- by Pamela Masters, née Simmons

Chapter 8

[excerpts] ...WEIHSIEN PRISON CAMP

I hardly remember the walled city of Weihsien with its massive gates and cobbled streets. It’s all a blur to me.

A stop on the way to a prison camp for the crime of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. We did get one break, though: there were trucks waiting for us at the station—not enough to take us all to the camp at the same time, but still trucks—a blessing, as it was late in the afternoon and a cold rain was falling.

A stop on the way to a prison camp for the crime of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. We did get one break, though: there were trucks waiting for us at the station—not enough to take us all to the camp at the same time, but still trucks—a blessing, as it was late in the afternoon and a cold rain was falling.

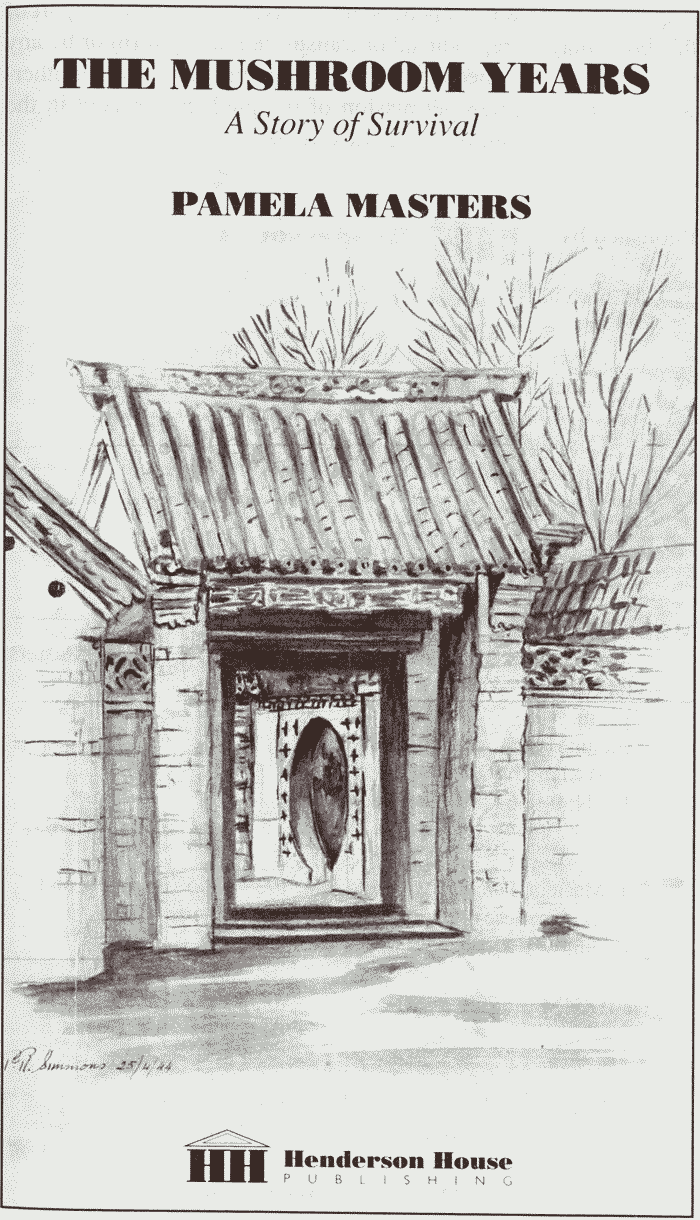

The ride over bleak, rutted country roads was slow and tedious, and several trucks high-centred and had to back up to find surer passage. It took almost an hour to cover the three-mile trip to the camp, and when we arrived, the tired old trucks groaned and skidded as they turned under a huge ceremonial gateway with bold characters inscribed beneath its dripping, ornate grey-tiled roof.

“The Courtyard of the Happy Way,” Dad translated, reading its incongruous message of greeting. “Happy? That’s not what I’m feeling now!” His comment was greeted with several “Amens” from fellow travellers.

Climbing out of the truck, I almost fell, stepping into slick, slimy mud that sucked at my sturdy walking shoes, trying to drag them off my feet. As I steadied myself, grabbing a tarp hook on the side of the truck bed, someone handed down my suitcase and said, “Welcome to Weihsien!”

There wasn’t much to see. Misty rain, dripping trees, rows of soggy grey brick buildings with tiled roofs, and the smell of rotting human excrement. Oh, happy way! Oh, happy day! I thought facetiously, as I found myself being herded along like so many cattle to one of the larger administration buildings.

It was just as well I hadn’t eaten all my sandwich on the train, as we’d no sooner stepped in out of the drizzle than we were told that our first meal would be breakfast the following morning, if volunteers stepped forward to help with the meal. I wonder if Cook ever realized how great the remaining half of that sandwich tasted ...

