- by Langdon Gilkey

CHAPTER I

Into the Unknown

The letter arrived in late February, 1943, at the door of the house I shared with five bachelor teachers in Peking. Rumors had been going around for weeks that the Americans and the British who were then in Peking would be sent “somewhere to camp.”

Some said we would be shipped to Japan; some said Manchuria; some, a Chinese prison. These stories increased in volume and in flavor; something was going to happen soon, we knew. So it was with anxious concern that I tore open the long, white envelope.

Some said we would be shipped to Japan; some said Manchuria; some, a Chinese prison. These stories increased in volume and in flavor; something was going to happen soon, we knew. So it was with anxious concern that I tore open the long, white envelope.

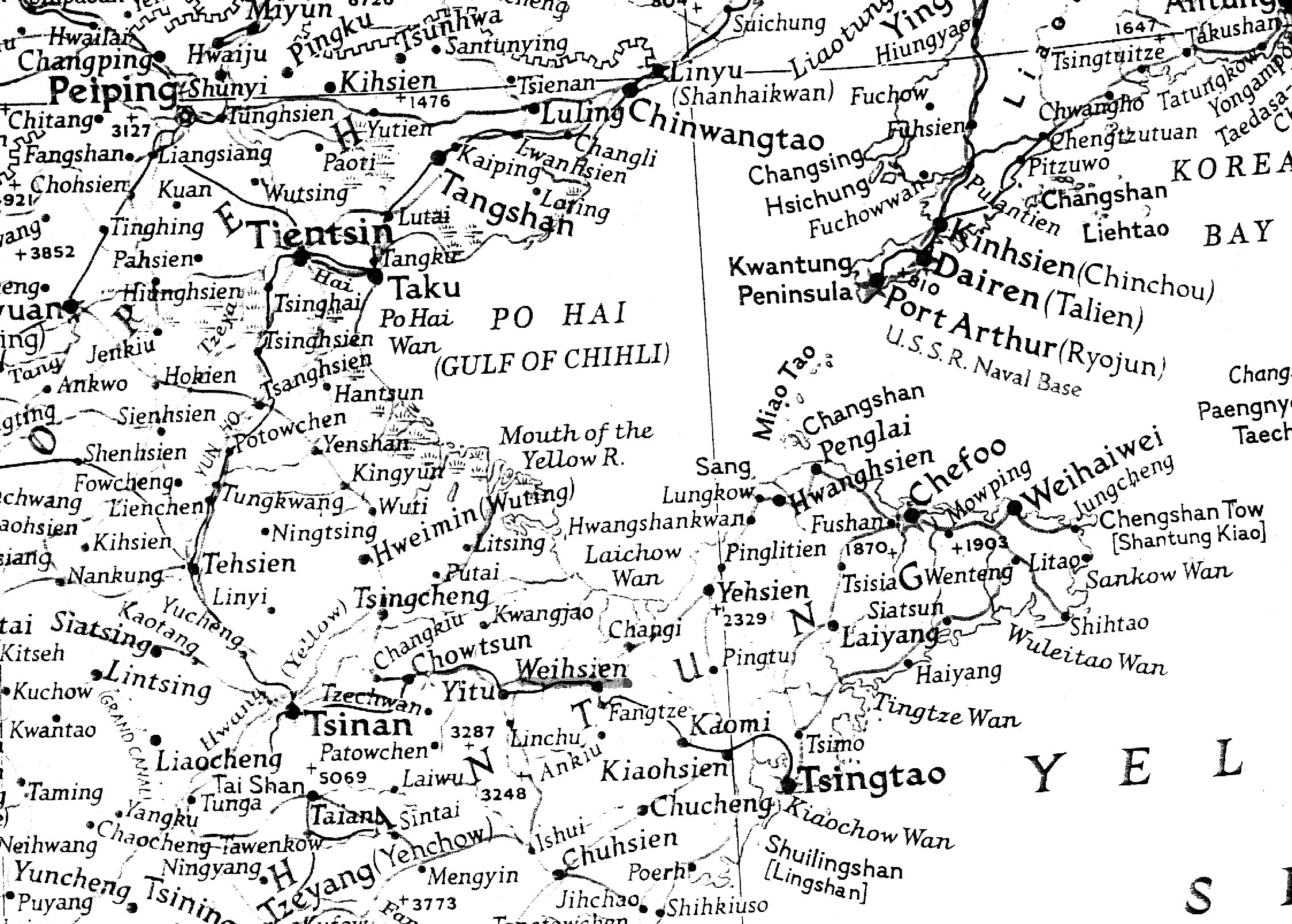

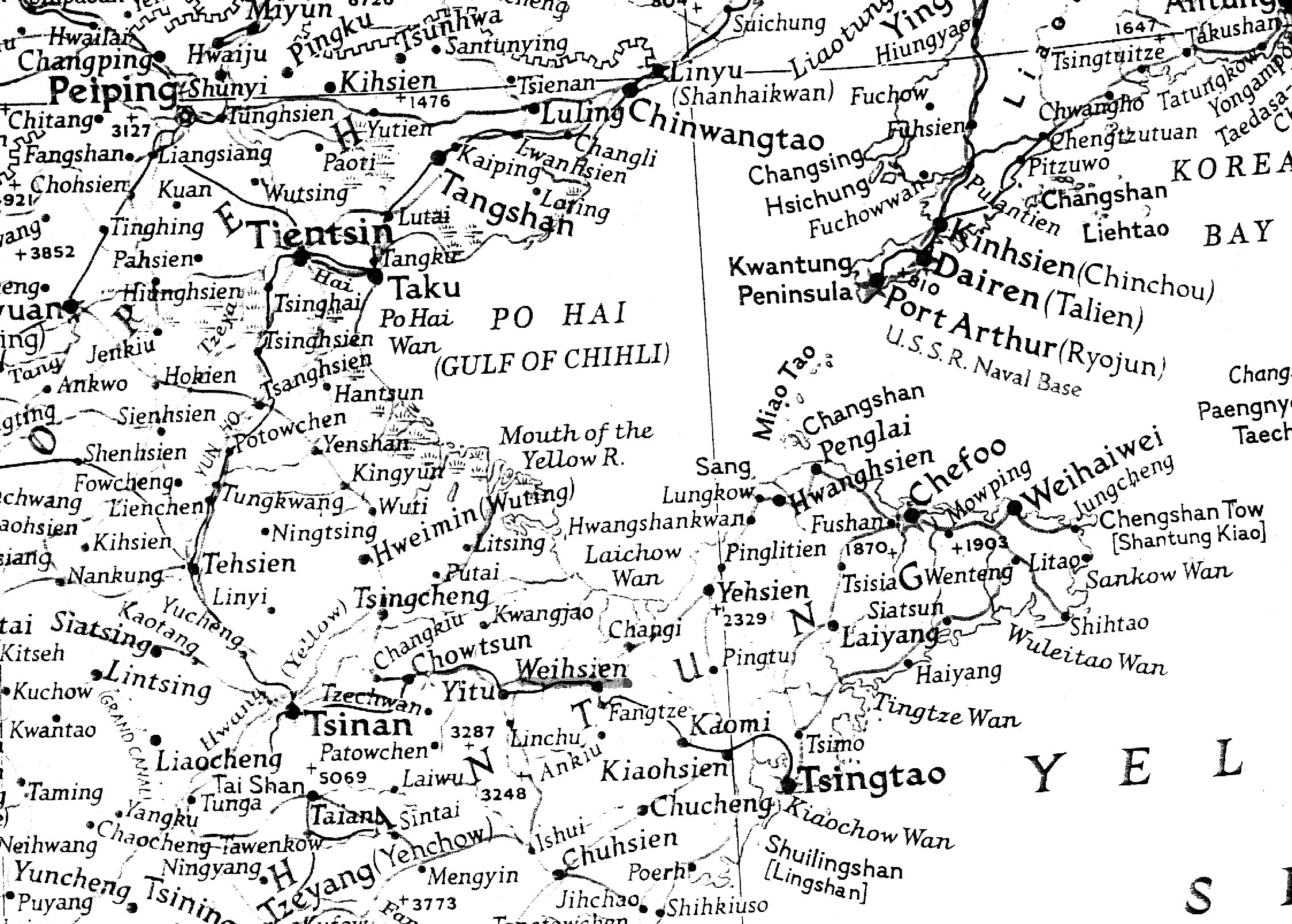

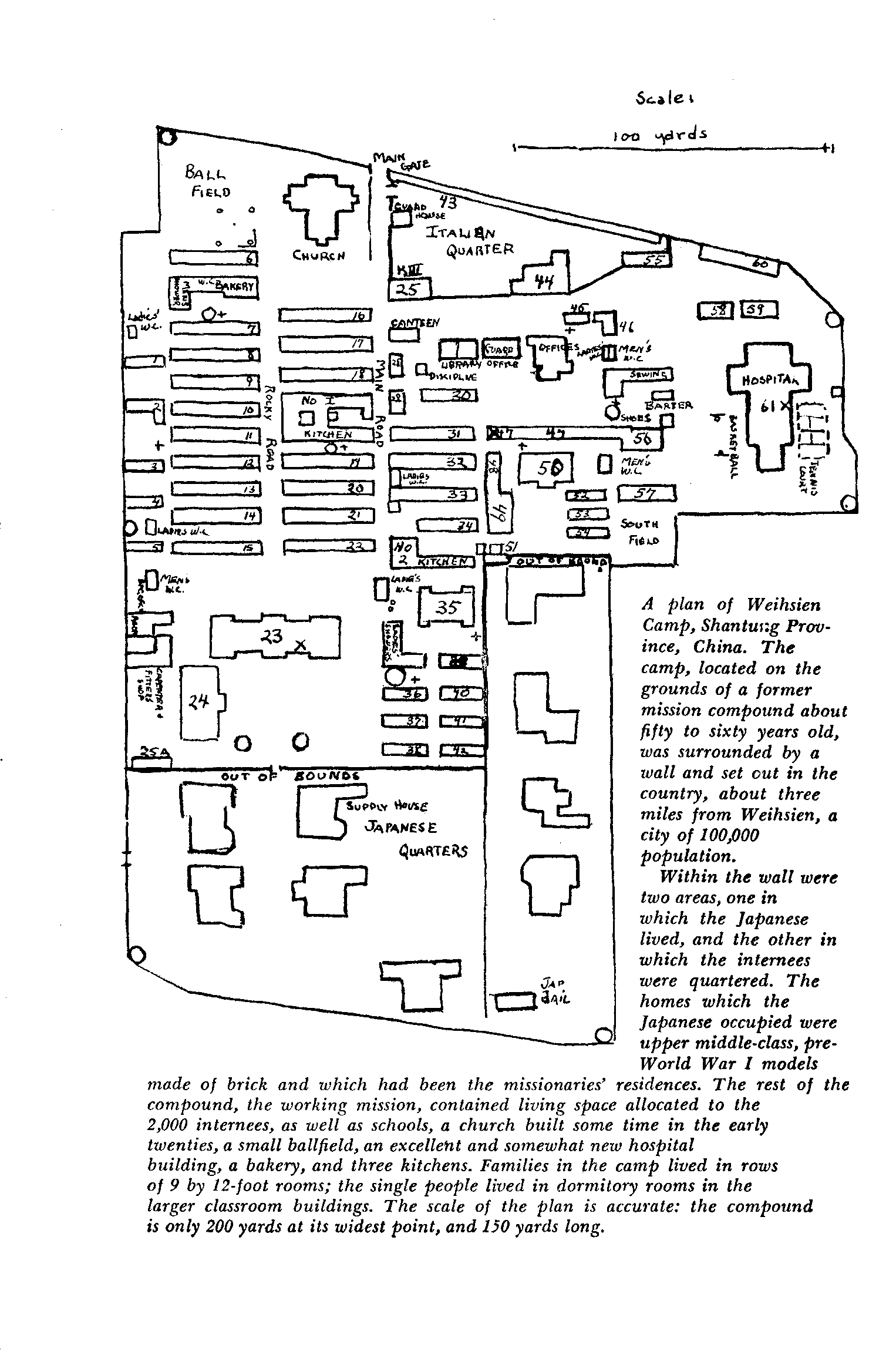

In stilted English sentences, the official letter announced that “for your safety and comfort” all enemy nationals would be sent by train to a “Civilian Internment Center” near Weihsien. This was a city in Shantung Province, two hundred miles to the south. The letter went on to declare that “there every comfort of Western culture will be yours.” For our own well-being we could send ahead a bed or cot and one trunk apiece. We were to bring our eating utensils with us. Beyond these items we were allowed only what we could carry by hand.

