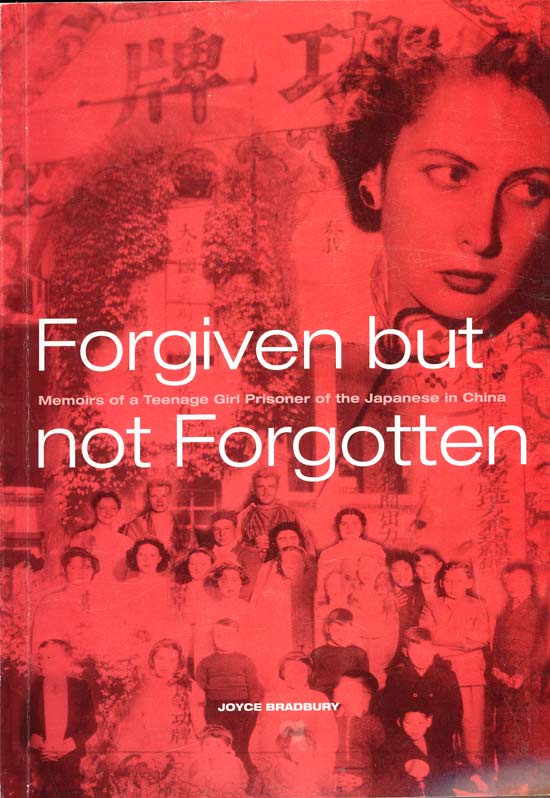

chapter 5

Teenage prisoner of the Japanese

Our group was the first Japanese internment prisoner batch to arrive in the Wei-Hsien camp and thus we bore the brunt of the camp's initial cleaning up.

As the days went on some 500 Catholic priests, brothers and nuns arrived together with clergy from a diverse mix of other denominations. About 1500 more civilian internees were also brought to the camp. For the first few weeks we had a big clean-up and committees were formed to set up and staff schools, the hospital, a bakery, a shoe repair shop and kitchens.

No clothing was issued by the Japanese during the next three-and-a-half years. As children grew out of clothing it was swapped at the exchange stall set up specially, which we called the White Elephant Exchange.

Internee arrivals trickled in from many parts of Japanese-occupied China. Many came from Tientsin (now called Tianjin), Peking, Chefoo and Tsingtao. Among the adults were professors, teachers, scientists and doctors. There were tradesmen, including butchers, bakers and carpenters, and ordinary businessmen. There were single men and women and many married couples ― with and with-out children.

Most of the prisoners were of British and American nationality. There were Eurasians and Asians from other countries. There were several Chinese prisoners including an American called Mr Chu. He was tall with an attractive part-Chinese wife. The criterion for internment was citizenship of countries with which Japan was at war but the Japanese interned some who were from neutral countries. Besides the British and Americans, the nationalities in the camp on June 30, 1944 [21] included Australians [22], Cubans, Greeks, Belgians, Iranians, South Africans, Canadians, Poles, Portugese, Dutch, Norwegians, New Zealanders, Uruguayans, at least one German who apparently also had American nationality, Filipinos, Palestinians, Panamanians and some Russians. The age range of the internees was wide. The eldest internees in mid-1944 were a missionary couple both aged 86. The youngest internee was a one-month-old infant. Because so many school-children had been brought to the camp, there was a disproportionate number of children at the time the list was compiled.

[21] List of internees dated June 30, 1944 giving names, marital status, nationality, age, sex and occupation. Bradbury family collection. Pamela Masters in her memoir The Mushroom Years, published 1998 by Henderson House Publishing, Placerville, California, writes of at least one French national acquaintance in the camp. However, the list of internees mentions no people of French nationality. See Further Reading.

[22] The number of Australians and New Zealanders in the camp list of internees appears disproportionately high compared to the other major nationalities – British and US. Most of the Australian males were either missionaries or businessmen. Analysis of the countries where the Wei-Hsien internees settled after liberation suggest that Australia and New Zealand took a disproportionate number of them. This latter observation is based on address lists I have been given at international reunions of camp inmates. Bradbury family collection.

Some of the imprisoned Catholic clergy belonged to strict religious orders which meant their lives were lived in monastic silent contemplation under sparse conditions. They were rounded up by the Japanese and brought into the camp. As my family members were already camp inmates we saw their arrival. Some of these monks had long hair and beards which they were forced to remove. I remember some of them being handsome young men when we saw them the next day, clean shaven, hair trimmed, wearing donated shorts and shirts. Many of them gazed about in wonder during their first days in the camp but they soon became friendly with the young girls and boys in the camp, of which there were many.

As we began to settle down the various committees allocated duties to every-body over the age of 14. Doctors and nurses were assigned to hospital duties and caring for the health of people while tradesmen worked in the carpentry and other shops. In general, the women had to peel vegetables and the men worked in the kitchens irrespective of their former callings.

The clergy also worked. They performed kitchen duties, stoked hot water boilers for the showers and pumped water which had to be done 24 hours a day. They also helped with heavy work such as lifting when required. One Catholic priest, Father Schneider [23], was formerly a shoemaker and he was put in charge of the shoe repair shop. Some of the nuns worked in the kitchen, cleaning vegetables, and also taught in the schools alongside Protestant missionaries. Some nuns nursed and some volunteered for the terrible job of clearing overflowing toilets, which they did with grace and dignity. The nuns wore veils over a stiff cloth frame called a ‘coif’ on their heads when they first arrived. After a while, they dispensed with the coifs and just wore a veil pinned to their hair. Many of the Protestant clergy had added tasks. They had to tend to the needs of their families, of which there were quite a few.

[23] Father Schneider was a Franciscan friar. In my autograph book he wrote in rhyme of his cobbling under the heading `We aim to Please'. It went:

"For all the coining years in Wei-Hsien,

1944 -45-46-47-48-49-50-51-52-53,

When Life's foundation totters,

Visit Wei-Hsien's one and only shoe shop."

This is followed by his signature and the date: New Year's Day 1944.

Bradbury family collection.

Everybody I knew worked hard for the benefit of the whole camp and I am not aware of any problems with persons not pulling their weight. There were four kitchens and dining rooms. Because of the food supply situation, it was a big job trying to satisfy the hunger of the inmates. Sadly, that was never really achieved. My father, a qualified accountant, was given cooking duties in a communal dining room where meals were cooked and served in relays. Mum also worked in the kitchen and made craft goods.

