- by Meredith & Christine Helsby

Chapter 5

[excerpts] ...WEIHSIEN

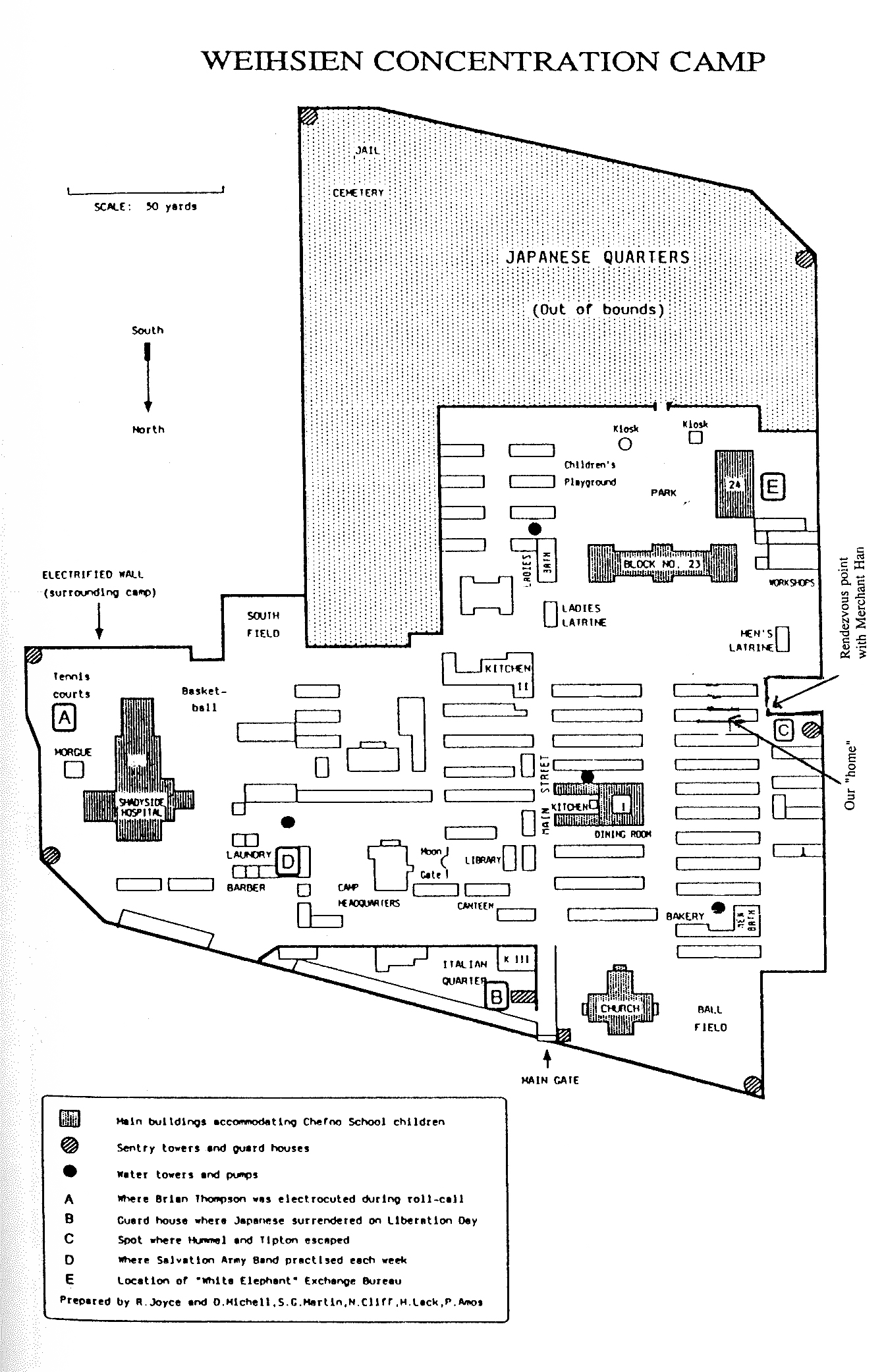

With the dawn of our first day in Weihsien Camp came the opportunity to explore our surroundings.