Meanwhile, the letter concluded, we were all to make preparations for this “rare opportunity” which the Japanese government was providing us.

How do you prepare for an internment camp? No one in the British or American communities knew/nor did anyone know exactly where we were going or what life would be like when we got there. Further rumors told us that the camp would be in an old Presbyterian mission compound, but beyond that we had no information. I pictured a life of monotony spent in a prison cell, and so rounded up copies of Aristotle, Spinoza, and Kant.

Another man, who took seriously the travel-brochure promises of the letter, lugged his golf clubs along. We were both wrong. Wiser heads in the community advised us all to bring blankets, towels, and basic camping and household equipment. They did say to be sure to pack some books, and if possible, musical instruments in our trunks. We were advised also to take our share of necessary medicines.

Committees made up of the few doctors and nurses among us were formed to see that the latter items were bought and distributed so that each of us would bring some medicines with us. Everyone tacitly agreed that since the trunks might not arrive for weeks at this remote spot, we had better carry with us as much in the way of extra warm clothing and woolens as we could.

On March 25, we Americans met in the former United States Embassy compound. On the great lawn surrounded by the empty and mindless buildings of officialdom long since fled, a motley crowd had gathered with all their varied equipment. There must have been about four hundred or so, males and females of all shapes and sizes, from every segment of society, ranging in age from six months to eighty-five years. The only thing we all seemed to have in common—besides our overloads of possessions—was a queer combination of excitement and apprehension. Were we bound for a camping vacation or the torturer’s rack? Because of the uncertainty, our emotions see-sawed, voices were loud and tempers short.

The group of teachers from Yenching University, of which I was a part, were, of course, familiar to me. Yenching was a privately owned Anglo-American university near Peking, one of ten “Christian Colleges” in China, with Chinese students and about one-third Western faculty. In our group were older professors, some young instructors in their twenties like myself, graduate students of Chinese like Stanley Morris, as well as numerous women professors. I also recognized the doctors from the Peking Union Medical College, the missionary families from the leading Protestant Boards, and some of the businessmen. The latter had been helping to provide leadership for the Americans in Peking since the beginning of hostilities a year and a half before, when we found ourselves captives of the Japanese and confined within the city walls of Peking.