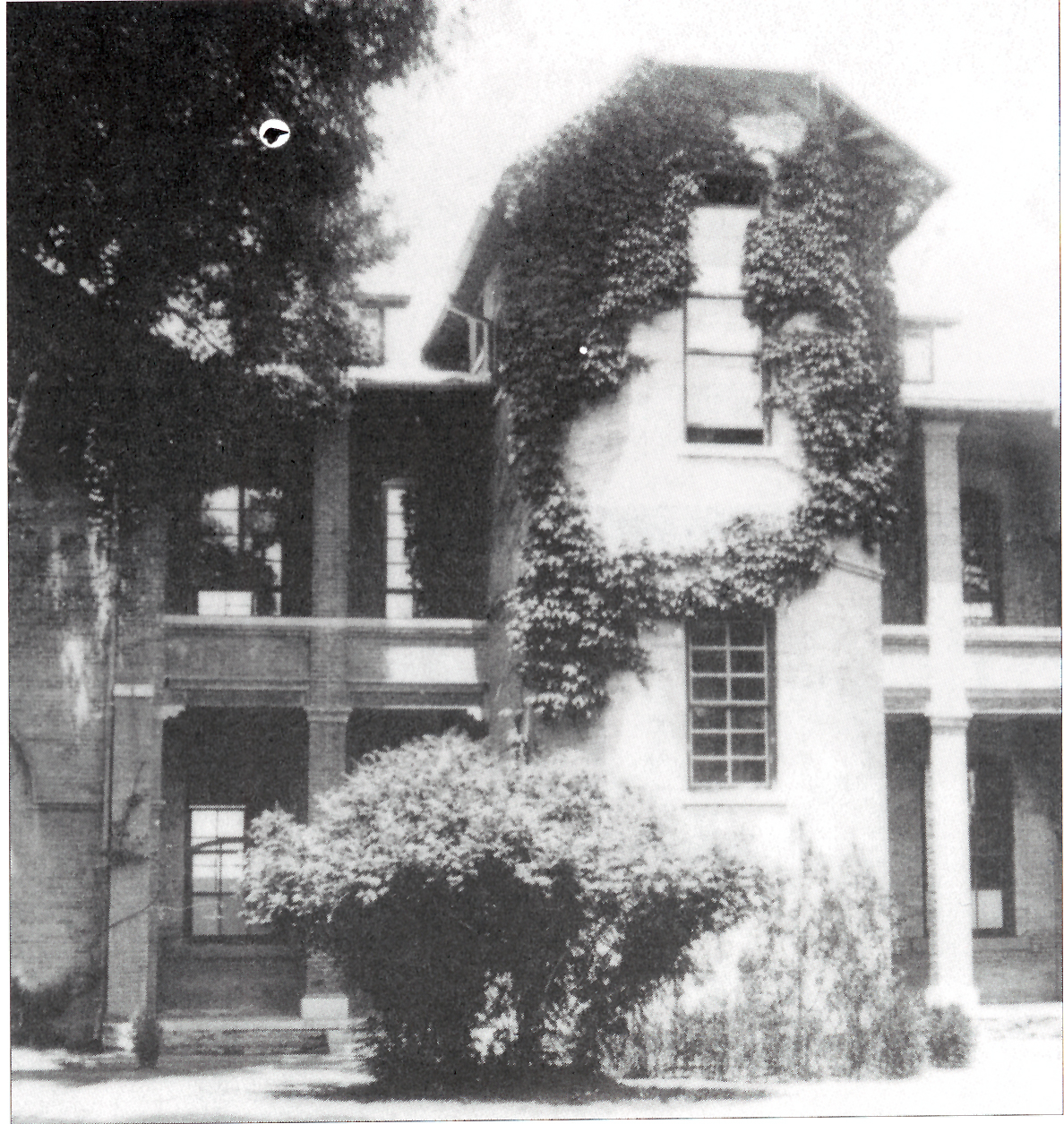

A dormitory block at the prison camp.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo

[click here]

Our food was sparse and we were always hungry. It was usually boiled sorghum seeds for breakfast. Sorghum is usually grown in China for livestock feed. It is made up of little red seeds which are awful to eat but I have since been told they are a good source of protein, fibre and energy. They are difficult to swallow and I had to chew and chew them. My mother would say: "Keep chewing it until you can swallow it or you will go hungry." Lunch would usually consist of one scoop of a thin vegetable stew. We were issued with a little tin plate and a tin cup. We had potatoes, carrots, leeks and Chinese turnips. The camp cooks were ingenious but the food was insufficient.

Sometimes there was enough for second helpings but not often. On these occasions, the extras would be served at half a scoop. Families often put their whole ration into a larger container to take back to their rooms to eat. Somewhat surprisingly, there was never any rice for us. I presume it all went to the Japanese military.

It was very difficult for the younger children. They had to go hungry and they did not understand what was going on. The rest of us just had to put up with the shortages. We were given some flour, which the inmates made into bread. The bread always tasted stale to me, although it was freshly made. We had peanut butter because Wei-Hsien grew a lot of peanuts. The peanuts were ground by hand either in the bakery or the kitchen and that's what kept us going. I still like to eat peanut butter [24].

[24] Sister Rosemary Lynch RN, of the Mater Hospital in Brisbane, Australia, has told me that peanut butter is an excellent food often used in treating people suffering malnutrition in poor countries.

On one occasion a load of potatoes was delivered and dumped in a corner of the parade ground. The Japanese would not allow us to move the potatoes and they were left out in the weather until they started to rot. We were then told to eat them and when the inmates complained, the Japanese said: "You'll get nothing else until the potatoes are eaten." So, we ate them.

When a horse dropped dead behind the camp near the Japanese officers' quarters, the Japanese refused to let the inmates eat it until it was maggoty and putrefying rapidly. They said, once again: "Eat it ― you'll get nothing else until you do so." The inmates promptly skinned the carcass and removed the rotten areas as much as possible and stewed the rest. We were rarely served meat.

Some inmates brought canned food with them into the camp but my family did not. One of our family's good friends, a wealthy lady, brought a fairly large quantity of canned and preserved food into the camp and although she had been allocated work by the committee, she preferred to employ others to do her share on the payment of her food to them. Eventually, she ran out of supplies and then had to do her share of work. We kept in touch with her until she died several years ago. In her latter years she showed us a thick coil of malleable gold which could be worn around her wrist saying: "If ever I have to go into camp again, I will take this gold with me and cut off little bits to use to buy food."

I do not remember any shop in the camp where we could buy necessities such as food or toiletries although I have since been told there was one for a short period of time. A cake of soap was issued now and again. We used that to do our laundry outdoors in large round tin wash tubs with two handles. We had to cart our laundry hot water in buckets from the shower block boiler.

Many people desperate for a smoke rolled used dry tea leaves into cigarettes and smoked them. My mother who was a heavy smoker did this, but after a lot of urging from my father she gave up smoking for the rest of the war.

While there was a shoe repair shop in operation, new shoes were non-existent and when my brother Eddie wore his shoes out, mum made a pair out of canvas for him. It took her days to sew them but he wore them to pieces within a couple of hours. Many of the children went barefoot. My mother was more successful at making cloth toys for children which she used to trade with other inmates for canned and preserved food.

I attended school in the camp. It was conducted by nuns, priests and staff from the Peking American High School. Most of the teachers were university trained. My father used to say to us: "You are getting the best education because these people are some of the most highly trained teachers in the world." Text books were scarce and we had to share them. We had pencils and paper and some had fountain pens. We were given homework most nights.

On completing school in the camp at the age of 17 I was presented with a graduation certificate signed by Alice Moore, my camp school's principal. Before her imprisonment, Miss Moore was principal of the Peking American High School. Amazingly, Miss Moore brought the blank graduation certificates with her and other necessities such as books for running a school in the camp. I still have the graduation certificate which says I graduated from the Peking American High School. I separately studied shorthand while I was attending high school in the camp. I still have my certificate [26] of competency at a rate of 60 words per minute.

[26] Family document. Bradbury family collection. It says that I graduated from the Gregg Shorthand School, Tientsin. Grace Norman, the principal of the school who was in the camp with us has crossed out Tientsin and inserted Wei-Hsien and the date: April 28, 1945. Mrs Norman had brought the pre-printed certificates with her into the camp.

Other schools operated in the camp. This was done to help children who had been educated together before the war to remain together in school at the camp. The Chefoo School, which the Reverend Norman Cliff and his siblings attended as students, operated in the camp. The school was well-organised with sporting teams and a Boy Scout group.

