THREE STAYED THERE, AN INTERLUDE

By: Dorothy Potter

If only I had heeded the gypsy's warning given to me way back in the Australian mountains in the year 1941, how very different my life during the latter years, and that of my husband and small son, would have been.

Wars, financial worries, yes and even famine were all foretold, but how could one take such fantastic tales seriously in the midst of a lively party of friends on a gorgeous autumn day in July?

We were spending the last few weeks of our furlough in Australia before leaving for Shanghai, in time for my husband to take up his duties with the Chinese Maritime Customs, in whose service he had been employed for over twenty years.

I'm glad we had such a carefree holiday, as it was a bright spot to look back upon in the coming troublesome years.

Our boat left Brisbane in the beginning of October, and the second day at sea our troubles commenced by Anthony developing measles. This meant our being confined to our cabins and missing the usual jolly time one had on board ship.

However, we were out of quarantine by the time the ship reached Manila and apart from a very rough passage for two days, we sailed into Hong Kong harbour without mishap.

What a marvellous sight, this fairyland harbour, especially in the early evening with the passing fishing junks with colourful sails of red, brown and blue and the gaudily painted eyes in the front of the boats. "No can see, no can savee," says John Chinaman and so he goes prepared, even to the fishing grounds.

Our boat sailed along into the main harbour with the towering hills guarding it and the fairy-lights, rows and rows of them, beginning to twinkle on the distant roads of the Peak. The water-front was already aglow with light. Naval craft, ocean ships and coastal craft with their strings of lights, added to the brilliance of the picture. It was a beautiful sight.

Hong-Kong harbour in 1920.

We were all packed up and ready to go ashore after the final passport examination by the Hong Kong police, a new formality since Britain had been at war.

When my turn came, the examining officer asked for my pass from Canberra, to permit landing in Hong Kong. As we knew nothing of this new regulation and had not been informed by the shipping company in Brisbane, I had to admit that I had no permit. The result, of course, was that I was not allowed to land and was told that I would have to return with Anthony to Australia on the same ship.

This was a great blow, but I felt it was useless to complain. Regulations are made to be kept, not broken. In great dejection, I unpacked my suitcases and put Anthony to bed. One other lady passenger was in the same fix. Like ourselves she was destined for Shanghai but had to land in Hong Kong to book a passage and remain there until she could get a ship. She stamped and raved and ended by completely losing her temper, but all to no purpose. Eventually we were the only two women left on board.

My husband tried to cheer me up by suggesting that he would chase around and hunt up people to try for a permit for me but I was not very hopeful.

I was leaning on the ship's rail, feeling very depressed, when the police officer tapped me on the shoulder. "I thought you were a real brick," he said, "over your disappointment, so I'm going ashore to see what can be done about it. I'll let you know in the morning." With this feeling of "friends at court" I went to bed in a happier frame of mind. True to his word, a permit arrived and was delivered to my cabin before breakfast. This was followed by two others, one from my husband and the other from friends there. I lost no time in getting ashore lest new regulations came into being!

During my time there, very few women were actually supposed to be in the Colony. In fact, only those doing absolutely essential work were allowed to be there but quite a few had by various means filtered back, thinking that after all there was no war coming off with Japan. There must have been several hundred women in Kowloon and Hong Kong when I passed through. Husbands were holding indignation meetings and writing to the press in their effort to force the government's hand. Nineteen divorce cases were pending in the courts that week alone and altogether, everyone seemed thoroughly disgruntled. I often wondered how they all felt when the Japs did arrive!

After a week of parties, trips around and shopping, we left for Shanghai by coastal steamer, arriving there on the 28th October to find instructions that my husband had been transferred to Tientsin.

Really, it seemed as though the hoodoo had got a good grip, as this meant giving up our furnished flat in Shanghai and selling everything except necessities, undoubtedly at a good loss too, but the freight and packing costs for another thousand mile sea journey absolutely forbade any other course.

It was at this stage that my husband remarked "When I want really cheering up, I'll read a few chapters out of the Book of Job," but he little knew what frolicsome, evil spirits can do when they get really started.

After two hectic weeks of sorting and repacking interspersed with one or two lively interludes such as getting trapped in a burning shop in the celebrated Nanking Road and standing next to a young patriot who decided at that moment to send a collaborator to the "happy hunting grounds" with the aid of a well flung bomb, we found ourselves, one cold morning in November, on the Bund ready to sail up North.

Shanghai bund before WWII.

We had managed to cut down our essential baggage to 12 cases, containing our collection of curios and pictures together with our linen, cutlery and kitchen requisites. . Many of our friends were there on the wharf to see us depart and our cabin was filled with baskets of gorgeous flowers, the traditional parting gift in the Far East.

With the good wishes, of our friends still ringing in our ears, we steamed down the Whangpu River and past the huge buildings on the Bund, Custom House, Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, the new premises of the Bank of China, a delightful combination of the old Chinese and modern style of architecture, next the Garden Bridge over the. Soochow Creek where the smaller junks and sampams congest that narrow waterway, filled to overflowing by the crews and their families, and the huge mass of the Broadway Mansions, an ultra-modern apartment building, towering behind, then past the oil installations until by devious twists and turns the vessel finally arrived at Woosung and the open sea.

I don't remember much of the next two days as the China coast is none too kind to poor sea travellers, but when we anchored at Chefoo we were inundated with Japanese officials of the customs and gendarmes, all equally unpleasant. They insisted that the Captain order the stewards to bring them tea, soft drinks and cigarettes. None but the best brands were acceptable to them. They monopolized the 1st class saloon to the exclusion of the passengers and sprawled with feet on tables or as the fancy suited. They bawled, laughed and spat to their hearts content, a law unto themselves.

A few of these so called Customs officials searched the ship and later when going into my cabin I found one of them interesting himself in one of my suitcases. I was more than annoyed and told him a few home truths and finally that my husband was an employee of the Customs. On receipt of this information, he bowed from the waist down and hissed what appeared to be an apology. We were later approached with the offer of a launch in case we needed to go ashore. We tactfully declined. If the port officials' attitude on the ship was anything to go by, we had no intention of doubling the dose.

Coastal steamer, the SS Ting Sang

https://industrialhistoryhk.org/the-ting-sang-first-owner-indo-china-steam-navigation-co-ltd/

Our next encounter with these overbearing gentry was when we landed at Tangku at the entrance of the Haiho River to Tientsin. As before, the Japanese boarded the boat and issued instructions that we were to queue up outside on the deck with our passports, other documents and hand baggage. It was a bitterly cold morning and there was absolutely no reason why passports examination could not have taken place in the saloon, but officialdom was out to be cussed and cussed it was. I admired the Captain of our boat for the way he kept his temper under control. It must have been a stupendous effort. Steerage 3rd class passengers and the Chinese crew preceded the 1st class passengers, and the Captain came last! Our tempers were decidedly frayed when the ordeal was over. The usual nonsensical printed questionnaire had to be answered, "Where were you born? Who was your grandfather? Where did you go to school?" I thought the young gentleman who completed the school question by inserting the name of that well known reform school, Borstal, was looking for trouble!

At 3 o'clock we were gracefully permitted to board the launch for the long trip up the river to Tientsin. We arrived there late in the evening and disembarked on the Bund of the British Concession into a barbed wire cage arrangement for a further interrogation by the Japanese military and gendarmerie. The signs and portents we thought, were none too favourable.