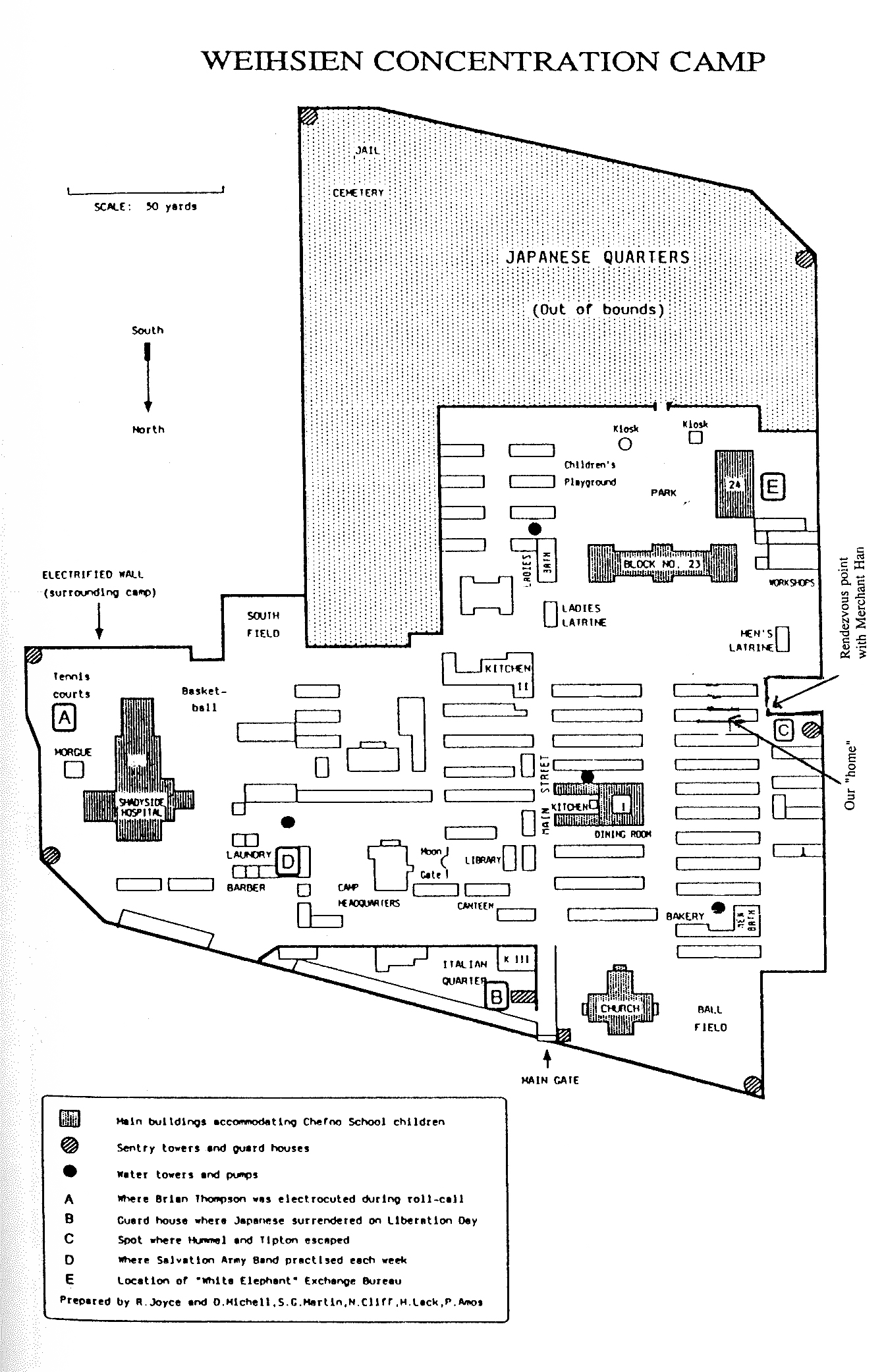

Weihsien had seen happier times. In its prime, during the early years of the century, it had been a model missionary compound of the American Presbyterian Church.

Within the walls of the six-acre enclosure were a Bible school, hospital, bakery, long rows of single-story dormitories, and western-style homes for American missionary doctors and teachers. In fact, two notable personalities, novelist Pearl Buck and Henry Luce, founder of Time and Life magazines, had both been born there.