As soon as I turned 14 in mid-1942 I was given the regular job of cleaning toilets. I was given a bucket, a brush, some cloth and disinfectant. Every day I had to clean the ladies' and gents' toilets near the communal showers. There were no sewered or flushing toilets.

Things settled into a routine. Everything was managed and well-conducted by the camp's committees.

I remember very well how cold it was in winter because there was no decent heating. We made coal balls from Japanese-issued coal dust with water and then dried them in the sun. We burnt them in a mud stove in the corner of our room during the cold weather. We had to guard our supply because pilfering did occur.

Japanese soldiers [28] patrolled through our sections of the camp all the time ― carrying rifles. They always thrust their rifles towards us when giving an order or counting us during roll call. We rarely saw Japanese officers in the camp, only the soldiers with their little caps. Members of the camp's committees would regularly confer with the Japanese officers about problems faced by the inmates.

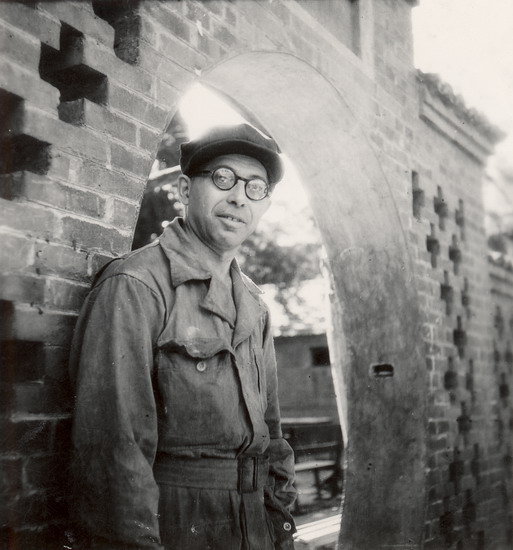

Leo with a heart of gold --- [click here]

[28] In his unpublished memoir This is Leo's Life by Lionel (Leo) Harold Twyford Thomas (1905-2000) a camp inmate, Leo writes of the camp soldiers: "We were very lucky that the ordinary guards at the camp were ex-consular staff, [In other words, they were poorly trained combat garrison troops sent to earlier protect Japanese commercial and consular interests in China] and not regular army officers, with only the head honcho an [well-trained combat] army man." Whatever they were, I found them frightening on most occasions.

I lost weight but otherwise remained healthy except for tinea of my toes for which one of the doctors gave me Condy's crystals which helped heal them. My brother went to the camp hospital and received treatment for a cut lip.

During our imprisonment my brother was still recovering from tuberculosis. The doctors handled limited supplies of milk and eggs for babies and children under 10. Because Eddie turned 10 at Wei-Hsien, he did not qualify for the milk and eggs. This annoyed my father who thought he should receive milk and eggs to help him recover. Pop was working in the cookhouse one day wondering how he could get nourishing food for Eddie when a pigeon flew in through a window and fell into a vat of boiling soup. In no time it was plucked, cooked and fed to my brother. Pop always said the impromptu pigeon meal saved young Eddie's life.

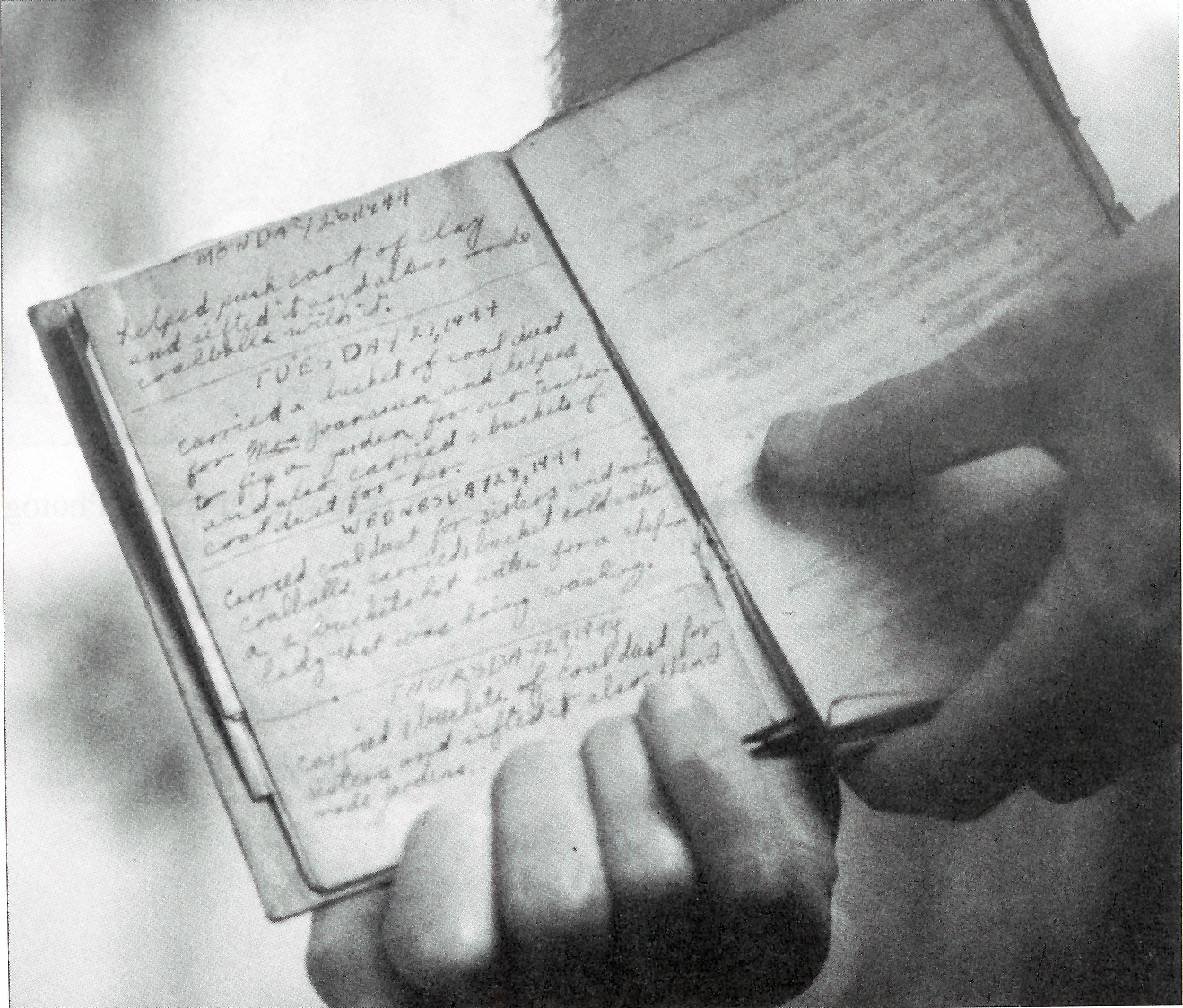

Eddie's Boy Scout 'daily good deeds' book compiled in prison.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

[click here]

There was a black market in the camp. Chinese used to pass food through holes in the camp's perimeter wall under cover of darkness and payment would be made in money or articles of jewellery. My wristlet watch went this way because my parents had no jewellery to barter. Sometimes, the food was donated by Chinese friends of inmates.

