- by Ron Bridge

Chapter 6

[exerpts] ...Settling in to Strange Surroundings

In spite of the rock-hard floor I slept well that first night in camp.

On reflection it was not surprising, as there had been two days of travelling, a night when I had not seen a bed followed by a day without food. I woke up to hear someone knocking at the door.

`Who is that?’ Mum called out nervously. `Wait a moment. I’m coming.’

`Who is that?’ Mum called out nervously. `Wait a moment. I’m coming.’

She got to her feet, and her movement woke Roger who had been lying on bundled-up clothes between Mum and Dad since daylight.

Then he promptly started wailing.

`It is only me Margot’ called out the familiar voice of my grandmother. `I have just come down to see how you are and how you managed on the journey.’

It was wonderful to see her small figure outside, well wrapped in her everyday grey woollen coat. Granny was not much taller than I, just under 5 foot; she was rather rounder, but at that moment she was a comfortingly familiar figure. Her face was serene as usual and her grey hair had been drawn into a neat bun at the nape of her neck. She was wearing her usual pince-nez glasses. Mum did not look much like her, being much slimmer and 6 inches taller. Granny kissed her daughter, gave me a hug and picked up Roger who immediately stopped bawling.

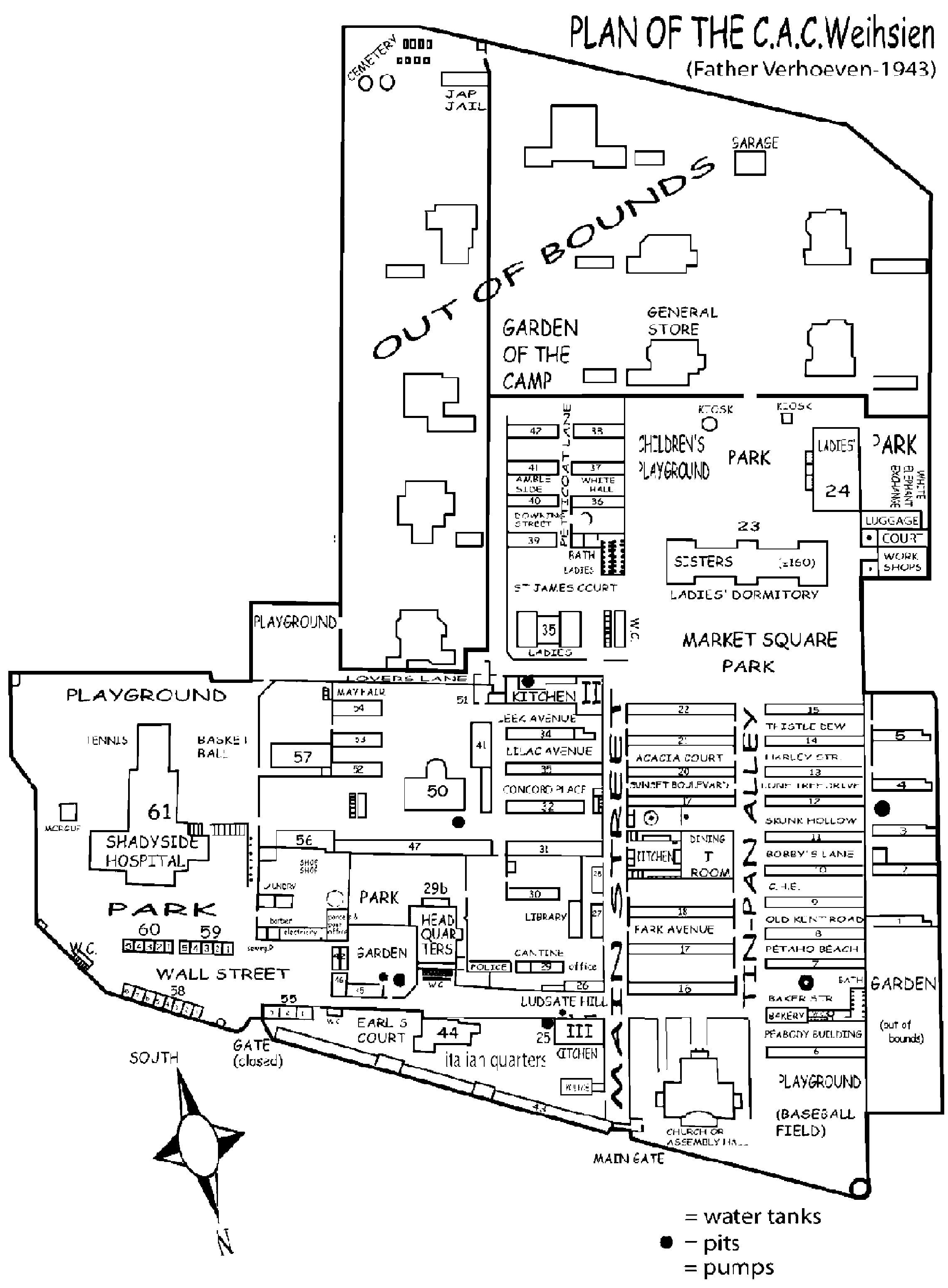

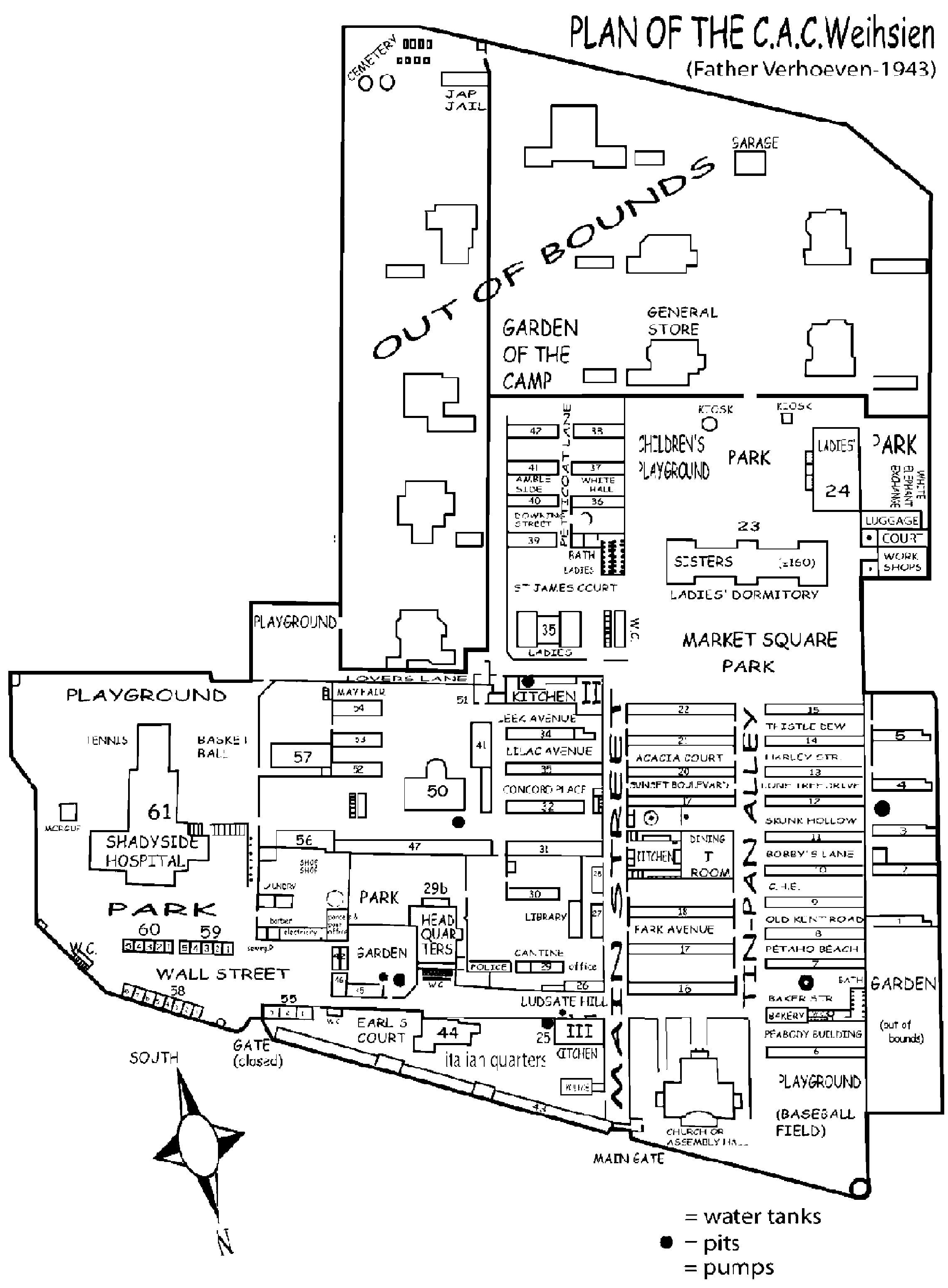

`Where is Leo?’ Granny asked. `Has he gone off to get your breakfast? I was going to take you down to the kitchen. We have to use Kitchen No. 1 as we are over in Block 13 but you are in Block 42 and will have to use Kitchen No. 2. Both kitchens have dining rooms attached.’

