chapter 1 ...

THE ORIGINS OF A VOCATION

Translated by Albert de Zutter

A Liège Family

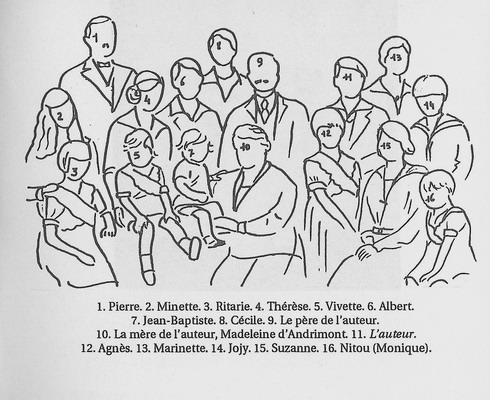

I was born in Liège, Belgium, on June 15, 1915, along with a twin brother, Albert, a confirmed Liègeois, both in business and in politics. He was treasurer of the Liège city government for 12 years. He was the father of five children and five times a grandfather.

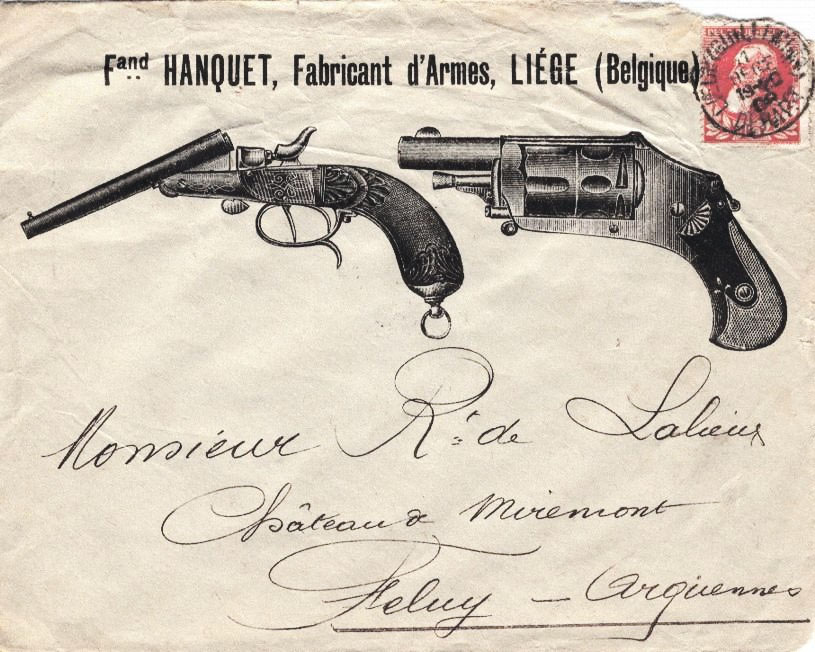

My father was a manufacturer of hunting firearms. Along with his brother, Paul, the family patriarch, he profitably ran the family industry which was founded in 1770 by a great-great grandfather, Martin Hanquet, an iron merchant. They went from making forged nails to making knives and swords, then to flintlock muskets, and finally to modern day hunting firearms. The Liege factories were known for the excellence of their work.  Their arms had an international reputation – in Asia as well as in South America or Africa. As a child I often received from my father envelopes filled with stamps from the daily mail. In examining them and in seeking to know their countries of origin I developed a taste for distant countries, and without conscious effort learned a practical geography that encompassed Uruguay, Indonesia, Malaysia, Ceylon, Morocco, the Congo and the French colonies.

Their arms had an international reputation – in Asia as well as in South America or Africa. As a child I often received from my father envelopes filled with stamps from the daily mail. In examining them and in seeking to know their countries of origin I developed a taste for distant countries, and without conscious effort learned a practical geography that encompassed Uruguay, Indonesia, Malaysia, Ceylon, Morocco, the Congo and the French colonies.