Our room was near the perimeter wall and Pop made a hole in it by removing a brick. Pop used to act as a blackmarket buying agent for others. Mr de Zutter used to be his lookout and if he saw a guard coming he would warn Pop by saying: "Good night, I'm going to bed now," or starting to whistle. On one occasion my father was buying the Chinese sorghum-based wine called bygar when he was almost caught by the Japanese. He ran and jumped into his bed fully clothed, leaving the wine bottles on the table where my mother found them next morning.

One of the internees, Father Patrick Scanlan [29] [also known by his adopted religious name of Father Aloysius after Saint Aloysius Gonzaga], was an Australian Cistercian (Trappist) monk who lived in a faraway monastery, well north of Peking, before imprisonment. Father Scanlan became our best blackmarketer. He specialised in obtaining food for the other inmates ― which he did for no profit. Some of the food he bought from the local Chinese came into the camp in large quantities. Its arrival supplemented our sparse Japanese-supplied rations. Amazingly, he was able to get special food wanted for the hospital inmates.

[29] Father Scanlan's autobiography Stars in the Sky, published by Trappist Press, Hong Kong, 1984, extensively deals with his internment by the Japanese (pp 122-184). He relates some of the issues and incidents I mention in this book.

Father Scanlan was taken with most of the other Catholic religious (about 400 priests, nuns and brothers) from the camp on August 16, 1943 to Peking where they were interned in monasteries, seminaries and convents until the Japanese surrendered in Peking on August 19, 1945.

Father Scanlan suggests the Japanese agreed to the removal of most of the Catholic clergy because Vatican officials argued with Japanese officials that the Catholic clergy were – if a citizen of any earthly country – citizens of the neutral Vatican state and thus should not be interned. Separately he suggests, the Vatican officials argued the Japanese could need the Vatican as an intermediary for any future negotiations of a Japanese ceasefire with the Allies. At the time of the removal of these clergy from Wei-Hsien, Allied victories in Asia against the Japanese were starting to mount.

The departure of many of the Catholic clergy from Wei-Hsien was deeply moving. Many of them had been our teachers before camp and in camp. While in camp they became our friends, carers and co-workers. They were never shy of volunteering for hard work and they were great bearers of comfort to all. As they were taken away there were real fears among us watching their departure that they would be massacred. It was a terribly sad day, the day they left. Many cried, regardless of religious persuasion.

Some Catholic clergy stayed behind until liberation to minister to the camp population and engage in tasks for which they were specially equipped such as teaching and nursing.

After a short post-war period in China, Father Scanlan returned first to a Trappist community in Wales. [The correct term for Trappists are members of the Cistercian Order. The term, Trappist, comes from La Trappe in Normandy, France, where there is a Trappist abbey. Trappists practise a stringent rule of austerity and silence.] Father Scanlan subsequently returned to China for a short time before joining Trappist communities in Canada and the United States. In the early 1950s, Father Scanlan left the Trappists and became a diocesan priest in the United States where he served parish communities on the east and west coasts.

Two of the Trappist monks with Father Scanlan at Wei-Hsien and Peking – Fathers L' Heureux and Drost – after their eventual release from internment returned to their Trappist monastery north of Peking. They were later taken into custody by Chinese Communist forces with other priests, brothers and students of the Trappist community and treated brutally. As a result of the hardships and torture they suffered, they died. They are two of the 33 people from the Trappist community in China who have been put forward as worthy candidates for canonisation as saints by the Catholic Church. Their candidature is still pending (February 2000) because the present Chinese authorities are opposed to permitting hearings about the nature of their deaths in China.

Once Father Scanlan was kneeling at the hole in the wall doing his black-marketing business when a guard came up. Father Scanlan immediately took out his prayer book and told the guard he was reading his prayer book and praying. The guard didn't believe him because he knew even Japanese couldn't read in the dark. Father Scanlan said he didn't need light to read because he knew all the pages by heart.

This did not convince the guard and Father Scanlan [30] was locked up behind the Japanese officers' quarters and sentenced to solitary detention for two weeks by the camp commandant. His solitary confinement would have come as a breeze for Father Scanlan because he had spent more than half his life living in a monastery. To upset his captors, Father Scanlan, in the first several days of his confinement, chanted his prayers in Latin at the top of his voice. He continued night and day telling the sleepless Japanese officers that it was his duty as a priest to daily recite his mandatory collection of prayers called the priest's office. Catholic priests daily say their office, generally silently or quietly. The Japanese were too superstitious to stop him. After several days, when the Japanese could stand our blackmarketing priest's sleep-disturbing prayer chanting no longer, they released Father Scanlan.

[30] The imprisonment of Father Scanlan inspired a song which we all quickly learnt. It is sung to the tune of If I had the Wings of an Angel. Called The Prisoner's Song, it was penned by an anonymous inmate. Its words are:

Oh, they trapped me a Trappist last Wednesday,

Now, few are the eggs to be fried,

So, here in this dark cell I ponder,

If my clients are empty inside.

There's a great big basket on the outside,

Just brimming with honey and jam,

But how can it come onto our side,

If the bootleggers don't know where I am?

It is dated 1943.

Family document, Bradbury family collection.

News of Father Scanlan's release triggered one of the most joyous days in the camp. Everybody came out and cheered him. The Salvation Army members in the camp co-led by Father Scanlan's fellow Australian, Salvation Army Major Henry Collishaw [31], assembled. They escorted Father Scanlan through the compound with their 20-piece band blaring away. It was a joyful occasion for us and for Father Scanlan. The Japanese guards were surprised by our reaction to Father Scanlan's release. However, they took no punitive action. Without delay, Father Scanlan immediately resumed his blackmarketing.

[31] There are 48 references to Henry Collishaw and his wife Florence in the official history of the Australian Salvation Army. After the war, he rose to the rank of Brigadier.

Father Scanlan was a genial man, always smiling. He had a beautiful singing voice. He was a gentleman who was thoroughly well-respected and loved by us. Behind Father Scanlan's outwardly quiet appearance dwelt a brain as sharp as a tack and he used it for the benefit of the inmates.

"For all the coining years in Wei-Hsien,

1944 -45-46-47-48-49-50-51-52-53,

When Life's foundation totters,

Visit Wei-Hsien's one and only shoe shop."

This is followed by his signature and the date: New Year's Day 1944.

Bradbury family collection.

A dormitory block at the prison camp.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo

[click here]

Leo with a heart of gold --- [click here]

Eddie's Boy Scout 'daily good deeds' book compiled in prison.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

[click here]

Father Scanlan suggests the Japanese agreed to the removal of most of the Catholic clergy because Vatican officials argued with Japanese officials that the Catholic clergy were – if a citizen of any earthly country – citizens of the neutral Vatican state and thus should not be interned. Separately he suggests, the Vatican officials argued the Japanese could need the Vatican as an intermediary for any future negotiations of a Japanese ceasefire with the Allies. At the time of the removal of these clergy from Wei-Hsien, Allied victories in Asia against the Japanese were starting to mount.

The departure of many of the Catholic clergy from Wei-Hsien was deeply moving. Many of them had been our teachers before camp and in camp. While in camp they became our friends, carers and co-workers. They were never shy of volunteering for hard work and they were great bearers of comfort to all. As they were taken away there were real fears among us watching their departure that they would be massacred. It was a terribly sad day, the day they left. Many cried, regardless of religious persuasion. Some Catholic clergy stayed behind until liberation to minister to the camp population and engage in tasks for which they were specially equipped such as teaching and nursing.

