TANGLING WITH THE JAPANESE

Translation by Michael Canning

First Imprisonment

It is the 12th of December 1941. It has been freezing for several days and I have had a barrel-shaped stove installed in my big room which will take the edge off the cold during the winter, although the temperature will never go above 12 degrees centigrade. It is of truly local manufacture, built out of dye barrels from Germany. It is coated with clay, and has a little window at the bottom and a 10 cm circular opening at the top. A stovepipe made out of tin cans is fixed over that hole.

Visits from nearby Christian groups began on the 15th of November. Already the thirty or so surviving Christians from the town communities have responded to the call of their parish priest. They have submitted joyfully to the rules and customs which require them to come and fulfill their Easter duties and refresh their religious knowledge during the winter months and not at Easter as is the practice in Europe. After sunrise they attended mass with a sermon. After returning home for a quick meal they returned in groups of between six and ten to go over their catechism and to make confession.

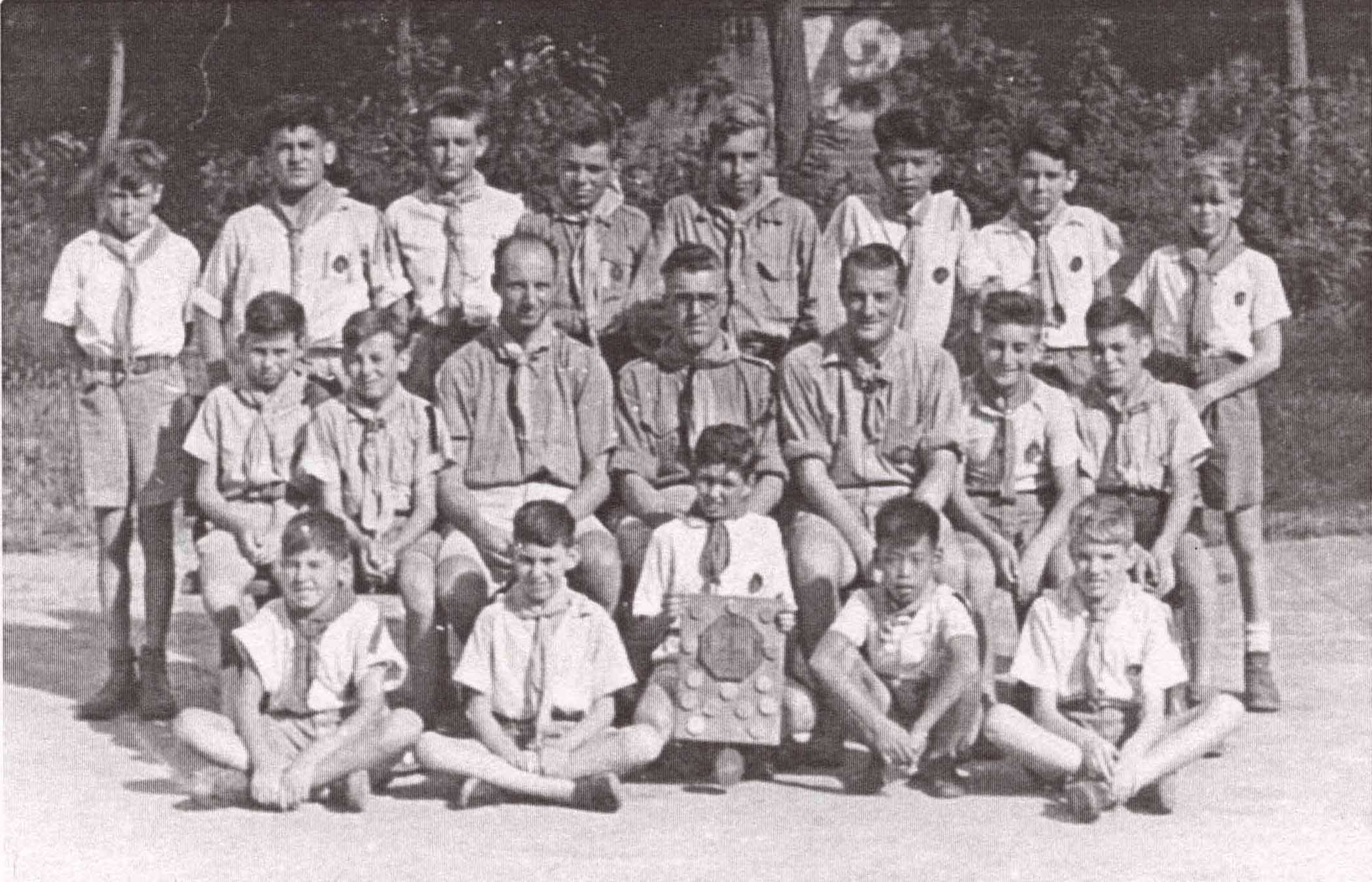

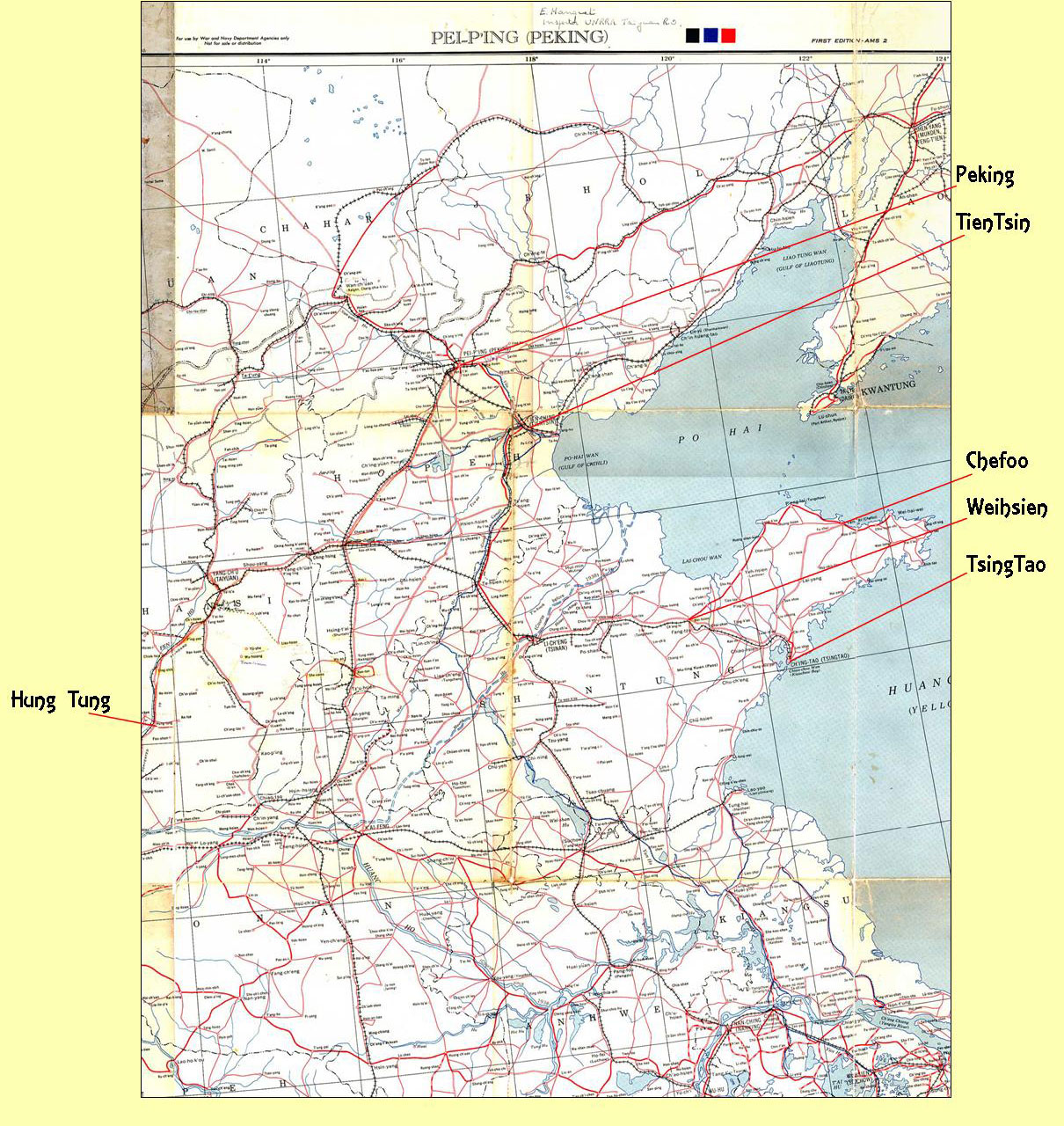

The town of Hungtung (36°15'56.0"N - 111°40'31.0"E) is nine tenths empty. Just a few shops have reopened their doors in the main street which runs between the North and South gates. There is a barber, a dentist who is more of an artisan than a craftsman, a photographer who is just about capable of supplying photos for identity papers, two pharmacist-cum-herbalists who sell Chinese remedies in mysterious little packets, a seller of Chinese sweetmeats and a hardware store whose stocks are limited to thermos flasks and oil lamps with bluish glass bases. Three or four sellers of fabrics share between them the best stalls and one reaches them down a few steps off the main thoroughfare which is raised up at this point. These shops open late in the morning and close early in the evening - let us not forget that there is a war on - with the help of big wooden shutters which cover the displays.

