When I was a teenager and, like most girls, very romantic, my mum told me how she and my dad got to know each other. Mum ― Inger ― was 21 years old when she started at Bible school course in Oslo. That day, she arrived a little after the course had started, so she ended up at the back of the class. Then one day just after she had arrived, she felt a handful of snow being pushed down her neck. The person who had pulled this prank was, of course, Gerhard.

As far as I know, this was "the sweetness of the first meeting".

What did we say as children when the boys threw snowballs?

"Love begins with throwing and ends with washing nappies."

Who was your mum?

Her name was Inger Wilhelmine Jørgensen ― born in Drammen on 27 August 1911. Her father, my grandfather, was employed by the customs service. So there was a lot of moving around as he rose through the ranks. They lived in Tønsberg, which was my grandfather's birthplace.

Aunt Aase (on the left)

and mother Inger together

with my grandparents,

Frieda and Carl Gustav

Jorgensen.

Later they travelled to Risør, Arendal and finally Grimstad.

Here they settled and stayed until they died.

Father Gerhard (no. 2 from the right at the back) became the big brother of a large

group of siblings and grew up in Haugesund.

At that time, when my mum was young, it was not so common for young girls to get an education. On the other hand, it was important to be able to look after the house and home. So Inger went to Oslo to learn such things. She attended the Norwegian Women's Rights Association's vocational school in housekeeping. After completing housewifery school, she enrolled at the Indre Mission Society's Bible School in Oslo. We are now in 1932. It was here that she met her beloved Gerhard Riginius Danielsen. Two hearts began to beat in sync soon after they met at Bible School.

Father Gerhard was born in Stavanger, but lost his father at an early age. He died of the Spanish flu aged just 27. His mum remarried and moved to Haugesund. Here, Gerhard became a beloved older brother in a large family of siblings.

His father received the call to become a missionary at a young age. He had joined a revival in Karmøy. He then tried to get into the Missionary School in Stavanger. But they didn't accept students every year, so he had to wait. He didn't have time for that, so he decided that he could take a couple of courses at the Bible School in Oslo, and then he wanted to go travelling.

Thus began the planning of a future together.

Mum trained as a nurse at Ullevål Hospital between 1933 and 1936, and Dad trained as a medic at the military hospital in Oslo. It was Albert Lunde's congregation in Oslo that was willing to send the two young people out through the Norwegian China Mission. While abroad, they would be regarded as emissaries for Hudson Taylor's old organisation: the China Inland Mission (CIM). Later, they signed up as missionaries for a new organisation.

Later, they signed up as missionaries for a Norwegian church in America.

Learning English was part of the job for future missionaries. So Inger and Gerhard travelled to England to study the language.

Now you would think that they were ready to travel to the mission field together. But it wasn't that simple. The rules were such that the man had to travel out first to study the Chinese language. To give him time to do this, his fiancée could not leave until a year later.

It was certainly a difficult year for the two young people. Perhaps it was particularly difficult for her, as her fiancé was in a country ravaged by civil war, making it difficult to send mail.

