubs. We soon learned how to use it.

Brother Eddie with me at a Tsingtao beach.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

As children, we did not have to do any chores around the house and I spent a lot of time with the amah and cook. I used to enjoy watching the cooking. We sub-scribed to Girls Own Annual and Reader's Digest which I read regularly. I do not remember the Chinese servants ever having annual holidays or days off. I know that occasionally they would get a day or so off by inventing a family crisis. Their children would tell me the truth but I kept that to myself.

I played games with the Chinese children from nearby villages. We played marbles and hopscotch and a game which required us to throw a little bag of sand or dirt into the air and then pick up another bag while catching the thrown bag before it hit the ground. This continued until we had picked up a certain number of bags. I have since learned this game is played in other countries using knuckles obtained from pigs or sheep.

I had a tricycle and later a bicycle. With my girlfriends I would cycle to the beach and to Cherry Blossom park about three miles (five kilometres) away from home. One day our cycling got us into trouble because a law which we did not know about had been introduced requiring all bicycles to be registered. Because our bicycles were not registered we were pulled up by the police. They threatened to confiscate our bicycles but I was able to persuade them not to – in Chinese. After that experience we kept fairly near home with our bicycles.

As children we used to dress up and play ladies with dresses and shoes given to me by Madam de Roche, a French lady who ran the Bel-Air hotel which was next door to our house.

On Sundays after church we went to the International Club where I usually had a hot dog roll and a glass of sarsaparilla. That was a real treat for me and I liked to sit and watch the hats worn by the ladies. The club attracted local European residents and was popular. There were facilities for games such as mah-jong, meals, a ladies lounge and men only section [14].

[14] Employed at the club were George and Shura Kuzmenko, who migrated to Australia after World War II. The International Club after the war became the temporary headquarters of the American Red Cross where I worked for a while.

Sometimes, I used to go into town, which was several miles away, by rickshaw with grandmother. The rickshaw coolie for a few Chinese cents would pull the two of us into town. It was hard work for the coolie who always had a little towel to wipe his sweat off as he went up hills. Rickshaw coolies did not grow old and we were told they died young from hardening of the arteries.

On other occasions, we travelled by a horse-drawn carriage which seated about six people. The carriages were multicoloured with white frills around the seat cushions and white upholstery. Usually they had two white horses with the driver sitting on the top at the front. I used to enjoy these rides. The carriages were hired for a small amount of money.