The Catholic mission buildings are situated in the north of the town and are built against the town wall, which dates from the middle ages, not far from the North gate. They spread over a large area and comprise four or five courtyards surrounding the cathedral church, which was built by Dutch Franciscans.

The Catholic mission buildings are situated in the north of the town and are built against the town wall, which dates from the middle ages, not far from the North gate. They spread over a large area and comprise four or five courtyards surrounding the cathedral church, which was built by Dutch Franciscans.

Immediately on the east side of the church there is a big kitchen garden where my servant grows spinach and beans, as well as some carrots and leeks for wintertime. There is also a deep well whose water is barely drinkable. It has to be boiled first, and even then it tastes of saltpetre… Also in the kitchen garden there are some little mud huts in which my predecessor had stored - or rather hidden – some tens of kilogrammes of unroasted coffee sealed in oiled goatskin pouches. I discovered them the following summer. What a godsend they were at a time when you didn’t even have what it took to make a cup of tea. That discovery would allow me to give a surprise hand-out to all my colleagues!

Beyond the kitchen garden there is a yard surrounded by walls and by the buildings of a girls’ school. I almost never venture there as it is occupied by an unmanageably lively billy-goat for whom one or two wives need to be bought…We shall have to go to extreme lengths to find such nursing mothers, which are very rare in the area, to help Monsignor Tch’eng who, according to his doctor, needs to drink a lot of milk to help with his diabetes.

But let us return to the secondary entrance to this complex. The door is set in the western perimeter wall, down a cul-de-sac. A discreet Chinese doorway means that it usually goes unnoticed by passers-by. My presbytery – a cavern, or more exactly a house in the shape of a cavern – stands on the south side of this entrance. It is flanked by a covered gallery supported by wooden pillars; and it has a flat roof, where clothes or grain are dried, which is reached via an outside staircase running up the side of the perimeter wall. This is the oldest of the mission buildings. The inside is arched, and is cool in summer and relatively warm in winter. The floor is of cement slabs, and the walls are whitewashed. My bedroom is to the right, and straight ahead there is a vast study or office. Another little Chinese doorway opens into the presbytery courtyard.

If you walk north towards the high town walls on which from time to time you can see a Japanese sentry, you pass into the main courtyard which served as the bishop’s palace before Monsignor Tch’eng and his priests fled from the town and took refuge 20 km away in the mountains, in the village of Hanloyen. This courtyard is in typical Chinese style: the main building on the north side contains the reception rooms, while the buildings on the east and west sides are used as living quarters. There is a covered gallery which permits you to move from one building to another when it is raining without risking a drenching!

On the afternoon of 12th December 1941 I hear the dreaded sound of boots in the cul-de-sac leading to the mission: only the Japanese wear boots…The doorbell rings. Yulo, my servant, goes to open the door. There are two Japanese police, escorting twenty or so seminarists and seven or eight priests whom they bring into the palace courtyard. I am requested to join them there and to bring a minimum of belongings, which I hasten to fetch from the presbytery. While the police put seals on all the doors, we are told to settle ourselves as best we can in the north and west buildings flanking the main courtyard. We do not yet know it, but this is to be our prison for four months…Luckily, Yulo is allowed to stay in his own little courtyard near the kitchen garden. It is he who will see to our food and who will make some discreet contacts with the outside world for us. To house the seminarists the teaching building to the south of the church is reopened . Everything has to be cleaned, and there is no provision made for heating or food, since I am the only remaining inhabitant and guardian of the complex. Now we have all of a sudden thirty people to house and feed!

We are under very tight surveillance: communication between us and the seminarists is forbidden, and military police guard the two gateways giving access to the street and to the cul-de-sac. Fortunately we are allowed to talk to one another. Each of us has chosen a corner to open up his little bundle, and wide benches retrieved from here and there will serve as beds.

We lose no time in checking the position with our bishop. Why have we been arrested? How long are we going to be detained? All the diocesan authorities are here: the bishop [at the time, canonically speaking the prefect apostolic]; his vicar general; the procurator of the mission; and Monsignor Tch’eng’s counsellors. We need to see to the essentials and promulgate any new arrangements so that the life of the prefecture apostolic can continue in the outside world. We have to name an interim replacement for the prefect, who is not going to be able to function. The bishop charges me as his secretary to draw up a nomination designating Father Han as vicar general of the prefecture. He is the parish priest at Tupi and we shall try to get his nomination to him via my cook.

Paper is scarce, very scarce. In any case we have to be circumspect and leave as little evidence as possible of what we are doing. With this in mind I draw up this appointment in Latin, at the foot of a page in a school exercise book, and in my capacity as secretary countersign it below Monsignor Tch’eng’s own signature. The whole thing is a little strip of paper about 20 cm long. I entrust this tiny ribbon to Yulo who gets it to Father Han by hand of a Christian neighbour.

After dealing with that which has to be dealt with, we find ourselves killing time by making Chinese chess sets out of grey paper. I shall even, in the days that follow, manage to fashion a pack of playing cards using visiting cards found at the bottom of a drawer.

Alas Monsignor Tch’eng, Father Kao the vicar general, and Father Li the procurator are soon to be removed from us and taken 30 km from Hungtung to the Japanese prison at Linfen. It is supposed to be a model prison, with a central corridor and cells on each side. The doorways to the cells are very low and can only be passed through on hands and knees. Food is passed through a little window twice a day.

The cells measure 1.5m by 1.8m and are bare apart from a stinking slop bucket. You are four to a cell, and sleep on the ground in the dust and with the vermin. For want of room, the last man in will often have to sleep sitting on the bucket. There is no basin in these terrible cells and to wash minimally a prisoner has to take water from his lukewarm ration when it is ladled out to him at the end of his meal.

However, the little windows are excellent for both observation and communication between the detainees. From time to time there is movement between the cells, and the Chinese are good at relaying messages in their own language, which the Japanese understand poorly.

I am to learn by this means, at the end of March, of the death of Monsignor Tch’eng. A released prisoner brought the news to a Christian and the word-of-mouth Christian-to-Christian telephone reached my cook. Beloved Monsignor Tch’eng had not been able to withstand his terrible treatment in prison for long: diabetes, heart problems and the infestation of horrible vermin in his cell quickly finished him off… We learnt also that he was to be put in a plain deal box and buried to the north of Linfen.

After lengthy confabulation with my colleagues, I decided to go to the Japanese police to ask for the body in order to give it a decent burial. But how was I to tackle this painful subject without arousing the suspicions of the Japanese authorities since we ourselves were not supposed to have any contact with the outside world? I pondered as I followed my soldier escort down the main street. An idea came to me: I would say that I had been followed by a Christian who had surreptitiously whispered the news to me. That was as far as my thinking had got by the time I reached the police officer’s door. He was flanked by his interpreter, a Korean, and by two duty NCO’s. I came straight out with what I had just learned: that Monsignor Tch’eng had died in Linfen prison and I was asking to be allowed to give him a decent burial. The commandant seemed initially to be surprised and not to believe me…an enquiry would be made and I would be informed….