After a short post-war period in China, Father Scanlan returned first to a Trappist community in Wales. [The correct term for Trappists are members of the Cistercian Order. The term, Trappist, comes from La Trappe in Normandy, France, where there is a Trappist abbey. Trappists practise a stringent rule of austerity and silence.] Father Scanlan subsequently returned to China for a short time before joining Trappist communities in Canada and the United States. In the early 1950s, Father Scanlan left the Trappists and became a diocesan priest in the United States where he served parish communities on the east and west coasts.

Two of the Trappist monks with Father Scanlan at Wei-Hsien and Peking – Fathers L' Heureux and Drost – after their eventual release from internment returned to their Trappist monastery north of Peking. They were later taken into custody by Chinese Communist forces with other priests, brothers and students of the Trappist community and treated brutally. As a result of the hardships and torture they suffered, they died. They are two of the 33 people from the Trappist community in China who have been put forward as worthy candidates for canonisation as saints by the Catholic Church. Their candidature is still pending (February 2000) because the present Chinese authorities are opposed to permitting hearings about the nature of their deaths in China.

Oh, they trapped me a Trappist last Wednesday,

Now, few are the eggs to be fried,

So, here in this dark cell I ponder,

If my clients are empty inside.

There's a great big basket on the outside,

Just brimming with honey and jam,

But how can it come onto our side,

If the bootleggers don't know where I am?

It is dated 1943.

Family document, Bradbury family collection.

Father Scanlan on his 100th birthday in California. To the left is his signature in my prison camp autograph book.

Photograph montage: Georgie Perry, photograph of Father Scanlan, Sister Marie Masbridge.

Father Scanlan had a narrow escape on another occasion when he had about five dozen blackmarketed eggs hidden in his upper clothing. He was confronted by a guard. He immediately squatted on the ground and said in Chinese: "dootzetung, dootze-tung" which means sore tummy or diarrhoea. Because this was a common ailment, the Japanese soldier believed him.

My good friend Stanley (Stan) Fairchild, who now lives in Hong Kong, was one of our most adept blackmarketers. He was often Father Scanlan's right-hand man even though he was only 12. Stan also had a couple of narrow escapes from being caught.

People like Pop, Stan, and Father Scanlan helped keep us alive during these years and we were all very grateful to them. Most of the blackmarketed goods brought into the camp consisted of eggs, vegetables and sugar.

Occasionally, the Chinese smuggling goods to the camp were caught and they were given a severe beating by the Japanese. There were suggestions in the camp that two Chinese were shot for smuggling.

Japanese guard post at the camp. Done by fellow prisoner.

Photograph: Georgie Perry

[click here]

Some of the camp's inmates would do almost anything for alcohol. One of the women had brought a lot of valuable perfume into the camp. Her alcoholic husband drank it. Two men and a woman, so we were told, allegedly made alcohol from wood shavings collected from the carpenters' shop and other materials. They died after drinking it. One of the doctors warned the inmates that drinking such brewed drinks was dangerous because of their potentially high wood alcohol [methanol] content. I did not hear of anybody else dying from drinking wood alcohol. However, considerable amounts of bygar wine were smuggled into the camp. What the teetotal missionaries who built the camp would have thought of this trade remains ponderable.

Some Red Cross parcels were received at the camp. The arrival of the first lot led to bad blood because some Americans claimed they should solely have them because they came from the American Red Cross. When a second lot of Red Cross parcels arrived, the question of their distribution was solved after discussions the camp management committee had with the Japanese camp commandant. The Japanese ordered the parcels to be fairly shared or they would be with-drawn. Incidentally, the Red Cross parcels received at the camp over the internment years came from the Australian Red Cross and the American Red Cross [32]. The Australian Red Cross parcels were arranged by a Sydney relation of the interned Tipper family from Australia.

[32] Unpublished memoirs: This is Leo's Life by Lionel (Leo) Harold Twyford Thomas, Bradbury family collection.

In the Red Cross parcels were chocolates, canned and packet food and knitting needles with wool. There was some clothing too. I will never forget the candy-coated Chiclets chewing gum that I received as my gift in the American Red Cross parcel sharing. After chewing it all day, I stuck it each night on the side of the cupboard near my bed and placed it in my mouth the next day. I did that until the chewing gum disintegrated. I also received a frock which came in one of the parcels. It was a winter dress of woollen material and I still have a photograph of myself wearing it after the war. Towards the latter stages of the war the Red Cross parcels stopped coming.

One of the perks of working in the food areas was taking home extra food. My father was able to bring home dripping once in a while which we ate on our bread. We were always hungry and fantasised about food. Some people thought about milk and sugar because we had to drink tea without milk or sugar. The tea was ladled out to us from large pots. My mother missed her coffee and we all missed bacon and eggs. I do not remember anyone putting on weight. Some inmates were caught by other inmates stealing vegetables, bread and other food. They appeared before a camp committee which decided whether they were guilty or not. I don't remember what punishments were inflicted except the names of the guilty were put on the notice board.

It is possible some of the priests, particularly the Trappist Father Scanlan and the Belgian Father Raymond De Jaegher [34], who was a seminary professor, actually ate better in the camp than they did before imprisonment because pre-camp they lived mainly on bread and water. Father Scanlan often said that. I was never quite sure whether he and the other priests were trying to bolster our spirits. I knew that Trappists were required to live under severe rules of austerity and silence [35] and Father Scanlan writes in his book [36] that meals in the monasteries were always spartan.

[34] Father Raymond J De Jaegher wrote his memoirs of the camp in a book titled: The Enemy Within. It was published by the Society of St Paul, Bandra Bombay – 50, in 1969. A Sinologist, who was extremely fluent in Chinese, he set up a highly successful postal communications systems with the outside world from the camp using supportive Chinese. Consequently, he was a significant gatherer of intelligence information which was supplemented from time to time with secret monitoring of Allied news broadcasts using secret radios in the camp. These broadcasts detailed Allied successes in the war against Japan.

Father De Jaegher played a key role in organising the only escape from the camp, and was a significant adviser to the camp's management committee in general matters of dealing with the Japanese. As the Allies' war progressed against the Japanese, Father De Jaegher noted a decline in the guards' morale. He advised the committee on how to treat with Chinese Communist-led forces. These forces, towards the end of the war, began encircling the Wei-Hsien area. His advice to the committee possibly averted a massacre of the camp's inmates.

He recommended the camp leaders not to provoke a revolt by the camp's inmates as suggested by the Chinese Communists in a secret communication to the camp. He warned a camp revolt could lead to the gathering Communist forces – who were no friends of non-Chinese (contained in the camp) and the Japanese guards – massacring both the inmates and the Japanese. He counselled that the camp patiently wait for Allied liberation. His suggested strategy was accepted by the camp's leaders.

They were guided in that decision by Father De Jaegher and others analysing the information they were gathering from secret radio monitoring and incoming documentation being brought in secret messages by the Chinese toilet coolies [see text]. His advice was later proven to be well-founded. In the last days of the repatriation of liberated internees from the camp, Communist forces blew up the key Wei-Hsien railway infrastructure. This forced the Allied forces to fly out the last remaining Wei-Hsien internees.