At 3 o'clock we were gracefully permitted to board the launch for the long trip up the river to Tientsin. We arrived there late in the evening and disembarked on the Bund of the British Concession into a barbed wire cage arrangement for a further interrogation by the Japanese military and gendarmerie. The signs and portents we thought, were none too favourable.

The next week was spent in house hunting and, eventually we managed to rent a partly furnished place and had bought sufficient carpets and furniture for our needs. We then proceeded to unpack the cases brought from Shanghai. Imagine my horror in finding everything smashed to smithereens. The cases must have been thrown on to the launch to produce such results. When the servants finished emptying the fragments on to the floor, I just stood by my treasures and wept. Apart from never being able to replace lots of them, china and glass was very expensive at the time and difficult to get.

I had managed to get some very good Chinese servants, so we settled down to a normal life once more ...... so we thought!

My husband commenced his duties at the Custom House and Anthony started in the kindergarten at the British Grammar School.

America at War with Japan !

But alas, this peaceful existence was very short-lived. On the morning of December 8, Jim went off to the office and Amah took Anthony to school, but in less than half an hour Jim was back again, very perturbed as the Custom House was surrounded by Japanese soldiers who would not allow him to pass. A few minutes later the amah came in looking very worried. She said she had put the young master in school and when she came out, plenty of Japanese soldiers were around the school. I scampered out of the house in search of a rickshaw to take me to the school and arriving there found my entry blocked by sentries with fixed bayonets. By his time, a number of anxious parents had congregated around the main entrance, but attempts to enter the school were thwarted. About noon a Japanese officer drove up in a car and I requested his permission to remove my small son. He just nodded and replied in pidgin English "can do." Before he had time to repent, I raced up the drive and into the school, grabbed Anthony and bolted outside.

The older pupils were kept there until after 5 p.m. What for, nobody knew, and I doubt very much whether the Japs knew themselves. The school was later commandeered as a military headquarters.

By the time I got home, a number of friends had dropped in to discuss the situation. We knew by that time we were at war with Japan. The news of Pearl Harbour had also got through but we pooh-poohed it. We were as yet unused to the mental process of "sifting the grain from the chaff," but we had plenty of time in which to learn!

We were all a trifle dazed by the turn of events and were busy discussing probabilities when a friend dashed in to say that a Jap military truck had driven up to the house and her husband had been taken away but where she didn't know. It was not until three weeks later that we tracked him down in a former municipal gaol where he was confined in a cell usually reserved for hardened criminals. There were a number of other men beside our own Nationals. The gaol was without any form of heating and with the outside temperature below freezing point, they suffered miserably from the cold besides other indignities. They were released after a period of about six weeks but were compelled to sign a statement saying that they had been decently treated.

We realized by the manner of these arrests that the Japanese must have planned very well in advance and a very comprehensive black-list existed of those not in good odour. The British Commissioner of the Tientsin Customs was arrested and conveyed to a Chinese gaol in Peking. He had a particularly trying time. The head of the Municipal police and the manager of the leading American oil company were also arrested and gaoled. The bulk of our own nationals were confined in the old American Marine barracks on the Racecourse Road.

For some unknown reason, my husband's name and those of three other colleagues must have been omitted from the list, as they were not molested in any way. To this day, we cannot think how or why they escaped prison. The mental worry however was very bad in spite of the liberty they enjoyed. Every day, the Japs entered the house under all sorts of specious pretexts, either from the front entrance or the rear, and one never knew whether that particular interview would end up by his being escorted to gaol. A suitcase was always kept packed for such an eventuality.

For some unknown reason, my husband's name and those of three other colleagues must have been omitted from the list, as they were not molested in any way. To this day, we cannot think how or why they escaped prison. The mental worry however was very bad in spite of the liberty they enjoyed. Every day, the Japs entered the house under all sorts of specious pretexts, either from the front entrance or the rear, and one never knew whether that particular interview would end up by his being escorted to gaol. A suitcase was always kept packed for such an eventuality.

The only other incident on the first day was when two Japanese soldiers marched into the house demanding to see the radio. We took them into the drawing room and showed them our Marconi . This was sealed by pasting a flimsy strip of paper across the control knob. This strip could be gently eased off when we felt it was comparatively safe to listen in, but later we found it too risky and had to desist though the temptation to listen was very hard to resist. On reflection it was perhaps as well that we could not hear the news. It was not particularly cheerful in the earlier phases and we might not have been as cheerful as we tried to be. But however bad things appeared to be, we kept our faith in our own people and their allies. Nothing shook our conviction, whatever happened, that we could win out in the struggle. The possibility of our losing never entered into our heads.

Another particular cause of anxiety was an old radio-gramophone belonging to the previous tenant. By appearance, it must have been one of the very first of these machines on the market. The back was open, revealing a wondrous assortment of wires, valves, transformer units and the various gadgets making up the contraption. The wave length was found by moving a wooden knob along a marked scale. It never uttered a squeak during our tenancy but functioned as a plant stand. It must have been reported on during the sealing of the Marconi, for one day, whilst I was alone. in marched a Japanese officer and two soldiers with fixed bayonets. He stationed these two at the door of the room, then shouted to me in English demanding to see the machine and to know where I had sent messages. In vain I tried to explain that it was not a transmitter, but to no apparent purpose. Oh! wasn't I glad when my husband came in. Somehow he had a way with Japs as he generally managed to calm them down. He fetched out drinks and sent to the kitchen for tea for the sentries.

... very old Radio !

Gradually the tension seemed to lessen and he got down to the job of persuading the officer to believe in the uselessness of the object under suspicion. Things seemed much easier when we offered to surrender it for their examination. Our only desire was to get the beastly box of tricks out of the house. They left shortly afterwards, but apparently not fully satisfied as a number of so called experts pestered us during the following week for continued probes in the innards of the machine. In the end it was removed with the Marconi and we breathed easier.

Our first big problem was money as we had only a few local dollars in hand, intending to go to the bank on Monday. But the first thing the Japs did was to take over the banks, hotels and all British and American administration buildings. Luckily for us the next door neighbour happened to have a surplus of cash on hand and loaned us fifteen hundred dollars. I immediately called the servants and paid their monthly wages and asked them what they intended to do as we could no longer afford to employ them. Cook and amah decided to return to the country but the boy decided that he would like to remain with us as long as we could provide him with food. He was not interested in the wages as he fully understood our position. I was very touched by this and so he stayed and shared equally with us whatever we had. I taught him to cook and we had a fifty-fifty sort of arrangement which worked very well.

... British armband issued by the Japs !

The Japs issued us with bright red arm bands on which were stamped the two Chinese characters "Ying-kuo" meaning British or more correctly, English national . These bands had to be worn on all occasions under threats of dire penalties. No more than three of us were now allowed to congregate in the streets at a time.

We could shop in the Concession, but only in certain places. Orders were issued concerning blackout arrangements in case of air raids. A large earthenware jar containing water had to be placed outside the front gate in case of consequent fire. This was a source of amusement to us as immediately it was placed outside, the water froze solid.

English road and shop signs were removed and replaced with those bearing Chinese characters. The use of the English language was forbidden when addressing shopkeepers or our servants. This order was honoured in the breach.

... British flag over Gordon Hall - Tientsin. !

An amusing incident happened about this time during a public ceremony of raising the Japanese and puppet regime flag on the former Gordon Hall. Thousands of Chinese were watching the event. They dearly loved a show of this sort. The military forces were called smartly to attention and Wang-keh-Ming, the head of the puppet regime walked forward to pull the string. For some unknown reason the flags stuck. Wang tugged harder and flapped wildly with the rope. There was an ominous crack and down cascaded a shower of tiles on his head, knocking him senseless to the ground. He was borne to his car to the cries of "ai-yah" from the surrounding crowd. To the Chinese present, it was a very bad omen.