Having been escorted back to the mission I report to my comrades and we wait. The next day we learn to our surprise that a Chinese colleague, Martin Yang, who is a professor at Suanhua grand seminary, has been told of the death and has independently applied to exhume the body and transport it to the Hungtung catholic cemetery. Perplexed, we wait, then a written message arrives from the police station: ‘You are requested to report to the railway station at 1500 hours to take delivery of the body of the spy Pierre Tch’eng’. We are given permission to leave the mission and ask a Christian to help us get to the station. At the appointed hour we see a goods train arrive and there on a flat car, exposed to wind and weather, lies the poor little plain deal coffin which we load onto a cart. Once back in the mission we break the seals on the church door so that we can place his mortal remains there.

Father Yang has joined us and we all get together to organize the ceremony. I propose a simple burial with only male Christians present: the women are still very fearful in the presence of the Japanese and it would be better to keep them out of it. Everyone else agrees with my proposal. However, they express a wish that the body of our bishop might be transferred to a coffin more worthy of his person and his office. It will be difficult but we shall try. In the night I go in secret with another priest to check that the body is really that of Monsignor Tch’eng. I open the box with pincers and, with the aid of a torch, I recognize the bishop’s gentle, peaceful face. Around his neck, tied with a red cord, are the medallions he always used to wear. I place a stole on his chest then I close the pitiful coffin once more.

The following day the funeral ceremony takes place in the cathedral, which has been thoroughly dusted for the occasion. The Christians, men only, are numerous. We emerge from the mass and walk in solemn procession to the Christian village of Suen Chia Yuan, which is half an hour away to the south of the town, on the hill beyond the river. The police commandant and his men escort us, and I have the job of providing a distraction for them at the agreed moment. In effect, when we reach the little church by the cemetery I invite the Japanese to follow me to the presbytery so that I can serve tea to them. Meanwhile the priests celebrate the absolution then set off as if to take the body to the cemetery. But as they pass the orphanage they carry the bier into the courtyard where they finally prepare the body and place it in a magnificent black lacquered wooden coffin given by one of the village notables. Fortunately the cemetery is out of the sight of the Japanese and I manage to distract them by chatting to them. Half an hour later the priests come and tell me quietly that everything has gone according to plan. I learn also that the kind Christians who did the final preparation of the body had found that it had been partly consumed by the lice which had infested his clothing. They had thus dressed him in priestly garments before placing him in the new coffin.

Among the Christians who had assembled for the burial I had spotted Father Han, the man named by Monsignor as vicar general at the start of our imprisonment. Our eyes met but I could show him no other sign of fellow-feeling in front of the Japanese guards. Later he was to succeed Father Kao as prefect apostolic, and then be appointed bishop of Hungtung. He would be consecrated bishop in 1950 by the papal nuncio Monsignor Riberi.

By this time three months had gone by and we were still largely cut off from the outside world. As the only foreigner in a group of Chinese I was permitted to go to the Japanese police station when the need arose. I had thus been able to negotiate, on Christmas eve, the return of the seminarists to their families. In addition to giving me the satisfaction of a first victory this greatly alleviated our feeding problem.

For fun – and to shame the Japanese – I had stopped shaving, and my reddish beard didn’t greatly please them. They tried several times to get me to go to the barber with my police escort, but I had declined on the grounds of having vowed not to shave again for as long as we remained prisoners… Our days were spent praying, chatting, and playing cards or chess. Of course there was no listening to the radio in the circumstances. The odd rumour from the outside world reached us via my cook.

After the troubling interlude of the death of Monsignor Tch’eng our captivity resumed.In vain did I visit the Japanese commandant; I could learn nothing of the reasons for our imprisonment. Finally at the beginning of April 1942, we were told that we were all going to go before a war tribunal! The Japanese were accusing Monsignor Tch’eng of organizing a resistance network; he was the leader; the priests were his lieutenants and the Christians were his footsoldiers…These assertions were not entirely groundless, as Monsignor Tch’eng had encouraged more than one Christian to get to free China and join a resistance group set up by Father Lebbe. But these were one-off events and we, the priests, knew little of such patriotic activities; the Christian laity knew even less…

The Japanese police were unable to present any proof of these subversive activities, and the tribunal confined itself to condemning us to ten days in prison. Since that period had already been exceeded, they let us go against a simple promise that we would serve faithfully the Empire of the Rising Sun – we so promised without any scruples!!

A time of respite

Four months in detention are soon forgotten when there is work to do. But the diocese has lost its leader. Monsignor Tch’eng went to his final resting place in a worthy fashion, with a crowd of Christian men and women as witnesses, and the Japanese knew nothing of it.. His successor is Monsignor Kao, the former vicar general, who was set free at the same time as we were. We must apply ourselves to the task without further delay. That is the order of the day. Each of us goes back to his job and his house.

I return to my presbytery-cavern in town: all the seals affixed to the mission buildings have been removed. I start visiting the Christian groups again; they hasten to make me welcome although spring is not the best of times to visit as these farming families are all busy in the fields and the days are very long. Nonetheless the festivals of Easter, the Ascension and Whitsuntide all furnish occasions for fervent pastoral encounters. I have returned to my bicycle and do these pastoral rounds on it accompanied by my faithful co-worker T’ang Wa, who can be trusted to do all that needs to be done. All the same I judge it prudent to base myself in the town even if the Christian population there is very small. It is clear that the Japanese pay close attention to my comings and goings and keep an eye on my excursions from the town. The fact is that there is no real frontier between occupied China and free China, and it is sorely tempting to head for the latter and there gain greater freedom of action. But I am a pastor and must remain with my flock.

Sometimes a Japanese officer comes to see me. He is very deferential and well educated, which is a contrast with the behaviour of his police compatriots. He likes to talk in English and I suspect that he may be a Christian. One day he invites me to go with him to a tea-house run by Japanese. I hesitate for some time before accepting, fearful that the geisha girls might have other… ambitions. But I do not want to offend him and in the end I do accept his invitation. All goes well, both the tea and the exchange of compliments, all wrapped up in well-known refined oriental politenesses.

Thus the year rolls on, filled with visits to the Christians for whom I am responsible in the villages which surround the town. I meet one thousand two hundred and eighteen of them, according to their details as recorded in my pastoral book.

Passing through the town gates which were guarded by Japanese sentries is not without its comic side: one has to dismount from one’s bicycle, push it forward, remove one’s hat, nod to the sentry and wait for a while. Then, if all is well, one remounts one’s bicycle and disappears into the countryside… Occasionally I am the beneficiary of some special check: the inspection of my baggage or a body search.

Now, from time to time I have money to carry out for my co-workers. This is provincial money, which is forbidden in town but is used in the villages and country areas not occupied by the Japanese. I had to find a way of getting the money through, and this was to attach it tightly to the inside of my upper arm: when they search you, the official begins by running his hands down the length of the outside of your arms, then he makes you raise your arms while he pats the rest of your body. I was lucky and was never caught out, even when the guards went so far as to make me remove the hand grips from my bicycle to check that I was hiding nothing in the handlebars!!

The winter of 1942-3 is long and hard. The Japanese police continue to visit me from time to time. The sound of their boots gets on my nerves but I try not to show it. I am sure they are keeping a close eye on me. One day in March 1943 an officer comes and announces to me that foreigners are to be assembled at Taiyuan, the provincial capital. I try to find out more; he tells me that it is supposed to last… a few days and that it would be better to take a suitcase. I deduce that this will not be just for the week-end! There is no time to lose: we are to leave the day after tomorrow.

I hasten to Monsignor Kao to seek his permission to disappear into the countryside and make my way to free China. Monsignor is perplexed and does not want to disappoint me, but he fears reprisals against the Christians if I disappear like that. He does authorize me to try to escape along the way, but that will prove to be impossible as I shall be escorted by two policemen at all times. These take me to Taiyuan and deposit me at a Japanese hotel. Japanese hotels are truly paper houses and you can hear everything that is going on on all sides. I didn’t understand what my neighbours were saying but there was a good reason for that: the speaking and singing were coming from a group of Dutch Franciscan colleagues who were glad to have met up with one another and were giving little thought to the fate that awaited them. We got to know one another much better during the two day train journey which took us to Weihsien camp in Shantung province.