Post-war, Father De Jaegher again largely worked in Asia. He became internationally famous as an anti-Communist campaigner and prominent as an adviser to the largely Catholic-led, anti-Communist leadership of South Vietnam. This country was formed in the mid-1950s following the 1954 collapse of French-led forces to Vietnamese Communist forces. A partitioned Vietnam into south and north sectors then followed as a result of international talks. South Vietnam eventually fell in 1975 to Communist forces, despite protracted and considerable military and financial support from the US and other countries including: South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand. This Viet Cong success led to the reunification of Vietnam from South and North Vietnams into present-day Vietnam, a Communist state.

See also Further Reading.

[35] Because of the Trappist monks' imprisonment and the need for the monks to verbally communicate, the Catholic bishops who were also interned agreed after a synodal meeting that the Trappist monks could be released from their vow of silence during their internment in the camp. The monks quickly took full advantage of the bishops' ruling. They became loquacious. It was to our amazement. As children, we solemnly believed that the Trappists could only speak when saying prayers alone.

[36] Stars in the Sky by Father Patrick Scanlan. Published by Trappist Press, Hong Kong, 1984.

I remember when a new commander of our camp, a Japanese officer named Koyanagi, arrived to take charge. He recognised my father as being a prewar business associate of his. He seemed surprised to see us in there and showed signs of friendship by bringing us water melon and fresh eggs. After several visits my father thanked him but asked him not to show us any favours because it was unfair to other inmates and embarrassing to him. The gifts and visits ceased.

A pressed flower from the prison given to me when sick.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

English and some Chinese were mainly spoken in the camp although there were many different nationalities there.

The toilets I had to clean were holes in the floor. They were not sewered. In addition, each compound area had toilet pan systems that were emptied by coolies who visited the camp and took the contents away for their gardens. The coolies were a splendid source of information from the outside world. Various methods were devised to receive notes. Sometimes bits of silk with messages on them were hidden in wall cavities for the coolies to collect and carry the notes in their mouths from the camp. The Japanese guards were vigilant and changes to the note exchanges had to be constantly made before they found out what was going on. Sealing the notes in tins and placing them in almost full toilet pans was discontinued because the guards began probing the pans with rods.

The most successful method of smuggling in notes from pre-war friends and contacts was developed by the coolies. They would push a note up into their nostrils before they entered the camp and then blow it out onto the ground at pre-agreed areas. The note would then be collected by a specially appointed camp inmate. The Japanese never detect this message exchange system.

The information contained in the messages was spread by word-of-mouth. I was not aware at the time but I have since been told there was also a radio receiver in the camp which was not found by the Japanese.

I cannot remember any specific war news of the time but I remember my mother used to say when we had unscheduled head counts: "Uh! They've lost another battle." Some of the information must have been encouraging because I felt for the most part that we would be freed eventually. But as the years went on our spirits occasionally sagged. We did occasionally see aeroplanes high up in the sky. Sometimes we could hear them. But we didn't know whether they were Japanese or Allied.

There were rumours of some suicides in the camp but they were never confirmed to me. It was also claimed that some female inmates were put into a special section of the camp hospital for treatment of depression.

There was no piped water in the camp but there were wells. To cater for the whole camp of some 2000 people the well pumps had to be hand-operated 24 hours a day and a number of men were kept at this work. We were allowed one shower a month in a communal bathroom. The bathroom consisted of about 12 showers and three or four hole-in-the-floor toilets. We were rostered alphabetically for hot showers. My second cousin Bob (Bob Cooke whose father ― my great-uncle Edward ― was also in the camp) was one of the stokers of the boilers.

In our individual living areas there was no running water so we used to wash in a dish of carted hot water. It was like having a birdbath. One of our fellow prisoners was a Miss Ponds who my mother used to say was an old maid. Miss Ponds would never strip for a shower but would wash herself wearing a petticoat. As 13-14-year-olds we used to wonder what she had that we didn't. With my girlfriends we used to pretend to drop the soap and take a peep but we never did find out what she had under that petticoat.

We had births, deaths and marriages in the camp. Some children were born out of wedlock, which was hardly the done thing in those days.

There were romances of course and I had boyfriends as all young girls did then and still do now. There were fights between young men vying for a particular girl but I don't remember anyone fighting over me. Everybody knew who was interested in whom because there was absolutely no privacy ― even whole families slept in the same room.

The medical doctors and nurses ran the camp hospital with great efficiency. There were many patients with illnesses and injuries. On one occasion late in the war, some medical drugs came to the camp hidden in Red Cross parcels. We were told the Japanese removed the labels from the containers. The absence of the labels was very troublesome because our doctors had to try to analyse the contents to find out what they were. Some of these drugs were the then new and highly effective anti-bacterial sulpha [37] drugs. I have recently been told that the drugs were hidden in the Red Cross parcels by Chinese Nationalist forces who had received them at their nearby base from an Allied air drop. The drug labels were removed to prevent them being detected by Japanese searchers when the Red Cross parcels were delivered to the camp. A short time after the drugs were delivered, Father De Jaegher obtained information on the delivered drugs from the Chinese Nationalists and their recommended methods of usage which he gave to the hospital doctors. The doctors and those who assisted them in the hospital did a splendid job for the inmates. They also treated the Japanese when they needed medical attention.

[37] Sulpha or sulfa drugs belong to a group of anti-bacterial drugs derived from the red dye, sulphanilamide. They were first discovered by a German chemist in 1935. According to the Concise Colour Medical Dictionary published by Oxford University Press, Oxford in 1994, the use of sulpha drugs has declined in recent decades because of "increasing bacterial resistance to sulphonamides and with the development of more effective less toxic antibiotics".

A fellow prisoner with me was Eric Liddell, a London Missionary Society worker and teacher who taught at the Tientsin Anglo-Chinese College. He was the 400 metres gold medal winner for Great Britain at the 1924 Olympic Games and a former Scottish rugby international. He was born in Tientsin (1902) and was educated in China and the United Kingdom. He died in the camp from a brain tumour on February 21, 1945. He was greatly loved and respected. I attended his funeral and he was buried in the camp's grounds. The film Chariots of Fire [38] deals with a portion of his life story but does not cover the details of his life as a prisoner at Wei-Hsien. Mr Liddell was director of a sports program in the camp as well as a teacher and speaker at church services. Few of the camp children knew of him being an Olympic gold medallist.

[38] Chariots of Fire, a film, 1980. Directed by David Puttnam. Won the Oscar award given by American Academy of Motion Pictures for Best Picture, 1981.

Once, a number of young men and boys decided to have a running race around the inside of the camp wall, which we used to call `running around the block'. Mr Liddell, who was in his 40s, said: "I'll join you." Everybody laughed at him and said: "You're too old." He said: "I'll come along anyway." Off they went and he beat them all much to their amazement [39]. It was only then that some learnt of his prowess in running. From that time on he was even more respected by the young men.

[39] Second in the race was Lionel (Leo) Twyford Thomas who subsequently settled in Australia. He died in January 2000.

See also Further reading.

According to my calculations, the race was run over a distance of about 800 metres. This distance estimate is based on a detailed map of the camp prepared by the honorary Swiss Consul-General's representative, Mr V E Egger, who lived in Tsingtao.

During the war, Mr Egger also acted as the representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Mr Egger visited the camp on several occasions, bringing with him Red Cross supplies and money which was called comfort money. Inmates could apply for the money if they signed a promissory note undertaking to repay it after the war. Map copy is in Bradbury family collection. Mr Egger also issued in 1943 safekeeping receipts on Shanghai Swiss Consulate-General letterhead to my mother for personal jewellery she had brought to the camp and the title deeds to our Tsingtao home. The Swiss Government from late 1941 undertook to represent British interests in Japanese-occupied China.