Another amusing angle concerning the denial of the English language was the fact that the Japanese in the meetings with their Axis partners, the Germans and the Italians, had to resort to the forbidden tongue in order to be understood. This was told to me by a German journalist whilst I was on a visit to some neutral friends. A very important Japanese General was to visit Tientsin, so it was agreed by the Japanese authorities to throw a party in his honour, inviting all the noted German and Italian residents together with their wives. The party was to be held in the Astor Hotel (formerly owned by the British). On the night in question a silver shield was presented to the General and a huge basket of flowers to his wife. After dinner the General stood up to thank everyone and he spoke in broken English as very few folk understood Japanese. "Ladies and Gentleman I wish to thank you from the bottom of my heart," and with a beaming smile towards his wife continued, "and also from my wife's bottom."

Periodically we were made to attend the Gordon Hall, the former Municipal Offices of the concession, for interrogation concerning our financial resources, property, and such other information as suited our gaolers. All sorts of ridiculous questions were asked such as how many coats or pants we possessed and not forgetting the old chestnut of grandfather's origin, which by this time had begun to pall. The whole thing from our point of view was meaningless and was meant possibly as a form of irritation. It succeeded admirably if this was the intention.

Vaccination and inoculation were also compulsory, usually at intervals of 3 months. Japanese-made serums and vaccines were issued to the small temporary British hospital and administered by our own doctors. For that we were particularly grateful although we had some misgivings on the standards of the Jap products.

This sort of life went on for about 15 months with all of us trying to live as normal a life as possible under tiring circumstances. The schools were closed and eventually our church. The last mentioned as the altar was desecrated by some Japanese soldiers. It had been used as a lavatory. We held small services in several private houses by dodging the sentries. On entering or leaving, we limited numbers to two persons only. Others followed at intervals.

All this came to an end in March 1942 when we received orders to pack ready for a concentration camp situated at Weihsien in Shantung province. We were instructed that we could take one bed, one trunk and one suitcase each. Children were not included in their calculations. Parents had to cram in what they could for their use. On no account was anything to be packed into beds. We then began the hectic planning of what to and what not to take.

On the evening of March 29th we left our home after handing the keys to a waiting gendarme who took possession of everything we owned other than those few things we were carrying with us. That was the last we saw of everything we had accumulated during our twenty years in China.

... Brian and his parents on their way to Weihsien !

It was a bitterly cold evening and we had to wait outside the old Volunteer Drill Hall to have our suitcases examined by the Jap guards who just tipped everything out on the dirty ground. They poked into our pitiful belongings, emptied thermos bottles, trampled on packages of foodstuffs under the pretext that it was not necessary, confiscated scissors and any knives they found and generally made themselves as obnoxious as possible. We were then ordered to repack our cases and be ready for the march to the railway station, about two miles away, by nine o'clock.

Old people and babies were graciously allowed to ride in rickshaws, providing of course, that one had funds enough in hand to pay for them. The rest had to march through the streets lined with grinning Chinese, German and Italian nationals. If it was the intention here to humble our pride, it failed miserably. We had no intention of allowing that, least of all to the Japanese. Most of us adopted a don't-care-a-damn attitude and ignored the grinning array of faces at the kerbsides.

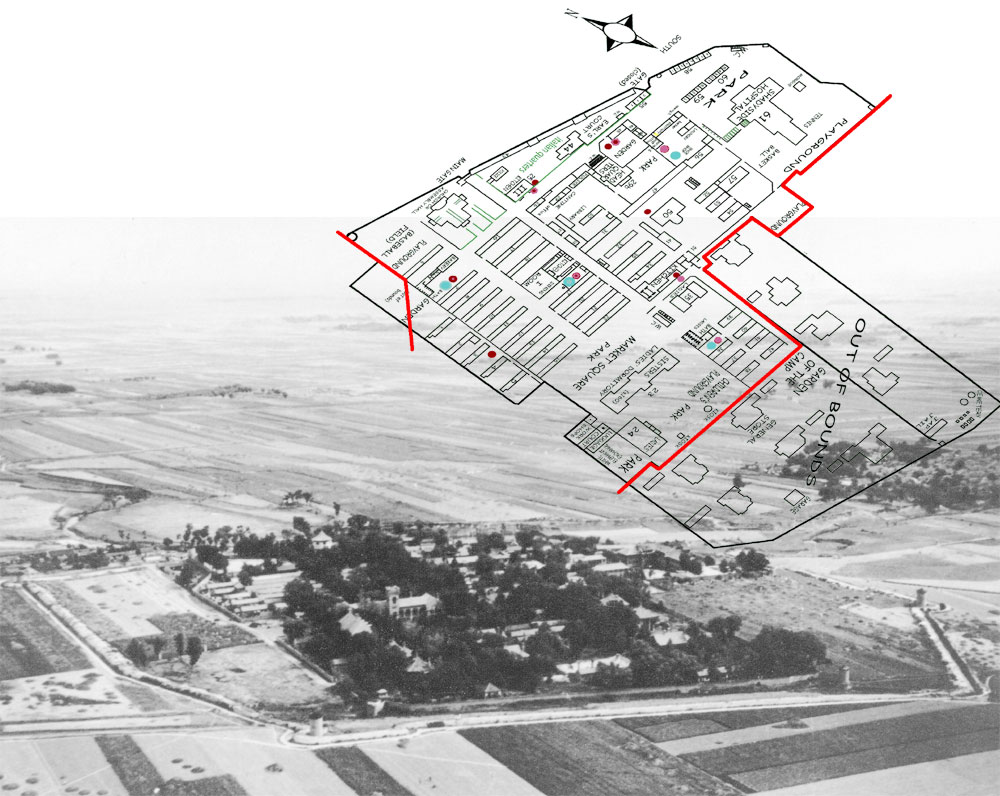

We arrived at the station around eleven o'clock and stood there until midnight when we were bundled unceremoniously into coolie trucks on the train. A disgusting toilet was at the end of our compartment. Accommodation was strained to bursting point. It was beyond the bounds of possibility to try to move about, so we sat cramped together for two nights and a day before the train crawled into Weihsien. It was a nightmare journey to say the very least of it and we arrived in an exhausted condition. It was with a sense of relief that we arrived at the camp, a series of compounds, roughly in all about forty acres in extent.