On the way there our train stops for an hour to take on board a contingent of American and British folk who were to find themselves interned with us. I have the happy surprise of finding in the group six other Belgian colleagues from my missionary society, who are likewise made to board by the police.They are Fathers De Jaegher and Unden, who are working in Ankuo diocese; Keymolen and Wenders, who are professors at Suanhua grand seminary; Gilson, who is the Peking procurator; and finally my very good friend Father Palmers who, as I write, is the last survivor of that group of six.[He died three years later while parish priest at Taipei on the island of Taiwan.]

Weihsien Camp

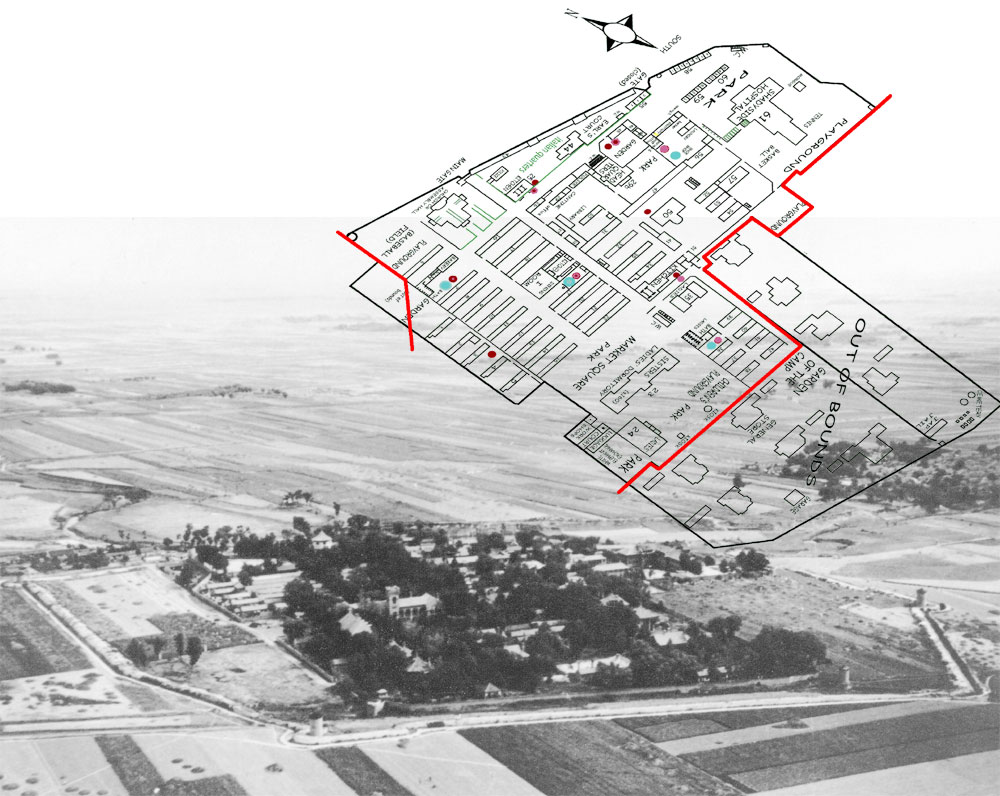

Two thousand internees share what this camp has to offer. It was formerly a presbyterian mission set in the heart of Shantung province. The founder of Time magazine, Henry Luce, was born there into a family of protestant pastors. Our Japanese gaolers have kept the best buildings for themselves and leave us with the student accommodation and with a number of buildings which had been used for teaching.

The terrain surrounding the camp was gently undulating, not to the point where you were prevented from seeing what was going on beyond the perimeter walls, though in order to see over those walls you had to go up the single tower which dominated the center of the camp. Going up there was, naturally, forbidden.

The little student rooms were built on to one another side by side, twelve to fifteen to a block, and formed a succession of rows which were separated by little narrow gardens that were overgrown when we arrived. Groups of blocks could be divided into three or four zones or quarters, each having a kitchen equipped with a simple outside boiler which provided, two or three times a day, hot water for those who wished to make a cup of tea.

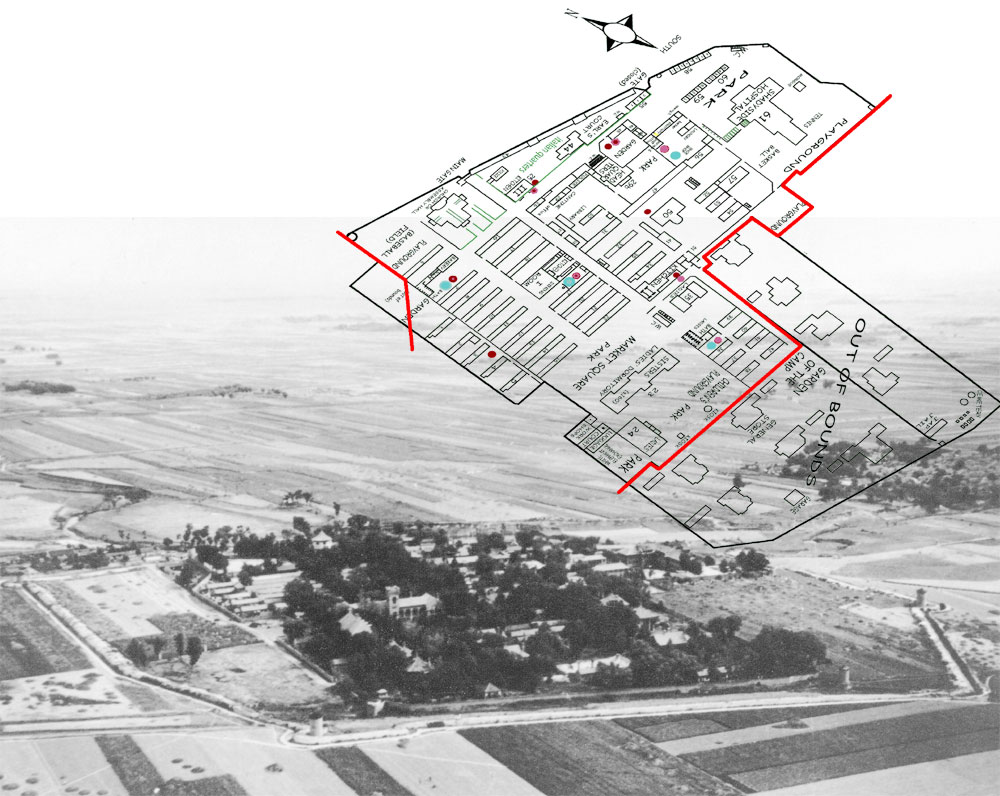

This photo was taken in 1908 by Eric Gustafson's grand father ---

View from Block 23, looking ± North towards block 15 (left) and Block 22 (right)

Market Square in the foreground and Tin-Pan Alley heading to the Church/Assembly Hall.

Our little room stood a somewhat apart. At a pinch you could get four people into its 12 square metres, and that was what we had to do. Four colleagues, fortunately, all from the same missionary society, the Society of Mission Auxiliaries. We share our riches and our poverty… Raymond de Jaegher, who had managed to bring in two wooden chests, let me have them for a bed, while my three comrades had salvaged some iron frames that resembled bed bases. Simple deal pedestal tables served as bedside tables… indeed tables for all purposes. To house everything else a collection of odds and ends of wood somehow turned into a rudimentary set of shelves. In times like those you had to make the best of it!

Improvisation and ingenuity reigned.

Luckily we had none among us who had been convicted of ordinary crimes. We were all deemed to be political prisoners, gathered up and put away because our governments were at war with Japan. Everyone had been living in North China: Peking, Tientsin, Tsingtao or Mongolia. Thirty or so of us Belgians found ourselves in the midst of a host of British and American internees, along with a few Dutch and others. We had become enemies of Japan on the day our own government, exiled in London, decided to open hostilities with Japan to protect the uranium reserves in the Congo which were so coveted by the Americans.

Actually, in March 1943 there were more than a hundred Belgians in the camp. The majority were missionaries working in Mongolia; Scheut Fathers; and Canonesses of Saint Augustine. They left us a few months later, were transferred to Peking and interned there in two convents.