Somehow we survived that first freezing night. Not surprisingly, accommodations had not been made, so we slept on hard wooden floors, literally collapsing where we stood, curling up in our disheveled clothes, too tired to care. Within minutes, grunts, snorts, snores, and whimpers faded into nothing as we passed out in complete exhaustion.

Breakfast the next day in the steamy community kitchen was skimpy and pretty foul: weak Chinese tea and bread porridge. The latter made with sour bread that had been soaked in boiling water and stirred to a mush, as it was too stale to serve any other way. With no sugar or cream to add to it, it was almost inedible. While we were eating, a committee member came in and told us that, when we were through, we were to go to the athletic field for indoctrination, housing, and work assignments.

The field wasn’t hard to find as it was the only large, treeless area in the camp, and through the years, it was to become the site of most of our outdoor group activities and daily headcounts. Located in the southwest corner of the prison camp, its two six foot-plus exterior walls were of grey brick, topped with several feet of electrified barbed wire. An ugly guard tower with gun slots buttressed the outer corner, and I noted with a chill that there were machine guns mounted in the slots trained directly on us. As I looked up at the forbidding sight, two young guards in black uniforms stepped out of the tower and placed their rifles against the waist-high railing. They looked as though they were in their teens, like me, and as they laughed and joked and punched each other on the shoulder, the incongruity of the situation hit me. Somehow it was hard to think of those kids as my enemy.

Margo came up just then, mad and out of breath. “Where the heck have you been?” she snapped, “You’re supposed to be with us so we can be assigned living quarters. Come on, hurry up!”

I followed her to where Mother, Dad, and Ursula were gathered, and withered slightly under their reproving stares.

As the last stragglers trailed onto the field, there was a loud squawk from a public address system, and the droning buzz of conversation around us stopped. After a few more crackling sounds, a voice called out, “Attention, please! Attention, please! This is your Commandant! Welcome to Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center!”

“Call it anything you want,” Dad said under his breath, “it’s still a prison camp!”

I couldn’t see the Commandant because of the crowds, but I could hear him, and his English was excellent.

“I am a repatriate from the United States,” he went on, “and I was in Hot Springs Assembly Center in Virginia before I was sent back to Japan. I want to tell you something,”—he paused to get our complete attention—”while I was at Hot Springs, I was always treated with courtesy and respect, and I aim to see that you receive nothing less.”

I felt, rather than heard, a murmur of approval run through the crowd.

“But remember...” here he paused once more for effect, “if you want to receive courtesy and respect, you must cooperate. Provocation and disrespect will be treated harshly.

“One more thing. This camp is not Hot Springs. If your rations are short, ours will be too. If you are cold, we will be too. In short, we are all in the same boat; whether we’re all rowing in the same direction remains to be seen.”

He sounded firm, but fair.

Then, he introduced the captain of the guards and interpreted as the stocky officer, with arms well down to his knees, stood stiffly to attention and barked his orders. He also wore a black uniform, and I learned later that it designated that he, like the young guards, was a member of the consular guard and not an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army. I wondered if they would prove to be as obnoxious as their khaki-clad cohorts.

He told us that the arm-bands we had been issued while under house arrest were not valid in camp. We would be assigned new numbers and new tags, which we were to wear at all times, and each morning, there would be a roll-call. Through the years, we were to find ourselves responding with a “Here!” to the guards shout of, “Yon hyaku kyuu juu nana, kyuu juu hachi, kyuu juu kyuu,” Ursula, me, and Margo, reduced to 497, 498 and 499.

Before we left the roll-call field, all the single men and women were told to report to the respective dormitory areas, and heads of each household to the administrative office compound to be assigned cell numbers—only they called them room numbers. Meanwhile, most of the committee responsible for our orderly move to camp pitched in once more to organise work details.

All those not preparing food were to be assigned to cleaning up the camp. The rains of the day before, which had gone on through most of the night, had left the main roadway a quagmire. I found that the stench that had greeted us on our arrival was from overflowing latrines, augmented by piles of soggy garbage in various phases of decomposition.

Somehow I missed the cleanup detail and found myself peeling potatoes with twenty others in the community kitchen—dubbed “Number 2 Kitchen” or “K-2”—where we’d had breakfast a couple of hours earlier. With so many people, and so few potatoes, the job was soon done, and I left the kitchen compound and stepped out onto Main Street, the name some enterprising individual had already posted on the road leading up from the main gates.

The sun had finally come out, and to my surprise, Dad was standing across the street from me in the entrance to a cell compound.

“What’s up?” I asked, as I waved to him.

“Come see our new living quarters,” he said.

I darted around the deeper puddles in the road and stepped through a pretty, little gateway into a long, narrow compound studded with nostalgic acacias.

“We have the first two cells,” Dad said, as he led me to them.