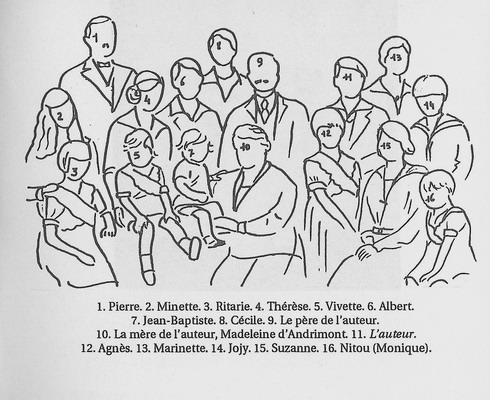

My mother came from a family of engineers and followers of the law and, She, however, did all of her studies at home with a female tutor, except for her final year in Paris at the Convent of the Birds, a well-known finishing school for young girls of respected families. Married at age 20, she learned her role of wife and mother in her daily experience and in the course of her 15 maternities. She was blessed with good health, as was my father. Nevertheless, after her twelfth child, she hired a nanny who became a second mother for us. There was a gap of 21 years between my eldest brother, Pierre, who became a judge in Liege, and my youngest brother (also my god-child), Jean-Baptiste, now a retired banker.

When my mother was almost done raising her children she was often sought out as a speaker on what she had learned by experience, and to lead conferences, first in Liege and then across the country. My mother wrote very well and had beautiful handwriting, readable and firm. Her conference presentations were published during the 1930s and filled three volumes, which other mothers benefited from reading. “Si les mamans savaient” (“If Mothers Only Knew”) was her first book. Subsequently she published “Simplement vers la joie” (Simply Toward Joy), followed by “Le bonheur au foyer” (Happiness in the Home). I owe much to her, especially my optimism. She listened patiently to everything we wanted to confide in her and seemed always to be available to us. Yet she did reserve a time for her husband, the half-hour between his return from the office around 6:30 p.m., and the start of supper. It was a time devoted to exchanging information and sharing, as we would say today. My father would tell her about his day and my mother would tell him of her activities and anecdotes about the children.

A solid foundation

My father managed his large family – there were 15 children – with authority and discipline. He never raised a hand to us, but a look from him and his pointed mustache was sufficient. Each morning, starting at 6:30, he made the rounds of his children’s rooms, opening the doors and chanting, “Get up, get up, the dawn has already risen.” He had already shaved and was half dressed. Twenty minutes later he led his troop to our parish church, Saint-Jacques, 200 meters from our house.

Saint-Jacques was a superb church in a flamboyant gothic style, formerly the abbatial church of a Benedictine monastery. It had a colorful vault decorated with human figures that distracted us and caused us to daydream. In the winter, by the pale light of the gas street lights, we would trot to the church to attend the 7 a.m. Mass. At that time church did not lack for faithful at weekday Masses. We would find other families there, friends of ours, but we only stopped to chat after Mass on Sundays or after an evening Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament or a feast of the Virgin Mary. Otherwise we were too pressed for time.

At that time the churches had chairs covered in velour for those individuals and families that had paid a fee for them. My father restricted himself to installing his children on chairs with straw seats at the head of the center aisle. We received communion at the beginning of the Mass, as we had to leave before the end to hasten back home. In the meantime, my mother had prepared big piles of buttered bread which we devoured with relish, complemented with coffee with milk, but no sugar.

The girls left the house first, at 8 a.m., because they had to join the ranks of Sacré-Cœur students, who were met at 8:10 next to Sainte-Veronique Church before climbing the Cointe Hill to the Bois l’Evêque Convent. Eight of my sisters did their studies at Sacré-Cœur. Three of them decided to stay there for life and devote themselves to teaching in Belgium and in Zaire.

Only one of my sisters escaped to a conventional life, no doubt because she was so close in age to my twin brother and me and a younger brother (killed by the Germans at the liberation of Belgium in 1944), and was a part with us of a closely united foursome. For the first three years of primary school the four of us went to a school taught by the Daughters of the Cross. My sister, Marie-Madeleine, continued there, studying the classics, after which she became a director of literature (regent litteraire) and assistant dean (assistante sociale). It was she among my sisters who was the most traveled as she was a member of a very modern religious society, although it was founded during the French Revolution, the Daughters of the Heart of Mary. She was called to establish or direct schools in the Congo, Spain, Japan and Chile.