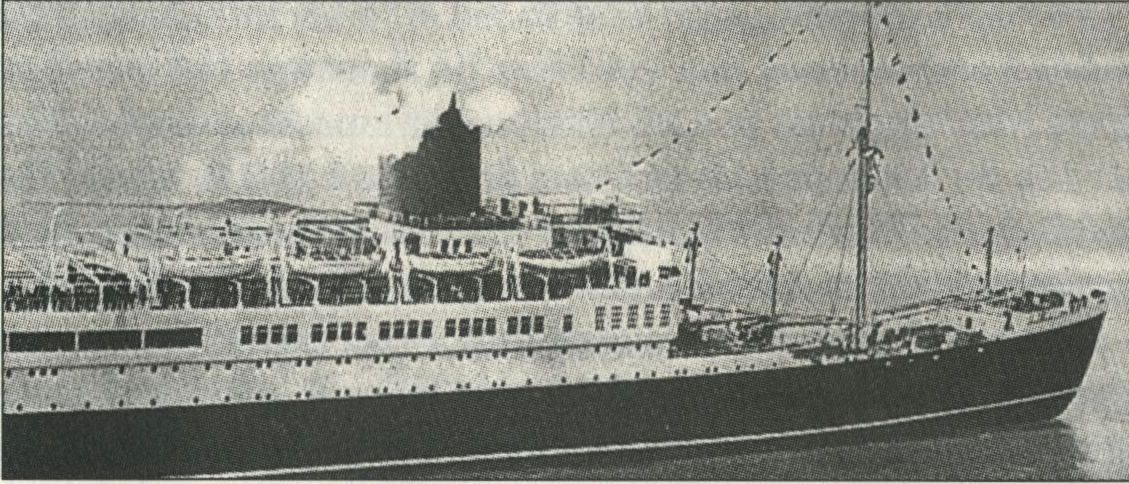

When the compulsory year was over, it was finally mum's turn to travel. She travelled on the ship Scharnhorst from Hamburg.

Mother traveled out to China on the German steamship Scharnhorst.

On board were several well-known people, including missionary Peter Torjesen with his wife Valborg and family, who had been in Norway on holiday. Torjesen, who was originally from Kristiansand, had taken it upon himself to look after mum and get her safely to where she was going. I know he took the task seriously, and they arrived in Kikunshan safe and sound.

Mother and father as newly engaged

in Norway.

We have now in April-May 1938. At this time, my father was far north in China. I let missionary Georg Rinvold tell the story as he has done in his book "Missionary in wartime China".

"- Missionary Danielsen, saved my life! Save me! The cry of distress came from one of the members of the congregation in a long column of Chinese prisoners. They were being driven through the village by a Japanese officer with a raised revolver.

Missionary Gerhard Danielsen from Haugesund stood outside the chapel with a number of Christian Chinese friends and watched what was happening. Some of the Japanese military forces that had reoccupied the city were in the process of moving soldiers northwards along the Yellow River. A labour column of Chinese prisoners passed by. They were forced to carry the Japanese ammunition and equipment. They probably didn't expect to get out alive. So he shouted at the top of his lungs, the Chinese Christian in the middle of the crowd of prisoners: - "Save my life, missionary Danielsen, save me!

Danielsen reacted spontaneously. He ran down the stairs, not recognising the officer with the raised revolver, he simply grabbed the Christian prisoner and tore him out of the ranks.

At the same time, he told the Japanese officer what he thought of the Japanese ravages.

The officer did nothing. He was so surprised that he forgot to use his firearm, and the column just continued on through the city."

Georg Rinvold says that my father Gerhard Danielsen was a brand new missionary colleague at the time. The young Gerhard had come to the mission station to learn Chinese before he started working as a missionary in earnest. As soon as he arrived, he proved to be an unusually brave person, and after a few days with the Rinvold family, he was placed at the mission station in Fuku, on the other side of the Yellow River. The intention was that he should not succumb to the temptation to speak anything other than Chinese.

While he was there, the Japanese continued to take Chinese prisoners forcing them to carry equipment along the Yellow River.

It rained a lot those days, and the steep canyon roads were so slippery that the draught animals were unable to get up.

Therefore, the Chinese prisoners were forced to take off their clothes and put them in the mud so that the animals could walk on them in order to avoid slipping.

Gerhard did not have an easy time, because he longed for his beloved Inger. He was afraid that the war situation might be such that they would end up on opposite sides of the front, or that Inger might end up in Japanese captivity.

He therefore wanted to travel south on the other side of the Yellow River and reach Inger that way. But Rinvold advised him not to do this. In that case, he would first have to get permission from the board. However, Gerhard was so worried about how Inger was doing that he travelled anyway.

Then they got married and returned as husband and wife. This happened in May June 1938. My father kept a diary from this time, and it is interesting to read his descriptions of the "hardships one has to go through to get married!"

