3. The Second Revolution

I have already stated that after my failure in 1906 as a Naval

Secretary I was for three years left in the trough of the wave

of happenings, though there was always the Marine Department to keep me occupied; but then came the conservancy

consultation at Peking, my visit home, the anti-Manchu

revolution, and from the date of the latter I was again on the

crest of events — in that minor way of mine.

For some years I had seen little of the navy, although owing

to the loss of Weihaiwei, first to the Japanese and later to the

British, it had no home and so had made Shanghai its base with

an Admiralty at Kiangnan Dock — where I had played at being

a Naval Secretary. But now Sah had gone, and Li — my Co-Commander of the Flagship in the war of '94 — reigned in his

stead. When the second revolution came — the one against

Yuan — I wondered why the fleet was left there, as Shanghai

was a centre of Kuomintang activities; and when, on the

17th July 1913, the arsenal was about to be attacked by rebels

having their headquarters in the settlements — they recruited

their forces there, and there too they had signal stations from

which they flashed signals to their front — I began to wonder

more; and, though I was fed up with the navy, I thought I

would go and see what was its situation. The fleet, let it be

explained, was anchored off the arsenal. What I learnt was

serious enough. The day before Li had called a conference of

the Captains; at it two of them had put their Mauser pistols

on the table and declared in favour of revolt, of helping the

forces of the Kuomintang in their attack upon the arsenal.

These two dominated the council; and, as was usual, there was

nothing private at that conference — a fringe of sailors' heads

lined the skylight; and so the crews acclaimed revolt. The

situation looked as bad as it could be — for Yuan Shih-kai.

With the fleet gone over to the rebels they would command the

Yangtsze river and Yuan would lose at least a half of his

advantages. It was a monstrous impending tragedy for China:

so it seemed to me, for like most other foreigners my faith lay

with Yuan Shih-kai; the others were mere impractical visionaries who could only continue a state of chaos.

I asked Li if nothing could be done, and he replied that

nothing could; so it looked quite hopeless. Yet, with no

notion of the use of it, I now asked, 'Would money save the

situation? ' At that Li brightened up and answered, 'Money

would save any situation in China.' Then he went on to

explain about affairs. For two months the fleet had not had its

pay. The men were not like soldiers — mere riff-raff; they

were men with homes, with families and parents to support;

and there was the Kuomintang offering them their pay if

they would take the Southern side. There was no one

except those two Captains with their Mausers who wanted

to rebel; but the belief was growing that the Kuomintang

would win.

'How much money would be needed to meet arrears of pay

and to provide for general maintenance for a month or two? '

'How much money would be needed to meet arrears of pay

and to provide for general maintenance for a month or two? '

— ` About a million taels; but to be of any use it would have

to be got immediately, for the rebels may attack at any moment,

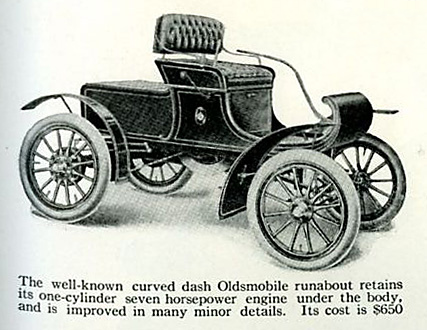

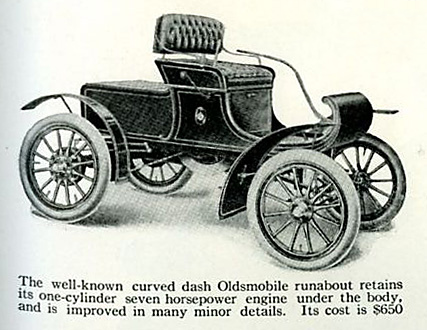

and then my ships will join them.' I drove back the four miles

to the settlement in my Olsmobile — its one cylinder horizontal

and fore and aft — in a thoughtful mood. The Manager of the

Hongkong and Shanghai Bank was A. G. Stephen; and I had

not yet met him. I reached his office at five o'clock and told

him of the situation. The Group Banks held a considerable

reserve of Chinese Government money against its liabilities

for loans, and my idea was that somehow use could be made of

that. But the banks would never hand it over to the Admiral

— it would not be wise to do so. A foreign administrator of

the fund must be appointed; but quite definitely they must

not count on me, for it would be most improper for a

Customs man to so involve himself in party politics. Stephen

said very little, as was his way in business; but he drafted

a cable.