`Last night Leo brought us our supper here, and I think he will do the same today.’ Mum added quickly, `I don’t really want to take Roger to a public dining room. We haven’t got a high chair for him and he will just be a nuisance if he cries all the time.’

I had only just realised the significance of Dad not being in the little hut. But if he was off getting food that was all right. I was starving hungry again and I slipped outside to watch for his coming back.

The night before, I had not really taken things in regarding my surroundings. It had been at least half dark, and I was too tired and upset to care where we were, so long as I could get food and somewhere warm to sleep. Now, as I stood outside, I realised we were in a little courtyard, with six rooms in our block and six more in the next. The path separating the two blocks was in the middle and led to the rest of the camp.

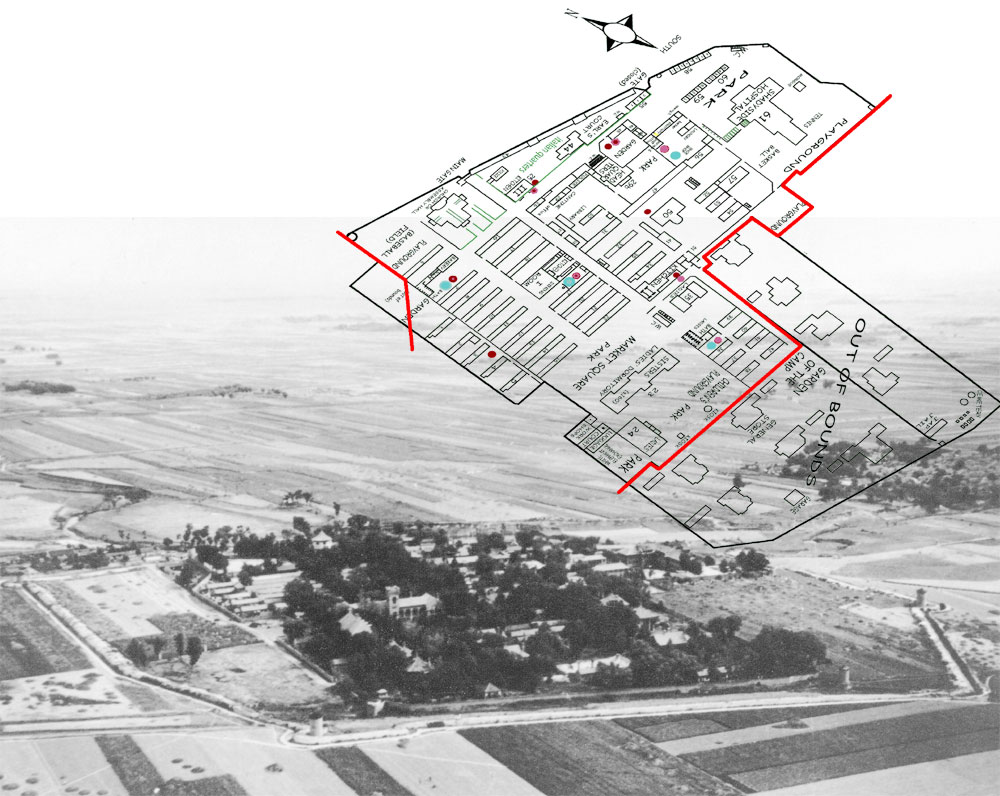

Granny pointed out that the wall on the left and in front of us divided us from where the Japanese guards lived, in the old missionary houses, and that that area was prohibited to all internees. She went on to say that the huts that we were living in had been the student quarters when Weihsien was an American Presbyterian Mission School. Founded in 1883, Weihsien played a leading role in establishing primary and secondary schools for girls throughout its mission field. The missionaries had begun with a conservative agenda of creating good Christian households at the time, and Weihsien, as it now was, had originally been just a single building; it grew to encompass a compound containing a high school, a large three-storey hospital, called Shadyside, the Arts College of the Shandong Christian University, a Bible School, and residences for the missionaries and teachers. The 1911 Revolution had boosted its status, followed by subsequent injections of American money. In addition to its institutions, the mission established schools and dispensaries throughout its catchment area, covering some 400 square miles around the station in Weihsien. These schools not only trained female students to become professional teachers and nurses, but also enlightened them in the local cultural sphere. Sadly, the invasion of the Japanese in 1937-8 meant that all the laboratories and operating theatres had been looted; indeed, the hospital had had all its plumbing ripped out.

Along the path I could see another three sets of buildings like ours, and then more structures beyond. More important I could see Dad walking towards us, bringing breakfast in a Chinese-type food carrier, which Mum had thoughtfully packed in case there was going to be communal catering. We had only bread, weak tea and a little milk for Roger, but it tasted very good and after this I was ready to check out the neighbourhood. Mum wanted to unpack and sort out our small home, which I considered pointless until our beds arrived.

Along the path I could see another three sets of buildings like ours, and then more structures beyond. More important I could see Dad walking towards us, bringing breakfast in a Chinese-type food carrier, which Mum had thoughtfully packed in case there was going to be communal catering. We had only bread, weak tea and a little milk for Roger, but it tasted very good and after this I was ready to check out the neighbourhood. Mum wanted to unpack and sort out our small home, which I considered pointless until our beds arrived.

I said that I would like to go out and explore. It was obvious though that Mum was worried that I would get lost.