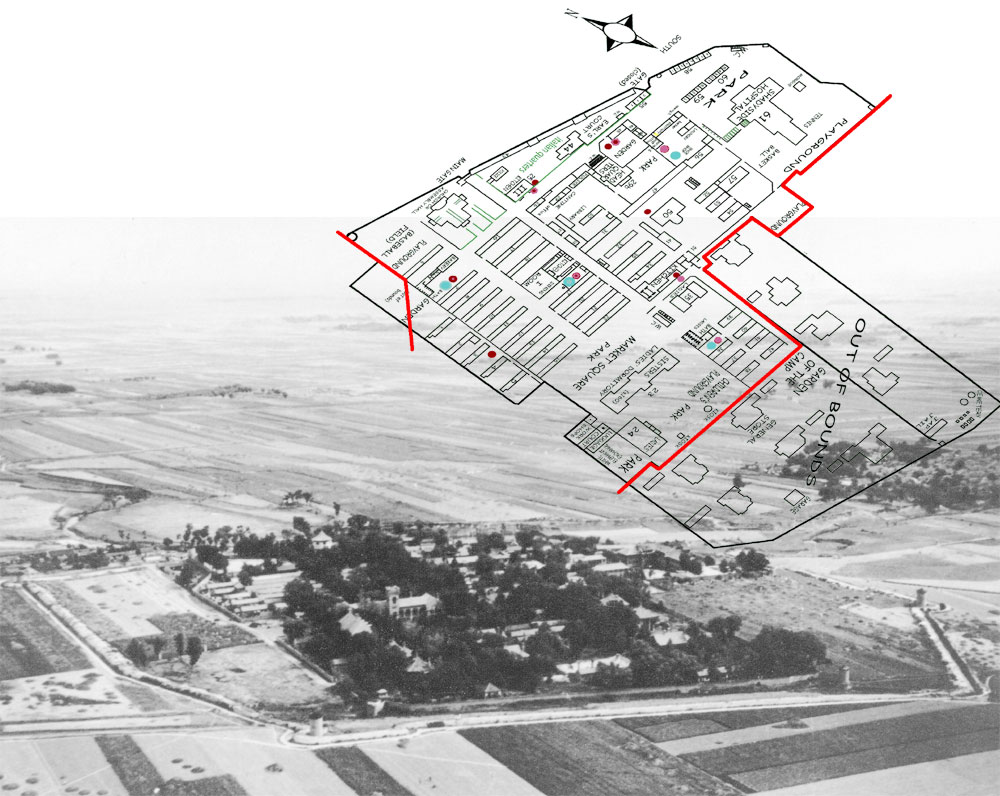

... entrance to the Weihsien Compound

It was owned by American Presbyterian Mission and formerly used as a missionary training centre for Chinese students. It had a brilliant red gate and high surrounding walls and could accommodate the two thousand odd POW's who eventually were interned there. It suited the Japs admirably for the purpose they had in mind.

A number of our Peking friends who were already there were waiting to welcome us.

We were conducted to our room which was one in a row of six formerly housing a couple of Chinese students. The overall size was twelve by eight and a half feet. For three of us it was rather a tight squeeze but we managed in the time we spent there to find a modicum of comfort in the space at our disposal. The room was absolutely empty, of course, and as our beds had not arrived our first effort was to procure, if possible, some sort of bedding. Two travelling rugs, a deck chair in dubious state of repair and some odd bits of straw matting made up our final collection. It was straining the resources of our friends to provide even this; We managed this way for a fortnight until our beds arrived. We welcomed them with open arms. The floor was wet with snow and we were aching in every bone as we arose after those fitful nights.

The camp was planned in rows of these small rooms, whilst the larger buildings in the campus were for lecture and administrative purposes. There were 3 large kitchens and dining halls, the kitchens being equipped solely with large cauldrons for the cooking of the usual type of coolie Chinese food. This was the only means provided. Sanitary arrangements bordered on the primitive, consisting of cubicles fitted with oblong porcelain bowls sunk into cement floor. The cess-pool was periodically emptied by coolies but the rest of the cleaning had to be performed by the internees, a job we all loathed and detested. A roster was kept of the under 60's who had the odious duty to perform for a week in rotation. Marvellous inducements in the way of precious tins of coffee were handed out by individuals to those less finicky who were willing to "stand-in" for the detested job.

It was very amusing during the first week or so to see folks furtively creeping out of their rooms in the early morning to empty chamber pots without being observed, but later on the requisite duty fell into perspective and nobody bothered at all about it.

There were a number of different nationalities in the camp, American, British, Dutch, Belgian, Greeks, Norwegian and White Russian. The latter mentioned were employees of the former British Municipal Council and were in possession of British protective passports. Later on when Italy turned over to the Allies, a number of Italians were housed on the far side of the camp, but it was a very long time before any contact with them was permitted.

Life was very chaotic in the first few days. The cooking arrangements and the meals were horrible. We seemed to live on bread porridge for the early meal and a thin watery fluid called leek soup for the mid-day and evening meal. This so-called soup consisted of a few chopped leeks floating around in water.

