... first letter home

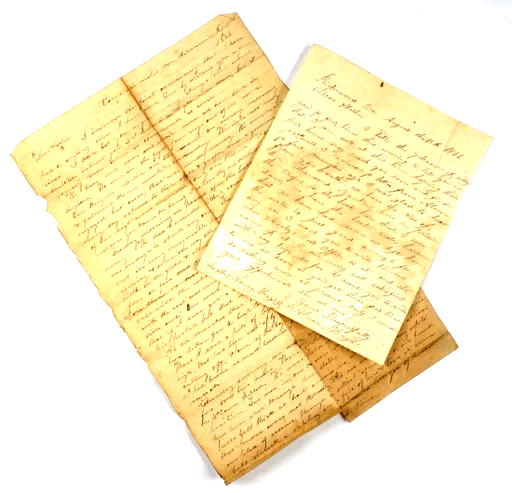

This is the very first UNCENSORED letter on Red Cross letterhead written by Mr. L. Pander Sr.

... to reassure his family in Europe.

It is certain: EVERYONE suffered from this stupid war — … (!).

Dad’s letter is above all reassuring.

There is no longer any censorship, of course, but “we” remain cautious!

Letter written on “American Red Cross” letterhead:

Tientsin, October 21, 1945

Dear All,

You can imagine how happy we were to finally hear from you. Your letter of September 23 reached us yesterday: it was short and we would have liked more details. Perhaps your next one will be less influenced by Z―’s desire not to displease the censorship.

The latter, if not thoroughly abolished, has become much more tolerant. Enjoy and tell us everything!

We too if we were together would have things to tell you, but by letter really, I don’t know where to start!

We learned in camp of the surrender of Japan on August 15; we weren’t expecting it and personally I thought we would have another rough winter to endure!

Two days later, on the morning of the 17th, seven American officers landed near our camp by parachute and I can guarantee you that the internees gave them an ovation which they will remember for a long time. They brought food and clothing and since then we have been literally bombarded by packages falling from the sky and dropped by parachutes by fortress planes from the Pacific Islands. We lacked nothing, I assure you; we were even too spoiled.

Unfortunately, the evacuation of Weihsien involved very difficult problems.

The region was infested with Chinese troops who disagreed with the central government and who amused themselves, I don’t yet understand exactly why, almost daily, destroying the railway lines towards the coast and towards the North. Only the way of the air remained free and it is that option which the American authorities finally adopted. So, we returned to Tientsin on October 18 by plane. Quick and wonderful trip and an unforgettable experience for the kids who all three suffered from airsickness!

And we found Tientsin swarming with American troops; the Bank and our apartments in a chaotic state and still officially occupied by the Japs. We will have to wait a week or two before we can return to our “home”!

In the meantime, we are staying with French friends who have given us a very warm welcome. However, we are still very confused and I believe that it will only be in one or two months that we will be able to resume a more or less normal life.

We would like you to see the children, they are wonderfully healthy. Janette is seven years old, tall and pretty, very nervous and very sensitive, very intelligent too; she asks to go to school because she likes to read, write and count. She speaks English perfectly.

Leopold is a burly brigand who thinks only of shouting, playing, breaking, fighting; he is spoiled by everyone because he is a handsome kid and I believe he will become difficult and complicated. Perhaps discipline will have more effect on him here than in Weihsien; I hope. Marie-Louise is the model for babies: healthy, tall, fat, cheerful, not capricious, she was walking at 13 ½ months and never gave us the slightest trouble. As soon as I can, I’ll take some photos that will hopefully show that we have every right to be proud of our three brats!

Write to us, until further instructions, via our embassy in Chungking, by plane and if possible, through the American Red Cross.

Be well, take care of yourself and Clava, the children and I love you all with all our hearts.

Paul

Tientsin, January 8, 1946

Dear All,

[… family gossip …]

(...) Despite the Japanese occupation of China, we ― like all foreigners ― lived freely in Tientsin before December 8, 1941, though singularly poisoned by a multitude of restrictions the Nips imposed on business, communications, movement, etc. but we bothered very little about them, and we lived as we liked, that is to say very comfortably!

Everything changed on December 8, 1941, the day when, around 8.30 a.m., the headquarters of the Bank were invaded by the soldiers who kept Pétiaux and me in sight, insisting that I give them the keys to the safes and vaults, which, after my refusal, I was obliged to do at about one o’clock in the afternoon, in the presence of our Consul, whom the Japs had brought, and the director of a Japanese bank who was, so he said, instructed by the authorities to “liquidate” the Belgian Bank!

I grumbled like hell, arguing that Belgium had not declared war on Japan, that the Bank was private property which they had no right to touch and — finally, after several days of unpleasant discussions, they authorised the Bank to reopen on December 15th.

This did not last long, for on the 20th, our government in London having officially declared a state of war with Japan, the Bank was re-invaded on Monday, 22nd December 1941, this time without further hope.

We were thus, under the leadership of Japanese “experts” for the liquidation of the Bank!