But most of this varied crowd was new to me. There, a few feet away, for example, stood Karl Bauer, tall, straight, strong and sour, an ex-marine and ex-pro baseball player. Karl was never known to smile; for him everything that happened was an irritant, and everyone hostile. As we came later to know, he was capable of generating with less reason, more unhappiness in himself and others than anyone I have encountered before or since. Standing near him was a wan, paper-thin ghost of a man, with dirty, torn clothes, scraggly beard and sea-green complexion. His name proved to be Briggs, and he was the captive of a dope addiction that was slowly eating away what flesh remained his own.

By way of contrast, near the steps of the deserted Embassy office building was a knot of what were obviously wealthy older women. All wore furs and elegant hats. A few, I was told, were wealthy widows who had been living in retirement in Peking many years, and some were world travelers who happened to be caught and held in North China by the suddenness of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Further away, by the long-deserted American Ambassador’s residence, were what seemed to be hundreds of Roman Catholic priests, monks, and nuns. They were missionaries, who had been seized in Mongolia, and brought here from their monasteries to go to camp with us. The panoply of civilian life in all its wonderful and amazing variety seemed to be represented here.

We stood waiting for orders. Each child clutched his teddy bear; single persons and families alike stood surrounded by the miscellaneous heaps of bags, duffels, coats, potties, and camp chairs—all this assorted gear, in spite of the stern Japanese warning that we must bring only what we could carry.

That warning had been issued in earnest. At noon sharp, a Japanese officer shouted through a megaphone that everyone must pick up his own belongings and carry them by hand to the railway station. A horrified gasp swept through the crowd. Every elderly person, every father of a family, every single woman thought of the station a mile away and then looked in near panic at the mountain of his own stuff at his feet. In the group were a goodly number of men alone—many of whom had sent their families home the year before—but since each of them had already brought as much as he could manage, they could not carry it all. Even the old and the very young had somehow to drag their things. Everything was a necessity. How could anyone bear to leave anything behind when he was bound to a strange life of indeterminate duration in a faraway concentration camp?

The Japanese officer again barked out his order to march.

There was nothing to do but to pick up the things and start moving. Every man, with the exception of those over seventy, carried the bags of at least two other persons. So, by a process of dragging and resting, of dragging some more and resting again, the march began. Slowly we crawled out of the Embassy compound and onto the main streets of Peking.

Here we found that the Japanese had lined up most of the city’s Chinese population along the street to view our humiliation. The Chinese had been our allies against the Japanese; they had done much for us since the beginning of the war. And yet, because they themselves had been ruled so long by the West, they must have had mixed emotions as they impassively watched these four hundred white Westerners stagger weakly through their streets. We knew the Japanese intended that these marches, which took place throughout the cities and ports of China, be the symbol of the final destruction of Western prestige in the Orient. For that reason, we tried our best to walk erect and to present a dignified mien. But that is a hard enough job for a young man carrying four of five heavy bags. It was hopeless for the elderly. So on that sad mile we provided precisely the ridiculous spectacle that the Japanese hoped for. From this late vantage point, it is plain that the Japanese had guessed correctly: the era of Western dominance in Asia ended with that burdened crawl to the station.

A full hour had passed before that march was finally over. It was a great relief to hear that it had caused no more than one fatal heart attack and two fainting spells.

At the station we were told that a train would be ready to take us to Weihsien in another hour or so. Meanwhile we were ordered not to move from the platform or to make contact with the Chinese. This latter proscription was far from welcome since it meant that no more food and no more liquid could be purchased from the hawkers, who now stared at us wistfully from another platform with a look of disappointment matched only by our own. We would have to make do on the long trip to Weihsien with the little that each of us had brought along. So we all sat down on our belongings and waited. We sipped from our canteens and nibbled on our sandwiches.

The train ride itself was no improvement. We were jammed into the straight, wooden seats of Chinese third-class carriages, some of us standing, some sitting on luggage. In this comfortless state, we lurched and bounced for twenty-four hours two hundred miles into the south. For the old people, exhausted from the march, for infants and young children, that night on the hard boards of the jolting smelly train must have been a nightmare. Every rattle of the loose windows, or screech of the old-fashioned whistle was accompanied by the cries of those miserable youngsters suffering from hunger, from thirst, and from just plain fright.

No one could sleep. We talked endlessly about what might lie ahead. Would we be in cells? If so, what would we do there? Would they work younger men to death, as we had heard? Would there be enough food? Again our thoughts were a strange brew of excitement, apprehension, and curiosity. What would camp be like?

We were well into the long night when the sound of singing drifted in from the coach behind us. It came softly at first and then grew loud enough to drown out the cries of the children around us. We looked back to see a car filled with pipe smoke through which we could discern dim, monastic, bearded figures. These monks, cheerful and certainly untroubled by discomfort, were loudly singing Dutch and Belgian student drinking songs. After a moment’s surprise and delight at this totally unexpected aura of easy good humor, some of us moved back to their car, joined in lustily, and sang ourselves hoarse as the train lurched over the dark plains and into the darker unknown ahead.