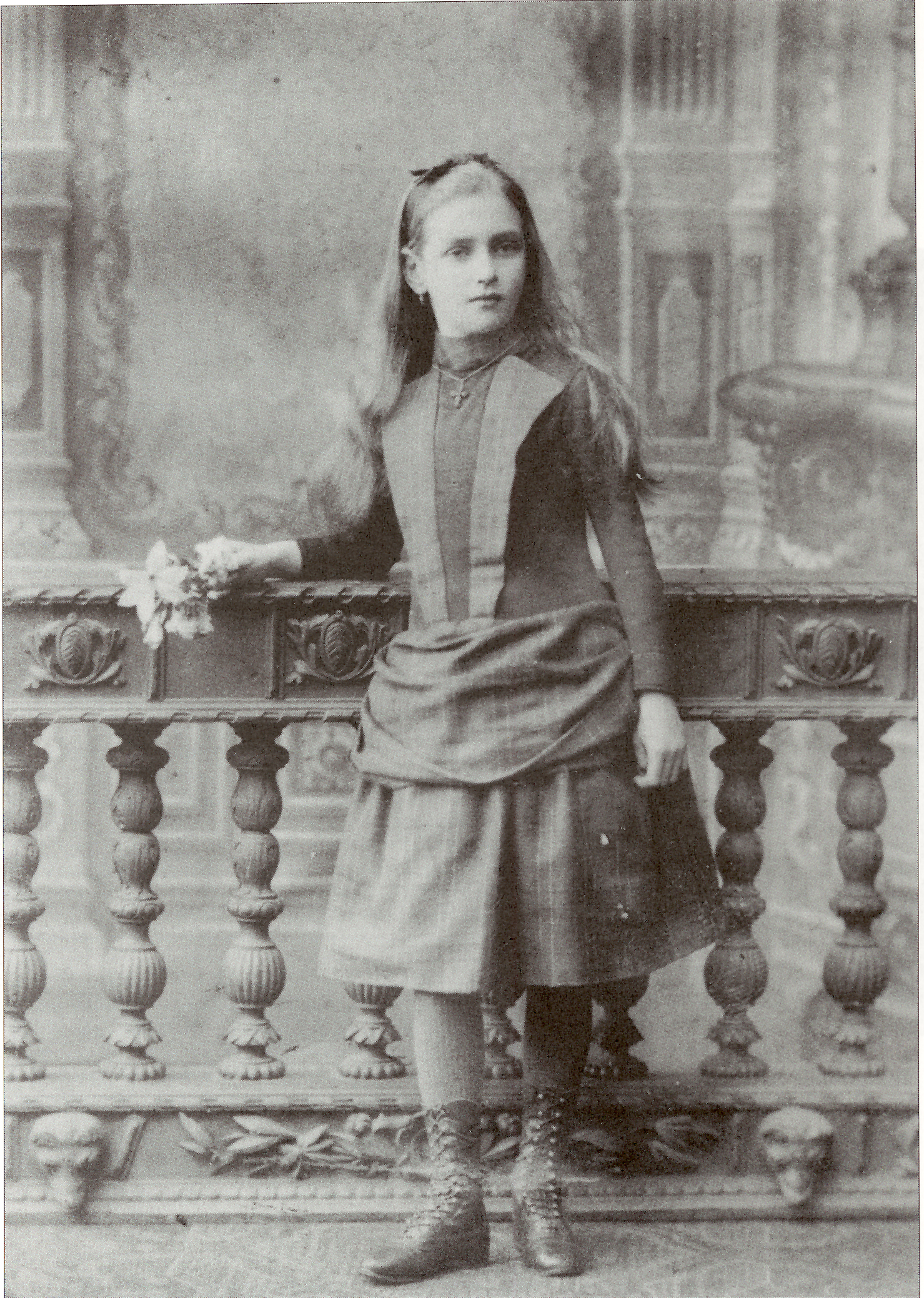

My maternal grandmother as a child.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

Grandma, my maternal-grandmother (a German born in China), from whom I learned German, spent a lot of time with us. She used to live in a house at Tsingtao and later moved to Dairen (now known as Dalian). I sometimes stayed with her when my parents were away from Tsingtao. Grandma used to make Russian bortsch (beetroot with cabbage soup), pelleminis (minced beef dumplings in soup), cabbage rolls, rissoles and sell them. Russian and some German shopkeepers would visit with little containers and take away her cooked food for their own meals.

My maternal grandparents had been wealthy but grandfather Vladimir Booriakin lost everything in a financial crash. While grandmother and her four children were holidaying in Italy he shot himself. Despite being forced into a difficult situation by the death of her husband, grandmother was a cheerful woman who worked hard to support her children. In Tsingtao, she lived with her sons Boris and Andre. Boris Booriakan now lives in Sydney. After World War II, André lived in China, Russia and the US where he died in the 1990s.

My mother was educated in Italy and France and went to finishing school in Switzerland. She spoke French, Italian, German, Russian, Chinese and English. She always told me that as a child she had a special Russian nanny named Alna Palna, a large woman. They also had other servants including a coachman with an ornate two-horse carriage with bells around the horses' necks. Mum said one of her most pleasant memories as a child was travelling in the carriage through the snow with all her furs and the bells ringing.

Mum must have been a dreamer as a child because she often used to tell me about the time as a very young child she saw a Douglas Fairbanks movie in which there was a flying carpet. She attempted to emulate the flying carpet scenes. She was found by a neighbour sitting on a mat on the roof of her house waiting to fly off.