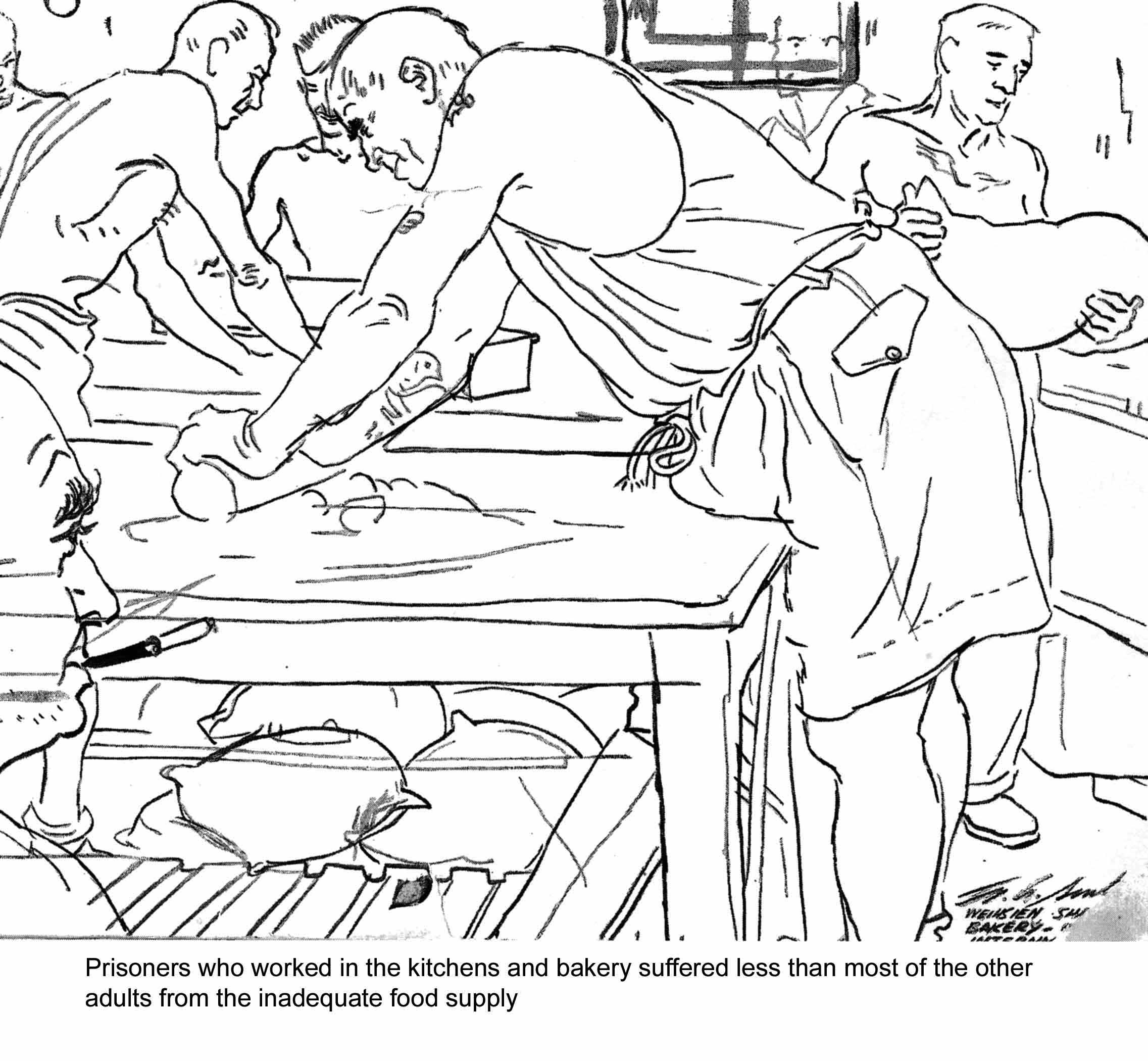

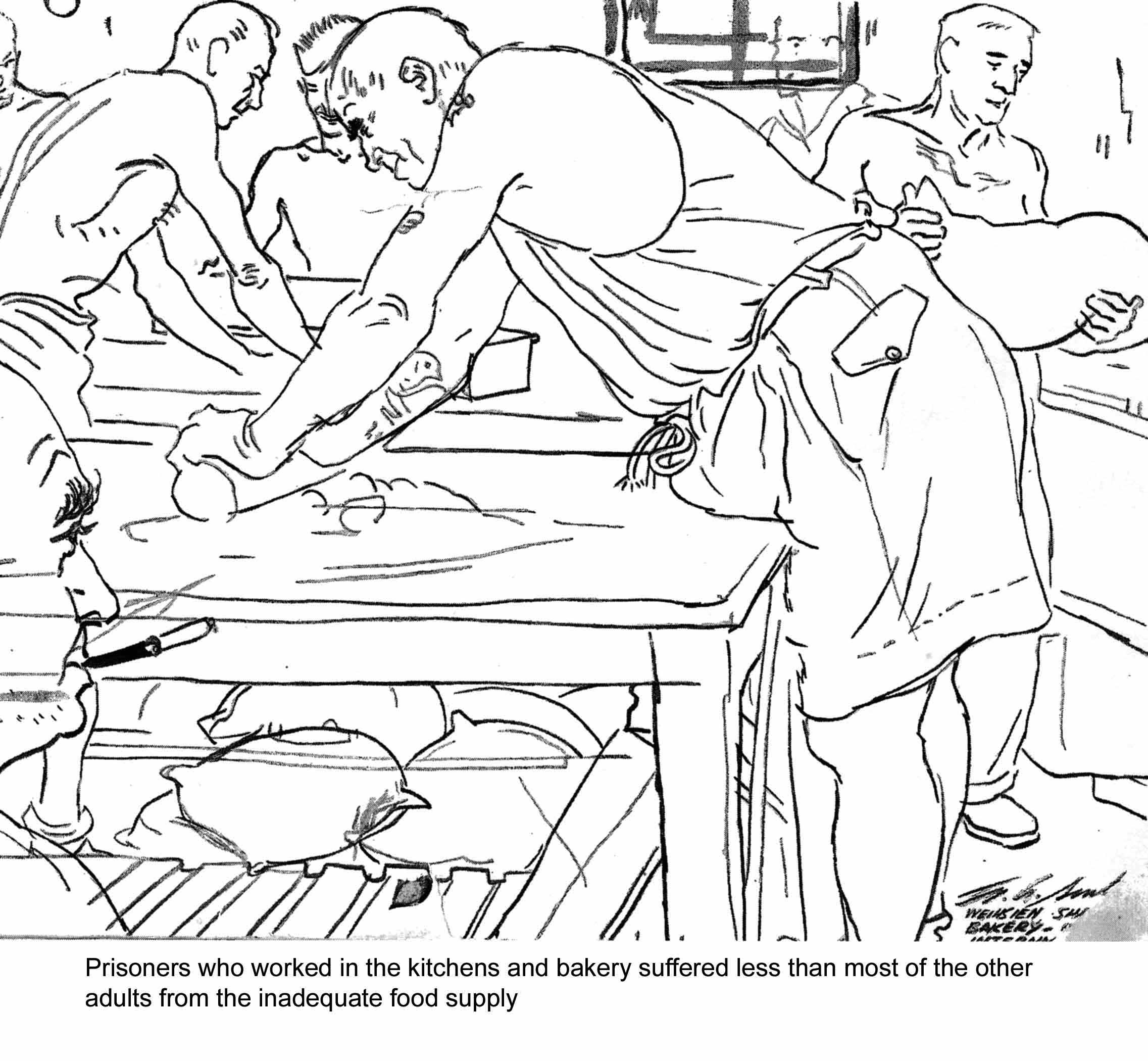

... Kitchen #1

This situation was mercifully relieved by the Catholic fathers. Incidentally there were over five hundred of them in camp, including five Bishops. In the various catholic institutions they had been used to this sort of bulk cooking in primitive style and they nobly stepped into the breach. They organized and trained teams of cooks who were therefore able to make the best of the very poor and meagre food the Japanese doled out to us. By the time the fathers left the camp, about sixteen months later, the trained kitchen staffs were turning out quite creditable meals and were able to adequately disguise such doubtful comestibles as buffalo, camel, horse and mule meat. Not that it was donated in quantity. The amounts were pitifully slim for the numbers to cater for. The difficulties they had to cope with were stupendous. No proper utensils, flies by the million, no refrigeration and the poorest and most miserable vegetables the Japs could gouge out of the local peasantry without payment at all. Improvisation with all sorts of materials was really wonderful. We had a veterinary surgeon among the internees who examined the meat ration daily when it arrived. Coming from Tsingtao in ordinary rail cars without refrigeration, it was never more than what can be described as doubtful. The "very doubtful" was cut away and buried and the "possible" put on to cook immediately. Fish was always buried at once. It had to be accepted as rations but it went quickly under ground. Usually it brooked no delay.

Vegetables usually consisted of those not particularly alluring to the occidental palate such as sweet potatoes, which most of us grew to loathe, squash, field cucumbers, egg plant, huge Chinese winter radishes coarse and as tough as a boot, water reeds and some weird and wonderful weeds including clover, which they gave us when other greens were not available. The missionary body discussed the vitamin content of these "funnies" but we remained unimpressed.

Fat of any kind had practically disappeared from our diet, and sugar was a commodity we seemed to remember vaguely from some years ago. We were able periodically to purchase at the canteen a form of syrupy maltose which went under the Chinese name of "Tong Shih." It was a wonderful experience to get a taste of this, providing, of course, one had enough "comfort money" to pay for it.

There was one blessing we were always devoutly thankful for, our bread. The supply, if not particularly generous to hungry youngsters, was adequate. We saved any spare and turned it into rusks and stored them in a pillow case hung on the wall. Periodically they would be gone over and re-toasted. We felt that we had a reserve of food if things somehow went wrong.

It was soon realised that some sort of camp organisation would have to be inaugurated and a system was arranged which I think reflected great credit on those concerned. Nine chairmen were chosen with their committees. They went under the names of General Affairs, Discipline, Quarters, Education, Hospital Management, etc. These chairmen, besides heading their respective committees, were in contact with the Japanese Commandant and the Chief of Police, who of course was a member of the gendarmerie. This police head, likewise his top sergeant was an obnoxious official. They were known respectively as "King Kong" and "P'u-Shing-T'i," the latter being roughly translated from the Chinese as "No can do." The sergeant's Chinese vocabulary was limited to this one expression which he rode to death. There was no wholesale brutality in the camp mainly, I think, for the simple reason that it was well run by our own people and the Japs were content to leave well alone and were out to run it this way without recourse to undue pressure. One or two faces were smacked and usually for a definite and deserved reason. Had the position been reversed I do not think for one moment that we would have stood for half the amount the Japs did.