Our food and water ran out early in the night; no one had any sleep to boast of, so it was a dirty, stiff, tired, and hungry crew that arrived at the Weihsien city station in the middle of the next afternoon. On hand to greet us was a British businessman from Tientsin who had been sent to camp four days before when the first Tientsin group arrived. We were pleased to hear that army trucks would come shortly to take us to the camp, some three miles outside the city walls. But his second statement gave us all a jolt. No Chinese would be allowed in camp. No Chinese? Who, then, would be the No. 1 boys in this new world? Who would cook the food and feed the fires necessary for life and warmth? And with that thought, I could feel the years of being waited on and served, both at home and at college, going down the drain. I could feel the familiar comforts of being provided with heat, food, warm water, and clean clothes peeling off—and a quite new life beginning.

Soon, however, the trucks arrived and we clambered into them with our baggage. After a forty-minute ride through the cobbled streets of the city, through the massive gates in the city walls and out across three miles of countryside, we arrived at the compound. Curious as to what our future would be inside those walls, we climbed stiffly out of the trucks and looked around.

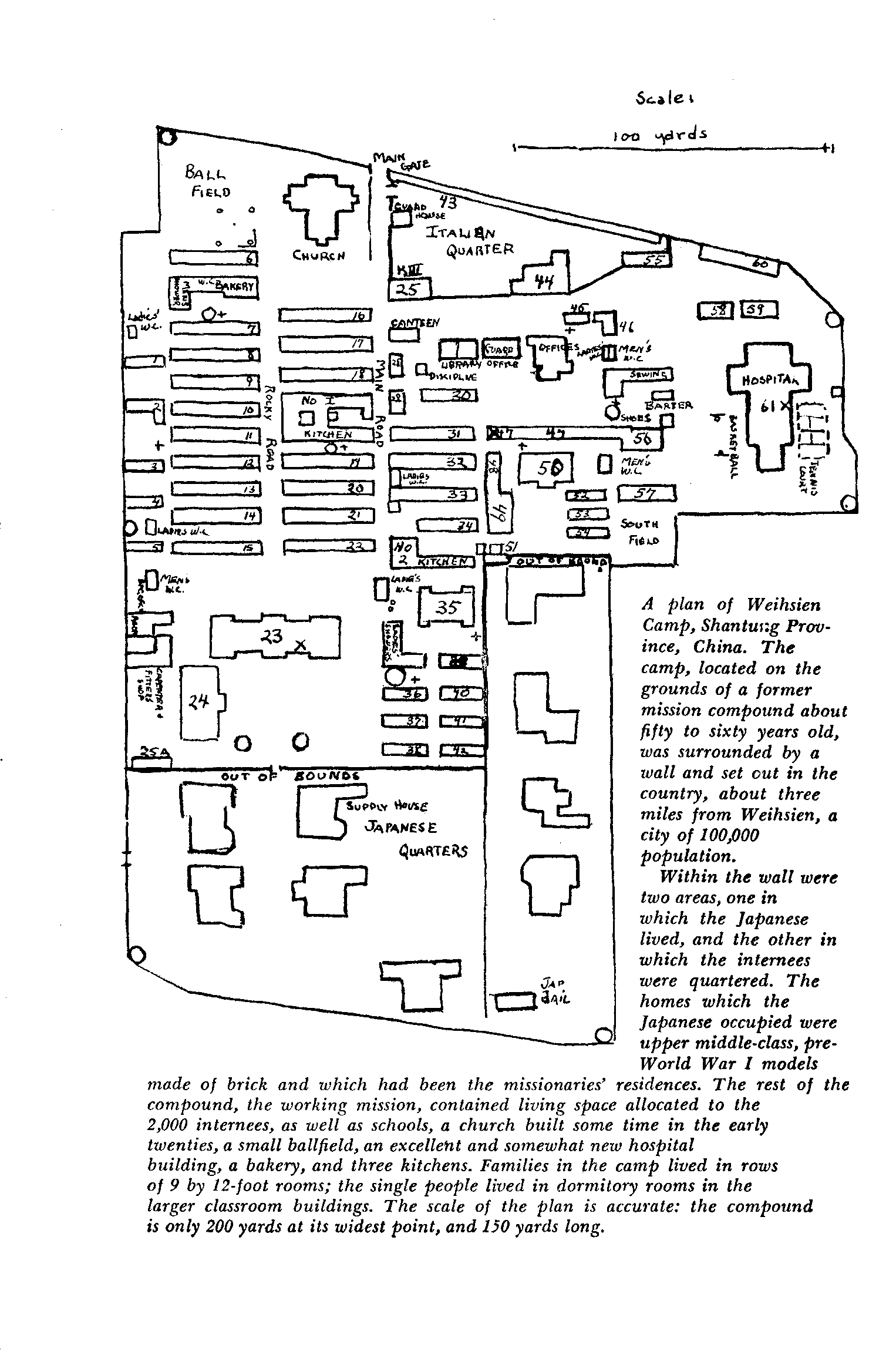

The compound looked like any other foreign mission station in China, dull gray and institutional. It seemed roughly the size of most of them—about one large city block. There were the familiar six-foot walls that surround everything in China; there were the roofs of Western-style buildings appearing above the walls; there was the welcome sight of a few trees here and there inside the compound; and, of course, the familiar great front gates. Stretching endlessly on either side was the bare, flat, dusty Shantung farmland over which we had just come. We turned to take a last glance at that landscape. The guard on our truck barked at us, and we started up the slope toward the gate.

