chapter 6

Liberation

The one morning that will always remain in my memory was the morning I heard the sound of aeroplane engines and Pop calling out to my mother: "Vera, Vera, come quick. Look, look, they're dropping something."

We ran outside and saw an aeroplane flying overhead. It was lower than any aeroplane we had seen before. This was something completely new for us. Although we had seen tiny specks high in the sky several times before we had never seen an aircraft so close.

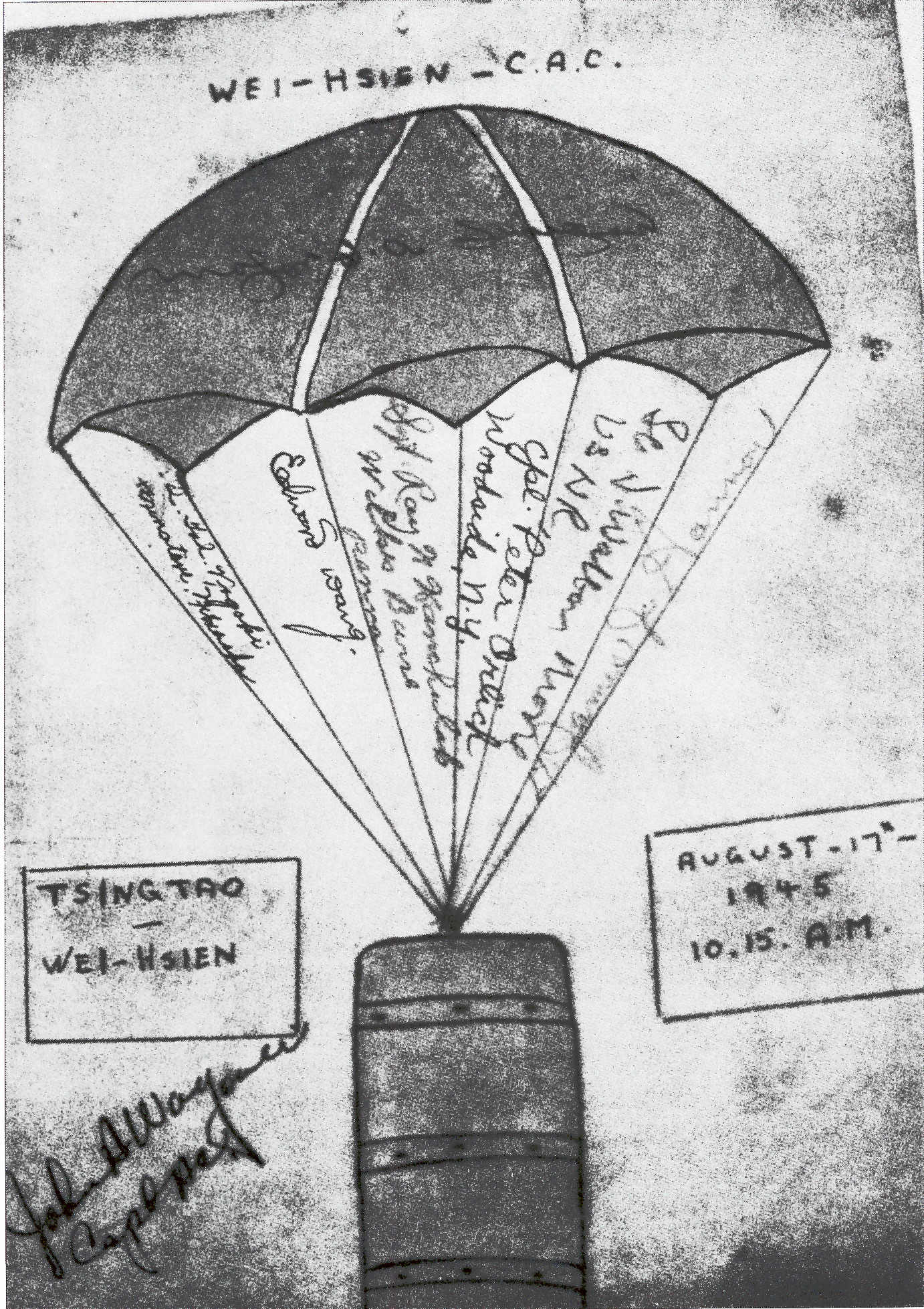

August 17, 1945 was a clear day at Wei-Hsien. From the low-flying aeroplane, I suddenly saw objects dropping and parachutes opening [45]. My father called out: "Oh look, they're dropping food or something for us." We watched with amazement. Then Pop said: "Oh, they're men. They're moving. Look at their legs. They're men."