The next morning I again visited the arsenal — the rebel lines

around it had not yet interfered with traffic — to learn more of

what the situation was; and Mr. R. B. Mauchan, the Engineer

Manager of the dock, introduced me to Admiral Tseng, who

was in command of a force of Marines guarding the arsenal.

Tseng was a trusted man of Yuan Shih-kai, and at once I knew

him as a leader — as a real man from a Western point of view.

I told him of what I had done, and he said that if by any chance

the money came before midday on the morrow the situation

might be saved; otherwise the rebellion would succeed,

for he expected the attack to-morrow night. Two years

later Tseng was murdered in the settlement. From the

first we were mutually trusting friends; he was one of

four or five Chinese that I have dealt with, my admiration

and respect for whom was not tinged with a sense of Western

prejudice.

That day H.M.S. Newcastle arrived with Admiral Jerram

and I got a message that he would like to see me. Fulford,

the Consul-General — acting temporarily at Shanghai — came

shortly afterwards, and I told them what the situation was and

what I had done. I made it clear that it was a choice of evils.

It might be a choice between my intervention and Yuan's

downfall; but my intervention would be an evil. In the

position of the Customs Service for one of its employees to

take such a hand in politics had serious disadvantages. Even

what I had done might involve 'my resignation, for it would

inevitably be generally known. The Admiral was encouraging and complimentary. The Consul-General was cold and

unappreciative, and I did not blame him; I did not like the

part I took myself.

I liked the situation even less next morning when Stephen

told me that the Group Banks had placed a quarter million

taels to my credit — with more to follow if I needed it — on

condition that I would administer the fund. I reminded

Stephen of what I had said; he shrugged his shoulders, and I

left him and walked along the river front and tried to get an

inspiration how to act; but it would not come. In a state of

indecision I went back to my office, and there I found a telegram from the Inspectorate — the first of two — which made me

free to act at my discretion.(1)

1 — That telegram was from Mr. C. A. V. Bowra, the Chief Secretary, and

sent, I believe, on his own responsibility, the Inspector-General being absent

at the seaside. It was a considerable responsibility to shoulder.

That altered everything; the main responsibility was no

longer mine; but even so I would not function from the

Coast Inspector's office. I sent my secretary to rent a flat and

hire furniture to serve as a naval office; and then I motored to

the arsenal and saw Tseng and Li. They were to call another

meeting of the Captains — those Mauser pistol men must not

be allowed to dominate it this time — and the news was to be

disseminated among the men. I told them of my simple method

of administration. I would make advances — I gave a cheque at

once — but I would not see a voucher. When the advance was

finished they would provide a summary of expenditure for each

vessel — it included vessels up the Yangtsze — under various

headings: wages, coal and stores, etc. This summary to be

signed by both Li and Tseng; its scrutiny would suffice for

me; it would be for them and not for me to guard against

irregularities. It was arranged that Mr. Chen, Mauchan's

colleague at the dock and an Engineer-Admiral, should be

Paymaster-in-Chief at my new office, and I would function

as the Treasurer. The scheme worked like a clock; there was

never a hitch or a doubt.

That day when Mills, my cartographer, was returning to the

office after lunch, he was stopped by a Chinese in the street

whom he knew to be associated with Sun Yat-sen. 'You are

in Mr. Tyler's office, aren't you? Please tell him that what

he is doing is a very unhealthy occupation.' Sun Yat-sen,

whom I knew personally, lived close to me four miles in the

country. His house had a guard of French municipal policemen; but there was no police for me in the days that followed,

when I had some reason to fear what Sun's emissaries might

do to me and mine.

The attack on the arsenal began on the night of the 22nd

July, so in the saving of the situation there had not been much

margin. It continued every day and chiefly in the night. The

fleet remained quiescent; it was not until the 25th that it was

used against the rebel forces, and then occurred an extraordinary affair. After dinner, from the windows of my house,

we could hear and see the bombardment, and my family

was greatly interested. But soon I realized that shell were

falling round about my neighbourhood, which was nowhere

near the line of fire against the rebels; the settlement was being

deliberately bombarded. I guessed at once that it was one or

both of the ships of those Mauser pistol Captains who did it in

wanton spite, and for the purpose of creating embarrassment

for Li; and I drove in and told the Consul-General, Sir

Everard Fraser, that this outrage was of course not a real

attack, and urged that the difficulties of Li and Tseng should

not be increased by too much notice of the incident.