So we ended up as ten or so priests and four nuns available to serve our fellow-prisoners. Initially, life in camp involved a lot of feeling one’s way. How should things be organized? Who was going to teach, cook, mend, build, fix up? Everything had to be sorted out. For example, in No. 1 kitchen where I had volunteered to work our only equipment was six huge cast-iron cauldrons each heated by its own stove. We had to improvise lids using planks and carve great spatulas out of good wood in order to stir the grub as it was cooking…

Very quickly the senior people from Tientsin, Tsingtao and Peking proposed to our guards that we should be left to organize life inside the camp, while they kept an eye on us and stopped us from running away… For our forty guards this proposal had to be a good one. They accepted it and concentrated their energies on guarding the gates and controlling the Chinese who came into the camp to provide various services. They also had to mount a night watch on the seven or eight watchtowers which stood on the perimeter of the camp. Later their task was to become even easier as ditches were dug at the foot of the perimeter wall, to which were added strands of electrified barbed wire.

Life slowly settled down. It was not yet a model community, but all bent themselves to the task of giving it a good foundation. Elections were held to establish committees to deal with various aspects of camp activity: committees for discipline, housing, food, schooling, leisure activities, religious activities, work, and health.

At first each committee comprised three or four people. Later, when camp life settled down to its cruising speed, we were to limit each committee to a single elected person. Every six months we replaced or reelected them. The first discipline committee was chaired by the American Lawless who was impressive and good-humoured. His wife was Swiss and she died in camp. Lawless had been chief of police in the British concession in Tientsin and he took on his task in the camp with competence and authority. Later, when there was an exchange of prisoners, he would be repatriated and replaced by an Englishman called MacLaren, who had a family and had been the Tientsin director of a British shipping company.

As for education, we turned to the teachers. Some of them had arrived in camp with their pupils. It proved to be not too difficult to set up two teaching groups, one each for British and American teaching programmes. There were some two hundred children and adolescents running about the camp and it was pretty urgent to arrange plenty for them to do!

Clandestine Scouts

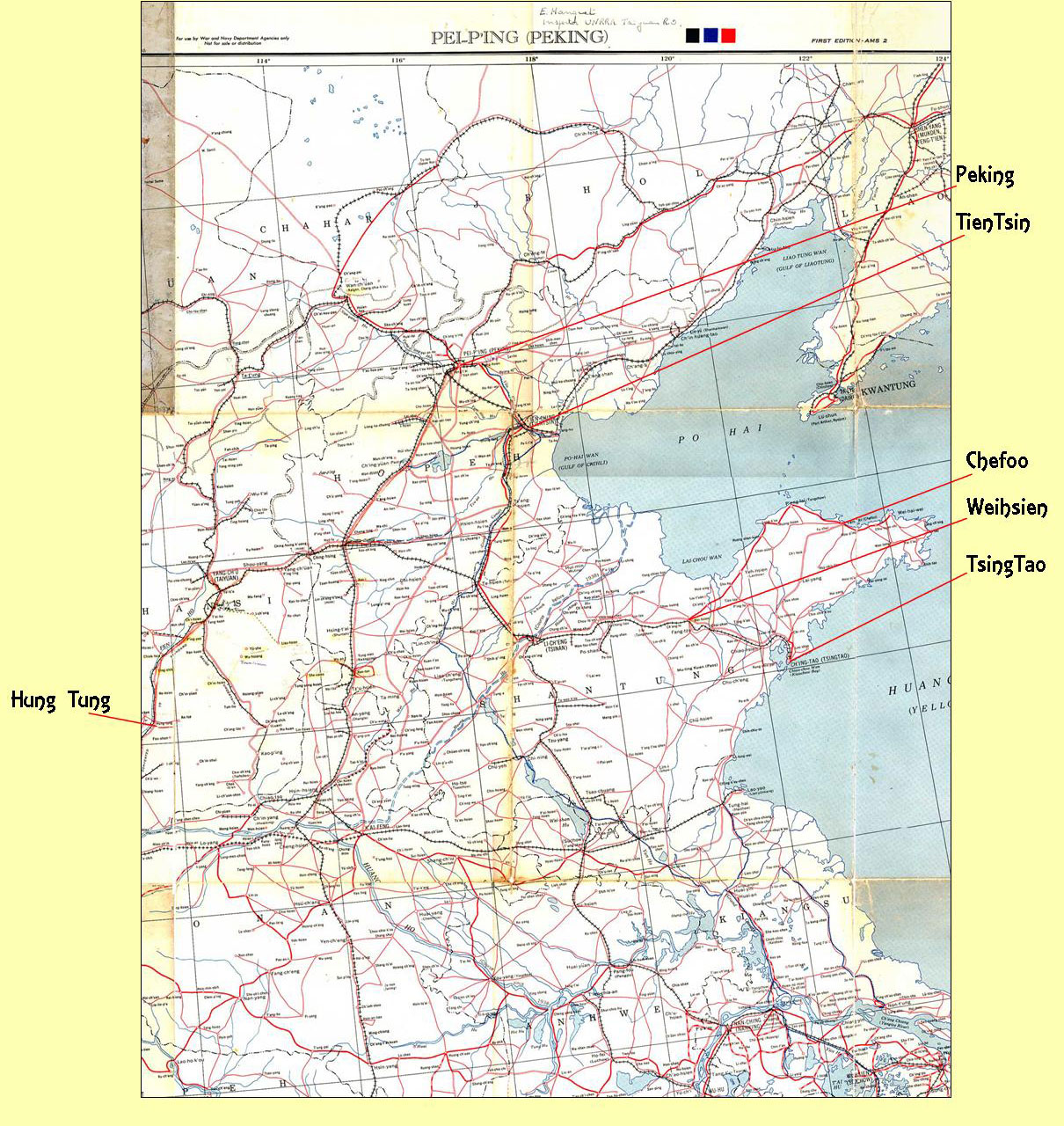

Well now, one Sunday in springtime Father Palmers and I were sitting on a seat by the central alley. The protestant service had just finished and we were chatting with some others from the kitchen and the bakery. Cockburn and MacChesney Clark, both old British teachers, were, like us, regretting the lack of educational activity for the young. All four of us were former scouts and it seemed to us to be a good idea to use scouting methods to bring into being something educational despite the limitations of our imprisonment. We decided to think about it and to ask the opinions of others. Ideas were exchanged, and the contacts developed quickly.

We shouldn’t try to recruit everyone. Let us begin at the beginning! First we needed to establish a nucleus of scouting life, a patrol seven or eight strong. Junior Chan, a 14 year-old Chinese Canadian catholic, could make a good patrol leader; Zandy, a Eurasian; the de Zutter brothers, who were Belgians aged 12 and 14; and finally three or four British lads. There was a good mixture of catholics and protestants, with one orthodox element for good measure. It was decided that Cockburn should be in charge; the rest of us would be assistants.

We have to invent everything and cannot mention scouting as such. The motto is to be All for one and one for all. The badges - a fleur-de-lys on a clover leaf – are to be embroidered by mothers and sisters. The necktie is a white handkerchief dyed in blue ink. Everything else falls into place thanks to scouting skills, and all goes well. When we were liberated we even manage to get ourselves photographed by friends from outside the camp.

Work in the Camp

Everyone had to work in camp. The jobs were organized with a view to the well-being of the two thousand internees, all of them civilians and political prisoners. There were old people and very young children. From the outset a rudimentary hospital was set up to provide basic medical care to those in need. Fortunately it emerged that there were five or six doctors and several nurses among our number. When we got eggs from the Japanese, the whole lot went to the hospital for distribution to the children. The rest of us were just allowed the shells, which went through the mincer and were then consumed as a source of calcium… Actually, our teeth suffered badly from malnutrition, and there was only one dentist for the whole camp. Poor Doctor Prentice spent many hours on the treadle which drove the drill; he filled cavities with dental cement after disinfecting them. That was about all he could do for us…

All available skills were harnessed: carpenter, bricklayer, tinsmith, baker, cook, teacher, seamstress, soap-maker[!], instrumentalist, etc As for me, I offered my services to the kitchen as junior kitchen-hand No. 6. It was a good way of ensuring that you got at least some food! Dare I admit that I hardly lost any weight in camp and that I ended my career in the kitchen as head cook for six hundred souls?! I was proud of my young and active team of six who never complained about the hard graft. My right hand man was one Zimmerman, a Jewish American, who was a far better cook than I was. He had a Russian wife who was a source of good ideas. For example, we were renowned for our Tabasco sauce which was a mixture of raw minced turnip, pili-pili and red peppers which you could sometimes get from the canteen. With these ingredients we would make a sort of sauce that took the skin off your throat but which had the merit of giving some taste to dishes which otherwise had none.