Roll Call

We did, however, have rather a tough time when two men escaped over the wall and got away on ponies already waiting for them. The committee had of course to eventually break the news to the Chief of Police, not before a few hours had elapsed to give the fugitives good and sufficient time to show a clean pair of heels. The Chief all but had an apoplectic seizure when they told him. His face went scarlet and he raved and stormed and regarded it as a personal affront. In consequence, regulations were tightened up in every way and roll calls and more roll calls were our affliction for months to come. it was no unusual thing to hold a roll call in the middle of the night. Everyone had to go out or be carried out to be counted. Even small babies and old people had to be produced for the head count and it often meant hours standing in the bitterly cold weather until the Japs were satisfied that no further escapes had taken place.

We had a team of British and American doctors, fellow internees in the camp and the work they did during our long stay was a marvellous example of courage, initiative and unselfishness.

The hospital which could later accommodate twenty-six bed patients, when it was first taken over by the internees was a bare shell . To the eternal discredit of the Japanese they contributed nothing at all, either in drugs or equipment, to what was eventually an excellent hospital with very creditably appointed surgical, medical, dental and eye clinics, besides operating theatre, laboratories, diet kitchens and other offices and wards. The Japanese were very quick to seize the opportunity, which was never denied them, of using the clinics for their own sick.

The Hospital is the three storey building at the upper right of the photo ! The Jail is just in front and on the left edge is Block-23 with the bell-tower.

Our supply of drugs, instruments and dressings was due to the foresight of these doctors who, when the internees were packing to go to camp, were given two parcels to carry with them to form the nucleus of our supplies. Later on our supplies were augmented by purchases through the Swiss Consul but, throughout the camp, the Japanese contributed nothing at all. They were also very ready to seize the opportunity to show off the hospital to visiting big-wigs. We took these occasions very philosophically, but nevertheless there was an itching desire to kick them when they did so.

No water was laid on in the hospital. Our supplies of water had to be hand pumped from shallow surface wells into a main tank above. This was the system throughout the camp. Water for the hospital had therefore carried a good distance from the outside. An engineer internee set out to rectify this difficulty. Using old pipes found around the camp and old bedstead rails, he piped water not only to the ground kitchens but to the operating theatre and offices on the floor above.

Another difficulty he surmounted was the heating of the theatre in the winter. It was not possible, of course, to have any naked form of flame with the ether fumes during the operation. He devised a very satisfactory hot-air appliance worked from the basement below. It was great success. Undoubtedly it saved quite a number of lives.

The general health of the camp was maintained on a high level in spite of the conditions under which we existed. Our death rate kept time with the births, a happy sort of balance to charm our statisticians, but the advent of a new arrival always provided a fillip of excitement. Everyone had to view the baby as soon as the child was out of hospital and friends rallied round to hand out from their hoards such precious items as an ounce or two of sugar, etc. for the christening cake.

Weddings were of course the great events. Permission had to be obtained from the Japs before they could be solemnized. It was really wonderful how a few strips of mosquito netting plus a silk nightie could be converted into a ravishing wedding dress! Honeymoons had, of course, to be spent in camp, but there was always some kind hearted married couple who were willing to separate and go into the dormitory for a few days so the new couple could have their room.

The "Church/Assembly Hall" photo taken in 1908 by Erik Gustafson's father ©

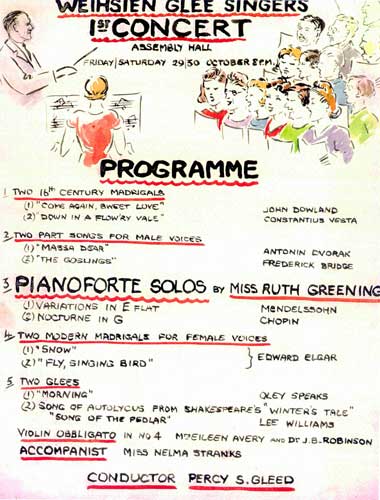

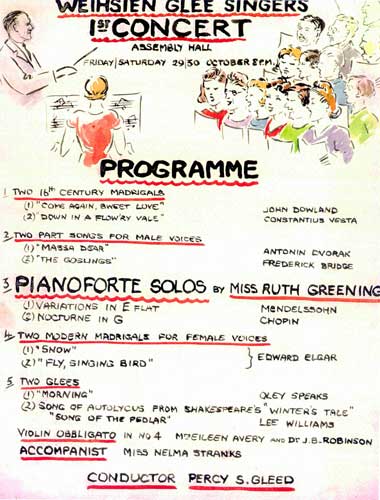

We were allowed the use of the church as an assembly hall during the week and many and varied were the activities held there. Meetings, Plays, Concerts, Piano Recitals, Orchestral Concerts and Exhibitions were given in the hall. It was always possible to gauge how things were going with the Japanese by their reactions following bad news. The hall lighting used to be their spite target. Invariably they would wait until the audience were nicely settled and the players ready, when the lights would suddenly fail.

Our camp electricians would be running around in circles in their efforts to locate the fault, but the main switch room it would be noted was invariably locked and not open to inspection.

One Good Friday the choral society of eighty members were singing the "Crucifixion" to a large and appreciative audience when without warning, out went the lights. Somehow or other it must have been generally suspected that the Japs intended to be awkward for, without further ado, each singer produced a tiny home-made peanut oil lamp and the programme continued without a further hitch. As a matter of fact, we all agreed that it was far more impressive this way and lost nothing by the Japs stupidity.

We all possessed one of these "home-spun" oil lamps. They were so useful when the Japs pulled off stunts like this or for use in the night when the camp lights were extinguished. We grudged however the oil being used this way as it often meant going without a piece of fried bread for breakfast, a very real denial. We were allowed to purchase the oil now and again in the canteen. It was not a ration.

One source of worry to us was the presence of the Chinese 8th Route, Communist Army in the vicinity. The Japs never succeeded in eliminating them in spite of the several serious attempts to do so. A favourite habit of these guerrillas was to catch the Jap sentries standing asleep against the trees in the camp. Then would they noiselessly climb down from the camp wall where they had been watching in the darkness and cut the sentry's throat. It was a terrifying sound at first to those living near the outer wall but we grew hardened and callous in time. On hearing this frozen scream we would slide out of bed and prop a trunk against the door lest the guerrilla, being chased, seek safety in our room and the Japs shoot it out with him, with ourselves inside. Not a pleasant thing to contemplate. We were rather afraid that the Japs would implicate us in these killings, but fortunately they never did.

Our Amateur Dramatic Society was most ambitious in the plays they produced. The scenic effects and the costumes were a marvel of ingenuity. The Japs always attended, whether they understood the piece or otherwise but were always puzzled to know where we obtained the materials. Bernard Shaw's "Androcles and the Lion" was staged with the lion outfit being produced from a moth eaten fur coat and pipe cleaners for whiskers. The armour for the Roman soldiers was made from "Spam" tins we gathered from our American friends.

We were also fortunate in having two very talented pianists, one being an Indian girl and the other an American gentleman. They gave us many very delightful recitals. Altogether, the entertainment side of camp life was very well catered for and was very much appreciated by all of us, particularly when it was remembered that every able bodied member of the camp had so many hours of community work to do and all practices had to be done in spare time.