The first sight that greeted us was a great crowd of dirty, unkempt, refugee like people, standing inside the gate and coldly staring at us with resentful curiosity. Their clothes looked damp and rumpled, covered with grime and dust—much as men look who have just come off a shift on a road gang.

“My God,” I thought, as I stared back at them with disgust, “they look like real freight-yard bums. Why haven’t they cleaned themselves up a little bit?”

A feeling of utter dreariness came over me as I looked at them. Would we, in time, become as drab and disheveled as this crowd? Was this dull dirtiness to be the character of our life here?

Who were these people? I wondered. With some distaste, we learned that they were earlier arrivals. Some came from Tsingtao, a nearby port city, and some from Tientsin. It had never really occurred to me that there would be anyone in camp besides our small Peking group.

At this sudden confrontation with total strangers, I felt excitement as well as antipathy. Paradoxically, the camp might offer a wider, livelier universe for a young man than our small world of academicians, business people, and missionaries in Peking. Immediately I found myself “checking the crowd,” searching eagerly for a pretty face or a rounded figure—and, sure enough, even among that scruffy- looking lot there were three or four.

Still looking about us curiously, we were led from the gate past some rows of small rooms, past the Edwardian-style church, out onto a small softball field in one corner of the compound. Here we were to be lined up and counted. For the first time I noticed the guard towers at each corner or bend of the walls. I felt a slight chill as I noticed the slots for machine guns, and the electrified barbed wire that ran along the tops of the walls.

Then a considerably greater chill swept me as I saw that the machine guns were pointing our way.

And a sense both of complete change and of utter reality came over me. Suddenly I felt what it was like to be inside something, and stuck there; and what is more, inside an internment camp from which one could not get out for any reason whatsoever, a camp run under the iron discipline of an enemy army.

With this awareness I could feel my world shrink: the country-side beyond the walls receded and became unreal—like the pictured scenery of a stage set. The reality in which I had now to exist seemed barely large enough to stand on, let alone large enough to be alive in. With a feeling of genuine despair I thought, “How can anyone live enclosed in this tiny area for any length of time? Will I not go wild with cramp, with boredom? What can there be to do in this dreary place?”

I moved dejectedly toward a doctor I knew, who was talking to the “leader” of the Peking Americans, William Montague, of the British American Tobacco Company. Seated on a small mound on the edge of the diamond, Montague was the cheerful center of animated chatter and amused laughter. This able man, undismayed by any misfortune, seemed more like a happy old grad at a homecoming game in his soft camel’s hair topcoat, than the responsible head of an internment-camp community. Apparently the Japanese had told him to pick one man to be in general charge of our group (Montague, needless to say, had regarded himself as already appointed to this post!), one other person to handle housing, and another to organize our food and cooking. This group of lively participants was suggesting names of men suitable for these our first political positions. I do not know what prompted me, a young teacher of English and philosophy barely twenty-four, to enter this world of affairs. Anyway, I blurted out the name of Dr. Arnold Baldwin for the housing job. I was aware that he had been head of an American Quarters Committee formed in Peking after the start of war to help homeless Americans. Montague looked up at me at this—he hardly knew me—and said quickly and coldly: “Oh, no, Baldwin has much more important work than that to do here. There will be more sickness in this mess than any number of doctors can take care of!”

Knowing he was absolutely right in his observation, I felt ashamed for having put in my two cents. I started to turn away, when, to my amazement I heard Baldwin say, “All right, I’ll accept that—but how about young Gilkey here for housing?”

Montague looked at me again, narrowed his eyes, and said, “All right, Gilkey, you help me with this housing stuff, and I’ll take over the general charge of the group—Dr. Foster can handle medicine, and we’ll find someone for cooking when we’ve had a look at the kitchen setup.”

I swallowed hard and said nothing. I had no knowledge of housing and had hardly any administrative experience. But still, I thought, who did know how to house people in an internment camp? Surely working with the effervescent Montague would be more diverting than staring dolefully at my shoes from the side of a bed! So I said I would take a crack at the housing job, and went back to join my friends.

Just then we were lined up in rows to be counted and harangued. We found ourselves listening to a set speech on the rules of camp life, and on our good fortune at being there. At the end we had to swear to cooperate with our overlords in anything that they might ask of us. It sounded grim enough. The March wind was becoming freezing cold. But something new had entered into this drab scene. I remembered my glimpse of two or three shapely girls in the motley crowd at the edge of the ball field. Also as we parted, Montague had said that tomorrow night there was to be a meeting of “leaders,” and I could help him by going along with him and taking notes.