The attack on the arsenal had its base in the settlements, and

chiefly in the French. In the latter recruiting stations were

undisguisedly established and the settlement authorities did

not interfere. This did not mean that their sympathies were

with the Kuomintang; it was Yuan in whom the Westerners

had faith. The extraordinary situation resulted partly from

inertia but chiefly from that mad obsession of the duty to

render asylum, which has already been referred to.

In the early days of the rebellion I used to report progress

of the fighting by telegram sent through Stephen; they were

addressed 'Tyler to Chinese Government' and ended up

please inform President.'

On the 30th July appears this entry in my diary: The

remarkable affair of the Japanese launch and the torpedo

occurred last night. There appears to be strong evidence of

the complicity of the Japanese navy; but with what object it is

impossible to say.' That is all that was recorded. It referred

to the arrest during the night of a Japanese commercial launch

that was fitted with a spar torpedo rigged and ready for use.

It was not an amateur affair; it was a naval spar torpedo, but

I have no recollection that it was proved to be of Japanese

design. I was just left guessing as to what this thing could

mean. The Japanese Government was opposed to Yuan

Shih-kai. It was opposed to any consolidation of the country,

for that might bring about revenge for '94. It was concerned

with keeping China in a state of turmoil. But even so it seems

hardly credible that that apparently attempted outrage could

have been by order; it is more probable that it was a free-lance

affair. So far as I know no official notice was taken of the

matter.'

1 — I still possess the draft letter to Admiral Nawa — Senior Naval Officer

at the time — on this matter, which, on consideration of its possible results,

I decided should not be sent by Admiral Li. It ran as follows: —

I have the honour to inform you that yesterday the River Police brought

to my vessel a steam launch to the bow of which was fitted a contact torpedo.

This launch was found by the River Police between the Osaka Shosen

Kaisha and the Nisshin Kisen Kaisha wharves, so disposed and with such

fittings on board as obviously to lead to the conclusion that it was intended

to be discharged against one of my vessels.

I have conclusive evidence that the launch was bought a few days ago

by a Japanese from Messrs. Wheelock and Co. In these circumstances I

have the honour to suggest to you the desirableness of arranging for a joint

inquiry into this remarkable occurrence.'

The entrance to Shanghai harbour was guarded by the

well-armed Woosung forts, the garrisons of which with the local

troops in general had gone over to the Kuomintang; and when

the rebellion broke out a squadron in the North — with Admiral

Liu, the Commander-in-Chief — was sent down to capture them

and relieve the arsenal. Liu arrived outside on the 29th July,

and wrote and asked me for advice and help. Would I come

out and take charge of operations against the Woosung forts?

If it had not been for that factor of the reputation of the

Customs Service I might have gone; but positively I drew

the line at belligerent acts.

The relief forces had landed on the Yangtsze bank and

marched overland, and by the 10th August Tseng was ready

to attack the Woosung forts from landward. I had wished Li

to attack from inside the river. There was a berth on which

bore only two six-inch guns. To get there he would have to

run the gauntlet for some minutes — ten perhaps — of the fire

from the bigger guns, but I thought the risk was good enough

and once he had secured that berth he would enfilade the whole

string of batteries. But Li would not do it; and a British

gunnery Lieutenant whose ship was at Shanghai said the

attempt would be very risky; and as it proved there was no

need. The forts were wavering; they had flown a white flag

one day, then hauled it down again. On the 13th Tseng's

troops were advancing across the plain and minor fighting was

going on. Then Mauchan got the news that the forts were

flying the Government ensign as a sign of submission. They

might change their minds again; the thing to do was to arrange

at once for acceptance of capitulation. So Mauchan, Chen,

the Paymaster, and I took a launch to Woosung, above which

Li was anchored, and I tried to persuade him to move down his

ships; but he would not. He said that the Lienshing, a

despatch vessel in the rebels' hands and anchored lower down,

had been fitted with torpedoes. It was therefore decided to

go outside to Admiral Liu and get him to take the necessary

action; but on the way there lay the Lienshing — a small vessel

and unarmed except for a couple of light guns. She looked

quite peaceful; the men on deck also looked quite friendly; so

we boarded and found her officers had left. I was going below

when I felt a sort of warning and desisted, and told the others

not to. A commercial launch was passing up the river, and

we hailed her and arranged that she should take the Lienshing

in tow and deliver her to the arsenal; and so we slipped her

cables and off she went. Let me tell what happened to her.