My own job in camp was Captain of the Sewing Room. This high- sounding title was the result of an effort made by one or two of us, when we first arrived, to help the unattached men with their mending problem. It ended up as one of the best patronized efforts in the camp. We had a large room allocated to us. From various places we "scrounged," chairs, table for cutting, odd pairs of scissors and a small heating stove. Our staff grew from the modest beginnings to over twenty. Our job book at the end of camp showed a total of thirty thousand odd jobs that had been done. We had the assistance of one of the best British cutters in North China who came in the afternoons to cut out shorts, trousers, overalls, etc. from such strange sources of materials as chair covers, curtains, bedspreads and similar articles. We also kept the hospital stocked with sheets, O.P. towels, tea towels, etc.

Occasionally, the Japanese allowed us to have cheap materials and this was sold on a sort of lottery system.

Sometimes, the Jap guards came in for small jobs to be done. We hated doing anything for them but we had to weigh up the possibilities of repercussions on the camp if we refused. The committee were consulted and they were of this opinion so, now and again, when asked, we did so. I shall always remember one particular day when a fierce-looking guard marched into the sewing room and by pantomime efforts indicated that he had a hole in the seat of his trousers. I tried to make him understand that we would mend them if he brought them in. He promptly took them off and handed them to me. There were six workers in the room who were almost hysterical with suppressed laughter. He looked screamingly funny. The top half with his navy blue uniform coat with gold braid and long sword, the bottom half, long pink cotton pants. He marched solemnly backwards and forwards trailing his long sword until the job was completed. He then calmly put on his pants, bowed from the waist and went out. Ten minutes later he returned bearing a huge watermelon which he presented to me. As it was the first fruit we had tasted for many a month we stifled any compunction we may have had and enjoyed it thoroughly.

m/v Gripsholm arriving in New York - December 1943.

After about eight months the Jap commandant notified the committee that a number of American and Canadian internees were to be repatriated in exchange for Japanese prisoners of war. When the day of departure came we all congregated near the main gateway and gave them a wonderful send off but felt rather sad at being left behind.

By this time, the quantity and quality of the food supplied to us had begun to deteriorate badly and many were the attempts made to purchase food over the wall from the Chinese villagers. These activities passed under the name of black marketing but our activities in this direction hardly agreed with the accepted meaning of the term. We were merely out to supplement a semi- starvation diet by means of purchase, whether it was considered illegal or otherwise. Needless to remark, these activities were severely frowned on by the Japs who confiscated any goods found and gaoled the offender. In spite of these deterrents, the trade carried on briskly. Prices of course were extortionate but money has little meaning when empty stomachs dictate. The Jap guards themselves fostered the business by the secret purchase of internees jewellery and watches. My own rings, brooches, watch, plus my husband's studs, links and watch were disposed of for this purchase of very necessary food. It goes in the saying that we received a mere fraction of what the things were worth. For instance, half a bottle of peanut oil was bought with the proceeds of a heavy 22 carat topaz ring.

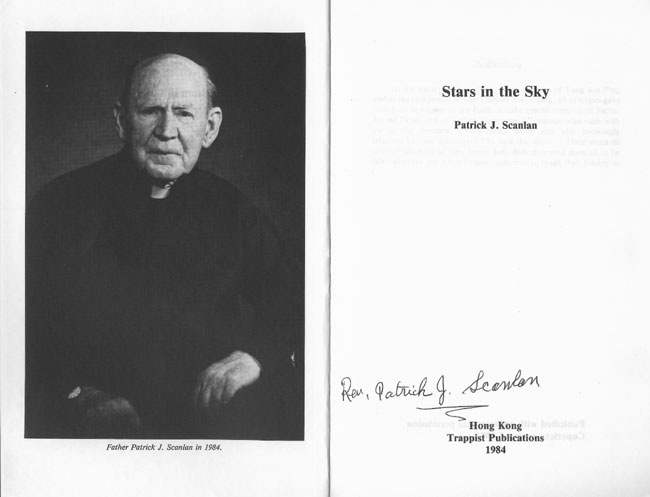

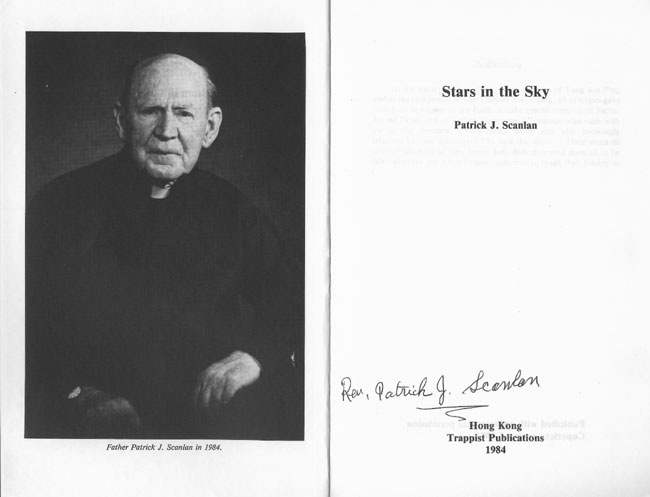

Father Patrick Scanlan

One of our most successful ''merchants'' was a Trappist father. By all accounts he had a special dispensation permitting him to speak, and he surely used his tongue in a great service, especially for the children. He managed to get eggs, rice, sugar, peanut oil, etc, and just charged the bare cost of the goods. Helpers were organised and they guilefully decoyed the guards on "wild goose'' chases with empty baskets while the goods were slipped over the wall at a different spot. It was said that later on the father, whose room abutted the outer wall, had an opening through the wall under his bed, the bricks being replaced when the goods were pushed through. He came under suspicion but managed to evade arrest for a long period but was eventually "gathered in" and was sentenced to two weeks solitary confinement in a cell adjoining the guards' quarters. He arrived back in the camp kitchen five days after his arrest. When questioned concerning his early release he said that he thought the guards didn't like his voice when he chanted during the night! However, he was given a room in the centre of the camp with another priest. The outer wall of the camp was then fitted with wire and electrified. In consequence we all tightened our belts. This was something we couldn't cope with.

Our food supplies were very thin. Small hoards had long since been expended and the bread, less plentiful and of much poorer quality. Yeast was hard to come by and we experimented in growing our own cultures but it was very difficult to get a pure culture and in consequence, the bread was sour and we began to get upset tummies.

Tea we heard was on sale in the canteen and those of us with any cash in reserve, bought some and thereby succumbed to a very mean swindle. It was proved to be nothing more than roasted willow leaves. The brew was a salty, brackish liquid too nauseous for drinking.

After two and a half years of this life we began to feel that it was our lot to go on living this life for ever. And then, we would momentarily free ourselves from the depression and hate ourselves for giving way to an impulse of disloyalty to those who were giving their all in the service of freedom. At times it was terribly hard to cling to our faith, but somehow we did.

The camp abounded in rumour. One story chased another and some, we found later, were, surprisingly, true. At this time there were more rumours than usual and there began a feeling of optimism that somehow one couldn't shake off. We certainly were allowed an English language newspaper, printed in Tientsin, but as it contained nothing more than Japanese and pro-Axis propaganda, it left us cold. It was possible however to dissect the reporting and arrive at some pretty sound deductions that pointed to the opposite direction of the so-called printed views.

It was not revealed until much later that there was a way in which authentic news reached the camp. The messages were sealed in old condensed milk cans and dropped in the open cess-pool by a coolie in the pay of the Nationalist Government. Outgoing messages went the same way. The Japs are usually mortally afraid of infection, and this was the last spot they would dream of hanging around. There were only three men in the secret. It was far too dangerous to let it be known generally. The Japs were always making surprise raids in the hope of finding concealed radio sets. One can readily understand why.