When this initial roll call was finished, one of the earlier arrivals in camp, another British businessman from Tientsin, gathered the men of our Peking group together. He was natty in a plaid wool shirt, bow tie, gray tweed coat and checkered hunting cap, but all of this elegant ensemble was slightly soiled from a solid week’s wear. He led us over to our temporary quarters, while others conducted the families and the single women to theirs.

“Ours” turned out to be the basement of one of the two school buildings. We were ushered into a large room without furniture, its cement floor damp and dirty. There were naked bulbs hanging from the ceiling, and great wet splotches showing through the broken plaster on the walls. We were told that in the corridor were rush mats for us to sleep on, and that we ought to hang onto them since the beds we’d sent weren’t likely to arrive for several weeks. Meanwhile, we were to wash up and in half an hour- get our first meal at the kitchen run by earlier arrivals from Tsingtao. By the following day we were to get our own Peking kitchen in operation, for it would have to feed the next batch of internees from Tientsin who were due in a couple of days.

“Ours” turned out to be the basement of one of the two school buildings. We were ushered into a large room without furniture, its cement floor damp and dirty. There were naked bulbs hanging from the ceiling, and great wet splotches showing through the broken plaster on the walls. We were told that in the corridor were rush mats for us to sleep on, and that we ought to hang onto them since the beds we’d sent weren’t likely to arrive for several weeks. Meanwhile, we were to wash up and in half an hour- get our first meal at the kitchen run by earlier arrivals from Tsingtao. By the following day we were to get our own Peking kitchen in operation, for it would have to feed the next batch of internees from Tientsin who were due in a couple of days.

We deposited our gear on the cold cement floor, and found mats, for our beds. Then some of us went out to look for the toilet and washroom. We were told they were about a hundred and fifty yards away: “Go down the left-hand street of the camp, and turn left at the water pump.” So we set off, curiously peering on every side to see our new world.

After an open space in front of our building, we came to the many rows of small rooms that covered the camp except where the ballfield, the church, the hospital, and the school buildings were. Walking past these rows, we could see each family trying to get settled in its little room in somewhat the same disordered and cheerless way that we had done in ours. In contrast to the unhappy mutterings of miscellaneous bachelors, these rooms echoed to the distressed cries of babies and small children.

Then we came to a large hand pump under a small water tower. There we saw a husky, grinning British engineer, stripped to the waist even though the dusk was cold, furiously pumping water into the tower. As I watched him making his long, steady strokes, I suddenly realized what his presence at that pump meant. We ourselves would have to do all the work in this camp; our muscles and hands would have to lift water from wells, carry supplies in from the gates. We would have to cook the food and stoke the fires—here were neither servants nor machinery, no running water, no central heating. Before we passed on into the men’s room, the British pumper, whose back was rising and falling rhythmically, fixed us as best he could in that situation with a cheerful and yet hostile eye, and reminded us with as much authority as his gasps would allow, “Every chap will be taking his full share of work here, chaps, you know!”

As we entered the door of the men’s room, the stench that assailed our Western nostrils almost drove us back into the fresh March air.

To our surprise, we found brand-new fixtures inside: Oriental-style toilets with porcelain bowls sunk in the floor over which we uncomfortably had to squat. Above them on the wall hung porcelain flushing boxes with long, metal pull-chains, but— the pipes from the water tower outside led only into the men’s showers; not one was connected with the toilets. Those fancy pipes above us led nowhere. The toilet bowls were already filled to overflowing—with no servants, no plumbers, and very little running water anywhere in camp, it was hard to see how they would ever be unstopped. We stayed there just long enough to do our small business—all the while grateful we had not eaten the last thirty-four hours—and to wash our hands and faces in the ice-cold water that dribbled out of the faucets.

Back outside, we strolled around for our first real look at the compound. I was again struck by how small it was—about one hundred and fifty by two hundred yards. Even more striking was its wrecked condition. Before the war, it had housed a well- equipped American Presbyterian mission station, complete with a middle, or high, school of four or five large buildings, a hospital, a church, three kitchens, bakery ovens, and seemingly endless small rooms for resident students. We were told that, years before, Henry Luce had been born there. Although the buildings themselves had not been damaged, everything in them was a shambles, having been wrecked by heaven knows how many garrisons of Japanese and Chinese soldiers. The contents of the various buildings were strewn up and down the compound, cluttering every street and open space; metal of all sorts, radiators, old beds, bits of pipe and whatnot, and among them broken desks, benches, and chairs that had been in the classrooms and offices. Since our “dorm” was the basement of what had been the science building, on the way home we sifted through the remains of a chemistry lab. Two days later we carried our loot to the hospital to help them to get in operation.

The one redeeming feature of this dismal spectacle was that it provided invaluable articles for the kind of life we had now obviously to live. Old desks and benches could become wash-stands and tables in our bare quarters. Broken chairs could give us something to sit on besides the wet floors. Clearly the same thought had occurred to others; as we walked home, we saw in the dim light, dingy figures groping among the rubble and carting off “choice” bits and pieces. We made up our minds to get started on our own “scrounging” operations first thing in the morning before all this treasure was gone.