Mother had just completed sweeping out the first one, and she handed the broom to me, saying, “Oh, there you are! Give this to Margo and tell her when she’s through with it to hand it down the line.” Then she turned to Dad and said, “The light doesn’t work. We’ll need a lamp bulb before tonight. See what you can find.. .or swipe.”

I smiled at her remark as I moved on to the second cell, handing Margo the broom as I stepped inside. As she took it and started sweeping, she said,

“For God’s sake, wipe the mud off your shoes before you come in! This is all we’ve got to call home for Lord knows how long—let’s keep it as neat as possible.”

“Where’s Urs?” I asked.

“Rounding up our cots and bedding.”

“And all the good-looking guys in camp!” I said with a laugh, as I turned and saw Ursula coming through the gateway, followed by two good-looking strangers pulling a wobbly handcart loaded with all our worldly possessions.

“Good girl!” Dad said, eyeing the unwieldy stack, then turning to the boys, he offered,

“Hey, let me help you.”

“That’s all right, sir—just tell us where you want them.”

I wasn’t to know it then, but I’d just met two of Ursula’s most ardent admirers—soon to become rivals: tall, unassuming Alex Koslov, and his complete contrary—stocky, conceited, Grant Brigham.

As the day progressed, I learned that Weihsien had originally been a university campus, and that the long cellblocks had been student housing. Each block consisted of a row of twelve small rooms, measuring nine-by-twelve feet, that looked out onto a narrow, tree-studded compound and the back of the next row of rooms. The compounds were connected at each end by latticed brick walls and decorative gateways.

Each room had a door and standard window in front, and a little, high, clerestory window at the back for air circulation. They hadn’t been used by students in years, and before we arrived, had housed soldiers of the Chinese Puppet Army. The rooms had all been badly neglected; the white plastered walls were peeling and in need of repair, and the only electrical fixture was a ceiling lamp, hanging from a frayed cord.

When we moved in, Margo put her canvas cot under the front window, and I fitted mine, foot-to-foot with it, along the right wall. Ursula’s cot was across from mine on the left wall. There was a high, three-foot-long shelf with a rod under it at the end of Ursula’s bed to hang our clothes on, leaving just enough room for a crate to sit on and the door to open. It was very primitive, and along with the communal biffy a hundred feet down Main Street, it was to be our home for nine hundred and thirty-five days.

As soon as I had made up my cot and stashed my suitcase under it, I stepped out into welcome sunshine to explore. I found the camp divided up into a myriad of compounds and courtyards with airy latticed walls, many graced by moongates and pretty tile-roofed gateways, enclosing administrative offices, kitchens, two-story classroom buildings (now made into dormitories), and living quarters. There was an all-pervading flavour of the Orient throughout, and I couldn’t help thinking that it must have been a lovely place once.

Going through one more little compound, I stepped out onto a basketball court with a large, L-shaped building on two sides of it.

Surprisingly, it did not have an oriental flair, but was a tall, three-storied affair of solid Western design. I was wondering what it housed when I felt a gentle tap on my shoulder. As I turned, I saw Dan Friedland, an old friend from convent outings.

“I knew I’d find you, if I kept on looking,” he said with a lopsided grin. That’s what I’d always remembered about Dan—his tall, gangling, good looks, and that infectious smile. I’d met him one weekend when Aunt Kitty wasn’t feeling well and had asked if we’d mind staying with the Blessings. Claire, their daughter, was a day scholar at St. Joe, and she and I were always at loggerheads. I felt she tolerated our company that day, because her parents made her, but after the first outing, the scene changed: Ursula had hit it off with one of the boys in Claire’s group, so from thereon, we were always invited to join them on our monthly outings. I still felt like a tagalong though as Ursula was the one with the boyfriend; it wasn’t until Dan, with his zany American sense of humour, made me feel like one of the crowds that I got to enjoy those Sunday excursions.

“Where were you on the train?” he asked.

“I looked for you, but I never saw you.”

How could I tell him I was fighting with a rabid communist and hadn’t given him a thought! I was really glad to see him now, though, and I told him so.

He grinned and asked,

“Know where you are?”

“Haven’t the foggiest.”

“Well, that there building there,” he said, affecting a drawl, “is the hospital.”

“Really? I was trying to figure out what it was when you came up.”

“Well, now you know.”

“Bet the rooms in it aren’t as tiny as the one that was assigned to us.”

“For your information, all the cells are the same size, so don’t go around feeling you’re being dumped on. Next thing you’ll be saying is you don’t feel well and need a stay in the hospital!”

I laughed. “You read me like a book!”

“Just one of my talents,” he said in mock modesty, adding,

“Actually, what are you doing here?”

“Just nosing around. Think I’d better start looking for my cellblock, though, before Margo and Urs think I’ve gone over the wall.”

“Where is your cellblock?”

“Just off Main Street, directly across from Number Two Kitchen.”

...

[read further] ...

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/MushroomYears/Masters(pages).pdf

#