The news of the first landings in Caen were obligingly told us by the Japs themselves. They were enquiring in the camp for maps of the place! As it was a serious offence to possess a map, the response of course was nil, but as they seemed genuinely interested in getting an idea of the location of this place and no "strings" appeared to be attached to the request quite a number of maps saw daylight for the first time for years.

One morning on the way to the sewing room a large plane flew over the camp and I was almost positive it bore American markings. I hurried back to spread the news but found that I was not alone in my discovery and all agreed as to the identity. As we stood there a heavy roar fell on our ears and there, sure enough, was the welcome plane. In a few moments it was joined by another and by this time hundreds of wildly excited internees were gazing skywards. Suddenly from out the planes parachutes descended with what appeared to be packages and men.

The seven magnificent men !

This was the signal for a mad rush of the whole camp out of the main gateway into the countryside. The Japanese guards with their machine guns and rifles were absolutely ignored. Nothing I'm sure could have stemmed that frenzied rush. The Japs bowed to the inevitable and the mad crowds streamed past them and out of the gate that for over two and a half years had been barred against them. This was freedom and we drank it in wild heady gulps.

We raced on through the small village and the less hardy met the returning crowd with our deliverers, an American major, lieutenant and five other ranks. They had volunteered to come to the camp as contact had been broken with us for over ten days and the authorities feared the worst. They were equipped with explosives to blast open the gate if the necessity arose.

Their action in coming as they did, landing in remote, hostile territory with the odds so heavily stacked against them, is an epic in itself. There were forty five well armed Japs and further detachments in the immediate vicinity should they choose to call them and yet those seven men arrived in the camp as cool as cucumbers. They were borne into the camp shoulder high, the Salvation Army leading the show with their band. We choked back our emotions as best we could but a number were openly in tears. It was a day to remember for the rest of our lives.

An American flag miraculously appeared from somewhere and hung from the tower of the compound buildings. It was almost too good to be true.

The Japs, thinking that an American force had arrived by air, retired to their quarters, so the major took possession of their administrative block, had the radio transmitter set up and contacted his base in a matter of minutes.

The camp crowds milled around the main compound, laughing and singing, unwilling to let our visitors out of their sight. The amount of handshaking they had to go through must have been an ordeal in itself. The children clung to them and followed them everywhere so that it was difficult for them to do any work at all.

We were told that planes would arrive the following day bringing food, clothing and other comforts.

I received a message asking me to go to the office where I was asked to collect the sewing room staff to make letters out of white material to read "O.K. to Land." They were to be forty feet long and were intended for the nearby airfield as a guide to incoming planes. They were to be finished by 6 a.m.. the following morning.

There were plenty of volunteers, but of course no material. That difficulty was overcome by using parachute material and some blackout material found in the Jap offices. It hurt us very much having to cut up this nice material, having so few clothes ourselves, but all in a good cause and the work was finished in time to be taken to the airfield in the morning.

Kids on the wall !

The next day was a wonderful one for the children who were allowed to climb on the wall now that the electrified wire had been removed, to watch for the planes. They commenced to arrive about 11 a.m. led by a silver coloured one known as the "Flying Angel." To us, that name seemed so very appropriate. It circled the camp, its silvery wings flashing in the sunlight, then suddenly, out of the bottom dropped a dozen coloured parachutes, each with a container attached. When the last container had landed they were fetched in from the outlying fields and carried into the Assembly Hall to await sorting and distribution of the contents.

One or two of the containers had burst on landing and what a wonderful time the children had collecting treasures. They arrived back in camp with their faces smeared with chocolate and sticky with fruit juice. It was a marvel that they were not ill being without luxuries like this for so long. Chewing gum was the greatest find of all, they revelled in it. A number of children born in camp had never tasted any of these things before.

The committee worked hard arranging the distribution of food and other things to the camp. It was a happy band of people who sat down to their first good meal that day and for many days to come. We were indeed thankful for Uncle Sam' s generosity.

US B-29 bombers & ... food drops.

The following Sunday we had more visitors by air. From Okinawa they radioed that they intended dropping clothing and shoes. They nearly killed us with kindness, the packages dropping all over the camp. One container fell through the kitchen roof, another on the roof of a room, whilst a few landed in the tall trees. We took cover until they had departed but it was a marvellous sight to see the stacks of clothing when all the containers had been emptied. The shoes were a godsend as a number of people had been walking barefoot for months, the children likewise. We dreaded the thought of the cold winter coming without shoes.

American troops had arrived by this time and the Colonel in charge of the force had organized the Jap guards to assist in guarding the camp. It was thought possible that the communist troops in the vicinity might be tempted to use the camp inmates as political hostages in their feud with the Nationalist Government. There were ample grounds for this belief.

In the meantime, the sick in the hospital were evacuated by air and five hundred from the camp sent by train to Tsingtao to await transport to their various destinations. The rest were promised a fortnight for recuperation at Tsingtao before being sent back to Tientsin and Peking.

The night before we were due to leave we held a round of farewell parties. Our beds had been sent off in advance and we found the floor nothing at all to worry about as far as sleeping was concerned, with the prospect of such a tomorrow.

We were up and seated in the trucks which were there to take us to the station, at 4 a.m. Our truck was near the end and it seemed ages before it came for us to start. We were almost in sight of the station when the convoy came to a halt and we wondered what had happened. It wasn't long before we found out. The Colonel arrived and broke the sad news that the communists had blown up a number of railway culverts and a long stretch of the railway line. It was impossible for the train to start. We were disappointed to say the least of it, more so for the children as we talked of the sea, sands and holiday.

It was a very dejected procession that returned to camp. We opened up our room and started again the dull old routine of queueing up for water and food and doing the same deadly chores we had known for three years.

We had been rescued from the Japanese on August 17th, and here we were in the month of October. When would we get free? Our spirits were at low ebb.

About a week later there was a whisper in camp that we were to be flown out. A discreet enquiry and I verified the story.

This time the American Army intended no hitch in their plans. On the 23rd we piled into waiting trucks and drove off to the airfield. One by one the Dakota's touched down on the field, filled up and bore us off to Tientsin..

So ended our interlude.

In retrospect, what had we lost by our experiences and what was our gain? In loss, our personal liberty for three years and all our possessions. In gain, what? We had learned the great lesson of denial and found virtue in the same street. Grew to respect tolerance and realise what it means. Found the pleasure of giving far richer than of receiving. Grew to accept privation and be thankful for small mercies. We are richer by far by our experience, what more is there to say?

***

Hong-Kong harbour in 1920.

Shanghai bund before WWII.

Coastal steamer, the SS Ting Sang

https://industrialhistoryhk.org/the-ting-sang-first-owner-indo-china-steam-navigation-co-ltd/

America at War with Japan !

... very old Radio !

... British armband issued by the Japs !

... British flag over Gordon Hall - Tientsin. !

... Brian and his parents on their way to Weihsien !

... entrance to the Weihsien Compound

... Kitchen #1

Roll Call

The Hospital is the three storey building at the upper right of the photo ! The Jail is just in front and on the left edge is Block-23 with the bell-tower.

The "Church/Assembly Hall" photo taken in 1908 by Erik Gustafson's father ©

m/v Gripsholm arriving in New York - December 1943.

Father Patrick Scanlan

The seven magnificent men !

Kids on the wall !

US B-29 bombers & ... food drops.