Weihsien had seen happier times. In its prime, during the early years of the century, it had been a model missionary compound of the American Presbyterian Church.

Within the walls of the six-acre enclosure were a Bible school, hospital, bakery, long rows of single-story dormitories, and western-style homes for American missionary doctors and teachers. In fact, two notable personalities, novelist Pearl Buck and Henry Luce, founder of Time and Life magazines, had both been born there.

Leading from the high wooden gates up the slope through the center of the one-time campus was a black cinder road which we came to call “Main Street.” On either side was an assortment of buildings. Behind them rose what had at one time been splendid edifices of Edwardian architecture, housing the administration building and the hospital.

For more than a year both Chinese and Japanese troops had been quartered on this compound, and although the buildings had not been damaged their interiors were in shambles with fixtures ripped out and furnishings ruined. Their contents now were scattered about yards and doorways in unsightly piles of debris. Gratefully, a good deal of this material could now be salvaged, refashioned and put to good use. We all learned a new word, “scrounge,” which meant picking up any piece of anything we thought would make our homes more livable.

In his well-known book Shantung Compound one of the internees, Langdon Gilkey, gives a graphic description of our community:

- We were, in the words of the British, a “ruddy” mixed bag. We were almost equally divided in numbers between men and women. We had roughly 400 who were 60 years of age and another 400 under 15. Our oldest citizen was in his mid-90s, our youngest was a baby who had just been born in the camp hospital.

We were equally diverse in our national and racial origins. At the start of camp our population comprised about 800 Britains, 600 Americans, 250 Hollanders, 250 Belgians (the major portion of the last two groups were Roman Catholic clerics of various sorts).---

‘These are approximate numbers. Scandinavians should also have been included. By April 1, 1943, our camp population numbered 1,751.---

--- We were later joined by about 100 Italians from the Shanghai area, who were placed in a separate section. Interspersed throughout were eight Belgian and two Dutch families, four Parsee families, two Cuban families, part of a touring jai-alai team, a Negro and Hawaiian jazz band, a few Palestinian Jews, an Indian translator and interpreter and about 60 White Russian women and their children... .

--- Called White Russians because they were politically aligned with the Mensheviks (whites) who were defeated by the Bolsheviks (reds) in the power struggle following the revolution of 1919.---

The most obvious diversity lay in the differences in the social status which each of us had enjoyed in the outside world. As we could see from the first moment, our group ranged up and down the entire social ladder.

Our members included some from the well-to-do leaders of Asia’s colonial business world and the genteel products of English “public school” life. More were from the Anglo-Saxon middle-class (represented by small businessmen, customs officials, engineers, exporters, lawyers, doctors and shop-keepers), and not a few from among the dopers, barflies and raffish characters of the port cities. Mingling with the secular hoi polloi were some 400 Protestant missionaries. They embraced almost all denominations, theologies and ways of life.

Also, for the first six months, there were 400 Roman Catholic priests, monks and nuns. . . . When the last group arrived in camp, we totaled nearly 1800.

The first great crisis faced by this vast hoard of people thrust so unceremoniously into the ill-prepared compound was occasioned by the basic demands for toilet facilities. Since our captors were ensconced in the western missionary homes there remained four simple latrines containing no more than five or six toilets apiece to service our entire community. These toilets were of the simplest Chinese design, mere holes in the floor bereft of flushing mechanisms and designed to be emptied regularly by Chinese coolies with “honey buckets”

From dawn to dusk lines outside the latrines were interminable, and before long contents were overflowing, creating the most repulsive conditions imaginable. This was a special trial for women, due not only to their delicate sensibilities but to the fact that they had only one latrine to the men’s three. This, we learned, was due to misinformation the Japanese had received concerning the ratio of the sexes of their captives.

This situation was somewhat alleviated when a delegation of volunteers, among them intrepid Catholic nuns, tied cloths over their faces and waded into the loathsome mass of excrement to clean it up. In time, a crew of engineers devised a system for hand-flushing the toilets after each use.