`Come with me,’ Granny said, solving the problem. `I can show him around and take him to our hut where Bert is and leave you in peace.

Come on Ronald.’

Happy to have something to do, I followed the bustling

figure of my grandmother along the path between the blocks of rooms. We came out near Kitchen No. 2, where our meals would be prepared.

The building on the left, she said, was the ladies’ shower block. We walked past the kitchen and across the top of Main Street, which ran south towards the main entrance. I must have walked near or on this road last night, and said so, but Granny thought that we would have taken a route along some of the blocks to the left. Main Street was lined with mature trees, some nearly 60 feet tall. We walked only a little way before turning left past Kitchen No. 1 and then a large dining area. Each side of us were blocks of accommodation rooms, but these blocks seemed to contain about a dozen rooms. At the ends of the blocks were linking walls, so the effect was a series of courtyards. Then we came to a raised road of random granite blocks. I asked Granny why. And she said that it would keep our feet dry when the summer rains came. Granny turned south along `Rocky Road’; I knew the direction from the position of the sun in the sky. Shortly after, we came upon a large space with no buildings but filled with different sorts of trees. Then, in front of us, was a large grey building with a bell tower in the middle tiled with the red tiles so common all over China.

The building on the left, she said, was the ladies’ shower block. We walked past the kitchen and across the top of Main Street, which ran south towards the main entrance. I must have walked near or on this road last night, and said so, but Granny thought that we would have taken a route along some of the blocks to the left. Main Street was lined with mature trees, some nearly 60 feet tall. We walked only a little way before turning left past Kitchen No. 1 and then a large dining area. Each side of us were blocks of accommodation rooms, but these blocks seemed to contain about a dozen rooms. At the ends of the blocks were linking walls, so the effect was a series of courtyards. Then we came to a raised road of random granite blocks. I asked Granny why. And she said that it would keep our feet dry when the summer rains came. Granny turned south along `Rocky Road’; I knew the direction from the position of the sun in the sky. Shortly after, we came upon a large space with no buildings but filled with different sorts of trees. Then, in front of us, was a large grey building with a bell tower in the middle tiled with the red tiles so common all over China.

`That building and the one behind it were classrooms,’ Granny said.

`Does that mean I am going to school?’ I asked.

Granny laughed and said `No, the rooms are now used as dormitories for Roman Catholic priests and nuns who arrived in Weihsien at the beginning of March.’

We walked round the end of the building to another open space, but this was filled with blackened and broken desks, and laboratory equipment. There were one or two internees picking over the burnt remains in case they could find something that might be useful. `Look, they have had a big fire, Granny,’ I said.

`Yes they have, but it was done by the Japanese Army about five years ago when the Japanese were fighting the Chinese, and they destroyed the school. Such a waste.’ She continued, `The American missionaries fled and the Chinese students were either killed or sent back to their towns and villages.’