We used to put up our menus when it was our turn to cook - every third day: it was our way of lifting the spirits of the internees. But one day we realized that a Japanese guard would come and conscientiously copy down our menus for sending to… the Geneva Convention! That put an end to our gastro-literary efforts!!

We used to put up our menus when it was our turn to cook - every third day: it was our way of lifting the spirits of the internees. But one day we realized that a Japanese guard would come and conscientiously copy down our menus for sending to… the Geneva Convention! That put an end to our gastro-literary efforts!!

The young people had to work too. Their studies came first. We had organized for them two teaching regimes, American and British. So they went to school every day in the makeshift classrooms. But they were also required to pump water for two hours a day. That was the wearisome task for many of the rest of us too, as there were four water towers in the camp from which water had to be distributed to the kitchens and the showers. Otherwise you got your own water in jugs. The latrines were inevitably very primitive, and had a system of pedals such as used to be found in French railway stations. They were well kept. Oddly enough they were often the responsibility of the Fathers , of us missionaries, although we were few in number! But I have to say that our willingness to undertake this task was not entirely disinterested. The latrines were one of the few places you could meet Chinese, who came to empty them, and we developed good relationship with them with an eye to planning escapes.

To complete the account of the types of work I chose to do or found myself obliged to do during those thirty months I would tell you that I was also a noodle-maker, a woodcutter and, last but not least, a butcher. That was the work I most liked, though you had to be very careful not to get infected fingers. Much of the meat was very poor, but we tried to rescue enough to make so-called hamburgers or stews, though they were mainly of potato. And choosing the job of butcher was also calculated, since there too you could meet Chinese people as they came to deliver their merchandise. Occasionally, and fleetingly, you found yourself alone with one of them and that gave you a chance to exchange news.

That was how I learned of the Japanese military collapse… I hastened to pass on the amazing news to the other prisoners. I remember that some English friends whom I had told of the rumour invited me to take a thimble of alcohol to celebrate the glad tidings. But ‘Beware lest you be wrong’ they said to me ‘for if you are you will have to buy us a whole bottle’. In the event I had no cause to regret my optimism.

Leisure Activities

It is essential to organize leisure activities in a camp if one is to sustain people’s good humour and patience. We would regularly organize baseball matches for American or British teams. The Fathers’ team had a certain notoriety. We were not short of supporters, who were mostly young catholics. Of course were were all pretty young at that time. And music is both soothing and comforting. Thus from time to time there were choral or instrumental concerts. To celebrate Christmas and Easter we even had mixed choirs whose members were committed and which practised hard: these gave much prominence to our catholic liturgies.

The theatre also had its enthusiasts. Even I was sought out one day by an English producer. With many preliminaries I was asked if I would be prepared to take part in Androcles and the Lion , a play by Bernard Shaw. He needed Roman soldiers and he thought that I would fit the bill, being not too skinny! Why not, after all, if that could help to raise the spirits of our community? The tinsmiths busied themselves devising made-to-measure helmet and armour for me out of tin cans that were flattened then pieced together…The play was such a success that we had to stage a revival and put on two performances when the Americans came and liberated the camp. It was our way of saying thank you.

Escaping … from Boredom

But the winters were long and tedious. What do you do in the evenings when you are bored, when you are deprived of liberty? Clearly there was no radio, still less television. That is why a few of us set up a sort of youth club which met three times a week after the evening meal. You could learn to play card games, to hold forth, and even to dance. It was an excellent safety-valve to help young people to avoid descending to more suspect leisure pursuits. Not many people knew that that Father Palmers and I were behind the establishing of a series of evening classes, which were very popular, though they did not appeal to everyone. During the final winter it proved essential to fill every evening…

Escape plans are always a major topic of discussion in a camp. But it was very difficult to escape from our camp. Beyond the perimeter walls and the watchtowers there were deep trenches which had been dug following an early escape attempt; there were also electrified fences which rendered any escape hazardous, especially at night. However, we had established that the electric current was turned off during the daytime. That was a factor that contributed to the successful escape of two of our number, Tipton and Hummel, who managed to take to the fields just before curfew, one fine evening in the summer of 1944.

But that is another story that I shall tell you some other time, as Rudyard Kipling said.

Cesspool Kelly

Old Mr. Kelly was a protestant missionary who had married a Chinese girl late in life; and who had arrived in camp with four young children. He stood out with his dress and his habits for he had gone completely Chinese: clothing, food, speech and way of life.

His children ran about, dressed like Chinese children, accompanied by Dad who couldn’t always keep up with them. One day little Johnny accompanied by his sister Mary ventured close to an open cesspool. [We had no sewers in the camp and the latrines were connected to trenches which were regularly emptied by Chinese coolies.] The predictable happened. Out of curiosity our Johnny went too close and of course fell in. Luckily his sister Mary was on watch. She gave the alarm to passers-by who were able to fish out Johnny before he died of suffocation. As a result of this misadventure he acquired the unusual nickname of Cesspool Kelly .

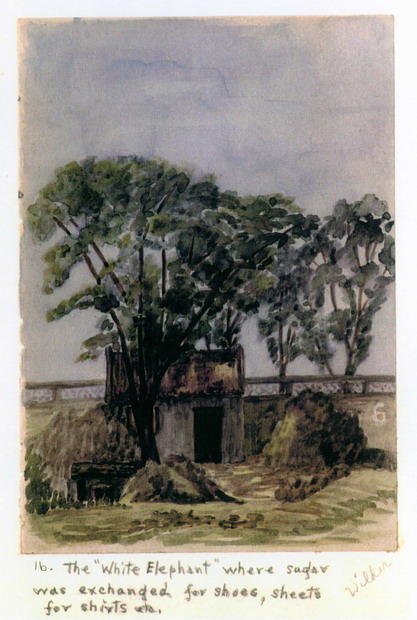

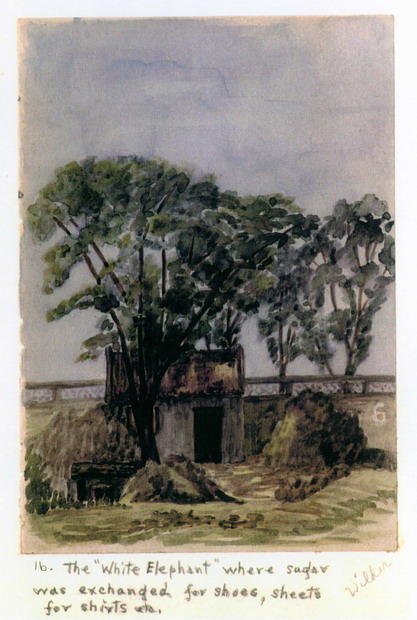

The White Elephant Shop

The needs of everyday camp life made you ingenious and resourceful. Some internees had managed to bring into camp in their baggage more than they needed. Others, in contrast lacked everything. I remember a silver tea service which was sold for a few kilos of sugar to the king of the black market, a certain Goyas, who arrived late in camp but who was preceded by his reputation as a notorious fraudster. Goyas had the tea service melted down into ingots that could be used for currency exchange.

To facilitate exchanges of goods between prisoners the camp committee had the idea of opening a shop where clothes and other items, ticketed with a price, could be exchanged. For example, you could buy some winter garment so long as you brought along another object of the same value, or paid for it with the Japanese yuans which were meted out sparingly to us and referred to as comfort money . This was in the form of a loan which had to be repaid to our governments at the end of the war!

To facilitate exchanges of goods between prisoners the camp committee had the idea of opening a shop where clothes and other items, ticketed with a price, could be exchanged. For example, you could buy some winter garment so long as you brought along another object of the same value, or paid for it with the Japanese yuans which were meted out sparingly to us and referred to as comfort money . This was in the form of a loan which had to be repaid to our governments at the end of the war!

The White Elephant shop ran for about a year, until there was practically nothing left to turn into cash or to exchange.

Cigarettes were another source of currency, at least for the non-smokers. We were entitled to a pack of a hundred cigarettes once a month from the canteen. That was not nearly enough for the serious smokers, but it was handy for those who could use them for barter. The children from Chefoo school – a protestant school which had arrived in camp complete with staff – used them to augment their bread ration, which was never enough to satisfy their hungry young stomachs.