Receipts are in Cooke family collection.

Everybody liked Mr Liddell because he was such a gentle modest man. He was married and had three children. His wife, who was pregnant with their third child, escaped internment because Mr Liddell sent them to Canada before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Another man I knew, Alex Marinellis, sadly missed out on liberation. A few days before our liberation, he slipped and fell while sawing a branch off a tree for firewood. I saw him fall to his death. He was 21.

We had dances in a dining room on Saturday nights. A specially formed dance band supplied the music. Because the camp lights went out at 10 p.m., the dances finished too early for us. In the camp there were some African-American musicians who played in the dance band. Members of the Salvation Army also had a band which regularly played for church services and recitals.

The Salvation Army members were good keeping up people's spirits. They constantly organised activities for younger children, visited the ill and encouraged people interested in learning to play a musical instrument. Reverend Norman Cliff, then a schoolboy, learned how to play the trombone from them [40] and used to perform at their recitals.

[40] ... "The year 1944, with all the problems I have mentioned, brought for me a bright and happy feature which offset many of the trials and tribulations of that period. A Salvation Army officer offered to teach me a brass instrument and invited me to join their band. [read further]

There was also a Dutch married couple known as the `holy rollers' because of their religious beliefs. They were members of a group of religious people who manifest their religious fervour by rolling on the floor while saying their prayers. They did their praying regularly because I used to see them from where we lived.

The Japanese sergeant who was responsible for our section of the camp was known to us as Sergeant Bushing-de because he always said no to any question and `bushing-de' in Chinese means `no can do'. We used to refer to another guard as slippery Sam because he was sly and slippery in his actions towards us. There was also a big guard nicknamed King Kong.

Captain Yumaeda, who was one of the camp's commandants, owned a nanny goat from which he used to obtain milk for himself and perhaps other officers. One day the goat wandered into the general camp compound and was immediately milked by the inmates until there was no more milk. My mother had a go at it but without success. Somehow or other we had some of the milk in our tea that day but I don't remember how we got it. It was lovely. The goat never escaped again. The scene of all these ladies chasing the goat to milk it was a sight I will always remember. Funny yes, but pathetic in retrospect.

At first there were no Italian inmates, but the surrender of Italy to the Allies before the collapse of Germany led to quite a number of Italians being brought into the camp late in the war. There were few Russians in the camp. My mother's Russian nationality brother, Boris, and his wife Natalie spent the war years in Dairen and Shanghai which were Japanese-occupied. There, he worked for Caltex.

The only pet animal in the camp was a little white fluffy dog brought in by a Dutch lady, Mrs Van Ditmars. I do not know how she arranged it but the dog stayed with her during the whole time we were in the camp. Mrs Van Ditmars was not accompanied by any members of her family and I can only assume the Japanese allowed her to have her dog for company. The dog did not want for attention from the camp's population. It was always in the best of health because one of the inmates was a veterinary surgeon.

Every morning at 7 a.m. and every evening all the internees had to stand out-side their rooms to be counted. Soldiers in their khaki uniforms counted us by pointing their rifles at us. It was frightening because we never knew if a rifle would go off. We accepted this as normal camp procedure but occasionally they banged on our doors and roused us from our beds at 1, 2 or 3 a.m. for an extra count. It did not matter whether it was raining, hailing or snowing. Out into the open we had to go; old people and babes-in-arms. There we stood until we were counted at rifle point. There were machine-guns and searchlights constantly trained on the compound from the sentry positions or guard boxes on the walls. These boxes are there to this day as are the insulators that used to carry the camp's perimeter electrified wires.

The impromptu head counts in the middle of the night started I was told because one of the bachelors who slept in a male dormitory climbed the bell tower one night and rang the bell. He was said to have been dared to do this by fellow bachelors. I understand that some of them had agreed to ring the bell when the war was over. However, the bell rang out well before the war was over. This bell was there because of the camp's previous incarnation as a religious institution. It was normally only rung when hot water was available for the inmates. The bachelor's unscheduled tolling of the bell caused considerable consternation among the Japanese. As a result, the Japanese then punished us all by turning us out at odd times for a head count, which took forever to conduct.

Another matter that enraged the Japanese was that two of the inmates, Arthur Hummel Jr [later the US Ambassador to China in the 1980s [41] and Laurie Tipton, a British man [42], escaped from the camp in early June, 1944 and were never recaptured. They had been planning their escape with the full assistance of Father De Jaegher [43] for more than 12 months but there were several postponements because of Japanese patrols, a full moon, or poor escape conditions. One night everything went well and away they went. I did not know any details at the time of their escape but I remember them arriving back at the camp shortly after our liberation.

[41] Article in The Atlanta Journal and Constitution dated August 9, 1981, page 22-A. A copy is Family document. Bradbury family collection. Hummel was born in China of American missionary parents. He was teaching in a Peking school at the time of Pearl Harbor. After his escape, Hummel and Tipton joined Chinese guerilla forces fighting the Japanese. Tipton was a tobacco company executive.

Father Raymond De Jaegher outlined the preparations for the escape in his book: "The Enemy Within".

Father De Jaegher's "First Letter Home - X'Mas 1945" ... [click here]

In March 2000, Mr Hummel confirmed the date of the escape and his subsequent activities with Tipton until the camp was liberated in a personal conversation.

[42] Laurie Tipton's Book: "Chinese Escapade" ... [click here]

[43] The original two escapees were to be Tipton and De Jaegher. A fellow priest told De Jaegher his role should be to remain in the camp because he was the camp's best intelligence gathering operator. De Jaegher's place in the escape was taken by Hummel, who volunteered for the job.

When Mr Hummel and Mr Tipton arrived back at the camp, they were given heroes' welcomes and carried shoulder-high by the inmates. I listened avidly to the tale of their escape from the time when they further darkened their heavily tanned faces and wore long Chinese gowns to look like Chinese. After escaping from the camp, they met some Chinese Nationalist guerrillas by arrangement who hurried them away and hid them. Their escape aim was to contact Chungking (now called Chongqing), which was then the seat of the Chinese Nationalist Government in unoccupied China, so that the western Allied forces could be informed of deteriorating prison conditions because it was believed the Allied forces had no recent knowledge of our plight. Mr Hummel and Mr Tipton told us how they spoke by radio to Chinese Army authorities in Chungking, which was also the headquarters for the Allied forces seeking to liberate China from the Japanese. The United States authorities obviously became concerned about our conditions in the camp because we were rescued by American soldiers two days after the war ended. We were very glad to be so quickly rescued because the Japanese always told us we were going to be killed whether Japan lost or won the war.

It was always in the back of my mind that we may be shot. I am convinced that had the Japanese main islands or our part of China been invaded by the Allies, we would have been shot without hesitation. As it was, the sudden unexpected capitulation of Japan prevented this. I was always frightened of the machine-guns on the walls. They used to point at us and I never knew whether they would shoot us because the guards often said they would if the war ever went against them. I remember saying to my mother on one occasion: "I think they're going to kill us this time" and I thought to myself: "I'm only young, there's so many things I want to do before I die and now I won't be able to." Thankfully, they did not fire. I did not regard the guards' threats as idle talk at the time and I still don't. When you have a gun pointing at you, you tend to listen carefully to what is said.

Between June 1944 and our liberation on August 17, 1945, Mr Hummel and Mr Tipton served alongside Chinese Nationalist forces in Shantung Province and regularly communicated with Father De Jaegher in the camp using Father De Jaegher's messaging system. They sent news of the war and helped arrange for the urgently needed medical drugs smuggled into the camp hidden in Red Cross parcels.

Part of the story told to cover up Hummel's and Tipton's escape was that they were in the camp toilets during head counts but the camp management committee, to prevent reprisals, reported them missing the day after they escaped. Our food ration was withheld for a day or two after the escape.

From then, the Japanese were especially alert to prevent escapes and stopped any inmate out of his room after dark. For instance, my elderly uncle Edward was heading for the toilets one night when he was challenged by an irate Japanese guard who stuck his rifle into his stomach and demanded in Japanese to know where he was going. Edward expected nervously to be shot because he couldn't remember the Japanese name for toilet. He knew that it was similar in sound to a stringed musical instrument and he went through: guitar, ukulele before he hit upon the correct one, banjo. Benjo is Japanese for toilet. Although the common language used by the inmates to the Japanese was Chinese, we were expected to know some Japanese terms.

The toilets could be dangerous for other reasons. Father Keymolen was a young priest with an unfortunately misshapen back. One night on the way to the toilets he fell into a cesspit and could not get himself out. He had to be rescued after calling for help. For the rest of the war the other inmates ribbed him about this.

The camp was infested with all sorts of vermin. There were rats, bedbugs, scorpions and mosquitoes. I don't remember flies but there must have been because I remember maggots in the horsemeat. We spent lots of time trying to eliminate the vermin by making and setting traps. Competitions were run among the young men to win a prize for the one who caught the most rats. The prize was 12 smuggled hen eggs. Unfortunately when one winner went to cook one he found it to be rotten. So were the other 11.

There was a stone church building in the camp which the inmates used for talks, study and recreation. We had amateur concerts in there and some plays. I can remember singing a solo song in a concert. The song was called `Daddy wouldn't buy me a bow wow.' Letitia Metcalfe and I also sang `September in the rain.' This concert was written and produced by Letitia's stepfather Gerald Thomas, a Tientsin businessman who concert-billed himself as ‘Professor Thomas and his Stewdents.'

Church services of various denominations were held each Sunday in the church, including Catholic, Church of England and others. I was in the choir at the Catholic service and most of us went to the other church services as well. The different ministers of religion used to attend the services of other denominations. One of the Church of England ministers used to knit scarves during the Catholic services. He used to sit up the back of the church and I asked him once: "What are you doing here?" and he said: "Oh, I attend all the services."

There was a rainbow of religious beliefs among the inmates ― from Christianity to Judaism, from Judaism to Bhuddism, from Bhuddism to atheism. If the inmates of Wei-Hsien had set up a university theological campus during our imprisonment, it would possibly have had the most distinguished group of teachers of theology assembled anywhere in the world at that time.

We all lived together and helped each other. Nobody thought it strange for different religions to mix together in church. After all, we mixed together in every-day life in the camp so it was natural to mix together at worship. The church and the dining room were used for school rooms during the day but we had to vacate the dining room for lunch to be served.

I had boyfriends for a while and then they either got sick of me or I got sick of them. There were plenty of young men there but I used to select those who were interesting and had personality. I don't remember how many boyfriends I had those days but I don't think I really loved any. I found it was good to be with someone who cared and was willing to sit and talk. There were no drugs that I am aware of and alcohol was a no-no for teenage girls. Everybody warned us what happened to girls who drank alcohol. And, sex was just not a thing we thought about. That was our training and upbringing ― especially for convent-educated girls.

Towards the second half of 1945, I began giving up my belief that we would leave the camp and escape its monotony. The Japanese guards never seemed to worry about the way the war was going for them and maintained their vigilance over us. Every day there was the roll call and occasionally roll calls in the middle of the night. I suppose we got into a routine and only dreamed about obtaining our freedom. The most important things I thought about in camp were getting a square meal and being free to do what I liked within the bounds of my upbringing [44].

[44] Readers now wanting another view of Wei-Hsien seen through the eyes of a woman who was there until August 1943 when she was repatriated back to the US, are invited to read Chapter 14 – Another view of Wei-Hsien – before reading the next chapter. The chapter includes extracts from a report given to the US State Department in December 1943.

#

Japanese guard post at the camp. Done by fellow prisoner.

Photograph: Georgie Perry

[click here]

Father De Jaegher played a key role in organising the only escape from the camp, and was a significant adviser to the camp's management committee in general matters of dealing with the Japanese. As the Allies' war progressed against the Japanese, Father De Jaegher noted a decline in the guards' morale. He advised the committee on how to treat with Chinese Communist-led forces. These forces, towards the end of the war, began encircling the Wei-Hsien area. His advice to the committee possibly averted a massacre of the camp's inmates.

He recommended the camp leaders not to provoke a revolt by the camp's inmates as suggested by the Chinese Communists in a secret communication to the camp. He warned a camp revolt could lead to the gathering Communist forces – who were no friends of non-Chinese (contained in the camp) and the Japanese guards – massacring both the inmates and the Japanese. He counselled that the camp patiently wait for Allied liberation. His suggested strategy was accepted by the camp's leaders.

They were guided in that decision by Father De Jaegher and others analysing the information they were gathering from secret radio monitoring and incoming documentation being brought in secret messages by the Chinese toilet coolies [see text]. His advice was later proven to be well-founded. In the last days of the repatriation of liberated internees from the camp, Communist forces blew up the key Wei-Hsien railway infrastructure. This forced the Allied forces to fly out the last remaining Wei-Hsien internees.

Post-war, Father De Jaegher again largely worked in Asia. He became internationally famous as an anti-Communist campaigner and prominent as an adviser to the largely Catholic-led, anti-Communist leadership of South Vietnam. This country was formed in the mid-1950s following the 1954 collapse of French-led forces to Vietnamese Communist forces. A partitioned Vietnam into south and north sectors then followed as a result of international talks. South Vietnam eventually fell in 1975 to Communist forces, despite protracted and considerable military and financial support from the US and other countries including: South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand. This Viet Cong success led to the reunification of Vietnam from South and North Vietnams into present-day Vietnam, a Communist state.

See also Further Reading.

A pressed flower from the prison given to me when sick.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

See also Further reading.

According to my calculations, the race was run over a distance of about 800 metres. This distance estimate is based on a detailed map of the camp prepared by the honorary Swiss Consul-General's representative, Mr V E Egger, who lived in Tsingtao.

During the war, Mr Egger also acted as the representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Mr Egger visited the camp on several occasions, bringing with him Red Cross supplies and money which was called comfort money. Inmates could apply for the money if they signed a promissory note undertaking to repay it after the war. Map copy is in Bradbury family collection. Mr Egger also issued in 1943 safekeeping receipts on Shanghai Swiss Consulate-General letterhead to my mother for personal jewellery she had brought to the camp and the title deeds to our Tsingtao home. The Swiss Government from late 1941 undertook to represent British interests in Japanese-occupied China.

Receipts are in Cooke family collection.

Father Raymond De Jaegher outlined the preparations for the escape in his book: "The Enemy Within".

Father De Jaegher's "First Letter Home - X'Mas 1945" ... [click here]

In March 2000, Mr Hummel confirmed the date of the escape and his subsequent activities with Tipton until the camp was liberated in a personal conversation.