`Why did they kill the students?’ I asked.

`They were innocent enough and harmless and would not have hurt anyone. But they were Chinese and there was a war on. Just like Japan has now declared war on us English.’

The block in front of us was also classrooms, but that too was now used as dormitories for priests and nuns.

`Where do you live Granny?’ I asked.

`Not very far away in Block 13,’ she replied.

`I am going to take you there as Grandpa should be back now from Kitchen No. 1. In the meantime I thought I would show you this area.’

`Why has he been at the kitchen? Surely, he doesn’t work there?’ I commented.

`Oh, yes he does. All the internees here at Weihsien have to do something for the Community, we have no servants like we all used to have before the Japanese came. I believe that the present rules excuse ladies with children under two and the one or two ladies expecting babies. I peel vegetables in No. 1 Kitchen.’ We carried on walking across the near open place with all the trees.

`Granny, why are there so many different types of tree in Weihsien?’

`Because, when it was a school and college they used to teach botany, and rather than show the students pictures of trees they let them see real trees. So many of the students came from Shandong Province where there are only small trees that could almost pass for bushes,’ Granny replied.

‘There is a big river north of us now which is called the Yellow River or Hwang Ho. From the time of Jesus until 1853 it flowed into the Yellow Sea a couple of hundred miles south of here. Then there was a big flood which killed off the trees in Shandong Province. When the water had all flowed out to sea the river had changed its course from a place called Kaifeng and flowed north-east to the sea which meant that the Shandong hills, where Weihsien is, became south of the river.’

`There is Grandpa going in to your room,’ I said as we entered the courtyard, defined by a wall between the ends of Blocks 13 and 14.

When we got to the room Grandpa was surveying the pile of blankets and clothes on the floor and the packing cases alongside one wall, which had arrived the day before. He was scratching his head and studying the mess in the small space, particularly the two dismantled beds in a crate. He looked up in pleasure when we appeared in the doorway.

After hugging me and asking after Mum, Dad and Roger, he took charge.

`I will show Ronald the camp,’ he said firmly, `while, you, Fanny, can tidy up this place. It looks as though a typhoon has swept through it. I will put the beds together when I can borrow the tools. Come along Ronald.’

He took my hand and I followed happily enough and we left Granny sighing heavily but getting down to sorting out their possessions, much as Mum would have to do when our trunks arrived, as she only had suitcases for the next week.

Grandpa was taller than me; he was sixty-seven with a head of thick white hair. The story went that he had been kicked by a horse at the age of twenty-one and went white overnight. I was not so sure. He had worked for years in China as an electrical engineer and Lloyd’s surveyor, and having spent most of his working life in north China he could not imagine life anywhere else. The upheavals of the last three years had hit him very hard, literally turning his world upside down. Leaving his Tianjin home in Meadows Road after nearly a quarter of a century had affected him deeply. However, to me he was the same as I had always known him and I skipped along happily as he took me walking through the camp that was to be home for the next two and a half years, although I did not know it at the time.

We walked along the front of the rooms that were in their block, through an open kind of arch, although it looked as though there had once been a door. In front, running left to right, was the Rocky Road that Granny and I had walked along, turning left past Kitchen No. 1 on the right. This area, Blocks 1 to 15, had originally been for those who had come from Beijing and Qingdao, but Granny and Grandpa had been put into that area, and hence they were allocated Kitchen No. 1. After we walked about 150 yards we came to a playing field, three-quarters the size of a normal soccer pitch, marked out as a hockey field with a `D’ shaped penalty area. There was also a softball square in the south-east corner.

`Nearly all sports are played here. They had to restrict themselves to a softball diamond because someone worked out that if they played baseball the ball would forever be hit over the wall,’ Grandpa added in explanation.

We turned right and walked past the Church. Grandpa went on to say, `The Church is used by all Christian denominations. I think at the moment there are about 250 Roman Catholic priests in camp and nearly the same number of nuns, which with the Catholic congregation makes about 600 Catholics. Then there are about 600 Anglicans and 900 other Protestants.’

`That is about 2,100’ I said, doing some rapid mental arithmetic. I had been brought up to learn up to the 12 times table and been encouraged to repeat it almost daily, so juggling figures was never a chore.

`Yes, so you see that if all go to church there have to be services each hour of daylight on Sundays. Which to my mind is a good thing, because sermons have to be of the seven-minute variety. And in a way the clergy are quite happy in these difficult times, as more turn out than usual for the services.’