[45] The first wave of parachutists landed at 10.15 a.m. on August 17, 1945. The time and date was recorded by one of the parachutists in my autograph book. All the first-wave parachutists signed my autograph book.

Bradbury family collection.

We all realised that something big was happening and we ran past the church towards the camp's entrance. Many ran out the camp's gates but I didn't. To be honest, I was frightened of the Japanese guards there. The guards stood at their posts. They were looking at the parachutes too. They seemed stunned and taken completely by surprise. Many of our young men ran right past them and the guards did not try to stop them. Everybody was calling out: "What's happening? What's happening?"

The parachutists landed just outside the compound. I ran full pelt up to the gate to see what was happening. At the gate, I saw these armed and uniformed parachutists being carried shoulder-high by the inmates into the camp. As the parachutists were carried to the gate, I realised they were American. One of them was a Japanese-American named Tad Nagaki. He went up to a bewildered gate guard, slapped him on the back, and said: "Now, what do you think of your Nagasaki?"

The parachutists landed just outside the compound. I ran full pelt up to the gate to see what was happening. At the gate, I saw these armed and uniformed parachutists being carried shoulder-high by the inmates into the camp. As the parachutists were carried to the gate, I realised they were American. One of them was a Japanese-American named Tad Nagaki. He went up to a bewildered gate guard, slapped him on the back, and said: "Now, what do you think of your Nagasaki?"

The Japanese guard stood there dumbfounded. Understandably, we did not know anything about Nagasaki, one of two Japanese cities which were targeted with US atomic bombs [46] in August 1945. I wonder now whether the confronted Japanese guard knew anything of the atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki.

[46] In retrospect, there is no doubt that the war was lost for the Japanese well before its official ending. The use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki suddenly and unexpectedly stopped a lot of killing and casualties which would have occurred if the Japanese had continued to resist surrender to the Allies. I believe in the dropping of the bombs because it saved many lives by quickly ending the war. Among those lives saved were the people in the camp with me.

From the camp entrance, the American soldiers led by Major Stanley Staiger [47] then walked towards the Japanese officers' quarters. Some guards ran toward the quarters but they did not try to stop the Americans. The guards then abandoned their positions at the gate. There was a big commotion as the camp inmates realised their imprisonment was ending. Everybody was unbelievably excited.

[47] Among the parachutists was US Army Lieutenant James Jess Hannon. Hannon, when serving with the US Parachute Infantry, was captured at Anzio, Italy, during the war. He was then held as a German prisoner of war at five camps. He escaped from the last one in Poland and made his way to Romania where he was rescued by the US Air Force. He was subsequently posted as an intelligence officer and assigned to US Special Forces in Kunming, China. The parachutists took off from Hsian airport, China. Hannon was injured in the landing and had to receive attention at the camp's hospital. In a letter about his experiences, he writes: "Wei-Hsien Prison Camp and the condition of the prisoners was not comparable to anything in my experience. They were indeed fortunate, apparently unaware that prisoners of German and Japanese forces throughout the areas they controlled experienced monumental and unparalleled horrors. Most of the [US parachute] team stayed at the camp several days."

Letter from James Jess Hannon, Yucca Valley, California dated February 17, 1998.

Family documents. Bradbury family collection.

In February 2000, Hannon was quoted in an interview that he had written a film script about his war experiences and he was having talks with film producers about the possibility of the script being used in a film.

Associated Press, February 21, 2000.

At the officers' quarters, Major Staiger walked with two Japanese guards to the commandant's quarters. The Japanese commander met Major Staiger and quickly surrendered his sword to him [48].