The first day after our arrival at the Weihsien Compound, we were summoned to the playing field to be identified and counted, an irritating ordeal that took several hours. The commandant read the rules. One strictly specified that we were to have no contact with the Chinese on the outside of the wall. This was a fore-taste of the innumerable roll calls, an immutable feature of camp life.

The bell tolled at 8:30 each morning and again at 6:30 p.m. (earlier in the winter). This was to summon the entire camp population to six designated areas.

Residents of our section assembled in the church yard in rows of 20, I.D. badges properly displayed on the left shoulder. This ritual required no less than 45 minutes, often much longer if somebody couldn’t be accounted for. Gratefully, while waiting to be counted, we were permitted to relax and visit with friends.

The stern-faced officers who moved at such a deliberate pace to peer at our badges and check our names in their registers soon became familiar figures to us. Fortunately the 70 guards assigned to the Weihsien camp were not members of the regular Japanese army but civilian diplomatic officers, who had served in various capacities in China, thus a cut above the typical soldiers who brutalized Allied prisoners in the infamous P.O.W. camps in Singapore and the Philippines.

For the most part, the guards’ treatment of us was marked by decorum and good discipline, and efforts were made to observe the articles of the Geneva Convention governing treatment of civilian prisoners of war. A few, like Mr. Kogi who had studied in a mission school, had come in contact with Christianity in Japan and went out of their way to treat us with consideration and courtesy.

Still when our captors, small of stature and looking almost like children beside a 6 foot 2 inch American or Englishman, felt intimidated they could respond with unfeigned arrogance or fly into a rage barking, ranting, gesticulating, slapping and kicking. When in dress uniform these diminutive men strutting back and forth, their long Samurai swords trailing in the dirt, looked so much like small boys at play it was hard to suppress a smile. Smiling or laughing in their presence, however, is something we early learned to avoid — as this was often taken as a sign of contempt, insolence or lack of respect, inviting angry reprisals and threats.

Among 70 men of any nationality one will, of course, discover tremendous diversity. And while some of these guards early identified themselves as friendly, others we soon learned to give a wide berth. A few acquired interesting nicknames.

The commandant, a heavy scowling man of surly disposition, was soon dubbed “King Kong.” Another officer, who looked like the Japanese counterpart of Sergeant Snorkle, took a perverse delight in squelching any activity which appeared suspiciously like fun. The sight of an internee sunbathing or a couple holding hands would elicit a growled “Pu Hsing Ti.” (You can’t do that!)

---’Wade-Giles Romanization was in wide use during World War II era.---

Soon he had earned the moniker Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti. Before long wherever this gentleman appeared, he was greeted by throngs of small children who followed, dancing up and down chorusing, “Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti, Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti.”

This was most disconcerting, of course. So much so that the man appealed to the commandant, and a short time later the following announcement appeared on the camp bulletin board: “Henceforth in the Weihsien Civilian Center, by special order of His Imperial Majesty, the emperor of Japan, Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti is not to be known as Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti but as Sergeant Yomiara.”

Life is full of surprises, and we soon learned it was a mistake to judge the Japanese by their appearance. One internee described a surprising encounter with a menacing-looking guard:

It was with great apprehension that we saw one afternoon at tea time one of the soldiers, loaded down with every kind of portable weapon, approach a building where, among others, an American family with a baby was housed. I was the only male present at the time.

Gingerly I opened the door at the guard’s brisk knock. He bowed and sucked air in sharply through his teeth. Then unloading his extensive armor, to my utter amazement he opened his great coat and pulled out a small bottle of milk.

“Please,” he said haltingly, “take for baby.” After we had recovered from our surprise sufficiently to invite him to come in, we asked whether there was anything we could do for him in return.

“May I hear classical records?” he asked. Again we gasped and said, “Who are you?” He answered, “I, second flutist in Tokyo Symphony Orchestra. Miss good music!”

Weihsien camp was, in effect, a hastily assembled city of 1800 people of 17 nationalities wedged into the confines of a six-acre compound. All of the organizations and services that develop in a normal community over decades we were now forced to construct almost overnight. In this enterprise, our Japanese overlords demonstrated the commendable gifts of efficiency and administration that have made them the world leaders in commerce and industry.

...

[further reading ] ...

(copy/paste into your internet browser !)

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/GordonHelsby/Helsby(WEB).pdf

#