Just past the Church was Main Street, and as we crossed it I could see the guardroom on the right and the closed gates that we had come through when we had arrived down the hill to the left. Although that was only yesterday it seemed as though it lay somewhere in the distant past. In front of us was Number 3 Kitchen and some rooms backed up against the outside wall; these seemed to have been accommodation allocated to missionaries who had been at isolated mission stations.

The first buildings were the camp offices and the Commandant’s Office. Grandpa hurried through these. I somehow felt that Grandpa was frightened to be seen by a Committee member and hauled in to do a job, which he was a few weeks later when he was roped in to sort out the electricity distribution. Grandpa did point out the post box and said that the Japanese allowed letters to places in China using the Chinese postal system, but they had to be addressed in Chinese characters. However, letters to England and America had to be written on Red Cross forms and placed in the box in the office for censorship.

Then past some more accommodation used by Catholic priests from the towns and cities in the hinterland of China. The camp wall continued with another watchtower and I saw a guard at the top carrying a rifle. Opposite, well within the camp was the `Sunnyside Hospital’, which had been built in the past twenty years. It was three stories in the front but having been built on a semi-cliff, as the ground dipped down to the river, the back was only two stories.

`Grandpa. Why is what you have called the hospital in such a dirty state?’ I asked.

`The building was gutted and looted in the fighting between the Japanese and Chinese in 1937-8. Sadly most if not all the patients were bayoneted. That has been cleared up but the electric wiring and plumbing was all ripped out; it will take a lot of work before it can be used again as a hospital, although the top floor has been appropriated by Catholic priests for living accommodation. I suspect that you can see the fields from their windows, as the priests have devised a means of signalling to Chinese outside the camp. You can see that all the medicine has been poured away and pills are ground into the floors. Just wanton destruction.’

`What is “wanton” Grandpa?’

`It means needless, unnecessary.’

As we climbed up the slope of the ground, Grandpa added: `You can see a couple of tennis courts and a basketball field. I suspect that was devised by the American Missionary Doctors to get patients to recover with exercise. Whilst basketball can be quite lively a game it can also be quite gentle. Americans are very keen on it.’

`Did you play basketball, Grandpa?’

`No,’ he replied, laughingly, `I am too short. One needs to be well over 6 foot to play properly. Even your Dad at over 6 foot did not, he concentrated on rugger, ice hockey, and recreational tennis with your mother.’

By now we had come to a little doorway, going through it there was a small field edged with trees. This seemed to have been taken over by Catholic priests, who were walking to and fro reading from their prayer books. I realised that they were saying their `Office’. It was a poor substitute for cloisters, but better than nothing. There was another doorway in the corner and this led to a sort of passageway between the wall that separated the internees’ part of the camp from the comfortable-looking, two-storey Japanese quarters, originally the Missionaries’ Houses. The right wall just split off some more accommodation and a small field which I could see had mulberry trees. I recognised these from Beidaihe, and I knew that their berries were delicious and that the trees were ones you could climb. The rather useless acacias had very brittle branches, as I had found to my cost the last year in Beidaihe when a four-inch branch had snapped under my weight. I had been warned by Art, but in my usual manner of disregarding elder cousins like adults I had to find out for myself, fortunately with no broken bones. The acacias in Weihsien I identified as being too tall and thus unsafe, higher than about 12 feet.

As we are now quite close to your room I will take you back to your parents,’ Grandpa said, as I recognised the back of Kitchen No. 2.

Roger was playing in the dirt outside our door with some coloured wooden blocks that had been packed for him in my case. I squatted beside him, as he had also been given my `official’ toy, a metal ambulance about 12 inches long. I don’t think that Mum had found my toy soldiers which I had smuggled on to the train, and still had. Then Grandpa went inside to speak to Mum.

The first few weeks we lived in Weihsien was a period of adjustment for everyone. I ran around freely with little parental supervision and played with the children living in and around the neighbouring blocks; in fact those first three months I tended not to wander too much from our room. The organising of schools was put into the `difficult’ tray, it was going to be too hot and there was no obvious building to use.

In normal times the next term would not have started until September, and anyway things might be different then. Our parents had a far worse time of it, trying to get accustomed to life in such restricted confines. In fact the room that we lived in seemed smaller than the enormous cupboard in which Mum had kept her clothes in Tianjin. Until our heavy baggage arrived we had to sleep on the floor, but fortunately Mum was able to borrow a cot, brought in by an expectant Mum who would not need it for a few months. That stopped Roger waking and grizzling on and off during the night. Otherwise I enjoyed sleeping on the floor, especially as I could keep my clothes on.

It was difficult trying to keep Roger clean; Mum washed his nappies, but I was left to my own devices. All the adults had had their luxury lifestyles abruptly terminated. The ladies suffered much more, doing their own chores. They had always been spoiled, with servants to do the domestic work.

In about ten days our trunks and beds arrived, dumped on the road near Kitchen No. 2. There was a general feeling of `I’ll help you if you will help me,’ and the items got put on the ground in front of each room. The trunks had been broken into, but as they were mostly clothes nothing much had been taken.

The beds were intact but three full-sized beds and a cot would take more floor room than our room possessed. My parents realised that the only solution was bunks. The packing cases had to stay on the ground until they were dismantled, and the beds assembled. That was not an easy process as the door was too narrow to take an assembled bed unless turned on its side! Borrowing a claw hammer, Dad was able to retrieve the nails from our crates and straighten them on a stone.

Then Dad needed to borrow a saw. Our next door neighbours were Dr `JW’ Grice, his wife and their daughter Susie, who was about three years older than I. Dr Grice offered a saw but Dad declined on the grounds that `It might be needed to take a leg off someone.’ Dr Grice was the family GP in Tianjin and `JW’ and Kay Grice were good friends of my parents; he had been a British Army doctor during the First World War and sometimes could be persuaded to talk about the Mesopotamian campaign. However, in Rooms 2 and 3 of our block were the Dunjishahs. There were three daughters, Thritie, Katie and Frennie. Thritie was a bit older than I, Katie six months younger and Frennie two years younger. Mr Dhunjishah, who had been manager of the Talati House Hotel, had a complete carpenter’s tool box, and Dad had no qualms borrowing his saw for the morning to cut up crates to make the beds into bunks. Dad opted for a top bunk with one below for Mum, her back still troubling her, whilst Roger and his borrowed cot had to stay on the floor. Thus I was made an upper bunk with long legs so that the space below could be used as well for the pram. I was always dubious at the stability of the arrangement, but did not fall out and it did not collapse.

It was right across camp to Block 7 where the men’s showers were. When to go and have a shower was decided by Mum, when she often issued a tiny square of soap. My reaction to start with was `Why can’t I use the women’s as they are much closer?’ I was firmly rebuked for that thought and told that I was too old. Dad cut in to say he was going to the shower block and that I could come too. The shower block had a water tank built on a tower with a pump at the bottom, which was manually pumped by sixteen- to nineteen-year-old boys, so that the tank was filled and the water pressure gave what was considered a decent shower. When I first tried them I discovered that the water was `cold only’, too uncomfortable and as there was no other soap than a battered bit of carbolic which had been used by dozens, it seemed better to stay dry, unwashed but comfortable.

I also sneaked into the men’s lavatories near the playing field when caught with the need, the urinals there basic but useable. One day I heard Mum having a whispered exchange with Dad on the subject, and he had told her quietly `Don’t let him go there, Margot, he can use your ferry in the hut here for the time being. The nearest “gents” are just not suitable for youngsters yet.’

Naturally this aroused my curiosity, and as soon as I could get away from my parents I did so. I recruited my new Weihsien friend, Joe Wilson, who lived in Block 41 Room 1, across the path from us but in the same compound. Joe was eighteen months younger, but nonetheless someone to play with. Anyhow, we found our way to the men’s toilet block near the end of Block 23. It smelt pretty unpleasant as we approached and on entering found out why. There were no toilet units or seats, just shallow square cement `basins’ with two raised foot plates each side of a hole in the middle. There was no cistern and the means of flushing was a bucket which was filled under a pathetic tap in the far end. The whole place was running with sewage and even we, scruffy schoolboys, were horrified. There was a man taking his trousers down balancing on the foot rests, trying desperately to keep his trousers out of the various liquids, he shouted at us to get out as we stood gaping, whilst he bent and tried to align himself with the hole in the floor. We fled giggling and took to doing what we had to do against the toilet block wall, having made sure we were not seen. As to my father’s edict I had no intention of using a potty, which I considered was for babies only. Mum could make her own arrangements, but I was not going down that route.