As for my brothers and me, from our ninth year on we attended the College Saint-Servais, run by Jesuit Fathers. We were terrified of failing, and so we applied ourselves to avoid that possibility, studying enough to succeed without difficulty. My father was perturbed by the rare occasions when he had to meet with our professors. One time, however, he did decide to intervene. We had just enrolled in an advanced Latin course, and Father O’Kelly, our professor, gave us blue cards every two weeks for our homework – that is to say a barely passing grade or mark. My father didn’t like that. He went without telling us to meet with the good Father, who proceeded to tell him the reason for his severity: “These twins copy their homework from one another.”

“Wrong,” said my father, “they don’t copy from one another. They work together.” It happened that being true twins, our intellects developed in the same fashion.

“You will see,” said my father. “Just wait for the exams.”

In fact, when the examination results arrived, the professor had to admit that they were almost identical, even though he had placed us far from one another. From that day he was convinced and changed his opinion of us.

Ninane

As we were a large family, we didn’t travel, but we did like to be in the great outdoors. My parents, from the time they bought their property in Ninane (10 kilometers from Liege) in 1924, were motivated to enlarge that pretty country lodge, adding a second story with a “Mansard roof.” (Translator’s note: “Toiture a la Mansarde,” a style of hip-roof popularized by the French architect Francois Mansart, having two slopes on each side, the lower slope steeper than the upper). That added nine rooms which enabled an already large family to welcome cousins to take advantage of the summer. We would gather there on Holy Saturday, after religious services faithfully attended at Saint-Jacques parish, not far from the residence of the bishop of Liege. The house had only the comforts of a true country property – neither central heating nor running water in the rooms. But we put up with those conditions to come together often in the living room where a wood-burning stove warmed the air. Springtime came on quickly and caused the blossoms and flowers to burst forth, and starting in May, we concentrated on playing tennis at our gathering place on Saturday afternoons. We also engaged in other sports – group swimming, bicycling and football (soccer), and most of all hikes to the passes of the Ardennes, ending up at the neighboring villages of Beaufays, Embourg and Henne, among others.

On All Saints Day, we returned to Liege. We lived in a house at No. 4 Rue de Rouveroy, a house belonging to the Cathedral parish. When the family grew, my father rented the house next door, with a connecting passage on the second floor, thus augmenting the number of bedrooms.

Acolyte

I served as an acolyte in our parish and also belonged to a small choral group that sang on important occasions. I have a memory of having sung the Gregorian chant, Lumen ad revelationem gentium at Candlemas on February 2.

There was no lack of convents in our neighborhood, close to the seminary. Parish priests and assistant pastors celebrated early morning Masses there, starting at 6:30 a.m. or 7 a.m. My twin brother and I were often asked to serve Mass for these unscheduled celebrants. Doing that regularly from the time I was 12 made me an early riser.

We had two associate pastors in our parish. The elder, Father Rixhon, supervised the Mass servers. He would have us meet weekly and hold a little liturgical seminar to familiarize us with the practices popularized by the Benedictines and their missal – the last word in prayer books. It contained all the texts for prayer and liturgy through the year. We were happy and proud to receive that missal on the occasion of our first Holy Communion, and we never failed to use it when we went to church. In her youth, my mother had decorated a pretty dresser with four shelves. That was where we stored our missals, close to the coat closet in the entry hall.

Family piety

In addition to daily Mass, we also faithfully engaged in family evening prayer. We did that on our knees in the living room immediately after our evening meal, which we always referred to as supper.

My father led the recited prayer, which was always the same, and delivered the introductory line, “Let us place ourselves in the presence of God,” after which we would continue. The prayer included an examination of conscience, and a short, silent pause to permit us to analyze our daily actions for sins. That period never lasted very long and I have very little memory of having searched through my days to recall my sins. Religious holidays, like Sundays, were occasions for rejoicing and taking walks. All the family would dress in their Sunday best. Papa liked to emerge with his children and lead them on “le tour des ponts,” literally the tour of the bridges – a promenade that would take the better part of two hours.