Alyousha’s Fall

He was a young Greek, interned with his family. His sisters, although orthodox, came regularly to our Sunday mass. He was a touch lazy and did not always trouble to fulfil his obligatory work quota. It was necessary to maintain camp discipline and every flagrant breach of the rules was dealt with by our disciplinary committee.

Alyousha’s punishment was to go and collect wood for the kitchen fires. He was as agile as a squirrel, and climbed the trees in the central alley to pull down all the dead wood as an addition to what he had already collected, in order to complete his punishment task. Emboldened by being so at ease, he climbed higher and higher. Holding on to a branch above him, he used all his weight to jump on a dead branch that he was trying to bring down. Fate would have it that just this once it was the branch he was holding on to, that gave way. This all took place near the kitchen and I heard the dull heavy thud of something falling to the ground. We rushed out to see what had happened. Alas, too late. Alyousha lay dead by the branch that he had just brought down…

The Black Market…

In the early days of our internment, the Japanese did little to stop us communicating with the outside world. Apart from the perimeter wall and the barbed wire beyond there were only the watchtowers – or perimeter towers – which occurred on the wall wherever there was a corner. There was however an exception: the camp was not an exact rectangle, and there were blind spots including one section of wall which was hard to see from a watchtower.

The Trappist monks’ accommodation was near to this stretch of wall and Father Scanlon had made it the HQ of the black market, with the wall itself serving as the … counter. The Chinese outside the wall had been quick to take advantage of this feature of the wall to come - by day - and prowl around, offering to sell things, mainly sugar and eggs. At first the orders were delivered over the wall by Chinese who climbed over the barbed wire, but the day came when the wire was electrified and one of the traders was electrocuted and left hanging dead on the barbed wire. The black market was a pretty risky business…

Nevertheless Father Scanlon continued unfazed with his little egg trade and was thus a great help to those families with children. He had found another discreet way to take delivery of his egg orders: a length of guttering which served to carry away rainwater. When the weather was dry the eggs arrived one by one along this guttering, despatched discreetly by a Chinese posted on the other side of the wall.

However, Father Scanlon was being closely watched. Already a guard had once come upon him pacing the wall at nightfall, breviary in hand. He had been challenged: - ‘What are you doing here?’ - ‘As you can see, I am reading my breviary.’ – ‘Impossible, it is far too dark’ retorts the guard. – ‘Yes, but I know it by heart’ replies Father Scanlon.

Alas, what he was up to was stumbled on one day when he was sitting on a stool with his Trappist robes covering the stool below which the eggs were gently rolling out. Up comes a guard. No chance of warning off the Chinese who continues to send along the eggs. One unfortunate egg, more fragile than the others, comes and cracks open against the others. The sound alerts the guard who uncovers the ploy.

Father Scanlon was taken to the cells which were close by the building where the guards lived. The Father, as a good Trappist, was untroubled by solitary confinement and would sing the different hours of the breviary at the top of his voice. This drove the Japanese mad, and after trying him in another cell they decided to send him back to us. That was the end of the black market…

Bed-bugs

When we first arrived in camp the accommodation was clean and the furniture – benches and little tables – seemed new. Those who had brought nothing to sleep on in their baggage had retrieved wooden beds from what had been the school.

Overcrowding and limited washing facilities meant that people and their accommodation could not maintain the highest standards of hygiene. Showers were available to groups of ten at a time and at certain times only. So, after a year of concentration camp existence one began to see discreet first signs of major spring-cleaning.

It was mildly amusing to follow the progress of the problem. At first, the internees would confine themselves to bringing out tables and benches on the pretext that it was a week-end clean-up, and there was the lovely May sunshine… But it was not long before people began to bring out blankets and bed bases and proceeded openly to use boiling water to purge their belongings.

Later we were faced with rats and mice. Competitions were organized and these harnessed the young folk. N. Cliff and D. Vinden became the champion exterminators with a tally of seventy-one.

The Italians arrive

At the beginning of the first winter the Japanese cleared us out of the north end of the camp, to the left of the gate. This part of the camp was then isolated from where we were by walling up two gateways and leaving just one open. For whom were they going to such lengths? Who were we going to be forbidden to meet?

The answer came one evening when about a hundred Italians arrived from Shanghai. They were all senior managers in Italian firms which had continued to prosper in China as long as Mussolini was in power. But after he fell the Japanese, wishing to grab the Italian wealth to be found in the Shanghai concession [banks, shipping companies and assorted factories], found it opportune to imprison these senior staff and their families in our camp while forbidding them any contact with us.

We weren’t going to let this segregation happen. We were all prisoners and were not disposed to favour the burgeoning of divisions in the camp. So, the very first night, we went over the wall to greet the newcomers and to offer our assistance. Among them there were many old people who were confused and distraught. Our youth and our spirit of enterprise went a long way to settling them in. Before long the walled-up gateways were reopened and the Italian prisoners were made welcome by all.

I remember only too well one sleepless night due to Signora Tavella’s coffee. She had wanted to show her gratitude by opening a precious tin of Maxwell House coffee that she had brought in her baggage. We had not tasted coffee since our arrival in camp and were unprepared for its effect. The Tavellas were very influential in their community. After the war we received an official letter from the Italian government thanking us for services rendered to their nationals by the Belgian Fathers of Weihsien camp.

V. E. Day

Thanks to the Chinese coolies who continued to bring in food – and to empty the cesspools – we received from time to time news that we circulated in the form of rumours in order to head off Japanese suspicions. In this way some internees had learned of the Allied victory in Europe and they burned with impatience, wanting to pass on the good news. Two young prisoners dared to break the curfew and decided to go at midnight and ring the bell which was normally used to signal the beginning and end of the daily roll-call.

Action stations for the Japanese! What was happening? Were we being attacked?…Nothing of the kind: just the bold exuberant desire to communicate on the part of two adolescents. They weren’t caught but as a reprisal the whole camp found itself once again having twice-daily roll-calls!

Roll-call Victim

I liked him a lot, Brian, that big sixteen year-old lad, the eldest of four children who had arrived in camp with their mother as part of the Chefoo School group. His father, Mr. Thompson, was in Chungking in charge of a protestant mission and had been separated from his family since Pearl Harbour. Although he was a protestant he had come to me, a catholic missionary, to ask for French lessons. We met twice a week, and thus I got to know him better.

As I said, following the V. E. Day incident the Japanese had doubled the number of roll-calls to one in the morning and another at night. The weather was hot. The young folk, to save their shoes, were going barefoot. It was a general roll-call, which meant that all the prisoners had to assemble in three groups each of about five hundred, be subjected to a precise head-count and, if no-one was missing, wait for the bell to ring before returning to their rooms. Waiting was long and tedious. Sometimes the young folk would pass the time by playing some game.

That day Brian was lined up with his school pals three or four rows behind us. An electric cable ran from the hospital across the open space and hung unluckily low over the groups which had assembled for the roll-call. Someone near to Brian had jumped up, touched the cable, and had an electric shock. ‘Wow,’ said he to Brian. Brian had to try this for himself but, being taller, he seized the cable with his hands and was instantly struck dead. As he fell he pulled down the cable, thereby threatening the lives of other children. Some grown-ups rushed over and released Brian’s grip on the cable with a wooden garden chair. For hours the doctors tried artificial respiration. In vain, alas. He was buried in the camp and his class teacher addressed his classmates saying that Brian had answered the great call…

An Opportunist Postal Worker

My colleague Raymond de Jaegher was a daring and enterprising missionary who spoke and wrote Chinese perfectly. He set much store by keeping his contacts and found trick after trick to get his mail out of the camp without the Japanese finding out. We were entitled to send one 25-word letter a month out of the camp via the Red Cross. And nothing but personal messages. Most of these letters were intercepted and only reached the recipients after the Japanese capitulation.

De Jaegher preferred System D. He had observed that the postman came to the camp once a week by bicycle. He was searched on arrival, as was his letter bag then, accompanied by the guard, he went into the office to deliver the mail, leaving his bike outside. The bike had a cloth pouch attached to the crossbar. De Jaegher unobtrusively slipped into this pouch a packet of letters addressed to the outside world, along with a dollar bill. Then, from a distance, he watched for the postman to leave. The postman collected his bike and found the clandestine package. He looked around and spotted de Jaegher who used his hands to signal thank you, Chinese fashion.