We have, of course, skilfully cheated them and so thoroughly ― they are so stupid ― fortunately for us, because they didn’t even notice!

Despite their arrogance, they left us quite alone. They took our radios and our cars from us, they reduced our salary to the level of a Chinese employee, they forced us to wear a red armband, but we were authorised to continue to live in the Bank’s apartments. We were also able to go out, to walk around in a fairly large area. The entries of the Bank were, furthermore, barricaded and guarded by troops.

And so it was, with relatively little trouble, that we lived until the end of 1942, when they threw us, purely and simply, out of our apartments.

The two families settled together in a fairly comfortable house, located apart, far enough from the centre where we hoped that we would be forgotten and that we would be left alone.

Alas! around mid-March 1943, we were invited, along with about thirty other Belgians, the majority of the other persons being British, American and Dutch, to be ready to go to Weihsien! ― another location somewhere in China.

We could only take a limited amount of luggage; our furniture, piano, etc. ― our magnificent carpets had to be abandoned in our locked accommodation, the latter having to be handed over to the authorities and ― you can imagine the rest!

The bandits!

And on March 29 (1943) at 8 o’clock in the evening, we were, all under guard, herded on foot from an assembly point in the city, to the station.

You can’t imagine what this 24-hour trip was like, packed, 120 of us, in a 3rd class wagon, doors and windows closed and closely watched by so-called “consular police guards” who were arrogant, surly and only looking for an incident ― to have the opportunity and satisfaction to show their strength!

Everything went relatively well, however, until our arrival in Weihsien where our first impressions resulted in deep discouragement and a monstruous blues!

Imagine an enclosure of about 300 by 250 metres, a few large buildings and about fifty rows of low houses ― “blocks” as we called them later ― each made up of about ten “chambers”.

This enclosure, before the war, was a Chinese school run by the Protestant Missions and these “rooms” served as accommodation for the Chinese student residents. It was we who replaced them and we were lucky enough to be designated, as soon as we arrived, for a well-located “block” where we were allocated, for the four of us, two of these small rooms. Each was 9 feet by 12 and 10 feet high, one window looking southwards about 3 feet by 3 and another to the north about 3 feet by 1.

When we arrived these rooms were completely empty and despite the promise made by the Japs to deliver our luggage to us immediately, they made us wait ten days during which we lived really rough, without beds, without blankets, so to speak without crockery and that was not being that thanks to the help of some missionaries and some friends that we were able to put a mattress on the ground and that we were able to eat in bowls!

There was obviously no organisation and it was us, the internees, who from the beginning had to install kitchens, bakery, toilets, showers, hospital, offices and ― all this infrastructure in dirty and dilapidated premises and with a makeshift equipment.

Fortunately, we had up-to-date men; for example, all the best doctors in northern China, engineers, workers of all kinds, willing and competent.

The beginnings were very hard, but the Japs left us fairly quiet by declaring that they were there to keep us locked within and not to take care of our comfort, our health, the preparation of our food, etc.

The camp appointed a committee which to the end succeeded in keeping ― thanks to its always energetic attitude ― a prestige which was on several occasions very useful to us and which saved us from the atrocities caused by our gaolers, or applied the necessary disciplinary measures which the Japs would have wanted.

This Committee, once constituted and efficient, negotiated certain thefts to their outcome, supervised the escape of two internees, controlled pro-Allied demonstrations or demonstrations against the reduction of rations, etc. etc.

I was part of this committee and I assure you that it was not always easy to navigate between the 1,500 internees and the Japanese Commander of the camp and especially his police chief, a former gendarme with a repulsive physique and a brutality worthy of his race; we even nicknamed him King Kong!

However, we were always privileged: we rarely ran out of food and our friends from Tientsin often sent us packages. Throughout our stay in the camp, we always had bread, most of the time excellent, made by about thirty internees led by two or three professional master bakers.

The camp had organised a special kitchen for kids under five; they were given the best cuts of meat, the best vegetables, they were given milk - obviously a little - and an egg a day and all this was prepared by a few ladies, under the supervision of dietitians. In addition, all the children at Weihsien looked radiant.

As for the adults, they had to work hard, first for the community and then for themselves! And you can trust me that on this regime, we did not get fat!

But that is all over now, and we are not going to complain about it!

Others, by the thousands ― in other camps worldwide — suffered much more than we did and if we sometimes grumbled about the degrading work that had to be done, about the length of the war and the absence of news, we realised that we were highly privileged prisoners in Weihsien!

January 12 (1946)

I just reviewed what I typed in the last two or three days: it’s a bit confusing, a bit far-fetched, but it may give you an idea of what our life had been like in recent years. I will no doubt have the opportunity to tell you a few more stories from the camp; you must think that in our little village of 1,500 souls there was a lot of gossip and that we sometimes had fun with little nothings which, however, helped us for a few hours to cheer us up and find the life not so stupid!

[… family gossip …]

See you soon ― more news, I hope I will also receive yours and I hug you all with all my heart.

Paul