[48] The quick surrender of the Japanese suggests they had been advised by their command of the Allied plans to liberate the camp. Some people who were in the camp have since claimed that the camp inmates' leadership knew of Japan's capitulation.

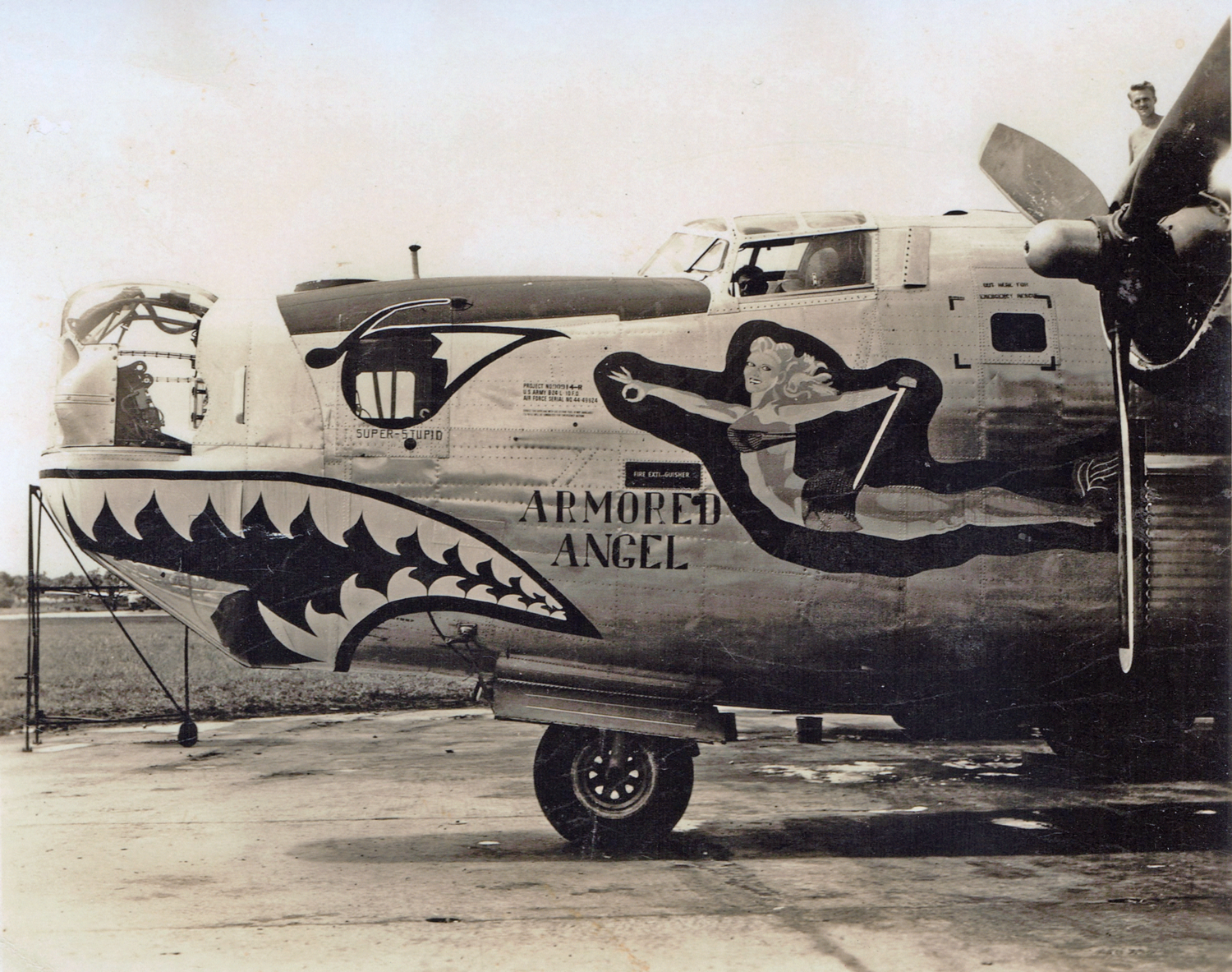

Overhead, the B-24 US aeroplane from which the US soldiers parachuted kept flying around in circles. The aeroplane flew so low I could see its name, The Armored Angel, and a painting of a glamour girl in a two-piece costume on the fuselage. A short time after the Japanese commander's surrender, a canister was dropped from the aeroplane. The canister contained supplies for the parachutists. It wasn't long before other American aeroplanes came and dropped many canisters [49] together with leaflets warning us not to overeat.