And so, for more than a year he succeeded in dispatching his mail regularly to the outside world, thanks to this ingenious method.

The Seven Warrior Angels who Came from the Skies [17 August 1945]

It is 10 o’clock in the morning. To pass away the time a few people are walking about on the assembly ground which we generously call the sports field. It is the only place in the camp where it is possible to play baseball without running the risk of breaking a window or hurting a passer-by. It is also the place chosen by our gaolers to assemble the internees to reassure themselves that no prisoner has escaped. The weather is marvellously sunny but the temperature is tolerable.

And what was I doing on the sports field where there was no shade at this time of day? I seem to remember that I had noticed the sound of a plane engine, strange and unusual because it sounded different from the engines of the Japanese planes that we were used to hearing. Curiosity had drawn me to the sports field, which was more open and was on one boundary of the camp.

Some in the group on the field with their heads in the air have spotted a red, white and blue roundel painted on the side of the fuselage of the plane which is now flying over us. Speculation is rife: ‘Might it be a French plane?’ ‘What’s it doing in these parts?’ Later we were to learn that American planes have the same colours as French ones. ‘Has it lost its way?’ ‘Is it doing a reconnaissance?’ I should explain that from the air our camp looks like a Chinese village but the Allies were to recognize us because of the coloured shirts that a number of us were wearing. Once the camp has apparently been recognised the plane begins to circle then, above some nearby fields not far from the perimeter wall it releases ten or so parcels dangling from red yellow and green parachutes. What a lovely sight! A few minutes later a second drop releases a further dozen bundles. On the third run we see things that look like sacks of potatoes appear, then these suddenly acquire arms and legs and above them we see big white parachutes opening. There are seven of them. What should we do?

Out of the Camp

Despite the expressionless faces of our gaolers a rumour had been going round the camp that the Japs had been having some setbacks. We knew nothing of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki which had brought Japan to sign a document of unconditional surrender on the15th of August 1945. I had tried to find out more from some Chinese who had delivered a cartload of vegetables to us. Taking advantage of one opportune moment I had gleaned in confidence that the Japanese were abandoning the nearby town. I had spread this long hoped-for news throughout the camp.But only on that marvellous morning of the 17th of June did this great hope seem to become a reality…

Now, while one of our comrades, strong and bold, had hitched himself up onto the boundary wall to see just where the parachutes had fallen, the rest of us had, as one, rushed towards the gate to the outside which was guarded by two sentries. There were twenty or thirty of us hurtling down the slope towards it. Were those Japanese who were on duty going to react? After a few seconds of uncertainty we were out in the countryside running towards those that we supposed, and hoped, were our liberators.

In the midst of tall heads of maize, standing on the tomb of a Chinese notable, an American major was giving orders. He seemed to us to be the liberating angel in person. What a welcome. We looked around for his companions. ‘There are seven of us,’ he said, ‘and we have twenty bundles to gather up as well as the parachutes. To work, now!’ It took barely an hour to assemble the team and the materiel. One member of the commando, a 17 year-old Chinese, a volunteer interpreter, making his first jump, had broken his foot on landing.

We returned to the camp in triumph bearing them all on our shoulders. We were wild with joy. However, the major calmed us down and advised us to let him go ahead with his men, each armed with a bren gun and with revolvers in their belts. They could reasonably fear a violent reaction from our guards. Nothing of the sort, happily.

The Japanese commandant had assembled all the guards and was impassively waiting for the parachutists to arrive. He knew full well that the war was over…Two interpreters, British Eurasians who had been interned with us, were present. The exchange between the Americans and Japanese passed off smoothly. Orders from on high confined our former gaolers to their accommodation while entrusting to them the guarding of the camp at nighttime. We learned that a guerilla force of communists were heading for the camp hoping to take us hostage.

A Well-Organised Rescue Operation!

Despite our hungry curiosity to know everything, our rescuers were too busy that day to tell us about the operation that had been devised to rescue us. But the following day we got to know the details: they were all volunteers for the mission, and had been brought together just twenty-four hours beforehand in order to get acquainted with one another and to clarify individual tasks. When told of the risks they were likely to run, none of them had backed out.

The team consisted of a major in his thirties, the leader of the mission; a captain; two other officers - one for liaison and one a radio specialist; an orderly; a Nisei [an American of Japanese origin]; and a young Chinese who would act as interpreter if needed. They had come from Kungming, an American base in Yunnan province in South China, and had flown for six hours to reach Shantung province and begin the search for our camp. After dropping them the plane had continued northwards to a base which had recently been liberated and which was not so far to fly. In the following days other packs arrived from the sky containing clothes, food and shoes. One of these drops included an unusual delivery and this bears recounting here.

A flying fortress released over the camp a multitude of brown paper butterflies on which was written something to this effect: ‘Prisoners of War! The American government has decided to take care of you! Here is the menu for your next meal: Tomato soup; Tinned ham and Princess beans; Peach Melba for dessert.’ Since these wondrous things did not seem to follow from the sky, this seemed to us to be inappropriate. Or was it just black humour?

Whatever it was, at the request of the authorities we put down white strips as markers around some of the nearby fields to show where the drops should be made. We had little experience of such matters, but then neither had the pilots of the flying fortresses who were better trained in dropping bombs than food! We then waited lined up like good boys along the marker strips! You could hear the roar of these huge planes long before they arrived. At the right moment the holds opened and out of these gaping bellies came metal canisters filled with tinned food, hanging in bunches from the parachutes. Were these canisters too heavy, or were the straps not fixed properly? In any case, some of them came away from the parachutes, hurtled down, and hit the ground close to us just like real bombs. As they landed the bottoms burst and we were spattered with peach Melba or toothpaste!

It was miraculous in every sense of the term, for no-one was hurt – even more miraculous as many Chinese had joined the curious onlookers. Two or three of these surprise parcels crashed inside the camp near the hospital and one or two dumbfounded patients were to see tins of apricots and apples bowling towards them at high speed!

Readjustment…

Among other things our liberators felt they needed to reorientate our minds. They feared that Japanese propaganda might have played havoc with our enfeebled brains which in any case knew nothing of the tragic events of the conflict. Thus we were required to attend sessions in which we were told about the sequence of events in the Pacific war and its litany of atrocities, ending with the final apocalyptic bombing of Japan which had resulted in the capitulation of the Empire of the Rising Sun. And we knew nothing about the atomic bomb!

Loud-speakers had been set up all around the camp and these put out music all day long. Every morning at 7 a.m. we were awakened by the strains of:

Oh what a beautiful morning,

Oh what a beautiful day.

I’ve got a wonderful feeling,

Everything’s going my way…

It was not long before we had had enough of being dragged out of our sleep so very bright and early. The more so as one fine morning an absent-minded liberator put the record on at 6 a.m!

The captain charged with our reeducation was somewhat lacking in humour. During one evening’s entertainment with a group of young folk who were used to putting on campfire sketches we gently depicted him as a donkey: he took the point….

During this period, the intelligence staff continued its work. Each ex-prisoner had to be interviewed by the G2 staff. You had to answer a whole series of questions before being passed fit for repatriation. No-one escaped from this interrogation. Some of us were worked over more thoroughly than the others because of their antisocial behaviour or because their attitude to our guards was too friendly…

Such slowness and shilly-shallying seemed to us hardly necessary and was delaying our getting back to work from which we had already been missing for a good thirty months. The young especially were chafing at the bit. Two of them, who couldn’t take any more of it, had stealthily left camp and were following the railway line to get to Tsingtao on foot, a distance of some 100 km. They were caught three kilometres down the line and brought back to camp, sheepish and discomfited.

Finally, towards the end of September, a first contingent was evacuated by lorry to Tsingtao. As for us, we had to mark time until the 17th of October 1945, when we left camp in a lorry which took us to the airfield. There a Douglas DC 47, fitted with sideways-on metal seats, took us to Peking, fifty at a time. This was the only way to empty the camp: the railway and the roads were blocked or cut by the communist army.

A civil war was beginning ...

#

This photo was taken in 1908 by Eric Gustafson's grand father ---

View from Block 23, looking ± North towards block 15 (left) and Block 22 (right)

Market Square in the foreground and Tin-Pan Alley heading to the Church/Assembly Hall.