Soon after we got back to our room, we were led over to another part of the compound for supper. I saw stretching before me for some seventy yards a line of quiet, grim people standing patiently with bowls and spoons in their hands. Genuinely baffled, I asked our guide—a pleasant man from Tsingtao, with all the comfortable authority of one now quite acclimated to camp life—what on earth they were doing there.

“Oh, queuing up for supper, of course, old boy,” said the Englishman cheerfully. “You’ll get yours in about forty minutes, actually, if you join the queue now.”

Could human patience bear such a long wait three times a day for meals? However, I joined the line, and three-quarters of an hour later, we reached the table where thin soup was being ladled out along with bread. That was supper. Fortunately, there were “seconds” on bread, because we were very hungry after our long train trip without food; I ate five to ten slices to help supplement the tasteless gruel.

Our meal finished, we lined up again to have our bowls and spoons washed by women from Tsingtao. The patterns of chores in the new situation were beginning to come clear. As I went out past the steam-filled kitchen with its great Chinese cauldrons, I saw three men from our Peking group being shown how to use the cooking equipment by the men from Tsingtao, turned into “experts” by their three days of practice. Despite that tasteless meal, I felt content; I was no end proud of my job in housing and looked forward to finding out more about this strange camp and how it worked.

When we walked back to our quarters, it was already getting very cold. The climate in North China is not unlike that of Chicago or Kansas City. Thus in March ice can still form at night, and unless one has dry clothes and some measure of heating, one can freeze. Needless to say, having neither, we felt chilled to the bone as we stamped about in our bare basement room. There was nothing to do but try to go to sleep. People must have some place to sit if there is to be a bull session of any sort! And so, still in our clothes, we lay down on our mats. Since each of us had only the things he had been able to bring with him, overcoats became extra blankets and sweaters were pillows. For long I lay there, trying unsuccessfully to find a soft spot in my cement mattress, but sheer fatigue finally overcome even that discomfort, and I fell asleep.

We awoke the next day to a cold drenching rain that had turned the compound into one great mud swamp. In the midst of this downpour, we new arrivals were once more called to the ballfield. Here we were again counted, sworn in, told to be good and, this time, ordered to surrender all our cash. Having been warned by the Tsingtao group that compliance with this order would be a completely unnecessary virtue, we kept back most of our cash, hidden in our shoes and our underwear.

We awoke the next day to a cold drenching rain that had turned the compound into one great mud swamp. In the midst of this downpour, we new arrivals were once more called to the ballfield. Here we were again counted, sworn in, told to be good and, this time, ordered to surrender all our cash. Having been warned by the Tsingtao group that compliance with this order would be a completely unnecessary virtue, we kept back most of our cash, hidden in our shoes and our underwear.

After this, slopping in puddles, wet to the bone, angry but intensely curious, we were guided by a guard to our new “permanent” quarters. These were better by far than the wet basement room of the previous night, but still hardly ideal. In three small 9-by-12-foot rooms, dirty beyond description, we eleven bachelors were crammed into a space comfortable for only four or five people. There were the same bare walls and floors, only our suitcases to sit on and our straw mats to lie on—and no sign of any heating. It was messy, bleak, cold, and wet. Until our beds arrived two weeks later, every place in camp was like that.

The wonder is that flu or pneumonia did not decimate this vulnerable population. Fortunately, I was young and had warm clothes. It certainly never occurred to us to take anything off when we slept on the floor. Thus at the end of two or three days we looked just as bedraggled and unkempt as did the internees we had held in scorn upon our entry into camp.

This existence was of the greatest conceivable contrast to all that had gone before in my life, and the same was true for almost everyone there.

Brought up in the comfort of an upper-middle-class professional home at a large Midwestern American university, where my father had been Dean of the Chapel, I had been waited on by maids at home and in the opulence of prewar Harvard College from which I graduated with an A.B. in 1940 just before coming to China to teach English at Yenching. In twenty-four years I had known little else than steam heat, running hot and cold water, a toilet in the next room, good food, clean clothing, plenty of space, and a quiet, academic existence. Only occasionally, when cruising or camping, had these comforts of civilization been absent. These periods, however, were short, voluntary, and such fun that they made no lasting imprint. Life to me, as to most of the camp, was civilization. Existence on any other terms was almost inconceivable. But at Weihsien all the vast interconnected services of civilization had vanished, and with them had gone every one of our creature comforts.

If this great crowd of people were to survive, much less to live a passable life, a civilization of some sort would have to be created from scratch. Gradually the nature of the problem facing our community dawned on me. As it did so, everything took on an intensity and excitement I had not known before. Thus for a healthy young man those first weeks of camp were an absorbing experience—physically no worse than army life in the field and yet much more interesting. However, for men and women in their late sixties and seventies in the single dorms, for the sick or the incapacitated, and above all, for the babies and children and their troubled mothers, those first weeks, with no heat and no beds, were a nightmare which I am sure none of them can recall to this day without shuddering.

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/p_Gilkey.htm

#