-

Mother Inger and father Gerhard —

bride and groom in China.

Invitation to a wedding in Hankow, China.

Somewhat humorously, he writes the following in a Preface:

"It is true that 'books are the best Christmas present', and as we cannot send you anything else from the wilderness here, we thought a little reading material would not be to be despised. This is the first edition of the book, which will probably not be published in several editions and will therefore be a very valuable document for posterity!

Some of the content will probably be familiar to many readers. But it is impossible to give a complete account without repeating this."

He apologises that he could probably have written more extensively about some things. But he wrote most of it after exhausting days, and that's when you're most likely to sleep, even if it's only on a kàng.

My father was happy to explain what a kàng was: "In any Chinese home, along a wall you will find a wide platform, about 75cm from the floor. This is the kàng, a hollow structure containing a chimney, heated by the smoke and hot air from the kitchen fire. It serves as a table during the day and a bed at night. It is built of stone and earth.

My father ended the preface by writing: "Sent out with the author's heartfelt wish that it may give the reader an enjoyable time and perhaps a good laugh. And that the reader could get a small impression of a missionary's travelling life in China.

If this happens, then the purpose of the book was achieved."

He then begins his account of the journey to fetch his bride:

"As I write this, I am in one of China's famous summer resorts, enjoying the peace despite the turmoil around me. About two months ago, I came here to Central China from the far north. Since I got here, we have celebrated a wedding, and we are now having a wonderful time here in the mountains. But to get down here I had to travel about 300 Norwegian miles - half of the way on muleback and with military trucks.

China stretches for about 3,250 miles (5,250 km) from east to west and 3,400 miles (5,500 km) from north to south.

On 23 April I travelled from Paoteh across the river to Fuku.

Some preparations had to be made here. I ordered riding animals and sent a telegram so that I wouldn't be too surprised. The next day we set off.

My travelling companion included some people from the authorities, so half the city council and other leading men accompanied us out of town. Looking ahead, I wondered what would happen on the way. Everything is so uncertain in these times.

But I had good courage and was prepared for a bit of everything.

After I had ridden a couple of Norwegian kilometres, the hardships began. We rode on mules, a mixture of horse and donkey. These animals can carry all the luggage on their backs, and to top it all off, you sit with your feet on either side of the horse's neck.

We were now climbing up the mountainside. As we got higher, it became more and more dangerous. The road was right on the edge of a cliff several hundred feet high. A single misstep by the animal and we were no more. It could be quite nerve-wracking. But the animal walked as if on the living room floor, it was so used to this.

We arrived at our watering hole around six o'clock. It was outside a town with high walls. I spoke to several people and asked if they had heard the gospel, heard about Jesus. But they shook their heads, they didn't understand who I was talking about.

As I walked around the streets of the city and saw the life that people lived there, it was easy to see that this was one of the dark places out here. The place belongs to our field and it became serious for me.

The next day we reached Shen-mu. We had had a long, tiring day and longed to get some rest. But it looked like it would be difficult to get a house, because the town was jam-packed with soldiers on their way to the front. Eventually we got into a private home. It tasted good to get cleaned up. A good meal of Chinese food at a restaurant also tasted good. I think even you at home would have wanted to eat if you had seen me eat.

The next day, one of the drivers came and told us that one of the saddles had been stolen. So we couldn't go any further that day. But we had to move on, and after much haggling we got hold of a new saddle.

This delayed us a lot, and we had to push harder than usual to find a place to stay.

We were now travelling through desert areas. There were no houses anywhere. One has to take in houses for the night. In such places there is also no place to eat, so poor whoever doesn't have a little in their pocket!

This was my first time travelling in a sandy desert. I found it exciting at first, but it didn't last long.

We passed large caravans on the way. There could be over 150 camels in each one. They were all used by the military to transport ammunition and weapons.