[49] Dropped with the first wave of canisters were leaflets which were headed:

"ALLIED PRISONERS".

It reads: "The JAPANESE Government has surrendered. You will be evacuated by ALLIED NATIONS forces as soon as possible. "Until that time your present supplies will be augmented by air-drop of U.S. food, clothing and medicines. The first drop of these items will arrive within one (1) or two (2) hours.

"Clothing will be dropped in standard packs for units of 50 or 500 men."

The leaflet then outlines the clothing, medicines and food to be delivered. Subsequent drops came from aircraft flying from as far away as Okinawa, Saipan and Guam. Aircraft used for the drops included B-29 Super Fortresses.

Family documents. Bradbury family collection.

Swiss consul's map of the camp and the leaflet the US dropped informing us of coming food and clothing supplies delivered by parachute.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

With glee, we fell upon the canisters and found they contained wonderful things. Cardboard cartons of tinned food, clothing, medical supplies, toiletries and even boot polish. From that moment, we felt we belonged to America.

The canisters were large and also contained food and clothing in packs designed for use by hundreds of men. There were trousers, shirts, shoes, towels, sewing kits, soap, razors, toothbrushes and insecticide. The food consisted of cans of soup, fruit juice, vegetables, field survival rations, coffee, sugar, milk and cocoa. And, there was candy, chewing gum, cigarettes and matches. The packs were made up for military personnel, not for women and children, but that didn't worry us at all. We all cheerfully shared in the bounty.

US military aircraft dropping supplies to camp taken by fellow prisoner.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.

One canister landed near a village and the villagers received the contents. A day or so later a young Chinese boy was brought into the camp very ill. He had eaten some of the boot polish thinking it was food. Our doctors treated him and he recovered. Some Chinese people were injured because they were struck by falling canisters. Because some canisters contained knitting needles and wool some of the women inmates began knitting clothing.

I do not remember where the American soldiers were accommodated during the following nights but I presume it was in the Japanese quarters. Pop told me the Americans lined up the Japanese and Pop walked up to Captain Yumaeda, shook his finger at him and said: "You are a war criminal." As I search my memory now, I cannot recollect what, if anything, happened to any of the Japanese officers or guards. They just weren't there any more. I certainly did not worry about them or even give them a thought. Had anything untoward happened to them I would have been told about it.

On the first day of our liberation we ate our normal rations but from then on we dined well. The first lavish feast consisted of bread, butter, cheese, jam and everything else together despite the warnings from the American soldiers not to overeat. As it turned out we could not eat much. We had been starved for so long that our stomachs had consequently shrunk. It therefore took me two days to eat my first lavish meal but even then we didn't waste anything. We always saved the leftovers for the next meal. As the days passed, more US soldiers arrived in trucks. There were many of them. They helped with the running of the camp and everything went well. The soldiers must have been technicians because they got everything working in the camp including supplies of hot water in abundance.

Once, I welcomed some of the soldiers with a kiss and one of them said: "Wait there, wait there, put some lipstick on, I want my pals to see it." I said: "I don't have any." He said: "Here's some." He produced two tubes of lipstick which I applied and then kissed him on both cheeks leaving noticeable marks. He went off happily to show his friends. I gave the lipstick to my mother. I did not begin to wear lipstick until I was in my 20s.

We really knew we were liberated when we were woken one morning by loudspeakers all around the camp blaring the song: ‘Oh, what a beautiful morning’. From then on it was the signal every day to remind us that we were free again. What a lovely feeling and a lovely song. I shall never forget it or any song from the stage musical Oklahoma. They were constantly played over the loud-speakers.