It would also happen that on a Monday after Easter or Pentecost the extended family – including aunts and uncles and their children – would plan a picnic in the Ardennes, or one might say a pilgrimage. A trip to Chevremont, where one could pay homage to the Virgin represented by a small, miraculous statue at the top of a hill was their favorite. Another favorite was the cemetery at the base of the hill where the Hanquet grandparents of Coune a place of prominence in the underground family sepulcher.

In 1931, having left behind the great economic crisis of 1929, my parents celebrated their silver anniversary and decided to take us all on pilgrimage to Lourdes, a grace-filled endeavor in which cousins and friends joined to fill a special railroad car reserved through the offices of my eldest brother. Our pilgrimage coincided with the traditional Belgian exodus in the month of August. It was our first family voyage beyond the Belgian border. Our pilgrimage merited a special audience with Monsignor Gerlier, the bishop of Lourdes who later became the Primate of France and the archbishop of Lyon. The souvenir photo was taken at the foot of the altar in the enclosure reserved for devotion to Mary.

Scouting

When I was a child, the Boy Scout movement appeared in the cities of our province, but not yet in the secondary schools. I owe my awakening to and formation in the values of Scouting at age 13 to Father Attout, a Benedictine of Maredsous, founder of the Lone Scouts. For my first Scout camp I was infected by the Scouting virus. But it would require a year of participation for me to take the Scout troop seriously, because I was so happy with my family situation. But Scout master sounded off and told me that if I did not attend regularly and apply myself at the meetings I would get nowhere and it would not be necessary for me to continue. I think that he aroused my own love for the movement and put me in touch, without my knowing it, with a value that was well anchored in me already – fidelity.

I was won over, and I think I never missed a single meeting after that day. Later I became the leader of the Sangliers Patrol. I thus assumed one of the most pleasing tasks that can be entrusted to a youth of 15 – responsibility for seven boys barely younger than oneself. It amounted to a school of generosity and devotion, of energy and surpassing one’s self, of smiles and joy, of brotherhood and feeling for the other, of adventure and discovery.

One cannot praise too highly this pedagogic method launched by Lord Baden Powell, one that continues to bear good fruit 80 years later.

Skipping over two years: I am student of law at the University of Liege. The chaplain of our Scout troop in which I am an apprentice leader, asks me to come and help him. His Scout totem is “Dragon.” He has started a Scout troop at the Liege high school. They are having their first camp-outs, but are having trouble getting started because they lack experienced leadership. Father de la Croix, Dragon, asks me to come and help. There is already a troop leader, Honore Struys, a well-intentioned boy of Flemish origin, a little older than me, but he knew nothing of the Scout leadership method. I innocently believed that I was well versed in it as I had just completed a two-week instruction camp at St. Fontaine in Condroz and was about to receive the Wood Badge, the official leadership certificate.

But I had to become acquainted with the culture of the public school students, a world which I had yet to discover. I must say that at the time, the separation between official education and Catholic education was very clear and my family was known in Liege as stout defenders of independent education.

Dragon encourages me to explore this new scholastic milieu, less bourgeois than my own Jesuit environment at the College Saint-Servais in Liege. He urged me to discover and adapt. “Go and visit the parents of the new recruits,” he said. I obeyed, and began those visits, a practice that I continued for a lifetime, but with other motives.

“Teach my son to cut the crap and grow up,” one father said in language that was quite direct. I never forgot that assignment. But it took me several months to understand that the appeal of my gentlemanly dress and manner which I displayed a bit too obviously did not go over with these young Scouts who early on dubbed me the “kid glove assistant.” They worked to roughen my edges and slowly I won over their hearts and their friendship.

We had regularly invited three young Chinese boys who were studying in Belgium to our campouts: Andre Shih, student at Malonne, and the Liao brothers from another secondary school. These secondary school students talked to us about their country and customs. They taught us to eat with chopsticks and showed us how to write our names on the chopsticks which we fashioned then and there.

The following year as winter approached the troop leader entered the seminary and I was named to replace him. Our project was to prepare for Christmas. Dragon, aware of his responsibilities as chaplain, keenly wanted to lead his Scouts in a (spiritual) retreat. But where and how? The idea interested us but our means and resources were limited. It might be able to do it if we could find a country house in the vicinity of Liege. I thought of the house owned by my parents who were always welcoming and generous. I ventured to ask their permission to use most of the rooms of the family’s country house which, while it was large, was heated only by wood-burning stoves in two of the ground floor rooms. My parents were receptive to the idea and I in turn guaranteed the good behavior and propriety of the Scouts.

So, about 20 of us arrived in Ninane a few days before Christmas. I had somewhat underestimated the amount of work that would be involved. While Dragon went to the church three to four times a day to instruct the Scouts, I had to make arrangements and prepare the food, all the while trying to keep up with the retreat. This was no small task. I also had to attend to housekeeping. It was time consuming, but the Scouts did cooperate.

The grace of the call

It was during this time of activity and serving of others that the Lord granted me the grace of his call. I well remember the time and place. I was praying at the communion rail in the church. It was there that the question formed in my heart, posed by Jesus: “And you, what if you gave all your time and all your life to my service?” Needless to say, I hastened to banish that startling challenge which was so troubling for my future plans (I was planning to go into the family business). But the question would not be denied. The honorable thing would be to take counsel and respond.

I revealed my dilemma to the chaplain, who counseled me to pray and ask the Holy Spirit to clarify things for me. Weeks passed, and my decision to go to the seminary and become a priest in the service of God and man ripened slowly. Life was good and it would be even better if I lived it entirely on that course.

It remained to choose a seminary and the field of my apostolate. The Scout Dragon, while he served in St. Jacques parish in Liege, was also connected to a new missionary society, La Societe des Auxiliaires des Missions, SAM for short. It was founded six years earlier to provide help to the first Chinese bishops. We held our Scout meetings in the attic of the house the Dragon lived in. A number of Chinese students would come to that house to read Chinese newspapers and magazines kept in a room on the ground floor, next to the priest’s desk. Dragon (Father de la Croix), a great apostle, had his own style ― a bit bohemian but very direct and welcoming, which was attractive to young people. I met with him often to prepare meetings and other Scout activities. It was with his help that my choice matured and I decided to apply for admission to the SAM seminary in Louvain. I spoke to no one except him about my choice. He advised me to wait until the end of the year examinations at the university where I was completing my second year in law. Only then did I speak of my decision to my parents and that I officially announced my decision at the conclusion of a memorable Scout camp on the banks of the Helle in the Eupen region.*

* Scouting, the environment in which my vocation blossomed, continued to follow me. After my Liège troop and the public school troop, I started another troop at Gembloux during the time of my seminary studies, before living through a similar experience with the youth of the concentration camp in Weihsien (see passage later on regarding the clandestine Scouts). In fact, it was not till 55 years later that I concluded my service to the Scouts, after 35 years of work with the Lonescouts.

At the end of September in 1934 I enrolled in the SAM seminary at Kareelveld, across from the Mont-Cesar abbey outside the ancient walls of Louvain. There was a lot of talk about Father Lebbe. He had launched the idea of the SAM foundation in 1926 at the request of first six Chinese priests to be ordained as bishops. A handful of young men from Verviers responded to Father Lebbe’s call and placed themselves under the tutelage of a former Verviers parish priest, Father Andre Boland. It was Father Boland who acquainted us with Father Lebbe, assigning us to read the files he had accumulated on the subject.

The seminary had a particular cachet reflecting the fact that there were only about 20 seminarians and that Father Boland practiced a system of trust. He wanted us to develop our own personalities and make our own decisions, speaking to him about them after the fact. He practiced an open-door policy every evening after prayers and, while having a cup of Chinese tea, guided our nightly conversations. I completed four years of seminary – a short time, yet it was judged sufficient by my superiors as formation for my priesthood and my future life as a missionary. I was ordained to the priesthood on February 6, 1938. I left for China at the end of November that same year.

#