We had three days in the desert behind us when we got to feel what a sandstorm is. The wind started to blow when we went out in the morning. It increased until it was impossible to see the head of the horse that was only two feet in front. It whipped and stung worse than hail. Although I had tied my handkerchief in front of my mouth and nose, my mouth was full of sand. I had big glasses for my eyes, so they were well protected. The worst part was finding the road, because it was completely blown up. We were heading south. Then we would get to people even if we got lost.

To the north there's nothing but desert, and we could walk for days without finding people. To the south we would spend two days at most. But we did reach our destination, Yulinfu.

This is the capital of North Shensi and quite a big city. Now it was especially crowded because of all the refugees. There were a lot of big schools here. I was able to visit an industrial school because one of the teachers was a believer. The missionary work here is run by Swedes. Admittedly, there were no foreigners here now. I was allowed to stay at the mission station, where the evangelist looked after the work. I went with him to visit some of the believers, and it was good to meet them. For three days I had to stop here. But on the fourth day there was a military lorry going to Sian. I got a ride on it.

Now a new section of the journey begins. It went a little faster with this modern means of transport than with mules. But the roads weren't the best, so the jumps and rattles were worse.

The landscape here was new and interesting. I was also travelling through "Little Russia", which is located in this province.

It was with excitement that I took that itinerary. Not many missionaries have travelled that way. For years, it has been considered the most unsafe up here in the north.

The first night we arrived in the red district. There were strict passport controls and a lot of harassment before we were allowed to enter the city.

We also travelled through Jenan, which is the capital of this little Russia. The people here only live to a small extent in the city itself. They stay in the mountains around the city, where caves have been dug.

On the fifth day after leaving Ylin, we arrived in Sian. From here I was to take the train. But then my patience was put to a severe test. Day after day I walked the long way to the station, about an hour's march. But every time I got the same answer: No train.

Everything was used for troop transport. Finally, after a week of waiting, I was told that a train was leaving. Then it was off.

According to my calculations, I would be there in two days.

But you should never calculate anything in China. We had only travelled to Loyang, about a day's journey, when the train stopped. We waited hour after hour, but it didn't seem to want to go. Finally, when we had been sitting and waiting all day, they came in the evening and threw us out. They said the train was to be used for troop transport. I was accompanied by missionary Riis and his family, and we went to the mission station that CIM had there in the city.

We stayed there for three days.

Time passes terribly late when you want to leave, but finally on 17 May we got a train, and off we went again.

The next stop was Chengchow, where we had to change trains. Here we had to wait all day, because the trains only run at night to Hankow. I left the Riis family at the station while I went to find a hotel. When I came back, I couldn't find them. But immediately an alarm went off, and in one moment the city was empty of people.

I didn't know what to do with myself. So I jumped on a train that immediately started moving.

I had no idea where it was going! But luckily it only went a little way out into the countryside. When the danger over signal went off, it went back.

This town has been terribly bombarded and consists almost entirely of ruins. So I came back and found the others.

At three o'clock in the morning, we headed south through the plains of Honan. We had a couple of alarms on the way, but saw no aeroplanes.

Late in the afternoon the next day I said goodbye to the Riis family, who were travelling on to Hankow.

Now I was going to try out a new means of transport, a sedan chair. It consists of a chair that is carried by four men with the help of two long sticks, which are stuck through, one on each side.

"I was going up a couple of thousand feet. It was slow going, but at least it was going upwards. By seven o'clock I was there.

It was a joyful reunion with Inger after almost two years of separation. I won't attempt to describe that feeling, but leave it to the readers to imagine it for themselves..."

So we leave the two of them alone for a little while; they probably have a lot to say to each other now.

This was from the first part of my father's travel diary. Then the wedding planning began. It was to be a real Norwegian wedding.

According to the sources, the menu consisted of proper sour cream porridge first. This was followed by Norwegian mackerel pies with potatoes and tomatoes, then coffee and Norwegian sandwiches with Norwegian goat's cheese.

The sweets were brought up from Hong Kong.

#

-

-