Either that day or the next a party of naval students visited her

and some went below, and then her after-part blew up; the

deck was ripped right out and a number of the boys were killed.

She had been fitted by the rebels as a booby trap. That

warning proved quite useful.

At the time when we were busy with her, a small gunboat

arrived, sent down by Li but with no orders. And now I was

led into a burlesque escapade of the very kind I wanted to

avoid. To explain this I must explain my relationship with

Mauchan.(1) He was a fiery Scotsman intensely eager in the

Northern cause; prepared to do anything; to run any risks

for its furtherance; he was the sort of man to lead a desperate

enterprise. Now I believed that my comparative inactivity —

my refusal to join Admiral Liu outside and my general cautious

attitude — irritated him; to him I was missing glorious opportunities which he wished he had himself. He did not accuse

me, but I sensed his contemptuous wonder. I think he

believed that my compunctions were but a cloak to my timidity.

1 — I have tried without success to communicate with Mr. Manchan; and

trust that he will not object to what I say about him.

So when with the arrival of the gunboat there was the opportunity to get a guard, and Mauchan said 'I propose we go

ourselves to accept capitulation; are you game to come? ' I

acquiesced, and then entered wholeheartedly into what for me

was a most improper business. We got a landing party of a

dozen men and a Lieutenant, and with them we trotted off

across the country in the appalling heat of August. And now

it was a question of who would get there first, the army or the

navy; and that was why we ran. Yet we could not be sure

that capitulation was really intended; we might well be walking

into a trap, but that was not the case. We won the race; the

Major at the fort was at the gate and welcomed us and took us

in to tea, and as far as I know the word capitulation or the civil

war was never mentioned. Half an hour later Tseng's officers

and men arrived, and then we left.

At the arsenal fighting still went on, and on the 19th August

Tseng said to me: I am in a serious difficulty. Such and

such a regiment has not had last month's pay. It has now

been offered by the Kuomintang, and the officers are considering

the matter. If that regiment goes over it may be the beginning

of a debacle in spite of our success so far. I know your funds

are only for the navy, and I hardly dare to hope that somehow

you could meet my needs.' I thought the matter over. It

would be quite useless to ask permission; I could not get it,

if at all, until too late. Tseng's need was urgent; the purpose

of my fund might be defeated if I did not meet that need; to

do so would involve a misappropriation; but I did not hesitate,

and I gave Tseng a cheque for the equivalent of £10,000. At

the end of the month when I finished with this job, was closing

my accounts and sending in my statements, a very brief reason

was given for this misappropriation. The banks made no

comment; some department in the Ministry of Finance wrote

acrimoniously about it; and from the Minister of Finance,

Liang Shih-yi, I got a complimentary letter conveying the

thanks of the Government for my services.(1)

1 — Acting Minister of Finance, Liang Shih-yi, to Captain Tyler, Coast

Inspector.

'The painstaking and capable way in which the Coast Inspector has

managed the finances since the outbreak of trouble at Shanghai has earned

the gratitude of Foreigners and Chinese alike. The Government have

found him a great support and help. Peace has now been restored and

order is gradually being maintained; the Government recognize the zeal

and ardour shown by the Coast Inspector, and the Acting Minister has

decided to report at once to the President so that he may testify to his

gratitude.'

It had been an interesting job. There is hardly a doubt that

Stephen and I altered history for China, but whether for good

or evil it is impossible to say. His immediate grasp of an

unexpected emergency, the promptness of his action, the silence

with which he did it — he hardly said a word to me — was quite

remarkable. I always regretted that the part he played was not

made public; it was on my account that it could not be.

But it was not a pleasant job. That warning from the

Kuomintang was twice repeated. My diary says: I went

to see Colonel, now General, Bruce, the Captain Superintendent of the Police, about it. His opinion — stated very

emphatically — was that the danger was serious and practically

unguardable against; that the chances for me were short odds.'

It is a disagreeable feeling that a passing car may throw a bomb

into yours; and I did not like it a little bit. For the sake of

my family I got the Government to insure my life, and they

did so for £20,000.

#

'How much money would be needed to meet arrears of pay

and to provide for general maintenance for a month or two? '

'How much money would be needed to meet arrears of pay

and to provide for general maintenance for a month or two? '