During this period, Tsolik Baliantz and I got hold of some parachute material which was pure silk and extremely strong. She made me two blouses and a skirt from the material. One white blouse and one red skirt and blouse. She used one of the camp's portable sewing machines that my mother had used earlier to make me a pair of shorts and a top out of an old dress.

After liberation, every family was issued with cartons of tinned food from the canisters. There was no necessity to cook ― everything was prepared. Cheese, butter, jam, corned beef, tongue, Spam (a brand of canned processed luncheon meat) and chipolata sausages. They were all packed in khaki-green coloured cans. There were also biscuits that the American soldiers called dog biscuits. The Americans didn't forget anything in their food parcels. The parcels even had little can openers. Among the parcels came plenty of cigarettes. So mum, and I think my father, took up smoking again.

Shortly after the Americans' arrival, a news board was set up and every day there were news items, mainly for the American troops. They reported baseball game results and stories about movie stars. I copied some of these articles telling me about a world I didn't know. I still have news reports [50]. Radios arrived in the camp [51] - supplied by the Americans - and we often listened to the broadcast news. Pop was a member of the camp's news committee because he had been a Reuter's news agency contributor from Tsingtao before the war. He helped produce the news sheets posted on the news board.

The adults had to attend meetings chaired by American officers where they were told of the progress in returning us to our homes. They told us to be patient because it would take some time. For my family it took about two months. The American civilian internees were the first to go. I know some of them declined repatriation to the United States because their homes were in China and they wanted to stay there. As for my family, the only home we knew was Tsingtao and that's where we wanted to go. I don't remember being impatient to go home because I started to enjoy myself. No more being dragged out into the open for roll call. There were dances every Saturday night with the soldiers. The American soldiers were extremely polite and well-mannered. They appeared strong and healthy. Everybody liked them. We rightly regarded them as our saviours.

Inevitably, I got into trouble with my boyfriend, Brian Clark (1923-1988), for dancing with the Americans. He never spoke to me again. After the war Brian [52] worked in England, Sweden, India, Brazil, Argentina and Canada where, sadly, he died of cancer.

[52] Obituary notice for Brian Harry Thomas Clark, born Shanghai, died North Vancouver, June 2, 1988. Bradbury family collection.

I did not leave the camp for short excursions into the local neighbourhood after the liberation. To my mind, there was nothing to see. Just miles and miles of open fields and farms devoted mainly to cropping. For the younger children, schooling continued. Because I had finished high school I still had to do my camp committee-appointed chores. However, there was a big difference ― a difference in morale among us. We had music all day and we could have hot showers whenever we wanted them. And, we could move around freely and visit friends at night. Above all, there was plenty of food. The American food parcels were brought in regularly. Fresh vegetables came in from the Chinese. For reasons I have never fathomed, we still didn't get any rice.

Because we had no suitcases for our belongings, we accumulated cartons from the food parcels to take our meagre belongings back to Tsingtao. We didn't have much at all. I just had my camp souvenirs. Prized among them is a large collection of signatures which include the signatures of the parachutists [53] and many of the camp inmates.

#

Bradbury family collection.

Letter from James Jess Hannon, Yucca Valley, California dated February 17, 1998.

Family documents. Bradbury family collection.

In February 2000, Hannon was quoted in an interview that he had written a film script about his war experiences and he was having talks with film producers about the possibility of the script being used in a film.

Associated Press, February 21, 2000.

"ALLIED PRISONERS".

It reads: "The JAPANESE Government has surrendered. You will be evacuated by ALLIED NATIONS forces as soon as possible. "Until that time your present supplies will be augmented by air-drop of U.S. food, clothing and medicines. The first drop of these items will arrive within one (1) or two (2) hours.

"Clothing will be dropped in standard packs for units of 50 or 500 men."

The leaflet then outlines the clothing, medicines and food to be delivered. Subsequent drops came from aircraft flying from as far away as Okinawa, Saipan and Guam. Aircraft used for the drops included B-29 Super Fortresses.

Family documents. Bradbury family collection.

Swiss consul's map of the camp and the leaflet the US dropped informing us of coming food and clothing supplies delivered by parachute.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

US military aircraft dropping supplies to camp taken by fellow prisoner.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo.