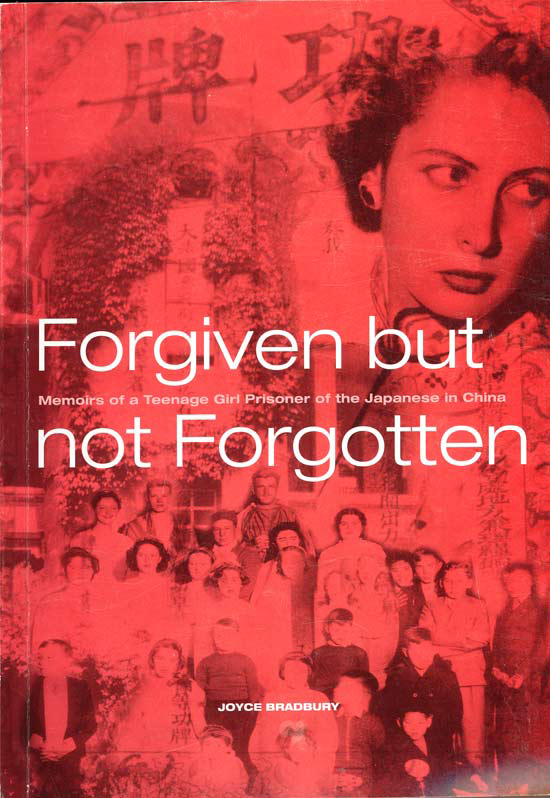

- by Joyce Bradbury, née Cooke

Chapter 5

[excerpts]Teenage prisoner of the Japanese

Our group was the first Japanese internment prisoner batch to arrive in the Wei-Hsien camp and thus we bore the brunt of the camp’s initial cleaning up.

As the days went on some 500 Catholic priests, brothers and nuns arrived together with clergy from a diverse mix of other denominations. About 1500 more civilian internees were also brought to the camp. For the first few weeks we had a big clean-up and committees were formed to set up and staff schools, the hospital, a bakery, a shoe repair shop and kitchens.

As the days went on some 500 Catholic priests, brothers and nuns arrived together with clergy from a diverse mix of other denominations. About 1500 more civilian internees were also brought to the camp. For the first few weeks we had a big clean-up and committees were formed to set up and staff schools, the hospital, a bakery, a shoe repair shop and kitchens.

No clothing was issued by the Japanese during the next three-and-a-half years. As children grew out of clothing it was swapped at the exchange stall set up specially, which we called the White Elephant Exchange.

Internee arrivals trickled in from many parts of Japanese-occupied China. Many came from Tientsin (now called Tianjin), Peking, Chefoo and Tsingtao. Among the adults were professors, teachers, scientists and doctors. There were tradesmen, including butchers, bakers and carpenters, and ordinary businessmen. There were single men and women and many married couples with and with-out children.

Most of the prisoners were of British and American nationality. There were Eurasians and Asians from other countries. There were several Chinese prisoners including an American called Mr Chu. He was tall with an attractive part-Chinese wife. The criterion for internment was citizenship of countries with which Japan was at war but the Japanese interned some who were from neutral countries. Besides the British and Americans, the nationalities in the camp on June 30, 1944 [21]

21 — List of internees dated June 30, 1944 giving names, marital status, nationality, age, sex and occupation. Bradbury family collection. Pamela Masters in her memoir The Mushroom Years, published 1998 by Henderson House Publishing, Placerville, California, writes of at least one French national acquaintance in the camp. However, the list of internees mentions no people of French nationality. See Further Reading.

included Australians [22],

22 — The number of Australians and New Zealanders in the camp list of internees appears disproportionately high compared to the other major nationalities ― British and US. Most of the Australian males were either missionaries or businessmen. Analysis of the countries where the Wei-Hsien internees settled after liberation suggest that Australia and New Zealand took a disproportionate number of them. This latter observation is based on address lists I have been given at international reunions of camp inmates. Bradbury family collection.

Cubans, Greeks, Belgians, Iranians, South Africans, Canadians, Poles, Portugese, Dutch, Norwegians, New Zealanders, Uruguayans, at least one German who apparently also had American nationality, Filipinos, Palestinians, Panamanians and some Russians. The age range of the internees was wide. The eldest internees in mid-1944 were a missionary couple both aged 86. The youngest internee was a one-month-old infant. Because so many school-children had been brought to the camp, there was a disproportionate number of children at the time the list was compiled.

Some of the imprisoned Catholic clergy belonged to strict religious orders which meant their lives were lived in monastic silent contemplation under sparse conditions. They were rounded up by the Japanese and brought into the camp. As my family members were already camp inmates we saw their arrival. Some of these monks had long hair and beards which they were forced to remove. I remember some of them being handsome young men when we saw them the next day, clean shaven, hair trimmed, wearing donated shorts and shirts.

Many of them gazed about in wonder during their first days in the camp but they soon became friendly with the young girls and boys in the camp, of which there were many.

As we began to settle down the various committees allocated duties to every-body over the age of 14. Doctors and nurses were assigned to hospital duties and caring for the health of people while tradesmen worked in the carpentry and other shops. In general, the women had to peel vegetables and the men worked in the kitchens irrespective of their former callings.

The clergy also worked. They performed kitchen duties, stoked hot water boilers for the showers and pumped water which had to be done 24 hours a day. They also helped with heavy work such as lifting when required. One Catholic priest, Father Schneider, was formerly a shoemaker and he was put in charge of the shoe repair shop. Some of the nuns worked in the kitchen, cleaning vegetables, and also taught in the schools alongside Protestant missionaries. Some nuns nursed and some volunteered for the terrible job of clearing overflowing toilets, which they did with grace and dignity. The nuns wore veils over a stiff cloth frame called a ‘coif’ on their heads when they first arrived. After a while, they dispensed with the coifs and just wore a veil pinned to their hair. Many of the Protestant clergy had added tasks. They had to tend to the needs of their families, of which there were quite a few.

Everybody I knew worked hard for the benefit of the whole camp and I am not aware of any problems with persons not pulling their weight. There were four kitchens and dining rooms. Because of the food supply situation, it was a big job trying to satisfy the hunger of the inmates. Sadly, that was never really achieved. My father, a qualified accountant, was given cooking duties in a communal dining room where meals were cooked and served in relays. Mum also worked in the kitchen and made craft goods.

...

[further reading ...]:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/ForgivenForgotten/Book/ForgivenNotForgotten(WEB).pdf

#