I know she was a romantic. Sadly, she always said to my father: "When you die, I will die." This, she did by progressively losing interest in life after his death in 1969. Nothing we could do would cheer her up and she wasted away and died five years later. She actually went to bed after Pop's funeral and said: "Pops is dead, I am going to die too." She stayed in bed for three days but when she found herself still alive she got out of bed and went on living. But she never got over Pop's death. They had been through so much together.

At school, I learned French which was compulsory. I spoke in French to some of my school friends. I was fluent in English, Russian, German and Chinese. There were many different schools in Tsingtao. There were English, American, Russian, German and French schools. My parents sent me to the Holy Ghost convent run by French, German and American nuns of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary order. I had a traditional Roman Catholic schooling. We observed Holy Days, said our prayers and went to confession and communion. Because our cook was not Catholic, I was often given sandwiches containing meat for my Friday school lunch. A nun checked the day scholars' lunches each Friday to ensure they complied with the tradition of not eating meat on Fridays. Whenever my brought lunch was found to contain meat, it was confiscated by the little French nun whose duty it was to examine the lunches. She would then say: "Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, Mademoiselle Cooke, vous allez à la salle à manger." [My God, my God, Miss Cooke, you go to the dining room.] And, she would escort me, much to my joy, to the dining room with the scholar boarders to have a seafood lunch. This suited me fine because I love seafood. In our home, we did not observe meatless Fridays – except for Good Friday, because my mother was Russian Orthodox and somewhat lax in observing the rituals of the Catholic faith that I was learning at school and from weekly attendance at mass.

Once, I was found to be chewing gum in class. My teacher made me stand in front of the blackboard for the rest of the lesson with the wad of chewing gum stuck to the end of my nose. I was so embarrassed. I did not chew gum at school again.

On another occasion I went to class with my hair curled. It was normally fairly straight but the previous night my mother had curled it with strips of rag because I was going to a party after school. Everybody at school noticed my curled hair including a nun. She took me to a tap, wet my hair and combed out my curls. I received a lecture that I must not exhibit vanity by curling my hair because it was a sin.

My father usually drove me to school which was several miles from home. On most occasions I caught the school bus home but I would have to walk the last two miles (3.2 kilometres).

Quite often on the way home, I saw the swaddled dead bodies of baby girls who had been abandoned by their Chinese parents. The mothers would leave them on the ground in parks and vacant land. Sons are much preferred by the Chinese over daughters because they believe male children can support their parents when the parents grow old. Daughters were thought by poor Chinese parents to be a burden because a dowry had to be paid when they married and the bride then became the property of her husband's family.

On the way to school, I sometimes saw the bodies of old people — usually women — who had committed suicide overnight by hanging themselves from trees. Life was hard for many Chinese people. It was especially hard for those with nobody to care for them. Suicide was sometimes their unfortunate decision. When coming back from school on the same day, I would always see that the body had been partly lowered until the knees touched the ground. Before the body, little bowls of rice and fruit had been placed with a bowl of sand containing burnt incense sticks. Homage had been paid to the dead person by some person or persons I never saw. Next day the body was usually gone.

The Chinese people in our area seemed to consist of three classes. The very poor farmers who worked in the fields lived in the villages with their wives and families in mud huts with dirt floors. They kept pigs and chickens for their own use and grew vegetables in their little yards. The women and children used to go onto the rocks at the beach and collect seaweed to bring home and cook. They grew sweet potato which they used to slice up and dry on their roof tops and then store for winter meals. They had awnings above the front door and they did their cooking either there or out the back on wood burning stoves. Coolies, who did menial labour, usually came from these families.

The next class of people owned little shops such as bicycle repair shops, grocer shops, and shops selling woven cloth. These people usually lived in better houses built of brick or timber. It was from this class that municipal employees, office workers and other middle class workers were usually drawn.

Then, there were the very wealthy business people who lived in the affluent residential areas. Their homes were often big and beautiful. Many Europeans socialised with this class. These Chinese usually owned the restaurants and often were well-educated. Chinese businessmen and government officials also lived well in large houses. Many of the Chinese homes had little shrines with burning joss sticks and offerings of fruit and other food.

Our home had flush toilets but the Chinese villagers' homes did not. They collected human waste and used it to fertilise their gardens. No doubt this practice contributed to many illnesses. To protect ourselves from diseases, we always washed all our fruit and vegetables in a Condy's crystal [potassium permanganate] solution unless the vegetables or fruit were boiled during cooking.

When I was about 12, I became ill with typhoid fever. I was ill for a long time. At about the same time, my brother became infected with tuberculosis, which we believed he got by smoking our cook's discarded cigarette butts. He was eventually cured. One of the suggested cures involved him having to drink warm lard (pig's fat) mixed with cocoa. Later in Australia we were told that the treatment would have given my brother a high energy diet at a time when his body was being attacked by the disease.

Europeans and other non-Chinese nationalities lived in various parts of Tsingtao. Only the Japanese congregated in a specific area.

A strong memory of the pre-war Japanese community is their wonderful toy shops crammed with celluloid dolls, tin cars, toy motorcycles, brightly coloured glass animals and marbles.

With my friends, I went to the movies in Tsingtao regularly. The movie house was named Fooloozoo and we used to sit in the dress circle upstairs. There was also the Star Cinema. I remember Deanna Durbin, Jane Withers, Shirley Temple and Clark Gable (cinema actors) for example. We always got free entry because my father was connected with the cinema.

I had many girlfriends of all nationalities in Tsingtao. They are now scattered all over the world but I still meet some of them and correspond with them. Some are now in Australia, America, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong and Canada. One of my best friends was an Italian girl named Licia Pezzini [15]. She and her parents looked after a lot of our possessions during the war. Despite the fact that many Italian nationals were interned by the Japanese after Italy capitulated to the Allies in World War II, Licia and her family were not imprisoned.

[15] Licia (nee Pezzini) Childress. Now lives in California.

From time to time I would find stray dogs in the street. Because I love animals I would bring them home with me. Unfortunately, we could never keep them because I was told all the strays were infected. Consequently, I had to be disinfected because I had hugged the strays. For disinfection, I had to use lysol and wash thoroughly.

One of the dangers from such dogs was rabies [sometimes called mad dog disease or hydrophobia]. I have seen rabid dogs. Once, when my father was doing the garden, a stray rabid dog ran into our yard. It was not a large dog. It was red and was frothing at the mouth. It attacked our two pet dogs – a West Highland terrier and an Alsatian. As Pop separated them the rabid dog bit into his long rubber boots. The police came and shot the rabid dog. Dad was told by the police to destroy our two dogs because they had been in contact with the rabid dog.

I cried when he took them up into the hills to shoot them. But he came back with the West Highland terrier saying that he didn't have the heart to shoot her. The West Highland terrier survived to die of old age. Her name was Aster. My parents got Aster during a visit to Shanghai. There, she was about to be destroyed because she had a large scab on the end of her nose about the size of a ping-pong ball which was thought to be incurable. My mother eventually got rid of the scab by applying linseed oil.

I was not aware of problems between the Chinese Government and the Japanese until one day we noticed members of the Chinese community passing our home heading for the hills out of town. My father said they were going into the hills to dig shelters because they knew there was going to be war.

That didn't worry me at the time. Life went on with plenty of friends. One was Belgian, Johnny de Zutter. Johnny and his family [16] was later interned by the Japanese in the same camp as my family.

[16] The de Zutter family settled in the US after the war.

About this time, Dad was driving me home and I had an amazing accident. I fell out of the car when the front seat door came open as he turned a corner. I rolled out and he didn't notice my absence until he got home. He got a tremendous shock and came back to look for me. He found me crying from a grazing.

#

Niong Niong and her daughter with me.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

Brother Eddie with me at a Tsingtao beach.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

My maternal grandmother as a child.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.