`I do not know what the fuss is about, Joe,’ I said, `The facilities are no different to the ones we provide for the servants in Tianjin, although we do give them a short piece of hose with a working tap. Puzzles me, where do they keep the paper? It can’t be in reach’ I continued. And then changed the subject.

After a few weeks the loo problem was largely cured. Amongst the camp inmates there were engineers of every kind, architects, builders and designers, not to mention doctors and teachers. Some form of engineer rigged up a way to flush the formerly un-flushable and we were allowed permission to use the cleaned-up facilities, with the caveat being `only when wearing shorts’. When I looked puzzled, Mum said, `If you go in there and try and take long trousers down you will get them into the filth. And, you will then stink and I am not washing stinking trousers. You know there is no laundry. The Japanese had one about six miles away and people started sending sheets and towels, only to find that they came back both torn and dirtier than they went in, if they were indeed returned. So we ladies have decided to boycott the laundry until a better one is provided.’

During April and May us boys kept clear of the blackened rubbish tip, which was adjacent to Blocks 23 and 24 yet only just over the wall from Block 41; there were too many adults trying their hands at scrounging bits to salvage. This pile of partly burnt furniture and laboratory equipment I had first seen on my walk with Granny the day after we arrived. Joe and I with one or two others used to sift through the ash to see if we could find anything for us to play with. We had got the idea from adults who had salvaged half-burnt furniture and repaired it to make it useable. Dad had even used some of the wood to make the headboards of our bunk beds. The certainty, to us boys, was that you got filthy, but by then we had worked out that if you finished by five in the afternoon you could get down to the showers and have a near hot shower because the sun had heated the water in the tank. Leave it any later and the adults had used all the warm water.

Soap was still a problem but one could rub hard, which was the only solution Mum had to offer. What little soap she had she needed for Roger.

One day towards the end of April, after the adults had given up on the area and removed anything of use or value, we came across some shards of broken glass. Joe cut himself and yelled, but I was too busy digging out something much more interesting, something different from below the glass.

`Look what I’ve found,’ I crowed in delight. `I think it’s an engine or something like that.’

`Does it work?’ asked Brian Calvert seriously. `I bet it doesn’t work.’ Brian was six months older than I but we had known each other for years. In fact the last birthday party that I had been to was his in Tianjin. He now lived in Block 17 on the opposite side of the camp.

I tried to run it along the ground without much success. `No, not really but I can still use it with my ambulance. I think the model is some sort of steam engine.’

`What would they use those for in a laboratory?’ Joe asked curiously. We had all been told to keep away from this part of the rubbish pile as there was a lot of glass from broken laboratory equipment.

`Maybe they did experiments with steam engines,’ I suggested, not having much idea.

`Possibly, better than this book anyway,’ Joe muttered. He had found a half-charred physics book and was trying to decipher the symbols and make sense of it.

I was admiring my new toy when I was pounced upon from behind and the engine snatched out of my hand by a larger boy whom I did not recognise, from yet another part of camp. A scuffle followed and we both fell into the bonfire ash whilst we wrestled for possession of the treasure. I won but not before I had got myself covered in dirt. When I got back to our room Mum was horrified, but I was triumphant, although battered.

`Look at you,’ she cried. `We have very little soap and I have to wash everything by hand on a washboard in the washhouse. Roger’s nappies take a lot of time and precious soap. How could you get so dirty? You are not to go and play near that bonfire again.’

Unfortunately, Dad backed Mum up, although I think that he thought it was quite amusing when I explained indignantly that I had only fallen in the ash because a bigger boy had tried to steal my trophy. But the ash pile was out of bounds at least for a few days, until my parents forgot about the incident.

Joe and I moved our operations to another part of the camp, nearer a kitchen where we could smell food even if we could not have it. One day we found a paper sack of very light grey powder, slightly torn but discarded behind a building near some low bushes, and smuggled it back to Blocks 41 and 42. We got some water and found that if mixed with earth it made perfect modelling clay which was quite hard when dry. We spent a whole day making several masterpieces.

A couple of days later we were found by an American man, who at first admired our efforts, then got rather upset when he read the label on the bag. `Hey kids, this stuff is cement,’ he told us so loudly that several other men were attracted to the scene. `What the hell are you doing playing with this? We can use this for building. You had no right to mess with this.

...

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/NoSoapLessSchool/book(pages)WEB.pdf

#